1. Introduction

The insights presented in this paper are based on the case study "Tango-Down Athena. Theatre and Design as hacking means of the contemporary urban myth", a research project - funded by Compagnia di San Paolo Foundation (Italy) and developed in collaboration with CRAFT, a theatre research and training centre - ran by the Polimi DESIS Lab of Politecnico di Milano for the city of Ivrea (Italy) in 2019/2021.

This paper articulates on how this situated project served the authors to explore an undeniable feature of design: namely, its ability of making futures through speculation, fiction, critical reflections, and probing discourses. From the situated context of Ivrea - that functioned as a pivotal case - the authors explore here the possibility to draw some fresh theoretical reflections on envisioning futures through citizens engagement in fictional role play.

1.1. The context of the research

In 2018, the city of Ivrea has been listed by the UNESCO World Heritage as an exemplary of progressive modernism and an "Industrial City of the 20th century" for its industrial past, founded and developed by the Olivetti Typewriter corporation, that assumed responsibility for ‘urban and territorial planning’ as well as industrial production. This has been mainly influenced by Adriano Olivetti’s physical and ideological presence, who, despite its relevance for the cultural life of the city, had the pitfall to create a mythological and unified narrative about the city. The latter remained also after the exhaustion of the industrial production of Olivetti, generating nostalgia and a sense of lack of new narratives. The industrial area of Ivrea, developed between 1930/60 thanks to Olivetti, proposed an alternative model to the 20th century national and international similar experiences of industrialization in urban contexts. As a matter of fact, the company took on the responsibility for the urban and territorial planning, not only by looking at the production environment but also at its social and cultural programme. This area counts buildings for production as well as for social purposes (such as a canteen and a workers’ recreational club), services for citizens (nursery schools, day-care, paediatric services, after-school programmes, summer colonies, training schools and various cultural, sporting, and recreational activities) and residential units (for large and single-family and also small houses). This means that the company’s development had a huge impact on the entire urban structure, making the city and the surrounding area a lab for experimentation of spatial, cultural, and social projects and ideas.

The plurality of forms and languages showcased by these architectural artefacts shows how much Ivrea’s heritage has represented throughout the past decades an inspiring example for other coeval industrial cities, with a plethora of solutions elaborated by the 20th century design culture to respond to some of the key questions raised by the growth of cities invested by industrialization processes.

The death of Olivetti in 1960 marked yet a break in the city’s history. The change in the factory's leadership led to a consequent change of vision, causing in the ‘90s a fragmentation of the architectural heritage and, finally, leading to the current situation, where the industrial production has eventually ended. Consequently, many areas are currently abandoned or underexploited, while some institutions - such as the Olivetti Historical Archive - are trying to preserve the historical and cultural heritage of Olivetti’s vision. While there have been in the past decennia some brave attempts to give new life to the area (cf. the Interaction Design Institute, an advanced design school promoted by Telecom in collaboration with Stanford University, closed in 2005), those initiatives had never been able to provide a new vision and to bring some real social and cultural change.

Considering the difficulties so far in further developing the city, the fact that the latter has been recently UNESCO appointment as a World Heritage site can represent a potential for finally succeeding in powering a future functional regeneration which could boost Ivrea as an innovative technological and cultural pivotal point (as it used to be in the past century), creating new narratives and addressing new visions, thus further enriching its now fragmentary identity. As a matter of fact, there is a macro narrative about the Olivetti’s (the father, Camillo, and his son, Adriano) as creators of a lost golden age. This rich past has generated a well-recognized urban myth linked to their role, that has split the citizens of Ivrea in two groups of people. If, on the one hand, this sense of return to what it was is constantly re-proposed by the city as a unique and irreplaceable narrative, on the other hand the latter feels somehow uncomfortable for those people willing to move on into a future of possibilities (not yet necessarily connected with Olivetti's past). The diverse social and cultural developments in the neighbourhoods have accentuated these differences even more, steering the identities of the local communities in multiple timeframes and directions, and creating some polarization, often based on (mis)perceptions and prejudices. Besides the area linked to the industrial heritage, and thus heavily connected to Olivetti’s myth, and the historical centre with its medieval traditions, the neighbouring areas are currently becoming more and more relevant within the economy of the city and ended up becoming a landmark of the city’s educational and infrastructural system in the past decennia. Some thriving local communities have been able to go beyond this nostalgia of a golden past and to refresh the city’s identity by means of bottom-up actions linked for instance to cultural initiatives, sporting activities and the development of a now well-known music label. Throughout the years, these local communities have generated micro narratives providing new identities to the city. This transformative process had yet a pitfall, as those renewed identities often ended up causing new polarizations, resulting in latent conflicts and difficulties of mutual recognition. As a result of this process, while one side of the city is still stuck in the past, other neighbourhoods are projected towards alternative visions, which are yet often still weak and eventually unable to provide the transformation needed on a larger urban scale.

