Introduction

Asthma is one of the most frequent chronic conditions in the pediatric population, with a high social impact. It is responsible for substantial morbimortality, hospitalization and school/work absences.1-3 Recurrent wheezing and asthma are among the most common causes of pediatric emergency room department visits.2 In the United States, up to 20% of asthmatic children require emergency department visits annually.4 A large multicenter study revealed that asthma was the most common diagnosis of recurrent visitors and high frequency users (more than 4 visits per year) of the pediatric emergency department.5

Inhaler misuse by children and caregivers is an important factor for uncontrolled disease, thus technique review during medical appointments is of crucial importance.6 Since its introduction by 1960, it is known that inadequate inhaler technique results in suboptimal drug delivery to the lungs and, therefore, diminished drug response and clinical improvement.1,2,7 Less than 50% of children benefit from their inhaler therapy.2 Some studies report a high technique error rate even among physicians.2,3 Resnick revealed that only 26% of physicians perfectly demonstrated metered-dose inhalers (MDI) technique.8 They also showed that evaluation and demonstration of MDI technique at one medical appointment was insufficient to optimize patients’ performance.2,9 Technique demonstration by a qualified person, especially when repeatedly, seemed to be an important strategy for inhaler use improvement.10 The national clinical guideline for the management of asthma in Portugal recommends inhaler technique review at each appointment (Evidence A).11

The aim of this study was to understand if repeated demonstration of the inhaler technique to patients and caregivers by an assistant physician improves patients` compliance and reduces error rate. As secondary outcomes, we analyzed the influence of sociodemographic data on error rate. Questions about mouthwash after corticosteroid inhalation and spacer care were also addressed.

Material and Methods

We conducted a prospective interventional study on MDI plus spacer technique between 2013 and 2019, in a tertiary Hospital. One hundred MDI users were enrolled opportunistically as they attended medical appointments. The inclusion criteria were: being a frequent user of inhaled medications with spacer and bringing their inhaler device and spacer to the medical appointment. Patients with only one visit were excluded.

Caregivers were asked to demonstrate inhaler technique during three sequential visits (V1, V2 and V3). Periodicity of medical visits, according to symptom severity and control, was not changed.

Seven variables were analyzed and registered by the assistant physician as “yes” or “no” (Appendix 1) according to patient/caregiver performance (question 1 - Q1 to question 7 - Q7). Two additional questions about spacer care were addressed (question 8 - Q8 and 9 - Q9). Sociodemographic (parental age, education and marital status), disease (clinical diagnosis, familial and personal antecedents) and therapeutic (control and quick-relief medication) data were also collected on V1. The inhaler technique evaluation and the filling out the form was performed always by them same assistant physician.

Analysis was performed with Statistical Product and Service Solutions (SPSS 20.0.0) and R Statistics Software. We compared the total error number in Q1-Q7 during three sequential visits (V1-V3) and analyzed the influence of sociodemographic data on the variability of the obtained results. Fisher exact and Mann-Whitney tests were used to study the correlation between categorical variables and continuous variables, respectively. To analyze the role of inhaler technique demonstration on error rate over time, Fisher exact test was applied. We considered p-values < 0.05 to be significant.

RECORD checklist12) was verified during manuscript elaboration.13)

The study was approved by the Hospital Ethics Committee. Caregiver informed consent was obtained, and patient information was kept confidential.

Results

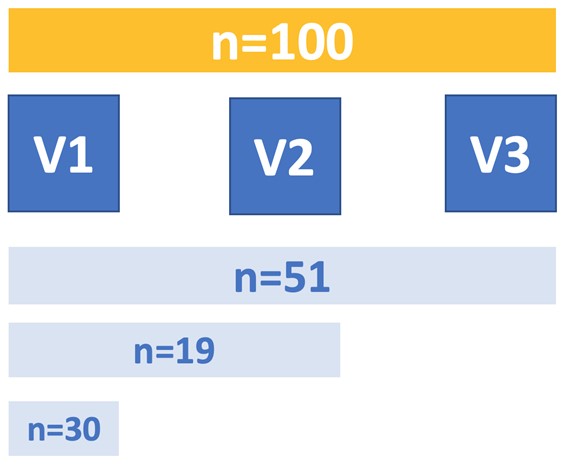

During the six-year study period, 100 patients were enrolled but only 51 were observed three times. Thirty patients were excluded since they had only one observation, so the impact of technique demonstration on error rate could not be analyzed (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Distribution of the patients observed along the three sequential visits - One hundred patients were asked to demonstrate inhaler technique in sequential visits (51 patients demonstrated three times and 19 twice). Thirty patients were excluded from final analysis because they had only one observation.

Patient sociodemographic, clinical and therapeutic data are listed in Table 1. The error rate of inhaler technique, mouthwash and spacer care over successive medical visits is shown in Table 2.

Among the 70 children studied, only 15.8% had previously demonstrated their inhaler technique to a physician.

During the study, 43 patients reduced error rate, 11 did not improve and 16 had a correct technique since the beginning.

