Introduction

Head and neck cancer is one of the most common neoplasms in the world and with the highest mortality rates.1 Due to their location, these tumors affect critical swallowing, breathing and communication structures.2 The primary treatment for head and neck cancers includes surgery and/or chemoradiotherapy.1 Surgical resection can be with or without surgical defect reconstruction, and the tracheotomy is used to bypass the extension postoperative upper airway edema that occurs as a result of the surgery.3

Head and neck trauma and cancer are the most frequent indications for performing a tracheotomy.4 The need for tracheotomy comes up to be associated with respiratory failure, neurological disease, spinal cord injury, head and neck tumors, and major surgery.5

Tracheotomy can be defined as “a surgical opening in the trachea” 6 and in terms of localization “the tracheostomy should be made between the 2nd and 4th tracheal rings.” 6

Tracheotomies can be permanent or temporary; we will only address the temporary ones performed in surgery.7 In this case, the tracheotomy is realized, electively, as part of a planned procedure, in a surgical context in the head and neck area.7 As a temporary measure of respiratory support, the tracheotomy will later be removed, according to a medical decision.7 Decannulation is the process of removing the tracheotomy tube that includes the mechanical movement of removing the tube from the tracheal and the process before and after the removal, which includes decisions based on evidence of safe procedure and post-procedure surveillance.

Concerning the criteria and factors that influence the success of safe cannula removal, the presence of swallowing and effective protective coughing are usually minimum requirements for success in this process.8,9

There is a paucity of literature on tracheotomy decannulation process and the nursing role in the interdisciplinary team. This review aims to identify the nursing interventions in the decannulation process in patients undergoing head and neck cancer surgery.

Methods

We did this rapid systematic review to respond to a specific need in a timely manner, allowing the production of evidence with effective management of resources.10

This rapid review was conducted in accordance with the World Health Organization (WHO) Rapid Review Guide11 and followed the reporting guidelines for systematic reviews.12

Using the Participants (head and neck cancer patients), Concept (nursing interventions in the decannulation process) and Context (inpatients) strategy, we present the eligible criteria for this review.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria: Papers were considered eligible if: 1. They included nursing interventions in the decannulation process; 2. Were published in English or Portuguese. 3. The population were adults. Exclusion criteria: articles with nursing intervention in decannulation in patients with neurological pathology because they have very different characteristics from the study population. Publication in book chapters, theses, literature reviews, editorials, or conference abstracts without a full paper were also excluded.

