Introduction

The effect of bullying on adolescent self-esteem is a serious concern. The presently accumulated evidence shows a consistent link between being bullied and lower self-esteem. A study by Ayoub et al. (2021) in Tunisia revealed that over 95% of bullied teens had low self-esteem, compared to just 4.4% of their non-bullied peers. Surprisingly, bullies often have low self-esteem (Matorci et al., 2023). Other research shows bullying harms teens’ mental and social health, particularly girls’, impacting their self-image and emotional well-being. Studies suggest that both victims and perpetrators may struggle with self-worth. Research conclusions demonstrate the need for programs that build self-esteem to help protect young people from bullying’s damaging effects.

School plays a significant role in young people’s lives, enabling their social development. School climate is a multidimensional construct that can be defined as the set of beliefs, values, and attitudes present in the relationship between students, teachers, and staff at a school (Espelage & Hong, 2019). A positive school climate encompasses positive social relationships, discipline, and fair and conscious rules. Therefore, it is associated with better academic performance and positive outcomes. In other words, these interactions will contribute to adolescents’ satisfaction and well-being and less involvement in violent acts like bullying. However, this often does not happen nowadays, as students have a negative perception and weak connection with the school. Thus, school climate influences students’ behavior, self-esteem, self-concept, and activity involvement (Espelage & Hong, 2019).

Bullying is a form of intentional, persistent aggression characterized by a power imbalance affecting individuals’ physical, social, and emotional well-being (Espelage & Hong, 2019). It is intentional behavior, persistent and permanent against a victim who has no or few resources to defend themselves, consists of a power imbalance (Espelage & Hong, 2019), and happens whenever a child harms another who appears weaker/more vulnerable (Ang et al., 2018). There is, therefore, a need to make a conceptual distinction between persistent and systematic exposure to bullying behaviors and sporadic and transitory episodes, which is referred to as victimization. Thus, bullying can be characterized by repetition, harm, and inequality.

Research indicates a significant prevalence of peer victimization during adolescence, a developmental period characterized by heightened sensitivity to social dynamics and interpersonal relationships (Zhu, 2023). This phenomenon manifests with intensity during the teenage years, correlating with developmental stages where peer acceptance and social integration become paramount to identity formation.

Contemporary manifestations of peer aggression encompass multiple modalities, including traditional face-to-face confrontations and technology-mediated harassment. The latter has become an increasingly significant concern, given the ubiquitous nature of digital communication platforms in adolescent social ecology. This multi-modal nature of peer aggression presents unique challenges for intervention strategies.

Empirical evidence suggests cascading effects across various psychological and social functioning domains for all participants in the dynamic. The implicated parties - perpetrators, targets, and observers - demonstrate distinct patterns of psychosocial adjustment difficulties. Targets frequently exhibit elevated rates of internalizing behaviors, while perpetrators often display patterns consistent with externalizing difficulties. Notably, bystanders, though not directly involved, frequently report significant psychological distress and moral disturbance.

The intensity of these effects appears amplified during adolescence due to developmental factors including, but not limited to, increased social cognition, identity formation processes and heightened sensitivity to peer evaluation. The convergence of these developmental factors with social dynamics creates a particularly vulnerable period for peer-related psychological distress.

According to Sulejmani and Ziberi (2024), there are four types of bullying: physical bullying, which aims to cause physical harm to another person through aggression, including kicking, hitting, and stealing; verbal bullying, which is more connected to teasing and insults, includes the use of offensive language and threats; relational bullying, which occurs covertly and is mainly characterized by social exclusion, which can trigger feelings of loneliness and emptiness in children (Ang et al., 2018); and finally, indirect bullying, which is associated with rumors and “gossip.” There is also another type of bullying that has recently been the subject of many studies and occurs through the internet: cyberbullying (Aisya, 2024). In this case, aggression happens through technology instead of direct contact with the person. That said, bullying is divided into three major groups: physical, psychological, and sexual, and in our study, we will only address the first two.

Bullying in the school context represents a risk as it influences children’s health and safety. According to Zhang (2024), it plays a significant role in increasing depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation in adolescents. When an individual is victimized, there can be repercussions at the individual level and on their well-being, or if it occurs among peers in a school, it may affect the school environment, thus impacting the mental well-being of the peer group. In this way, victimization can be seen as an “environmental threat.”