The influence of inhaler technique demonstration on error rate over time was analyzed in the subgroup of 51 patients which completed the protocol. Over successive assessments, the number of errors decreased substantially in inhaler technique (p-value 0.019), mouthwash (p-value 0.000) and spacer care (p-value 0.038). However, Table 3 shows that relative distribution of different error types did not vary significantly over sequential visits (Fisher test p-value 0.42).

We attempted to establish a relationship between error rate and the different sociodemographic and clinical variables in Table 4. The only factors that reduced error rate were previous technique demonstration (p-value 0.003) and preceding inhaler-user (p-value 0.038). Nevertheless, there was only one child handling his own inhaler, which is insufficient evidence to draw conclusions.

Table 1: Patient sociodemographic, clinical and therapeutic data.

| Sample size (n) | 100 |

| Child’s age (years old; mean ± SD) | 2.8 ± 1.9 |

| Gender (n) | |

| - Male | 63 |

| - Female | 33 |

| - Not registered | 4 |

| Diagnosis (n) | |

| - Muli-trigger recurrent wheezing | 33 |

| - Viral-triggered recurrent wheezing | 20 |

| - Unspecified recurrent wheezing | 25 |

| - Asthma | 22 |

| Medication (n) | |

| - Inhaled corticosteroids | 50 |

| - Inhaled corticosteroids + montelukast | 24 |

| - Inhaled corticosteroids + long-acting beta agonist (LABA) + short-acting beta agonist (quick-relief) | 12 |

| - Inhaled corticosteroids + LABA + montelukast + short-acting beta agonist (quick-relief) | 5 |

| - Short-acting beta agonist (quick-relief) | 6 |

| - Inhaled corticosteroids + Anti-histaminic | 2 |

| - Missing data | 1 |

| Child's caregiver marital status (n) | |

| - Married | 43 |

| - Cohabiting | 43 |

| - Divorced | 5 |

| - Single | 8 |

| - Unknown | 1 |

| Caregiver responsible of inhaler (n) | |

| - Mother | 60 |

| - Father | 7 |

| - Both parents | 25 |

| - Parents + Grandparents | 2 |

| - Parents + childcare worker | 2 |

| - Patient himself | 1 |

| - Unknown | 3 |

| Mother’s age (years old; mean ± SD) | 33.4 ± 5.8 |

| Father’s age (years old; mean ± SD) | 34.9 ± 6.2 |

| Mother education (n) | |

| - Primary | 45 |

| - High School | 40 |

| - College | 14 |

| - Student | 1 |

| Father education (n) | |

| - Primary | 45 |

| - High School | 35 |

| - College | 9 |

| - Unknown | 11 |

| Familiar history of atopy (n) | |

| - yes | 57 |

| - no | 40 |

Table 2: Error rate in inhaler technique, mouthwash and spacer care.

| Frequency (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| V1 | V2 | V3 | |

| INHALER TECHNIQUE | |||

| - 0 errors | 64.7 | 80.4 | 90.2 |

| - 1 error | 27.5 | 17.6 | 9.8 |

| - 2 errors | 2 | 3 | 0 |

| - 3 errors | 5.9 | 0 | 0 |

| - Mean number of errors (s.e.m.) | 0.49 (0.11) | 0.22 (0.06) | 0.10 (0.04) |

| p-value (Fisher test): 0.019 | |||

| MOUTHWASH (IF CORTICOTHERAPY) | |||

| - 0 errors (yes) | 64 | 92 | 96 |

| - 1 error (no) | 36 | 8 | 4 |

| - Mean number of errors (s.e.m.) | 0.36 (0.07) | 0.08 (0.04) | 0.04 (0.03) |

| p-value (Fisher test): 0.000 | |||

| SPACER CARE | |||

| - 0 errors | 73.5 | 91.8 | 91.8 |

| - 1 error | 20.4 | 6.1 | 8.2 |

| - 2 errors | 61 | 2 | 0 |

| - 3 errors | 59 | 0 | 0 |

| - Mean number of errors (s.e.m.) | 0.33 (0.08) | 0.10 (0.05) | 0.08 (0.04) |

| p-value (Fisher test): 0.038 | |||

Legend: s.e.m. - standard error of the mean.

Table 3: Frequency of mistakes observed during the three clinical assessments.

| Error Type | Fraction of children/caregiver (%) | Frequency within assessment (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V1 | V2 | V3 | V1 | V2 | V3 | |

| Correct child position | 6.0 | 4.3 | 1.9 | 4.4 | 9.9 | 8.2 |

| Remove the cap | 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Shake inhaler | 28.0 | 10.0 | 1.9 | 20.6 | 23.0 | 8.2 |

| Mask correctly adapted | 4.0 | 1.4 | 1.9 | 2.9 | 3.2 | 8.2 |

| No air leakage | 5.0 | 1.4 | 0.0 | 3.7 | 3.2 | 0.0 |

| Press inhaler canister | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Counting 10 seconds while breathing normally | 12.0 | 2.9 | 1.9 | 8.8 | 6.7 | 8.2 |

| Wait at least 30 seconds to repeat | 7.1 | 7.1 | 3.8 | 5.2 | 16.4 | 16.4 |

| Wash the mouth at the end (corticosteroids) | 43.0 | 7.4 | 4.0 | 31.6 | 17.1 | 17.2 |

| Hand wash the spacer | 10.3 | 1.5 | 0.0 | 7.6 | 3.4 | 0.0 |

| Air dry the spacer | 19.6 | 7.4 | 7.8 | 14.5 | 17.1 | 33.6 |

Table 4: Relation between sociodemographic data and errors.

