Introduction

Congenital malformations affect around 3% of newborns, with male sex prevalence.1 Gastrointestinal (GI) malformations are the third most common, with an incidence of 15%, being esophageal atresia (EA), anorectal malformation (ARM) and Hirschsprung’s disease the most prevalent.2

EA is a rare congenital malformation, with incidence of 1/3000-4500 live births worldwide, in which the esophagus fails to develop, ending blindly as a pouch in the thorax, with or without tracheoesophageal fistula (TEF), leading to an interruption in esophageal continuity.3,4

This pathology etiology is not completely understood; however, it is believed that it is multifactorial, with strong evidence of a genetic factor, probably polygenic. It is reported that the progeny of former EA patients has an increased risk.5 Additionally, 6%-10% of EA newborns have an association with chromosomal abnormalities, such as trisomy 13, 18 (the most related to EA) and 21 and some deletions (13q-, 17q- and 22q11-).5,6 Moreover, three genomic regions, on chromosome 10q21, 16q24 and 17q12, were identified as being possibly correlated to EA development.5

Furthermore, it is demonstrated that 50%-70% of the EA patients have other congenital defects, the most common being the cardiac ones (24%).7 When we have an association of three or more anomalies, the diagnosis of VACTERL (vertebral, anal, cardiac, tracheal, esophageal, renal, limb) is suggested.8,9 Another possible anomaly association is CHARGE (coloboma, hearth, choanal atresia, retarded growth, genital hypoplasia, ear deformities).9

The EA/TEF can be divided into five categories according to Gross classification, in relation with TEF presence/location: Type A - EA with no TEF (7%-8% of all the EA); Type B - EA with proximal TEF (1%-4%); Type C - EA with distal TEF (85%, the most common); Type D - EA with proximal and distal TEF (3%-4%); Type E (H-type) - isolated TEF (3%-4%).8

Usually, EA diagnosis is made in the first hours of life, suspected through signs such as drooling, regurgitation, coughing, gagging and respiratory distress (apneic episodes/cyanosis) specially during feeding.8 A chest radiography taken with an nasogastric (NG) tube is mandatory, where a rolled-up tube in the proximal esophagus is diagnostic of EA.10 However, ultrasound prenatal suspected diagnosis is sometimes already present: polyhydramnios and absence of gastric vesicle are the most used parameters, but they can be found in other pathologies and the latter is present in the absence of distal TEF, hence lacking specificity. Other parameters like the detection of neck or chest sac from 32 weeks of gestation, known as the pouch sign, and the non-visualization of the lower thoracic esophagus are recently reported as more reliable. Nevertheless, only one-third of EA cases are identified prenatally.11 Other exams, such as echocardiography, abdominal/pelvic ultrasound and bronchoscopy, should be performed to evaluate other malformations and for anesthetic/surgical purposes.12

EA newborns demand monitoring in Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU): they need head elevation and continuous saliva aspiration to prevent apnea and aspiration pneumonia. Furthermore, endotracheal intubation should be avoided to prevent iatrogenic gastric perforation.13 The definitive treatment is the primary correction of EA/TEF, with an end-to-end anastomosis to reestablish esophageal continuity.9 The prognosis is favorable, with 90%-95% survival,8 being the majority of the deaths attributed to associated congenital anomalies and sepsis.14 Despite this, EA is associated with comorbidities, such as esophageal stenosis, dysphagia and gastroesophageal reflux (GER), that may require medication, surgery or other treatment techniques, affecting quality of life.15 EA survivors are at fourfold increased risk of Barrett esophagus,16 which leads to higher risk of adenocarcinoma and epidermoid carcinoma, warranting dedicated surveillance through adulthood.7,8

This study aimed to retrospectively characterize the cases of EA at Daniel de Matos Maternity (DMM), Centro Hospitalar e Universitário de Coimbra (CHUC), in the last 15 years, analyzing the Gross classification, risk factors, prenatal diagnosis, delivery, preoperative care, treatment and morbimortality of EA neonates.

Material and methods

After permission from CHUC ethics committee, a retrospective anonymized descriptive study of 18 newborns with an EA diagnosis was performed. Inclusion criteria comprised of all neonates born between January 2007 - December 2021, diagnosed with EA, admitted to the NICU of the DMM (tertiary care referral center in Coimbra), obtained by searching the EA code on the unit’s neonatal database and using the clinical key coding list.

Demographic and clinical data were collected from the medical records of EA neonates and were stored in a Microsoft Excel table. Different instruments were used: for prenatal data information in the neonate clinical record was used; postnatal and NICU data relied on Apgar score, chest radiography with NG tube and regular monitoring analysis; to assess cardiac anomalies, an echocardiogram was performed; EA type was classified using Gross classification.

