Introduction

Despite medical advances in diagnosis and goals of treatment among patients with cancer, the disease often ends up spreading, affecting different organs and systems.1 Metastatic bone disease reduces quality of life and entails a creeping decline in physical and mental fitness in cancer patients.1 Thirty to seventy percent of patients with cancer will present skeletal metastases, and the most common locations include the spine, ribs, pelvis, skull, and proximal femur.2

Metastatic bone lesions can be classified as lytic, blastic or mixed, mostly relying on the primary tumor histology.3 Bone metastases are frequently found in patients with solid malignant tumors such as breast cancer (65%-75%), prostate cancer (65%-90%), and lung cancer (17%-64%). In 70%-95% of patients with multiple myeloma (MM), bone metastases are also present.4

Bone lesions secondary to these tumors (especially breast but also prostate, lung, and MM) are frequently lytic, resulting in bone resorption, impending fractures and eventually pathologic fractures.5,6

The incidence of pathologic fractures in patients with metastatic bone disease varies between 10% and 30%, with the proximal femur being the most common site of fracture in long bones.7 Among them, 50% occur in the femoral neck, 30% in the subtrochanteric area and 20% in the trochanteric area.8 Pathologic fractures are a frequent cause of pain and may lead to functional decline and disability. It is estimated that 40% of patients with pathologic fractures survive for at least 6 months after their fracture, and 30% survive for more than one year.9

The effective treatment of patients with cancer and associated bone lesions demands a multidisciplinary team approach. In some patients, a non-surgical approach including radiotherapy, chemotherapy, hormonal therapy, or bisphosphonates is suitable.10-12