Search Strategy

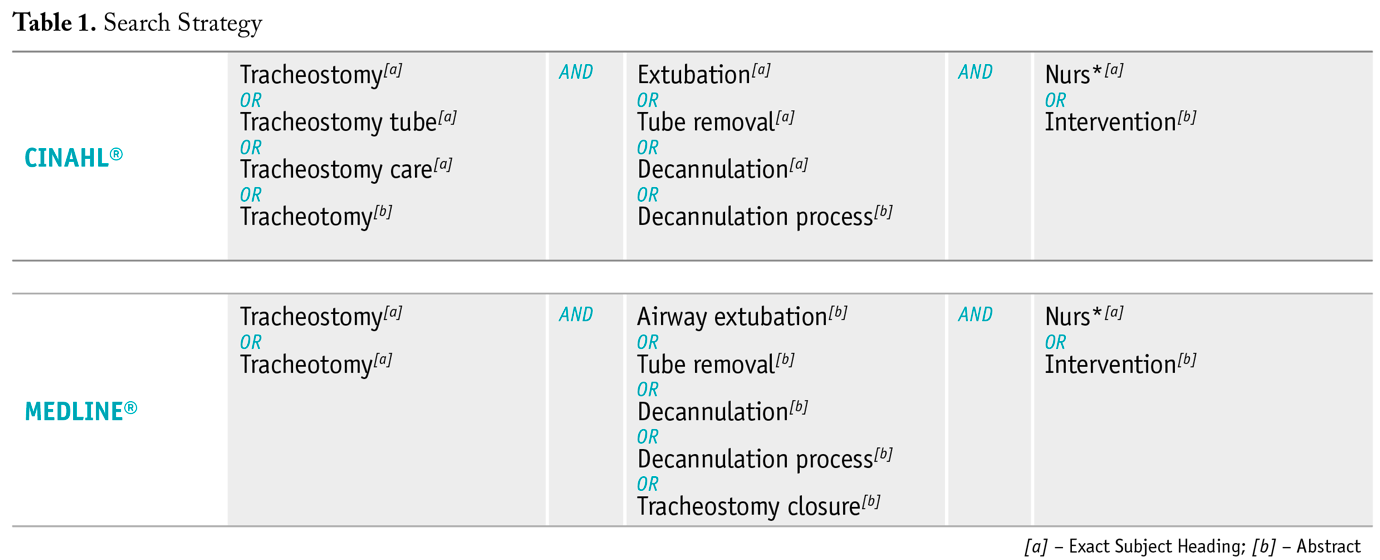

The research was conducted in January 2023. Terms indexed in MEDLINE®, and CINAHL® were used, as shown in Table 1, with the respective Boolean operators. Terms in natural language were also searched in the abstract. When undertaking a rapid review, it is recommended to search a limited number of databases.13

Study selection

The search results were downloaded from databases and uploaded into Rayyan®. Duplicates were removed. Applying the eligibility criteria, with the blind screening of the title and abstracts, was undertaken by two reviewers (AF & SM). The relevance of the articles to be included in the review was analyzed based on the information provided in the title and abstract, and all the conflicts passed to the next step. The full-text screening was undertaken independently by reviewers (AF & SM).

Data extraction and analysis

Data extraction of the included studies was undertaken by one reviewer (SM) and checked by a second review (AF). The researchers designed an instrument in line with the objective of the review. It includes methodology, participants, country, study design and nursing intervention.

Results

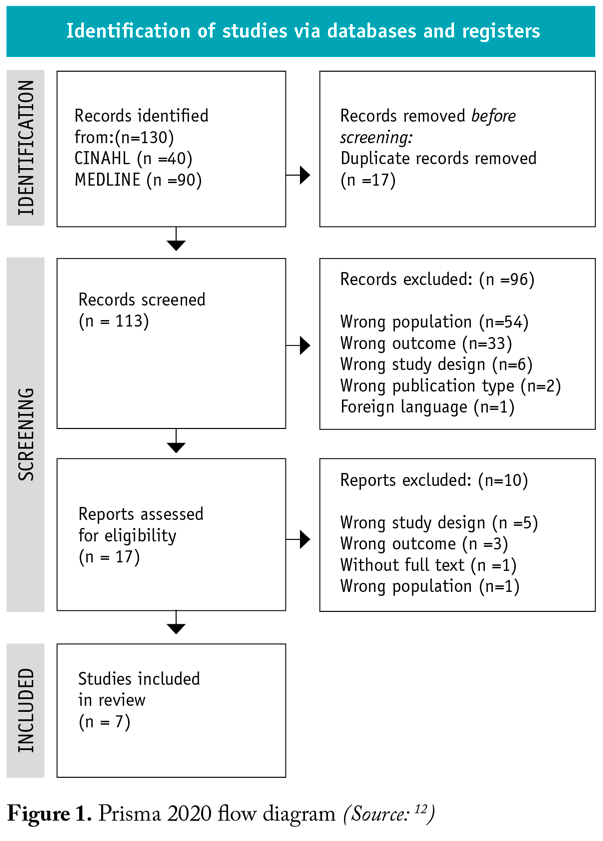

A total of 130 papers were retrieved. When duplicates were removed, the title and abstracts of 113 papers were screened, and 17 full-text papers were assessed for eligibility. Seven papers met the inclusion criteria (Figure 1).