The variables analyzed included: mother’s age, previous gestations, pregnancy surveillance, events and ultrasounds, EA prenatal suspicion, polyhydramnios /other anomalies in ultrasound, fetal growth restriction (FGR), type of birth, sex attributed at birth, birth weight (BW), complete gestational age (GA), Apgar score, resuscitation, chest radiography with NG tube, ventilation, continuous saliva aspiration, antibiotics, NICU complications, hours of life at transfer, echocardiogram, other congenital anomalies, surgery type, days of life at surgery, EA type, mortality and comorbidities.

IBM SPSS Statistics 28.0 was used to analyze the variables: mean/mode used on quantitative variables, while frequency percentages/counts used on qualitative variables were converted into numerical ones. A Fisher’s Exact Test of independence was performed to examine the relation between polyhydramnios and FGR and between FGR and hypoglycemia. A Mann-Whitney U test was employed to assess whether a difference exists between the complete GA at birth of pregnancies previously with and without polyhydramnios and to evaluate whether a difference exists between complete GA at birth of pregnancies previously with and without prenatal suspicion of EA. It was considered statistically significant when p<0.05.

Results

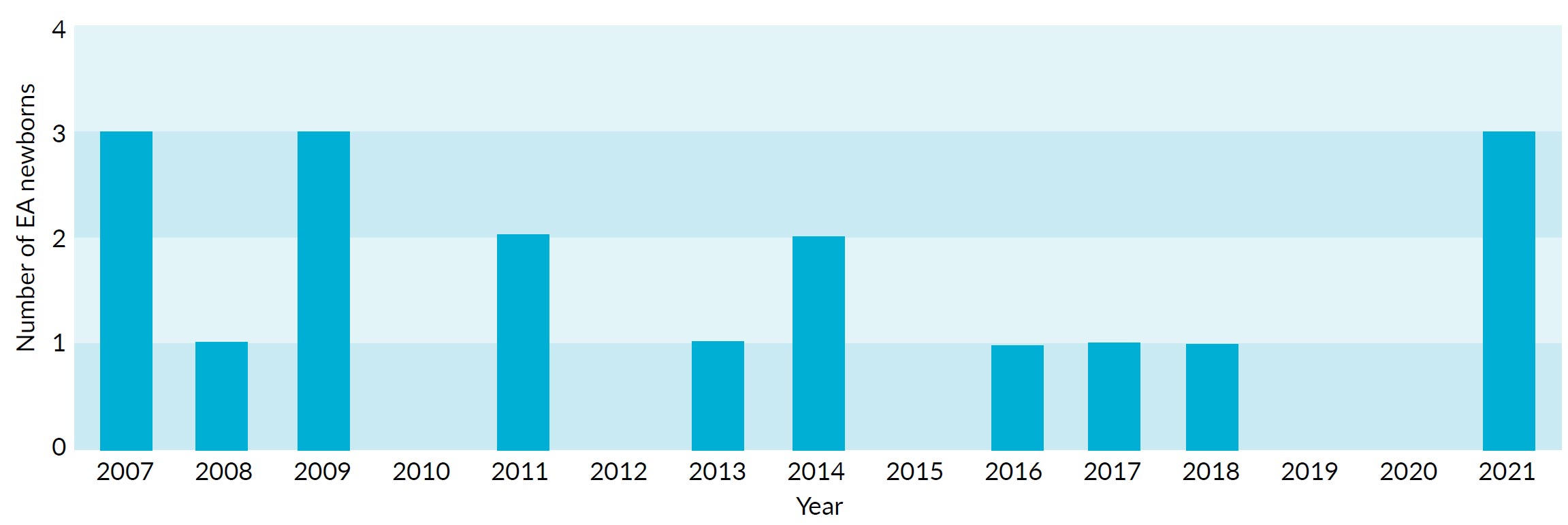

Between 2007 and 2021, the NICU of the DMM in Coimbra received 18 newborns with an EA diagnosis. The yearly cases distribution varied from 0-3 cases per year (Fig. 1).

The demographic and obstetrics data of these newborns are described in Table 1. Of the 18 pregnant women, 10 (55.5%) had at least one event during pregnancy (Table 2) and 4 (22.2%) had Group B Streptococcus colonization.