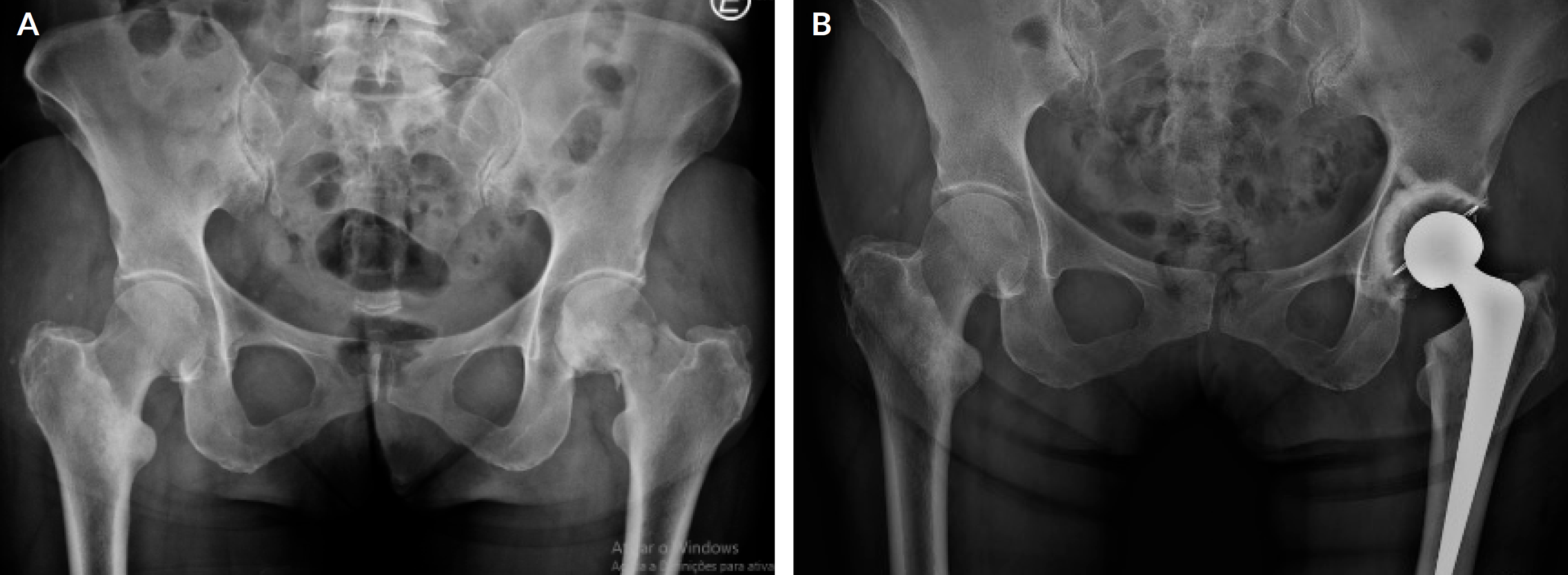

Figure 1 1A - Impending fracture of the right femoral shaft. 1B and C - Surgical stabilization of an impending fracture of the right femoral shaft with intramedullary nail.

Others may require surgical stabilization (Figs. 1A, B and C) or replacement of arthroplasty (Figs. 2A and B), especially when mechanical failures are present, such as in impending and actual fracture.13,14 In these patients, surgery aims to reduce pain, restore function, and improve quality of life.15 The type of intervention is variable and may be influenced by tumor stage, estimated patient longevity, predicted postoperative functional outcomes and the likelihood of a fracture.

In patients with an increased risk of fracture, prophylactic intervention should be considered, with several studies reporting the medical and financial benefits of surgical prophylactic intervention for impending fractures.16 Those include fewer postoperative complications and morbidity, shorter hospital stays, and early ambulation.17

This study aimed to evaluate oncologic outcomes and surgical complications in surgically treated patients with proximal femur bone metastases at one-year minimal follow-up treated in a single Portuguese center.

Material and methods

This is a 5-year retrospective study performed between 2017 and 2021 of 95 patients with metastatic bone disease surgically treated at our institution.

Among them, 37 patients presenting proximal femur metastases were included. Exclusion criteria were pediatric age (below 18 years old), non-operative treatment and missing data precluding follow-up evaluation.

Each patient’s clinical record was evaluated by three authors (JPP, MN and JSB). Variables of interest included demographic characteristics, cancer type, pathologic or impending fracture, surgical treatment options, surgery-related complications, overall patient survival (OS), and length of hospital stay (LOS). The impending fracture was defined with a Mirels’ criteria > 9 points (Table 1) or a symptomatic lesion observed on plain radiographs or other imaging techniques but without visible fracture documented.18