Bullies like to be the center of attention and obtain their status through intimidation, humiliation, and aggression. They are typically intelligent children, much more socially integrated than their victims (Simon et al., 2017), and show more externalization problems. According to the literature, a factor associated with these types of problems is high levels of self-esteem (Ang et al., 2018). Abuse of power, intimidation, and arrogance are some strategies bullies adopt to impose their authority and maintain total dominance over their victims.

Victims find themselves in vulnerable situations, feel different from others, are afraid, and often do not ask for help. They are more susceptible to developing mental illness, their academic performance decreases, and they typically feel depressed, anxious, and lonely, have high stress levels (Graham, 2016), and show indicators of self-blame and low self-esteem. The interpretation of why the victim is in that situation often initiates this discomfort and leads the individual to self-question, “Why me?” They may blame themselves for what happened (Graham, 2016). Studies show that bullying produces consequences in terms of self-esteem and overall life satisfaction of victims.

Bullying dynamics extend beyond aggressors and victims to include bystanders, who play critical roles in either reinforcing or mitigating bullying behavior. Recent studies highlight that bystanders often refrain from intervening due to fear of becoming victims themselves or a lack of perceived obligation to assist the victim (Pečjak et al., 2024). The environment surrounding bullying influences bystander behavior, with factors such as social status, moral disengagement, and peer support shaping their responses (Pečjak et al., 2024).

Bystanders can have different roles and influences. For example, they can be Active vs. Passive. In other words, they can be categorized as active reinforcers, defenders, or passive observers, with their roles influenced by their social context and relationships (Pečjak et al., 2024). Fear and Blame can also play a role. Many bystanders avoid intervention because they fear retaliation or believe victims are responsible for their plight.

Being exposed to bullying practices can have a psychological impact. There is a mental health correlation between being active and being proactive. Negative bystander behavior is linked to mental health issues, while positive actions can mitigate these effects, emphasizing the need for supportive environments (Wang et al., 2024). However, when they manifest empathy and make emergency evaluations, studies show that bystanders are more likely to intervene when they perceive an emergency, highlighting the importance of fostering empathy and social bonds among peers (Han, 2024). On the other hand, some argue that bystander inaction can stem from learned helplessness in environments where bullying is normalized, suggesting a need for systemic change to empower bystanders to act.

The main factor that enables bullying is differences, whether at the physical and mental level, being part of a minority group, suffering from obesity, or having a sexual orientation different from what is considered “normal.” Everything that deviates from the standard established by society and culture itself can be a risk factor (Graham, 2016). Studies show that regarding ethnicity, the majority group tends to develop bullying behaviors towards the minority group due to fear of losing social dominance and, consequently, acting aggressively to maintain the social hierarchy (Ang et al., 2018). This type of bullying is typically practiced by a dominant ethnic group against a minority group that is disadvantaged in numbers within the school context; however, there are also cases where bullying occurs within the dominant group. In these situations, the consequences for mental health are much more negative because even though the person belongs to the majority group, they deviate from the norm, which tends to lead to self-blame and a constant feeling of discomfort (Graham, 2016).

According to research findings, more boys admit to bullying tendencies than girls, which can be explained by the type of bullying adopted. Since boys typically engage in physical aggression, it is more easily detected compared to the type of bullying carried out by girls, which is more relational. One explanation for boys adopting more physical bullying relates to society’s stereotypes about boys, as they are viewed as more “playful, impulsive, and aggressive” while girls are seen as more “passive, calm, and diplomatic” (Ang et al., 2018).

Given that self-esteem is a psychological indicator of health and well-being, various studies highlight that bullies, victims, and students who do not engage in bullying show variations in self-esteem levels. Self-esteem can be defined as people’s subjective perception of themselves (Ang et al., 2018), the evaluation and value each person holds of themselves being something that motivates us to achieve our goals.

The impact of self-esteem on people’s lives extends far beyond what was initially thought. When Sharma and Agarwala (2015) began exploring this topic, they encountered a complex web of personal evaluations oscillating between positive and negative. Not coincidentally, Ang et al.(2018) had already warned about this element’s crucial role in our psychological survival. Orth and Robins (2022) argued that people with solid self-esteem better cope with depression and anxiety and develop more effective strategies for dealing with daily adversities. In turn, when individuals evaluate themselves positively, they develop a kind of natural shield against stress. On the other hand - particularly concerning - when self-evaluation leans toward the negative, people become more vulnerable to all kinds of problems. Personal experiences, feedback from others, and achievements shape this self-esteem over time.