Table 1:Demographic and prenatal data of newborns with EA diagnosis (n=18).

| Number | (%) | Devition | |||

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 10 | 55.6 | |||

| Male | 8 | 44.4 | |||

| Mather's age (years) | 30.6 | ±5.9 | |||

| Number gestations | 1.7 | ±0.8 | 1 | ||

| Pregnancy Suveilance | |||||

| Private Clinic | 6 | 33.3 | |||

| District Hospital | 5 | 27.8 | |||

| Central Hospital | 7 | 38.9 | |||

| Number of Ultrasounds | 3.8 | ±0.9 | 3 | ||

Table 2: Events reported during pregnancy (n=18).

| Variables | Absolute Number | Frequency (%) | |

| Fetus Eventes | 5 | 27.8 | |

| Amniocenteses | 4 | 22.2 | |

| Abnormal cardiotocography | 2 | 11.1 | |

| Maternal Events | 2 | 11.1 | |

| Gestational diabetes | 1 | 5.6 | |

| Preeclampsia | 1 | 5.6 | |

| Threatened Preterm Labor | 2 | 11.1 | |

| Other Eventes | |||

| Contractions/Pelvic pain | 1 | 11.1 | |

| Induced labor | 1 | 5.6 | |

| Erysipelas infection | 1 | 5.6 | |

EA’s suspected prenatal diagnosis was present in 33.3% (6 cases), reported between 21-33 weeks of gestation, with a mean of 25.8 ± 5.0 weeks, and equal distribution along 15 years. In the ultrasound, polyhydramnios was present in 61.1% (11 cases) of all the pregnancies (100% when prenatal diagnosis was suspected) whereas other morphologic anomalies were present in 33.3% (6 cases), being the non-visualization/reduction of the stomach the most common (66.7% of the other anomalies, 22.2% of all pregnancies - 4 cases, with concomitant polyhydramnios). Considering EA type A, 100% (2 cases) had EA prenatal suspicion, having polyhydramnios and non-visualization of the stomach present. FGR was present in 44.4% of the cases (8 cases). The relation between polyhydramnios and FGR was non-significant (p = 0.630). Of the 61.1% of the pregnancies not monitored in a central hospital (11 cases), 100% were transferred in-uterus to the DMM, out of these 63.6% (7 cases) had polyhydramnios and 18.2% (2 cases) had EA suspicion.

In regard to delivery, there was an equal distribution between cesarian and vaginal births (Table 3). After adjusting for pregnancies with polyhydramnios and prenatal EA suspicion, statistically significant differences were found between the complete GA at birth in pregnancies with polyhydramnios (median 35 weeks) and pregnancies without polyhydramnios (median 37 weeks); U=16.0; p = 0.038. However, no statistically significant differences between the complete GA at birth in pregnancies with prenatal EA suspicion (median 36 weeks) and pregnancies without it (median 37 weeks) were found; U=32.0; p = 0.704.

Table 3: Delivery data of all the pregnancies, the ones with polyhydramnios and the ones with prenatal suspicion of EA (n=18).

| Variables | Absolute Number | Frequency (%) | Mean | Standard Deviation |

| All Pregnancies | 18 | 100.0 | ||

| BW (g) | 2276.4 | ±727.6 | ||

| Complete GA (weeks) | 35.7 | ±3.1 | ||

| Type of delivery | ||||

| Cesarian | 9 | 50.0 | ||

| Vaginal | 9 | 50.0 | ||

| Pregnancies with Polyhydramnios | 11 | 61.1 | ||

| BW (g) | 2183.6 | ±781.1 | ||

| Complete GA (weeks) | 34.7 | ±3.0 | ||

| Type of delivery | ||||

| Cesarian | 7 | 63.6 | ||

| Vaginal | 4 | 36.4 | ||

| Pregnancies with Prenatal EA Suspicton | 6 | 33.3 | ||

| BW (g) | 2297.5 | ±391.3 | ||

| Complete GA (weeks) | 36.0 | ±0.9 | ||

| Type of delivery | ||||

| Cesarian | 4 | 66.7 | ||

| Vaginal | 2 | 33.3 | ||

The Apgar Score had a mean of: 7.4 ± 2.1 - first minute; 9.0 ± 1.3 - fifth minute; and 9.6 ± 1.0 - tenth minute; with a mode of 9, 10 and 10 respectively. Resuscitation was necessary in 27.8% (5 cases): positive pressure ventilation - 3 cases (16.7%); endotracheal tube - 2 cases (11.1%).

During NICU stay, all newborns performed an X-ray with an NG tube and an echocardiogram. Ventilatory support was necessary in 16.7% of the neonates (3 cases): one with extremely low birth weight (ELBW) and extreme prematurity (28 weeks), very low BW and prematurity (32 weeks) and the third case was a newborn with neonatal resuscitation, choanal atresia and retrognathism. Continuous aspiration was performed in 17 newborns (94.4%). Antibiotics were given in 44.4% (8 cases), mostly for prenatal infectious risk.