1.2. The purpose of the research

The goal of this research project is to address this social fragmentation and unpack its narrative to open social imagination and question the current underlying (and often unexpressed) local controversies to collectively envision possible futures. The participatory envisioning of possible futures has served here to engage diverse voices in conversation and create a common ground for a more participated and inclusive social transformation. The need to question the past urban myth and to create a conversation with the city’s diverse voices and souls has represented for us the starting point for co-creating with these diverse local actors coming from different neighbourhoods, and for powering different kinds of narratives as potential future narrations which could serve as counter-narratives, questioning their points of views, bringing those contesting voices in dialogue and possibly creating amongst them stronger social bonds (which are the actual requirements for real social change).

The research team addressed therefore an idea of participation going beyond the tangibility of the impact of solutions for a society-driven innovation, and rather aims to identify and question diverse underlying points of view, possibly articulating a dialogue between those contextual voices by gathering them around present and future possible common matters of concern. The Ivrea case study served to explore how Future Studies, Anticipation and Future Narration perspectives could be integrated in design, experimenting through PD activities how to collaboratively envision potential futures. By envisioning alternative future behaviours, the research team explored how to tackle complex relational social issues and reframe them, opening the social imagination to envision together through design fiction what the city could look like in the next future.

In detail, the research team generated and tested a civic game meant as a tool to co-create future scenarios by imagining alternative pasts and presents for the city of Ivrea. In the making of this civic game, PD processes have been hybridised with storytelling and design fiction. This resulted for instance in touchpoints such as cards and props, meant to stimulate a collective narration among citizens and their envisioning capacity, and to provide a solid basis to address the research insights.

2. Problem

2.1. Research questions

The outlined context confronted us with the opportunity to experiment forefront methodologies with a cross-disciplinary approach: how to set-up an engaging process with citizens by means of PD actions to conduct a participatory foresight process to co-articulate meaningful directions for their own territory and co-envision future scenarios? How to reframe shared values for a city by creating a conversation among unidirectional voices? How to use storytelling to generate shared narratives through a fictional role play?

2.2. Main theoretical concepts

Design - as the practice of making futures in everyday practices (Tonkinwise, 2015a) - and fiction for civic sense-making have been outlined as a relevant area of exploration for the pivotal role they can play in PD (Czarniawska, 2004; DiSalvo, 2009; Wittmayer et al., 2015). This approach stands on the notion of provocation through concrete experiences of prototyping, also known as “provotyping approach” (Mogensen, 1992). Since prototyping, as a process directed towards the construction of desirable future, serves not only to trigger discussions about the future but also on current practices (Mogensen & Trigg, 1992) and modes of relation, it can then also mean to develop metaphors and imaginations to turn current issues into constructive means towards possible futures. “The idea from prototyping is to provoke by actually trying out the situations in which these problems emerge: provoking through concrete experience” (1992, p. 39): provotyping. Far from the aim of pursuing viability and sustainability of innovative advances through “user-oriented innovation” (linked to the evolution of computing and communication technologies and of management innovation theories, cf. von Hippel, Chesbrough) or “transformative innovation” (linked to the sociotechnical transitions; cf. Steward), this situated context of research called for a more philosophical and sociological reflection on co-created narrative processes, using a collective role-play to negotiate interpretations of the reality and possibly reframe them.

2.3. The approach

Building on this approach, we developed a dynamic interplay where PD activities with citizens, generated to collect data and to stimulate active engagement, have been turned into an interactive role game to collectively reflect on Ivrea’s public spaces, merging the personal and shared memories of the citizens towards agonistic conversations. This interplay touched upon the constitutive politics of the social dimension (Mouffe, 2007), and in detail to the widely explored - particularly in PD - relationship between design and agonism (Mouffe, 2000; DiSalvo, 2010; DiSalvo et al., 2011; Hillgren et al., 2016; Koskinen, 2016). This cross-disciplinary process required to open the research team understanding of PD activities in terms of key methodological approaches, researching how a PD co-creative process can inform a storytelling process. The exploration of a possible cooperation between disciplines - especially in multi-faceted milieus - requires a transition from an approach based on disciplines to one based on strategic planning. This means that design to cross borders in order to design systems, strategies, and experiences rather than objects, visuals, or spaces.