People with high self-esteem tend to value their personal needs more, have a greater desire for control and defensive mechanisms, and thus seek to improve their self-esteem and achieve proposed goals, which, when negatively developed, may lead to aggressive behaviors. In this case, a high level of self-esteem may be associated with a greater tendency to trigger bullying behaviors toward other individuals (Ang et al., 2018). Low levels of self-esteem can be considered a risk factor since they have been linked to aggressive, antisocial behaviors and depression (Wang et al., 2018) but have also been associated with poor academic performance and behavioral and psychological problems (Sharma & Agarwala, 2015).

Research on bullying victimization reveals significant sex differences, highlighting distinct patterns and predictors among adolescents. In Benin, the prevalence of bullying victimization was found to be higher among females (44.6%) compared to males (40.1%), with specific risk factors such as physical attacks and suicidal ideation being more pronounced in females (Gbordzoe et al., 2024). Additionally, a multi-informant study indicated that dysfunctional personality traits, such as impulsivity in males and deceitfulness in females, serve as predictors of bullying and victimization, emphasizing the role of contextual factors like peer relationships (Borroni et al., 2024). In China, sex-specific profiles of bullying involvement were identified, with severe bully victims predominantly being boys and relational bully victims being girls, suggesting that family dynamics also play a crucial role (Zhou et al., 2024). Furthermore, the long-term effects of childhood bullying victimization on depression were found to be moderated by sex, with females experiencing stronger associations with social isolation and depression in later life (Jiang & Shi, 2024). Lastly, sexually and sex-diverse youth face heightened bullying victimization, which correlates with mental health challenges, further underscoring the need for sex-sensitive interventions.

Students’ educational level significantly influences the prevalence of bullying victimization, as evidenced by various studies. For instance, Ghardallou et al. (2024) found that students who repeated grades were more likely to experience bullying, indicating that academic struggles correlate with victimization risk. Similarly, Vadukapuram et al. (2022) reported that bullied students were more likely to repeat grades and miss school, suggesting that bullying adversely affects academic performance (Vadukapuram et al., 2022). Overstreet et al. highlighted that perceptions of unfairness in school environments exacerbate victimization, particularly among high school students, linking educational context to bullying experiences (Overstreet et al., 2022). Furthermore, Pitsia and Mazzone (2021) emphasized that individual factors, including parental education, play a role in bullying dynamics, with higher educational levels potentially offering protective benefits against victimization. Collectively, these findings underscore the complex interplay between educational levels and bullying, necessitating targeted interventions in schools.

Various theories attempt to explain the reasons behind bullying behaviors. One such theory is the “Aggression Compensation Model,” which states that bullying is driven by the low self-esteem of those who practice it. According to this model, bullying is simply a reaction against the self-perceived weaknesses and failures of the “aggressor” (Simon et al., 2017). Although several authors accept this model, Simon et al. (2017) discovered through their studies that the relationship between self-esteem and bullying is complex. Some studies support the hypothetical link between low self-esteem and bullying/aggression, while others found the opposite. A meta-analysis of 152 studies supported the link between low self-esteem and bullying, although the overall effect size was not significant (r 2 = .005). Based on these findings, Simon et al. (2017) proposed a “Revised Compensation Model.” In the new version, bullying is still seen as a type of compensation, but what drives intimidation and aggression is not low self-esteem itself but rather a broader tendency toward a defensive personality, that is a defensive personality structure. As a theoretical construct, defensive personality can be measured in various ways, including characteristics such as defensive egotism, narcissism, and high explicit self-esteem that masks low implicit self-esteem.

This model can be better analyzed in studies conducted with eighth-grade adolescents, where results showed a significant correlation between defensive egotism and bullying and no correlation between self-esteem and bullying. Furthermore, years later, this study was replicated with sixth-grade students in Arkansas, and results showed that high-level defensive egotism is significantly associated with bullying, while self-esteem and bullying were not related (Simon et al., 2017).

Regarding the relationship between self-esteem and bullying, analysis of the collected literature shows that results demonstrate a significant negative relationship between self-esteem and bullying perpetuation, showing that the relationship between these two concepts is weak or even null. Studies have shown that increases in self-esteem are associated with a decrease in being a victim of bullying, as individuals have greater and better capabilities to deal with these situations (Simon et al., 2017).