33.3% (6 cases) reported complications in the NICU, being the most common hypoglycemia (4 cases). The relation between FGR and hypoglycemia was non-significant (p = 0.618). Congenital anomalies were present in 66.7% (12 cases), being cardiac anomalies the most frequent in 50% (9 cases): among these, isolated IAC were the most common (27.8%), followed by simultaneous IAC with IVC (16.7%) and by isolated IVC (5.6%).

Other anomalies were present in 33.3% (6 cases): two cases of laryngeal clefts, one case of ARM, one case with minor dysmorphism, one CHARGE syndrome and one VACTERL association.

All newborns were transported by a neonatal inter-hospital transport team, with a mean of 11.1 ± 10.1 hours of life, to further evaluation by Pediatric Surgery. The latter were calculated with exclusion of one case with 96 hours of life at transfer for extreme prematurity (28 weeks) and ELBW (770 g). According to Gross classification, type C was the most frequent in 83.3% (15 cases), followed by type A in 11.1% (2 cases) and type B in 5.6% (1 case). Long-gap EA, less frequent than short-gap (27.8% versus 72.2%), corresponded to 100% of EA type A and 20.0% of EA type C (3 cases out of 15).

All neonates underwent anastomotic reconstruction of esophageal continuity: 17 newborns (94.4%) had primary reconstruction while one was submitted to Foker’s method. TEF correction was performed in all cases of EA types B/C (16 cases). Gastrostomy was necessary in 16.7% (3 cases). The mean of days of life at surgery was 2.5±0.9 days, with a mode of 2 days, these values were calculated with exclusion of a case where delayed surgery was performed (7 months later). When considering morbimortality, all newborns survived. The most frequent comorbidities were: GER - 72.2% (13 cases), esophageal stenosis - 55.6% (10 cases), dysphagia - 22.2% (4 cases) and esophagitis - 16.7% (3 cases).

Discussion

There was a relatively equal distribution between females and males, in line with previous data that EA has no sex preference,4,12 although some studies show that congenital malformations may display male sex preponderance.1,2,7

Despite being reported that advanced maternal age has a relation with EA development,2,7 in this study, the mean maternal age was below 35 years, with only four cases presenting advanced maternal age. It was also observed that most of the EA cases occurred on the first/second pregnancy, in concordance with previous studies that report that low birth number is a EA risk factor.7 More than half of the pregnant women had at least one event during pregnancy. It was previously reported that gestational diabetes, some maternal infections and exposure to some medications could be correlated to the presence of EA.2,7

All gestations were monitored, with equal distribution between private clinic, district hospital and central hospital/DMM. However, all pregnancies not monitored in a central hospital were transferred to it still in the uterus, mostly due to polyhydramnios/EA suspicion. This is in agreement with recommendations that when there is EA prenatal suspicion, the parents are advised for the birth to occur in a tertiary referral center hospital, with an NICU and a Pediatric Surgical Unit.13

Similar to previous reports, prenatal suspicion of EA was present in one third of the cases,11,13 which occurred between the twenty-first and thirty-third week of gestation, in line with literature stating that diagnosis occurs after the eighteenth week, in the second/third trimester.6,7 EA prenatal suspicion is based on the presence of polyhydramnios and non-visualization of the stomach at the ultrasound.7-11,13 Polyhydramnios was present in around 60% of the pregnancies, similarly to previous data, whereas the non-visualization/reduction of the stomach was less frequent.8 All EA type A had EA prenatal suspicion, in accordance with other authors who found that EA with no TEF had higher prenatal diagnosis report rates.8,13,15 There were no cases of detection of neck or chest sac (pouch sign), nor the non-visualization of the lower thoracic esophagus, in contrast with existing evidence.8,9,11,13

When comparing the type of birth in pregnancies with polyhydramnios and the ones with EA prenatal suspicion, the cesarian birth was the most common in both, whereas when considering all pregnancies there was equal distribution between cesarian and vaginal birth.

Although there was a prevalence of cesarian birth in pregnancies with EA prenatal suspicion, this was also the case in pregnancies with polyhydramnios. EA prenatal diagnosis is not a criterion for cesarian birth, occurring when other anomalies and problems are anticipated.13

The mean complete GA at birth was below 37 weeks, this was also the case when considering pregnancies with polyhydramnios/EA prenatal suspicion, in agreement with previous data reporting a higher incidence of EA in premature newborns, despite some studies concluding the opposite.4,7 It was also observed that the mean BW was below 2500 g, supported by other studies.7,12 Furthermore, a statistically significant difference was found between GA of pregnancies with polyhydramnios (lower GA) and without it. Polyhydramnios, implying larger amniotic fluid volume, is associated with increased risk of preterm labor.17 The Apgar score had only lower reports at the first minute. Resuscitation was necessary in a small number of cases, in association with the Apgar score (7 or lower at first minute).