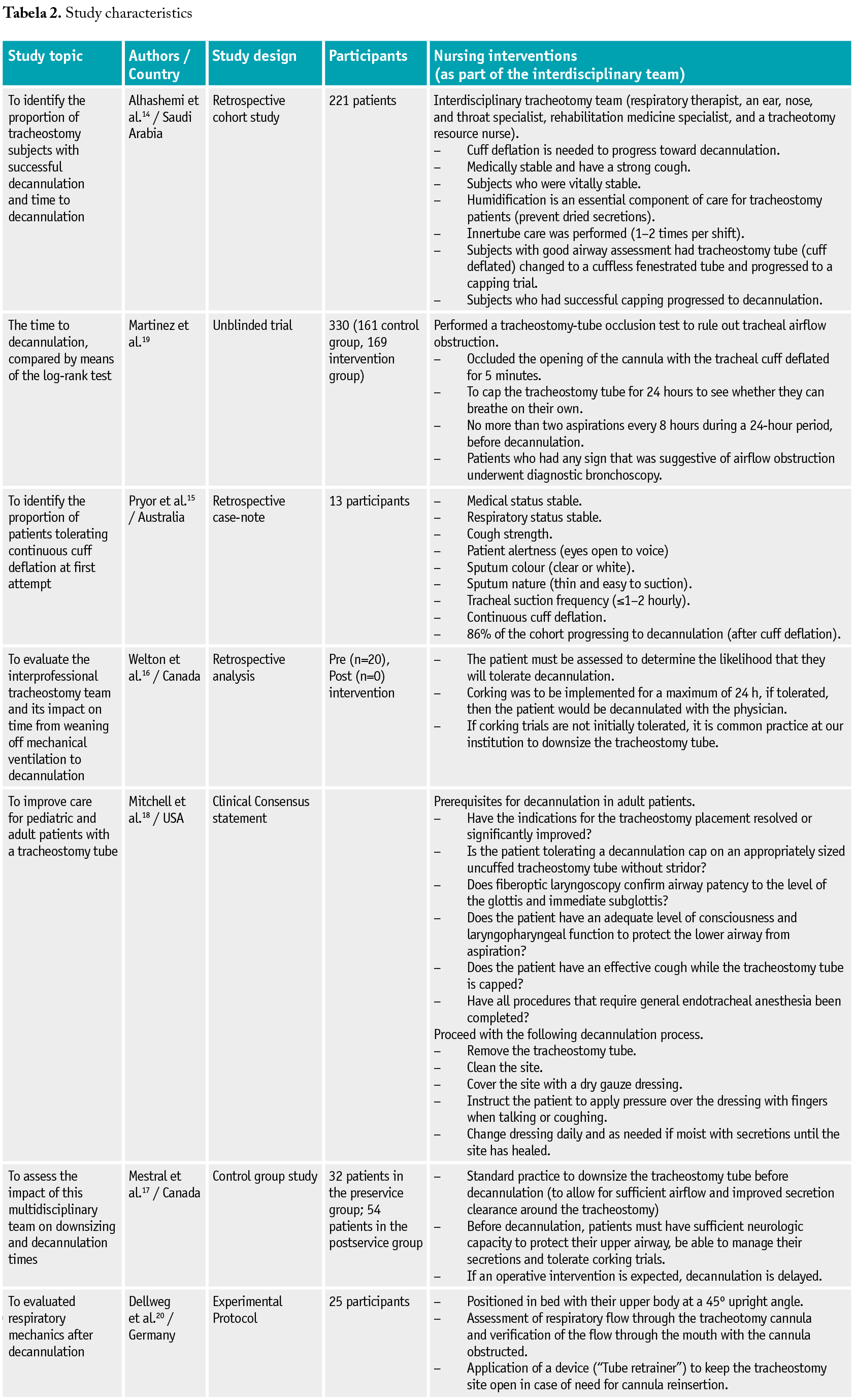

Seven studies were included in the review. The studies were performed in Canada (n=2), Europe (n=2), USA (n=1), Saudi Arabia (n=1) and Australia (n=1). The number of participants in the studies ranged from 20 to 330 (Table 2).

For the analysis of the nursing interventions in the health team, we grouped the interventions found in the review into three groups: 1) before decannulation, 2) during the decannulation process, 3) after decannulation.

1) Before decannulation

Before starting the decannulation process, the leading cause for the tracheotomy must be solved, and clinical stability or normality of vitals observation was a prerequisite.14-17 Understanding whether the patient will soon need any anesthetic or surgical procedure.17,18 In this case, decannulation is delayed.17

Assess that the patient can protect his airway with a strong cough14,15,18and no more than two aspirations every 8 hours during 24 hours before the decannulation.19

It is consensual that cuff deflation is needed to progress toward decannulation.14-16,18 At this time is suggested to change for a tracheotomy tube without the cuff and fenestrated tube. Assess respiratory flow through the tracheotomy cannula and verify the flow through the mouth with an obstructed cannula.20 That change is safer if using a device application (“Tube retrainer”) to keep the tracheotomy site open in case of the need to reinsert the cannula.20

The next step will be to cap the tube trial for a maximum of 24 hours; if tolerated, the patient should be decannulated;14,15,18,19if this process fails, some authors suggested downsizing the tracheotomy tube.15-19 The physician stopped the trial cap if the patient had any sign of respiratory distress.19

2) During the decannulation process

The decannulation process should be done by an experienced physician and nurse.16,18