The present study aims to analyze the influence of bullying behaviors on adolescents’ self-esteem. Specifically, it seeks to: 1) verify if there is a significant relationship between bullying behaviors and self-esteem in adolescents; 2) verify if there are significant differences between the dependent variables “Self-esteem,” “bullying-victim,” and “bullying-aggressor” and the independent variables “sex” and “education level,” and what these differences are; 3) verify if there are differences in the variables “self-esteem,” “bullying-victim,” “bullying-aggressor,” “psychological bullying,” and “physical bullying” according to sex.

Methods

This study is observational, quantitative, and cross-sectional, as data were collected at a single moment.

Sample

The study included 303 adolescents from a secondary school in the northern part of the country, of which 158 were female, and 144 were male, aged between 12 and 20 years (M = 14.54; SD = 1.86). Participants were adolescents enrolled in secondary school, with guardian consent. Those with disabilities that could hinder questionnaire completion were excluded.

Instruments

To achieve our study objectives, we used three instruments: 1- The sociodemographic questionnaire was used to obtain information about the individual, such as sex, age, and family structure. 2 - Vasconcelos-Raposo et al. (2011) translated and adapted the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale. This scale aims to analyze both positive and negative considerations that individuals have about their characteristics. The items are presented on a Likert-type scale, with ten items: five are positively oriented, and the other five are negatively oriented. Regarding the psychometric qualities of this scale’s validation, they proved to be very good, as the global internal consistency value of the scale is high (α = .845). 3 - Physical and Psychological Bullying Questionnaire, translated and adapted by Vasconcelos-Raposo, is a self-report measure that assesses bullying levels. This questionnaire is subdivided into two parts, with the first part corresponding to behaviors related to bullying aggressors and the second to behaviors related to victims. Items are presented on a Likert-type scale, and each part of the questionnaire is subdivided into questions related to physical and psychological bullying. Due to technological limitations, scale validation was not possible. However, the adaptation of this scale for the study population shows good psychometric properties, with good internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s α value of .806 for the victims’ questionnaire and .715 for the aggressors.

Procedures

Initially, we sought to obtain school authorization for this study, and once obtained, informed consent forms were distributed to students, ensuring data confidentiality and anonymity. Following guardian authorization for questionnaire completion, data collection was conducted, with all participants included in the study and no dropouts recorded. Students were adequately informed about the questionnaires’ subject matter, and a welcoming environment was provided to answer questions honestly and consciously, making them feel comfortable to ask any questions that might arise. Questionnaire administration took approximately 15-20 minutes, including both actual administration and participant preparation. After collection, questionnaires were numbered and entered into an SPSS 25 (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) database for statistical analysis. Initially, descriptive statistics were calculated, and to help decide which procedures to use subsequently, we referred to Skewness and Kurtosis values. Considering that the values obtained were between -1 and 1, parametric statistics were chosen. Thus, assuming normal data distribution, we used MANOVA to compare the three independent variables (sex, education level, and family structure), and statistical effects were also calculated. Subsequently, a Student’s T-Test was performed to analyze the relationship between sex and dependent variables (self-esteem, bullying victim, bullying-aggressor, physical bullying, and psychological bullying). Finally, a Pearson correlation was performed between self-esteem and bullying variables (aggressors and victims). The significance level was maintained at 5%, p = .05.

Statistical Analysis

SPSS software (IBM SPSS Statistics, version 28) was used for statistical data treatment. Initially, descriptive statistics and normality measures were analyzed. The internal consistency degree of the study variables’ dimensions was calculated using Cronbach’s alpha to understand if the instrument is reliable for the collected sample. Thus, Cronbach’s alpha values above .90 indicate very good internal consistency, between .80 and .90 good, between .70 and .80 satisfactory, and below .60 low internal consistency. To verify if there was any relationship between dependent variables (self-esteem and bullying) and independent variables (sex, education level, family structure), we performed MANOVA, and statistical effects were also calculated. After MANOVA, we performed ANOVA to understand which dependent variables showed differences.

Additionally, we performed t-tests for independent samples to verify significant differences between sex and different dependent variables (self-esteem, physical bullying, psychological bullying, bullying aggressors, and bullying victims). Finally, to understand if there was a correlation between the two dependent variables (self-esteem vs. sex), we performed a Pearson correlation. The significance level was maintained at 5%.