Table 1 Mirel's scoring system for metastatic bone disease

| Score | 1 point | 2 points | 3 points |

| Site | Upper limb | Lower limb | Trochanteric |

| Pain | Mild | Moderate | Functional |

| X-ray appearence | Blastic | Mixed | Lytic |

| Size of lesion | < 1/3 | 1/3 - 2/3 | >2/3 |

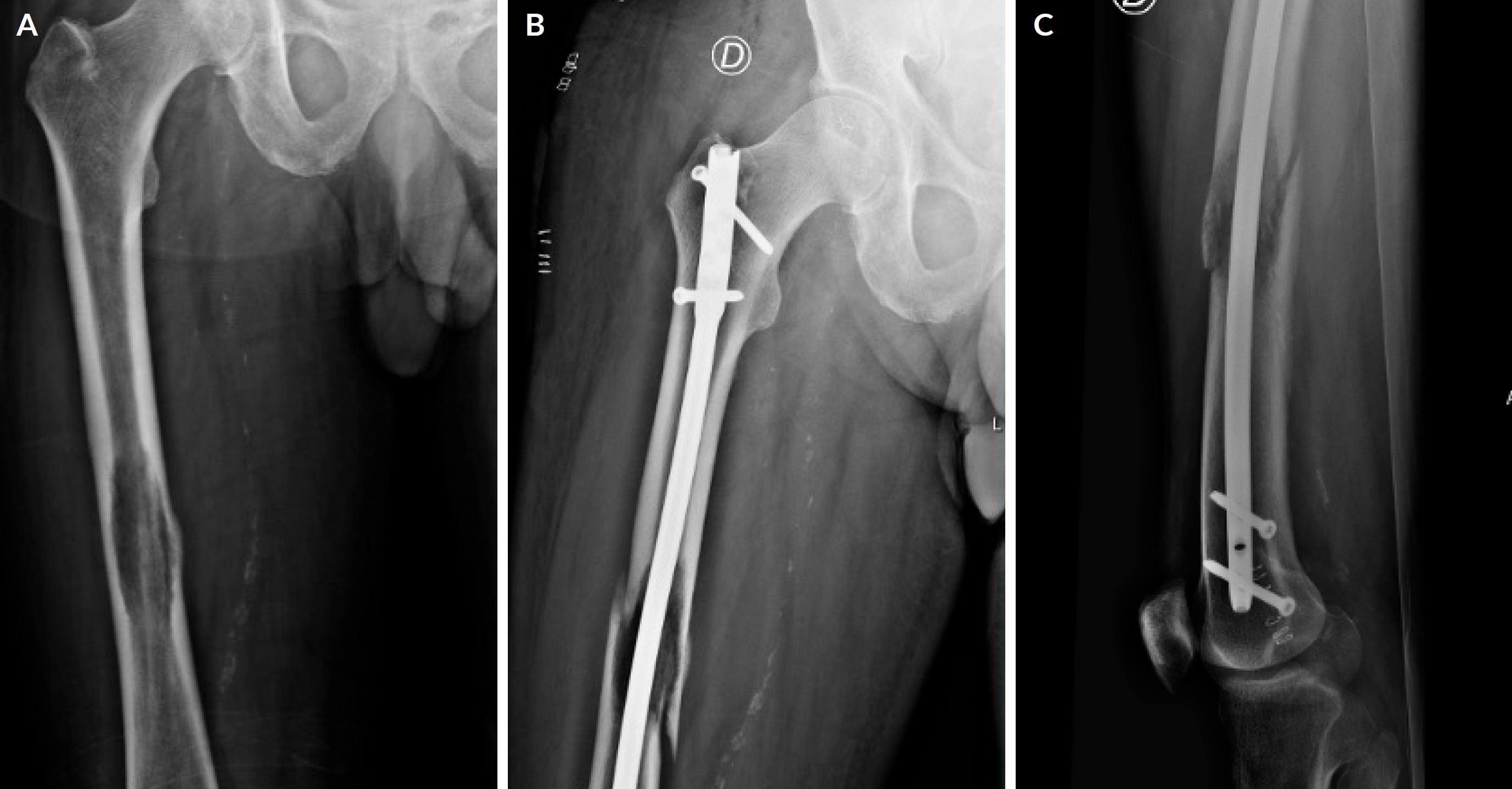

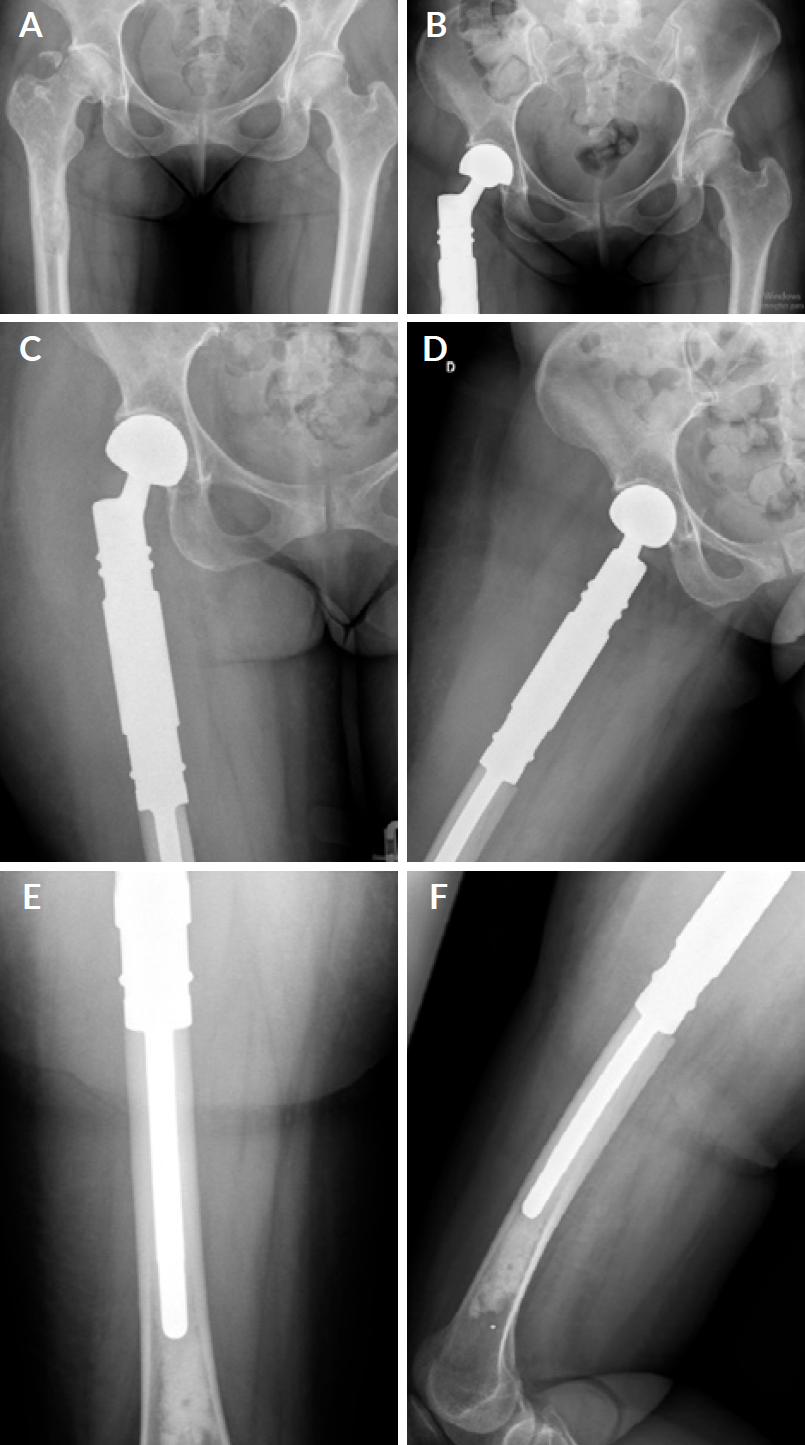

Surgical treatment options included en bloc resection and megaprosthetic reconstruction (Figs. 3A, B, C, D, E and F), osteosynthesis or conventional hemiarthroplasty/total hip arthroplasty. All surgeries were performed by the senior authors. OS was defined as the time from the fracture or impending fracture diagnosis until the date of death. We considered as relevant surgical-related complications those which implicated the need for new surgical procedures. The remaining complications managed without surgical treatment were classified as non-relevant.

Figure 3 3A - Proximal femur pathologic fracture due to lung cancer bone metastasis. 3B, C, D, E and F- En bloc resection and endoprosthetic reconstruction of the right femur.

Data analysis was performed using SPSS 23.0. Survival rates were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method and log-rank test. Cumulative intervals were analyzed using Microsoft Excel. Independent-sample T-tests were used to compare means. Statistical significance was defined as p<0.05, and 95% CI.