3) After decannulation process

After decannulation, the patients should be monitored for decannulation failure.18 It is advisable to position the patient in bed with their upper body at a 45° upright angle.20

After removing the tube, cover the stoma with a gauze dressing, change daily and as needed if moist with secretions until the site has healed18, and keep the stoma clean.18 After decannulation, patients should be instructed to apply pressure over the dressing with their fingers when talking or coughing to decrease the air leak.18 The nurse identifies the subjects’ needs, like training, material and equipment, and caregiver education.14

Discussion

From the review, a multidisciplinary team with a consistent and systematic approach to these patients emerges as a success factor in the safe decannulation process.14,17,18In the search carried out by Escudero and collaborators, they state that the decision to remove the tracheotomy tube is a multi-professional process.21

Before starting the decannulation process, first, it must be resolved the primary reason for the elective tracheotomy.21 New surgical interventions should not be planned involving general anesthesia.22

During the process of decannulation ought to be present the health team, able to reinsert the tracheotomy tube in a post-decannulation emergency during and following the decannulation.7

Reducing time to decannulation would be expected to reduce the risk of developing hospital-acquired pneumonia,23 early removal also improves patient satisfaction and allow a more rapid post operative recovery in patients undergoing surgery for head and neck cancer. 23

Decannulation should be performed before ten days, particularly for patients with head and neck cancer with free flaps, avoiding the risk of prolonged or permanent tracheotomy.3,23 Patients with total glossectomy defects and those who continue to smoke during the perioperative time are at increased risk of delayed or failed decannulation.3 Education programs for smoking cessation should be performed during the preoperative time. Patients who smoke beyond the 4-week preoperative time have 35 times more risk of failure decannulation and take more time to decannulation.3 Thus, decannulation should be carried out as early as possible after resolving the issues that were the basis for the need for tracheotomy. The presence of a tracheotomy makes patients more susceptible to respiratory tract infections, particularly if they have a cannula with an inflated cuff.7

This review also identified the care once the decannulation. After removing the tracheotomy tube, nurses should care for the stoma by cleaning it with 0.9% sodium chloride, drying it, and then applying an occlusive dressing according to the institutional guidelines.7 This dressing should be changed every day, and the site observed for signs of infection.7 Nurses need to teach the patient to press on the dressing directly to the stoma when talking or coughing to occlude the stoma, reducing the air passed through the stoma, enabling the patient to have a better voice and helping the stoma to heal.7

For the patient, removing the tracheotomy tube restores a sense of physical and psychological normality.7However, when starting the decannulation process, people may become anxious and worried about not being able to breathe without the cannula.7 Therefore, professionals need to discuss each step of the decannulation process with the patient and any fears or concerns they have.7

Limitations

This rapid review has a few limitations. Only papers in English were included. We couldn’t find the full text of one article. Nursing interventions in the decannulation process of head and neck patients do not allow generalizations to be made to other populations. It would be interesting in future studies to compare different types of patients.

Conclusion

Tracheotomy is commonly performed after major surgery for head and neck cancers. Usually, during the postoperative period, the patient is decannulated. A multidisciplinary approach to tracheotomy decannulation should be performed to ensure safe and appropriate practices.

Decannulation should only be undertaken when the patient has completed all the steps toward decannulation. The management of the process of decannulation should have a plan for a systematic approach to tracheotomy progression. In the future, it would be interesting to identify studies that compare the decannulation process between men and women, as women are generally tracheotomized with smaller-diameter cannulas.

Tracheotomy progression is essential in daily assessment and planning and improves the quality of life of the head and neck cancer patients undergoing surgery and their families. In this decannulation process, nurses can motivate and encourage, assess respiratory well-being, and ensure that training and material education are met and attended, assuming a privileged position next to the patient.

This review presents the nursing team's importance in all decannulation phases. It reflects the relevant role in evaluating the conditions and the other team members in the preparation, procedure and post-decannulation monitoring, preventing decannulation complications, such as the need to cannulate the patient again.

The review intends to guide the practice of the Nursing team when dealing with a patient with a tracheotomy with planned decannulation, favoring earlier and safer decannulation, increasing the safety of the professional and also of the procedure and contributing to the safety and well-being of the patient.

This rapid review highlights the need for a structured and systematized program for the patient's decannulation process, which will ensure the safe and effective management of patients with a tracheotomy. Nurses have an active role in all phases of the decannulation process.