2.4. Propositions:

This experimental approach in design, where PD has served as the basis for the co-creation of future narratives, has been crucial for us, as the project’s goal is not that to directly co-design new initiatives in the neighbourhood, but rather to investigate diverse levels of engagement and tackle the contextual complexity, identifying controversies and opposed perspectives and conducting within this given situated context a social conversation towards a non-solutionism(-based) (Manzini, 2016) process. This requires an in-depth understanding of the role of PD activities not so much for making alternative future but for envisioning them while shaping a better present. As a matter of fact, PD and design for social innovation practices are not only necessarily meant to empower communities towards efficient, durable, scalable, and replicable solutions but also towards questioning/re-framing the public realm, possibly triggering the participation of citizens and other local stakeholders such as local associations, administrators, policy makers, etc. in the democratic debate concerning the public realm and current social issues. In this specific case, the character of the expected design outcome was not aimed at traditional tangible outcomes such as for instance co-designed spatial solutions tackling territorial identity issues or strategic solutions to undertake future models, but rather to detect hidden potentialities and materializing futures by co-developing alternative narratives. The nature of this design outcome has been particularly puzzling for our research group, as it confronted us both with the questionability of the effective agency of the project’s design innovation as well as with the difficulties connected to such an open ended, ephemeral outcome, which makes it particularly difficult to assess the project’s expectations in terms of tangibility, particularly in the short-medium run.

3. Methodology

As previously described, the project is situated in a specific context characterized by a series of pluralities and divergences played out throughout time. For this reason, it has been necessary not to start with a particular theoretical framework, but to gather data from a variety of grounded sources. Therefore, in trying to weave the different visions and the structural relations among actors in their social environment, a qualitative approach based on Grounded Theory has been at first developed for the data collection process. A Grounded Theory methodology, in fact, calls for the use of various and cross-disciplinary research techniques also to go beyond clear and definite theories and meet the transdisciplinary research need of exploring new ideas and develop new techniques.

Starting from the desk research, our team analysed documents related to the candidacy process such as conference proceedings and other reports related to Ivrea as UNESCO site. Thanks to a series of interviews with local experts, policy makers and academic researchers involved, the team has been able to better frame the diverse communities of Ivrea, identifying for instance community “leaders” and spokespersons, to then organise informal conversations with them. By joining and directly observing community meetings discussing the transformation required by the UNESCO label, we started to establish a relationship with the community. Secondly, we started to enlarge these local networks by setting up informal conversations with other citizens, associations, and retailers.