All data were anonymized to protect the privacy and confidentiality of participants. This study followed the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki and written informed consents for surgical and clinical data collection for scientific purposes were obtained from all patients at admission and before surgery according to our institutional protocol.

Results

Ninety-five patients with metastatic bone disease were surgically treated at our institution within the study period. Among these, we were able to track and evaluate 37 patients with proximal femur metastases.

Twenty-nine patients presented with pathologic fractures, while eight had an impending fracture. The length of stay was longer for patients with pathologic

fractures (Table 2).

Table 2 Patient’s demographics and length of hospital stay.

| Pathologic fracture | Impending fracture | |

|---|---|---|

| N | 29 | 8 |

| Age (years) | 67.3 ± 17.3 | 56.8 ± 11.6 |

| Gender (female) | 13 | 4 |

| LOS (days) | 15.8 ± 14.3 | 6.8 ± 2.9 |

Twenty-six patients underwent osteosynthesis or conventional hemiarthroplasty/total hip arthroplasty, while an en bloc resection with endoprosthetic reconstruction using megaprosthesis was performed in the remaining 11 cases (Table 3). Among patients who underwent metastasis resection and reconstruction with megaprosthesis, six had one bone metastasis and seven presented multiple bone metastases. For the remaining 26 patients where osteosynthesis or conventional hemiarthroplasty/total hip arthroplasty was performed, 12 had one metastasis, and 14 presented multiple metastases.