As in other investigations, all newborns had a chest X-ray with an NG tube to verify the EA diagnosis.9,10,12,13

Continuous aspiration was regularly performed, as recommended, to prevent aspiration pneumonia.8,9,12,13

Spontaneous breathing is recommended in EA neonates.8,9,13 Ventilation was needed in a low percentage of neonates: two cases for prematurity and one case for polymalformative syndrome (confirmed lately as CHARGE). Ventilation should be avoided for the iatrogenic gastric perforation risk in TEF presence.8,9,13 Regarding antibiotics, they were used not only for EA, but also for prenatal infectious risk, such as extreme prematurity, premature rupture of membranes and fetal distress. There is not a consensus in whether antibiotic prophylaxis should always be used in EA newborns.9,13 A third of the neonates reported complications in the NICU, being the most common hypoglycemia, although it could be associated with FGR, no significant statistical association was demonstrated.18

It is generally accepted that more than 50% of EA newborns have at least one congenital malformation associated,5,7-9,15 in line with this study. Cardiac anomalies are described as the most commonly associated with EA, with incidences varying from 23% - 86%. In accordance, cardiac anomalies were present in half of the cases.3,4,7,9,13,14 Among them, IAC was the most common, followed by IVC, as in previous works.3,7 For this reason, an echocardiogram was always performed.8,13

Other congenital anomalies were present in one third of cases, in accordance to other studies3: two laryngeal clefts and one ARM, supporting previous reports, stating higher incidences of these in EA patients.8,9,12 Furthermore, it was found one case of CHARGE syndrome and one suspicion of VACTERL association, which are strongly associated to EA, the latter having prevalence’s around 10%.3,4,8-10,15

EA type C was the most frequent, followed by type A.1,3,10-12,15 There was one case of EA type B and types D/E were not found as they are less common.7-9,13 EA can be divided in short-gap and long-gap, the latter is usually characterized by a gap longer than 2-3 cm or higher than 2 vertebral bodies, being more common in EA type A/B.4,9,19 Prevalence of short-gap EA was found, with 30% of long-gap EA (confirmed in all EA type A), in accordance to other studies where long-gap EA had a prevalence of 10%-30%.15,19

Surgery was performed mostly on the second day, in line with previous studies that report that EA correction should be performed in the first days of life, to reduce mortality.3,6,8,20 All newborns underwent anastomotic reconstruction of esophageal continuity, as recommended.7-9,12,19,20 In the majority of the neonates the primary reconstruction was performed, with only one case (long-gap EA type C) of a two-step repair after Foker’s method - which consists in using traction sutures to enable esophageal stretching, mostly executed in long-gap EA, when primary reconstruction is not possible.4,9,19 Gastrostomy was necessary in three newborns: both EA type A and the long-gap EA type C that went through Foker’s method, as reported that gastrostomy was required in the majority of the long-gap EA or in the presence of a wide TEF with respiratory distress.19,20

There was no mortality reported in this study, as similar to prior records stating an increase in survival rate, greater than 90%, with mortality mostly occurring in those of extreme prematurity or other associated congenital anomalies.8,9,12,14,15,20

Comorbidities associated with EA are common, not only after birth, but also in the subsequent years of life,7,8,16 having prevalences around 90% in this study, with GER being the most frequent . Although other studies reported lower incidences, they still consider GER as a highly prevalent comorbidity.9,16 Esophageal stenosis followed GER, with frequencies slightly higher than previous data.9,15 Lastly, dysphagia and esophagitis were also present, with lower reports than previous works.8,15,16

This study has several limitations, such as: small sample size; its retrospective nature; for being a single-center work; and absence of a control group.

Conclusion

To conclude, EA remains a challenging pathology. An accurate EA prenatal suspicion would be of extreme importance to reduce morbimortality and to improve management of these neonates, with immediate monitoring in an NICU and a brief time to surgery. Despite advances in prenatal diagnosis, it was positive in only one-third of cases. Efforts should be made to improve detection rates and eventually consider novel markers.

After birth, it is important to confirm the diagnosis, EA type and check other malformations, since these can influence management. With increased survival, new studies should concern morbidity and quality of life of these children.