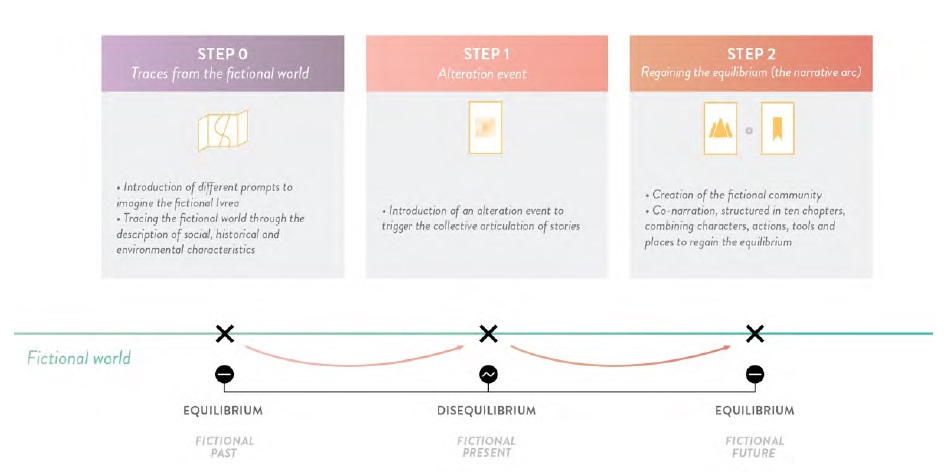

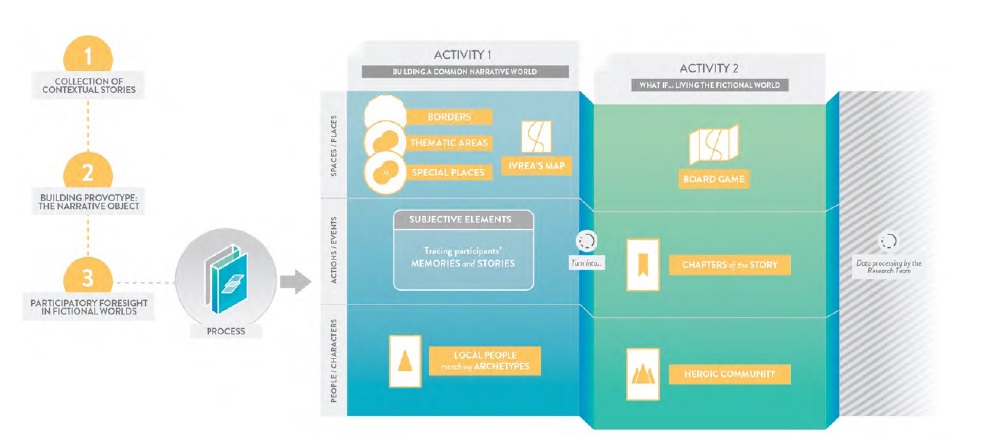

This data gathering served to better understand the inhabitants’ cultural linkage to the city, its specific historical evolution and the citizens’ memories and stories. To better articulate this process and envision its scope and strategies, we used a ‘blue-sky’ research to define its conditions and its context. This process revealed a rich heritage of extremely interesting "oral stories" which helped us to define the foundations for the creation of the PD main activity conducted with citizens (i.e., the civic game). The data collected served us to build a situated Foresight Process (Voros, 2003) in order to develop explorative outputs (the narrative object) intended as input into the final Participatory Foresight activity (Dunne & Raby, 2013; Heidingsfelder et al., 2015; Huybrechts et al., 2016; Voros, 2003) developed with the local actors. Below the three different key steps (Fig. 1) which shaped the designed participatory process are summarized:

3.1. Grounded Theory Research: collection of contextual stories

To approach such a complex and both culturally and historically overloaded context, it has been necessary to carry out a series of different steps. During the first phase, in which the context has been framed, the team took the time to be immersed in the context, getting in touch with places and communities, while collecting data about both Ivrea’s past and present by means of desk research and experts’ interviews. This served to develop a network with internal and external communities, and to get to an unambiguous understanding of the contexts’ complexity. What emerged from this first phase is a much more diversified context than previously expected, rich in conflicting opinions and historical-cultural divergences. The latter urged us to ignite a PD activity with the aim of articulating agonistic conversations (Arendt, 2013; Mouffe, 2000, 2007) among citizens. The activation of this path of democratic sharing of ideas felt to us as pivotal to highlight and bring to light the potentials of citizens to proactively and collaboratively act and possibly achieve a common goal.

3.2. Provotyping visions: building the narrative object

To articulate this proactive debate, the team decided to frame a Foresight Process using storytelling as a tool with a high transformative power to generate processes of change (Tassinari et al., 2017) in Ivrea’s social fabric. The divergences traced in the previous phase and the sensitivity of citizens towards some of those issues, urged us to deal with those with much attention and to look for new ways to make complex and sensitive matters more “speakable” thanks to the use of fictive narratives, in which those issues could be playfully symbolized. In order not to undermine those issues and, at the same time, to stimulate the agonism of citizens on concrete and divergent facts, the current situation has been shifted towards an abstract and symbolic level, where the same issues could assume a more playful tone thanks to the use of Design Fiction (considered as a “provotyping” method). Starting from the need to activate a proactive dialogue and increase the citizens’ awareness, contextual places, people, and problems have been translated into a parallel fictional world, identified by paradoxical collapsing events conditioned by a series of possible future challenges (Fig. 2). This served us to reinterpret what is familiar (real) through a process of abstraction (through the lenses of fiction) for returning at the end to the discovered meanings and understandings of their own resources into a new familiarity (Kemmis & Mctaggart, 2005). The civic game that has been designed in this second phase of PD process ought then to be considered a tool for co-creating counter-narratives (Hillgren et al., 2016, 2020) to the current polarising narratives. Furthermore and within the activity planning, the designed fictions have been enriched by recurring to some narratological tropes (Propp et al., 1966). Looking into narratology, the team found out that stories have a huge potential to convey concepts and information thanks to the use of archetypes, thus of cultural forms of the collective unconscious (Jung, 2014). In this phase, all the previously collected stories have been unpacked, reinterpreted, and expanded to define a set of story-making tools to be given to citizens through a community co-narrative playground, where people, actions and places have here become characters, events and scenes.