Nine patients had lung cancer metastases, eight had breast cancer metastases, seven had prostatic cancer secondary lesions, four other presented uterine cancer secondary lesions, three cases were secondary to kidney cancer, and six patients had multiple myeloma lesions.

Table 3 Type of procedure and number of metastases,

| N= 26 | N=11 | |

| Procedure | Osteosynthesis/ arthroplasty | Resection with reconstruction |

| M*=1 | 12 | 6 |

| M*>1 | 14 | 7 |

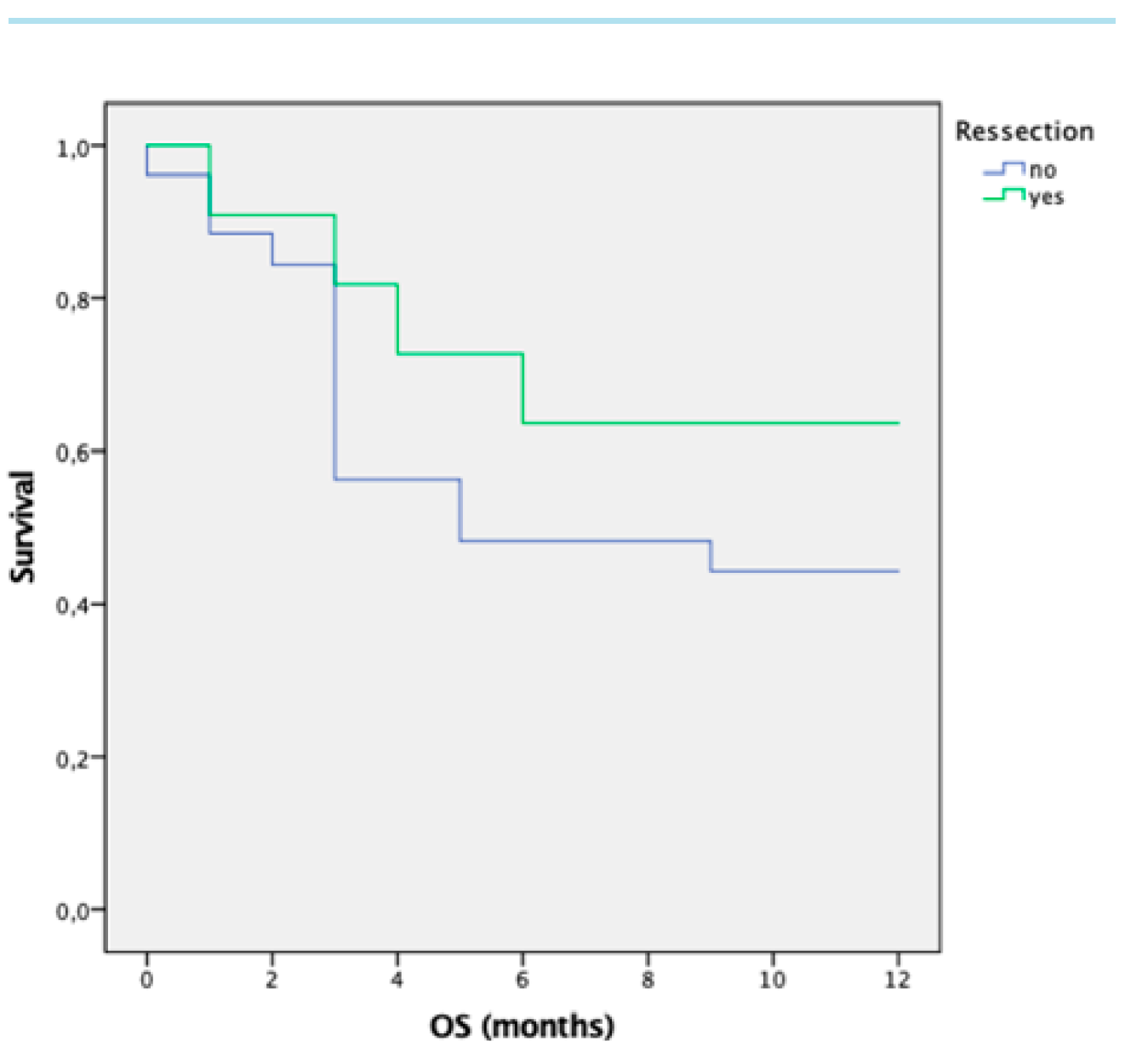

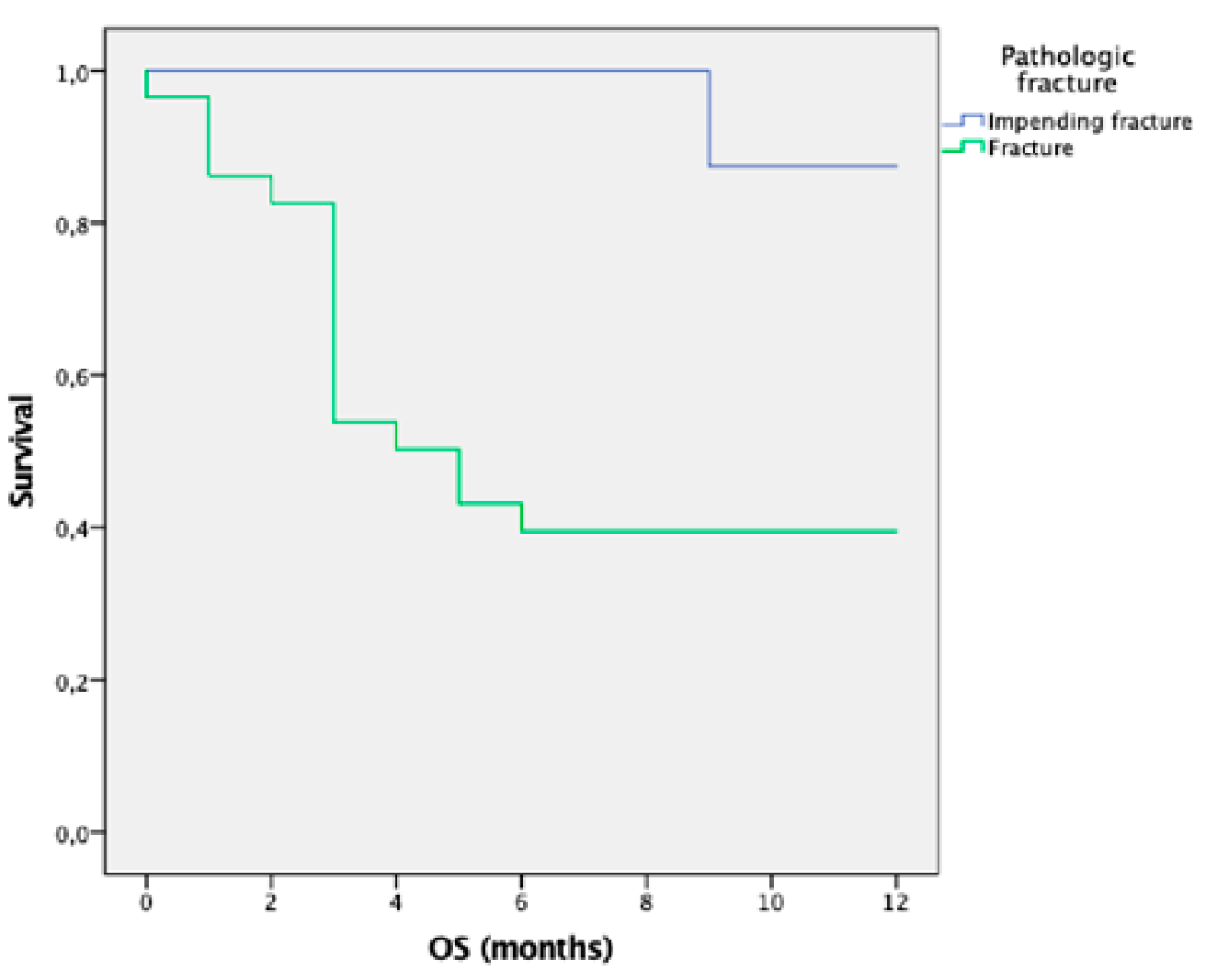

Patient’s OS at one year was higher for those where metastatic en bloc resection and bone reconstruction were performed, although no statistical differences were found (70% vs 50%, p=0.231) - Fig. 4. The 1-year OS was also higher for patients with breast (80%) and prostate (75%) cancers, while patients with uterine and lung cancer presented the lowest 1-year OS (0%), p=0.016, p<0.05. The OS for patients presenting with impending fractures was also significantly higher when compared with those presenting with actual pathologic fractures (90% vs 40%, p=0.018, p<0.05) - Fig. 5.

Figure 4 1 year-overall-survival of cancer patients with metastatic resection and joint reconstruction vs fixation.

Figure 5 1 year-overall-survival of cancer patients with pathologic factures and impending fractures.

Only one new surgical procedure was required due to infection within the resection group. On that occasion, the authors performed aggressive surgical debridement, implant removal, and spacer introduction. No other relevant complications were reported.

Discussion