| p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| ≥ 1 error in inhalation technique | no mouthwash | ≥ 1 error in spacer care | |

| Age at the beginning of the study (Wilcox) | 0.144 | 0.714 | 0.779 |

| Gender (Fisher) | 0.383 | 0.263 | 0.676 |

| Diagnosis (Fisher) | 0.424 | 0.994 | 0.926 |

| Mother age (Wilcox) | 0.350 | 0.922 | 0.548 |

| Father age (Wilcox) | 0.581 | 0.569 | 0.793 |

| Mother education (Fisher) | 0.263 | 0.412 | 0.670 |

| Father education (Fisher) | 0.711 | 0.746 | 0.310 |

| Parents’ marital status (Fisher) | 0.901 | 0.590 | 0.624 |

| Family history (Fisher) | 0.832 | 0.388 | 0.805 |

| Who manage inhaler device (Fisher) | 0.037 | 0.935 | 0.242 |

| Medication drugs (Fisher) | 0.908 | 0.665 | 0.819 |

| Duration of medication (Wilcox) | 0.094 | 0.429 | 0.650 |

| Previous demonstration of inhaler technique (Fisher) | 0.003 | 0.569 | 1 |

| Time passed since last demonstration (Wilcox) | 0.340 | 0.127 | 0.298 |

Discussion

Only half of the patients completed the three-phase evaluation because patients do not usually take their inhalation equipment to medical visits, even if advised to. Besides that, some patients/caregivers did not even know their specific therapeutic plan, offered in written at each appointment. An inappropriate inhaler technique is a major obstacle to achieving good asthma control and may lead to overmedication and raised healthcare costs.1,2) Uncontrolled disease increases health resources consumption through more unscheduled clinic visits, emergency department visits and hospital admissions.3,7 It may also lead to frustration and worse therapeutic compliance.3

Error rate is higher in the first evaluation, except in those who had previously demonstrated their technique. In our study, only a small percentage of patients revealed a correct inhaler technique since the beginning (16.0%). In a similar study in North Carolina, Sleath observed that only 8.1% of children managed MDI correctly.7

The most frequent mistakes described by Sleath were related to (1) exhaling normally before and (2) holding their breath for at least 10 seconds after inhaling.7 According to Fink, the most common errors were (1) hand-breath coordination, (2) low inspiratory flow, (3) too fast inspiratory flow and (4) inadequate shaking. In pediatric population, the use of a spacer allows to overcome some of these issues.3) In accordance with the literature, the most frequent mistakes observed in our study were (1) inadequate shaking of the inhaler, (2) not counting 10 seconds while breathing normally and (3) incorrect spacer cleaning. In addition, a quarter of the patients did not shake their inhaler device in advance and almost half of the patients taking corticosteroids did not wash their mouth after inhalation.

In our study, there was no correlation between error rate and the different sociodemographic variables analyzed. However, other studies reported an association with age, education status, previous inhaler instruction, comorbidities and socioeconomic status. A significant association was found between inhaler error and poor disease outcomes (exacerbations) and greater health-economic burden.14,15

Correct inhaler technique demonstration has immediate positive impact on error reduction, which is amplified when successive demonstrations are performed by physicians. Most authors suggest careful instruction, observation of technique, instruction leaflets and audio-visual support.1,3,9,16

Patient’s MDI technique is better when verbal information is accompanied by demonstration with a placebo inhaler or when compared to an instruction leaflet alone.2,9 Even with short appointment times, evidence suggests the importance of inhaler technique demonstration at each visit to improve respiratory health outcomes. During medical appointments, symptoms and medication are revised, but the physician has hardly enough time to adequately educate the patient and caregivers.3,7 Fink considered that management of chronic airway disease depends 10% on medication and 90% on education.3

The study sample was significantly reduced over time because patients have frequently forgotten to take their devices to medical appointments. Furthermore, the short follow-up period represents a limitation for assessing the sustainability of error rate reduction. Time between appointments was not standardized and the study relied on a random sample.

Conclusion

We conclude that at least one demonstration of correct inhaler technique reduces the number of observed errors. Even during short medical appointments, technique review takes only a few minutes and represents a critical improvement in patient’s technique and, presumably, in disease control.17,18 The impact of inhaler technique has been subjugated by clinicals, patients and caregivers, and can even be the limitative factor for an adequate control of disease.

This study reinforces the need of patient education and technique review at each medical appointment, using attractive leaflet to engage the patient, even the younger ones.