3.3. Collectively playing reality interpretations: participatory foresight in fictional worlds

The co-narrative activity developed thanks to designed civic game involved 20/25 people organised in four heterogeneous teams: members of local associations and informal groups, experts in the cultural sector, researchers involved in the UNESCO candidacy process and other citizens from the neighbouring areas of Ivrea. The participants were invited to follow up the PD foresight activity - in other words, the playing of the game - starting by sharing personal stories related to the city context and ending up with the co-creation of a story to tackle a fictitious problem in a parallel world made of co-defined places linked to personal memories in the fictional Ivrea. The complexity of the theme stimulated them to articulate two different activities carried out in sequence (Fig.3), representing the two different steps in the game:

Activity 1 “Building a common narrative world”: definition of a shared vision of the city - physical and conceptual - starting from the stories of the participants' subjective and objective memories.

Activity 2 "What if ... - Living the fictional world": co-creation of possible future scenarios through the creation of a story in the context of an imaginary Ivrea, in which the participants’ current points of views are “abstracted” into another level in terms of temporal and spatial dimensions through narrative elements. This abstraction process has been triggered by the introduction of an element of disequilibrium (hacking) generating an imbalance. The story, created by the interviewees, has been used the narrative world of Activity 1 (cf. the full description of the design process development in: De Rosa et al., 2021).

4. Results

The description of the results here follows the methodological process to underline findings and insights coming from the applied approach.

The Grounded Theory Research phase led us to identify what we could define overlapping geographies: in fact, the exchange with local citizens and the delineation of a socio-identity map of the context, revealed the presence of a series of conceptual areas (physical and mental) in continuous overlapping which had the potential to define the city’s different identities of conflicting connections to the city’s heritage, memories, and identities. The concept of overlapping geographies has been conceptually conceived in the meaning of elements of territorial diversity, or physical portions of the city linked to social, cultural, and human identities which manifested over time and that the research team contextualised into a spatial concept. The term "geographies" represents here a well-defined assemblage of places, cultures, identities, and communities of people. By adding the adjective "overlapping", we mean to give the visual and conceptual idea of both synergistic and conflicting relationships, developed over time within the same territory (Fig. 4).

The design of a narrative object based on a counter-narration has been fundamental to make the interaction with the citizens possible. The highlighted overlapping geographies pointed to the need to strongly ground the participants imagination in their own everyday framework whilst moving real issues into a fictional level: “Grounding imagination is an approach that seeks to work with rather than against the challenge of meeting contradictory demands on shifting ground” (Büscher et al., 2004). In this case, demands not aimed to set a “transformative innovation” meant to boost functional innovations as such, but also to encourage the current bottom-up community of voices which are still unable to engage the city towards a new flourishing phase.

As already mentioned, the project served to contextualise new ideas and develop new techniques: in detail, how to materialize futures by co-developing fictional stories, remaining in the fuzzy front-end of the design process (Sanders, 2005; Stratos Innovation Group, 2016). Through the PD foresight process of designing fictional worlds, the collective role-play enabled the participants to imagine themselves as having the characteristics of the assigned fictional characters (which might be, for instance, citizens with ideas and narratives conflicting with their own ones) and develop a team strategy to overcome the paradoxical events provided, defined as alteration events. These lasts have been pivotal in the design of the narrative object to trigger the collective articulation of stories: through Design Fiction, the team introduced future challenges related to issues arising from indirect actions of non-human agents considered as alteration events. As the concept of overlapping geographies points to the fact that the detected local controversies - made up of conflicting meanings given to places, memories, heritages and cultural identities developed throughout time - were actually too complex to be literally included into the narrative object, we actually decided to address them anyway yet in a more abstract, symbolic way by the introducing black swans (Taleb, 2007), also called wildcards (Voros, 2003): in other words, low probability events that, when occurring, can have high systemic impacts, and thus are apt to shift the participants’ attention towards a fictional level. As “Design Fictions are more visceral and emotive […], quotidian [and] concern the surface experience of a future normal” (Tonkinwise, 2015b), the team used here its ability to generate a detournement and displacement (in place and time) in those interacting with them. Those alteration events (river flooding, desertification, migration due to global warming, etc.) introduced as wildcards in the co-narrative activity provided therefore the initial spark to gather the participants in the co-creation of the fictional story. Thanks to their fictional characters, the participants had the possibility to imagine strategies to counter these black swans by finding alternative ways to coexist with the alteration triggered, without yet restoring the original situation. Those alteration events, that were initially perceived as hackers of the equilibrium, turned then to be considered as actual entities to be taken into consideration to imagine "new forms of relational agencies" (Jain, 2020). This enactment has been the core value of the explorative case and helped to critically evaluate future abilities of the team of “being a community” within utopian - as well as dystopian - futures.