This study evaluating outcomes for metastatic patients with proximal femur fractures or impending fractures presented a higher overall survival for those patients treated without fracture occurrence. Furthermore, it seems that en bloc resection and megaprosthetic reconstruction also benefit survival when compared with those cases where metastasis resection was not performed, and patients with breast carcinoma proximal femur bone metastases present a better chance of survival at one year of follow-up.

The number of patients living with bone metastases increases as medical and surgical treatments improve the overall survival of patients with cancer. In 1989, Mirels proposed a score to quantify the risk of a cancer patient with appendicular bone metastases sustaining a pathologic fracture. The author suggested that lesions with scores of nine or higher should undergo prophylactic stabilization, having a risk of 33% for a pathologic fracture to occur.18 Shinoda et al reported that a computed tomography (CT) scan should be used to predict the risk of pathologic fracture. These authors suggested that if there is an involvement of 25%-50% of the medial cortical in the proximal femur, surgery should be indicated.19

Our findings suggest that prophylactic stabilization promoted a significantly better OS when compared to patients with a pathologic fracture, which was previously reported in the literature.20-22 In a sample that included 558 patients with femoral metastatic lesions surgically treated between 1992 and 1997, Ristevski et al reported that patients who underwent prophylactic stabilizations had better OS, even after adjusting for age, sex comorbidities and type of cancer.20 Similar results were described by Phillipp et al in a study that included 950 patients with proximal and shaft femoral fractures treated between 2010 and 2015, with a mean follow-up of 2 years. They reported that after adjusting for comorbidities and type of cancer, patients with a pathologic fracture had a higher risk of death when compared to patients with impending fractures.21 Overall, the general recommendation became to, whenever possible, surgically approach all impending fractures to prevent fractures and a worse prognosis with it. We could not identify a simple reason behind the better survival in patients where prophylactic stabilization was performed. Some studies suggest that prophylactic measures in these patients are associated with lower immediate mortality, improved ambulation, and shorter hospital stays, which in turn can exert an influence on survival.22 Also, we could theorize that elective prophylactic surgery may allow for preoperative optimization of patients with known comorbidities instead of acute fracture stabilization in an emergent setting. According to Ristevski et al, the presence of a fracture is associated with an extra five days of hospital stay, mostly related to delayed surgery, postoperative complications and slower mobilization.20 Our findings were similar, with patients presenting pathologic fractures also having a diminished OS and significantly longer hospital stays when compared to patients with impending fractures. We must stress that the relation between pathologic fractures and lower OS is most likely multifactorial, with patients who suffered pathologic fractures eventually presenting a more aggressive and extensive disease. We could also hypothesize that the presence of a proximal femoral fracture per se represents a risk factor for higher mortality, as it is for elderly patients who sustain this type of fracture.23

Within this series, we also found that patients with metastatic femoral lesions from breast cancer had better one-year OS when compared with other primary tumors, namely lung cancer, which was responsible for the lower OS among all histologic subtypes.