5. Conclusions

The whole design process questions the effectiveness of Design Fiction in PD activities employed in the early front-end of design processes. Furthermore, this case has represented for the team the entry point to better understand the Ivrea context and its internal dynamics, possibly getting in touch with its human heritage, and to enter in dialogue with the local community, enabling also the latter to start the process of disarticulation of polarized narratives (a process which is necessary in order to enter in a phase of engagement with transformative and inclusive urban transformation, and the co-creation of new participated visions for the city). The hope is of course that this process will generate the precondition of new social change and the entering of a new phase for the city: opportunity that will be further explored by the local actors in the context of the UNESCO recognition for the city, and which currently goes beyond the scope and the reach of the project. The divergent viewpoints emerging throughout the research process stimulated the research group to use Design Fiction as a method to abstract participants from the current contextual situation. While co-narrative activity has proved to be effective in stimulating a potential social change fuelled by the co-creation of alternative narratives, the conscious pitfall of this project stands its open character and the consequent difficulty to monitor scope of creating a conversation between unidirectional voices. Standing in the fuzzy front-end of the path, proved that incremental and open-ended PD processes of envisioning through fictional activity can lead to the (re)articulation of civic sense-making, yet if only starting with ephemeral outcomes. What also emerged is that a longer temporal commitment is needed to actually start building shared new visions, and to capitalize on this process of disarticulation of polarizing narratives, that can lead to the generation of new, more inclusive and transversal publics.

The lack of dialogue and proactivity between the local actors ought to be considered pivotal for employing Design Fiction as an entry point to start stimulating a future process of change and innovation. To achieve the effective generation of alternative realities it is therefore necessary to envisage long-term experimental actions - staying in the same context - to trigger infrastructuring processes and make scenario envisioning possible. In order keep on experimentation on this approach to PD, the Polimi DESIS Lab is currently testing this methodology in a neighbourhood of the city of Milan (Italy), where the engagement process started in 2017 thanks to diverse sessions of envisioning activities. Being a long-term project, this Milanese ongoing experimentation is therefore providing a more suitable context for this kind of open-ended approach. Unlike the Ivrea context, the Milanese one lays on a stronger social fabric supported by a proactive community built over a recent bottom-up process of neighbourhood re-appropriation, which makes this case more apt to adopt the design inputs and transform them into exploitable scenarios. Testing different situated design tools and approaches throughout a wider timeframe will be pivotal to design for Milan another fictional PD activity rooted in the community, helping the research team to create a co-narrative activity and to design diverse PD activities to support those visions in the transition towards participated transformative actions.

Acknowledgements

The research project, titled "Tango-Down Athena. Theatre and Design as hacking means of the contemporary urban myth", presented in this exploratory paper, has been funded by Compagnia di San Paolo Foundation (Italy) in 2019 through the call “Ora! - Produzione di cultura contemporanea”. The project has been coordinated the Polimi DESIS Lab (www.desis.polimi.it) of the Department of Design of Politecnico di Milano (Italy), in partnership with “Associazione CRAFT” (www.associazionecraft.org), a theatre research and training centre. The project has been supported by Piemonte dal Vivo Foundation (Italy), I Teatri Foundation (Italy), Cité du Design de Saint-Etienne (France), Tongji University - College of Design and Innovation (Shanghai - China), DESIS Network - Design for Social Innovation and Sustainability (https://www.desisnetwork.org).

The authors are grateful to Patrizia Bonifazio, Scientific coordinator of the UNESCO application for the city of Ivrea, for her generous support and orientation throughout the research project development, and to Lucia Panzieri of “ZAC (Zone attive di cittadinanza)” association for her great engagement in the city and for hosting and helping us for the organisation of the activities that the authors run with the local communities.