Studies have shown that the 5-year relative survival for breast cancer patients has increased from 75% in the mid-70s to 90% for patients diagnosed between 2011 and 2017.24 These findings might be explained by the increasing number of mammography screenings and breast cancer screening campaigns, which can potentially detect disease at its early stages. Additionally, advances in drug development such as chemotherapy, hormone therapy, and targeted drugs and innovations in pathology and molecular biology over the last years play a significant role in the OS of patients with breast cancer.25 On the other hand, lung cancers are typically more aggressive, and despite the advances in treatment options, because early disease is usually asymptomatic, most lung cancers are advanced at the time of diagnosis. According to the SEER program (surveillance, epidemiology, and results), only 30% of lung cancers are diagnosed at an early stage, having a 5-year survival rate of 65%, which declines to 5% with advanced stages.26,27

Several ways to manage metastatic bone lesions have been described. Treatment options include conventional osteosynthesis with intramedullary nail or plate, conventional prosthesis, and modular megaprosthesis, as the decision is often influenced by the type of lesion and patient status. Conventional osteosynthesis to stabilize the lesion often allows minimally invasive approaches reducing intraoperative blood loss and surgical timing, representing a favorable option when considering frail patients with advanced metastatic disease.28 However, metastatic bone resection and reconstruction represent the best surgical option as they significantly decrease pain, improve function, and reduce the risk of recurrence. In fact, in a study with 67 patients with metastatic bone disease, Guzik reported that radical metastatic tumor resection is a necessary condition to achieve good outcomes, preventing local recurrence, providing pain relief and early mobilization.29 As seen in our study, this author also suggests that the overall survival is higher for patients where metastatic bone resection was performed. Additionally, several other authors reported improved OS in patients whose surgery includes metastasis resection, depending on the type of cancer and grade of malignancy.30,31

As presented above, hospital stay was significantly longer among patients with pathologic fractures when compared to those with impending fractures. Despite the impossibility of calculating the costs associated with pathologic and impending fractures, it is straightforward that with longer hospital stays, usually seen with pathologic fractures, come higher healthcare-associated costs. In this regard, there are very few studies reporting on the economic burden of bone metastatic disease or pathologic fractures. However, the costs associated with bone metastases in cancer patients within the US from 2000 to 2004 were estimated to be $12.6 billion per year. (32 Also, Jairam V et al reported higher cost-of-hospital-stay in patients with skeletal pathologic fractures. (33 Another study dealing with lower extremity metastatic bone disease reported that lower extremity prophylactic fixation was associated with decreased treatment costs and hospitalization length.34 Altogether, the direct and indirect financial and human costs related to metastatic bone disease seem to be considerably higher if pathologic fractures occur.

This study suggests the importance of early detection for impending fractures in patients with bone metastases, particularly on the proximal femur. This means a higher awareness from the medical oncologists and radio-oncologists who usually follow and manage these patients, which should promote timelier orthopedic consultation. Although similar findings have been well established in the international literature, this study is, to our knowledge, the first to report these findings concerning the Portuguese population.

We acknowledge the retrospective nature of the study and the small cohort sample as limitations. Nonetheless, this study is limited to a single institution, and we will continue to assess patients who have undergone surgery for bone metastases.

Conclusion

Despite the advances in the management of patients with metastatic bone disease, its treatment remains complex and challenging, reinforcing the need for a multidisciplinary approach, including routine evaluation by non-orthopedic specialists of skeletal complaints but also early referral for orthopedic evaluation.

OS for patients with proximal femoral metastases seems to be influenced by primary tumor histology, type of surgical treatment and the presence of pathologic fracture at diagnosis. This evidence should encourage thorough periodic follow-ups regarding bone metastatic disease and low threshold for medical and surgical approaches to prevent pathologic fractures and achieve optimized outcomes.