Results

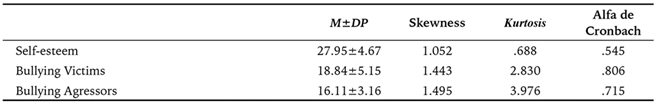

The sample consisted of 303 adolescents (158 females and 144 males) aged between 12 and 20 years (M = 14.54, SD = 1.86). Descriptive analysis revealed a mean self-esteem score of 27.95 (SD = 4.67), with bullying-victim behaviors averaging 18.84 (SD = 5.15) and bullying-aggressor behaviors averaging 16.11 (SD = 3.16). The reliability of the instruments showed acceptable internal consistency for bullying-victim (α = .806) and bullying-aggressor (α = .715) measures, while the self-esteem measure showed lower reliability (α = .545).

Regarding the descriptive analysis, self-esteem obtained a mean value of 27.95, bullying in victims about 18.84, and aggressors 16.11. The first point we can understand through this data is that in our sample, there were more individuals with typical victim behaviors than aggressors. (Table 1)

Multivariate analysis

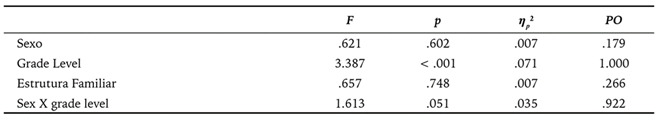

A multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was conducted to examine the effect of sex, grade level, and family structure on self-esteem, bullying-victim behaviors, and bullying-aggressor behaviors. Significant differences were found for grade level (F = 3.387, p < .001, η p ² = .071), with a moderate effect size. However, no significant differences were observed for sex (F = .621, p = .602) or family structure (F = .657, p = .748). The interaction between sexes and grade level was also not significant (F = 1.613, p = .051).

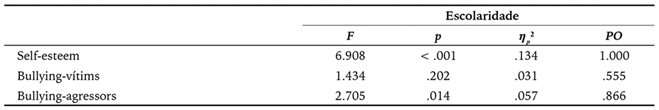

Further univariate tests revealed significant effects of grade level on self-esteem (F = 6.908, p < .001, η p ² = .134) and bullying-aggressor behaviors (F = 2.705, p = .014, η p ²= .057), but no significant differences were found for bullying-victim behaviors (F = 1.434, p = .202). (Table 2)

Table 2: Multivariate analysis of variance: main effects and interactions.

(F = estatística F ; P = valor de prova; η p ² = eta parcial; PO = poder observado)

Furthermore, we could verify statistically significant differences in the bullying-aggressors variable (F = 2.705; p = .014; PO = .866), with a high observed power value and a moderate effect size (η p ² = .057). However, no statistically significant differences were found for the bullying-victims variable.(Table 3)

Table 3: Univariate effects of education level on self-esteem and bullying behaviors: between-subjects test results.

(F = estatística F ; P = valor de prova; η p ² = eta parcial; PO = poder observado)

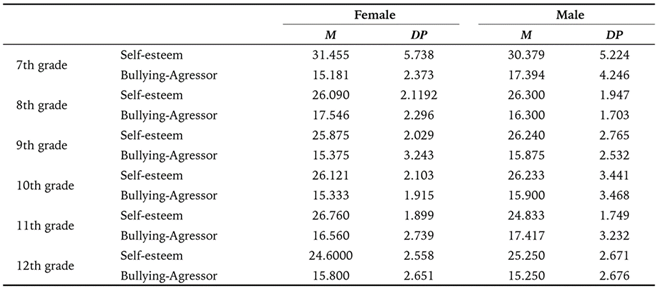

Regarding the descriptive statistics for these differences (Table 4), we found that self-esteem levels were highest during the 7th grade for both sexes. As for Bullying Aggressor levels, we found that in males, they are highest in 7th and 11th grades, while in females, they peak in 8th and 11th grades.

Table 4: Mean scores and standard deviations of self-esteem and bullying-aggressor behaviors by sex and grade level.

Sex differences

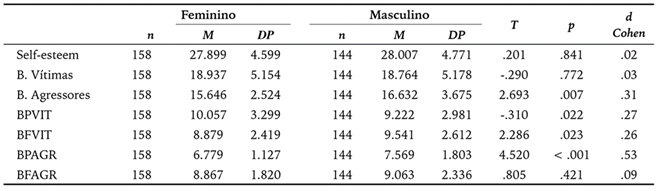

Independent samples t-tests were performed to analyze sex differences in self-esteem, bullying behaviors, and their subtypes (Table 5). No significant difference was observed in self-esteem between males (M = 28.01, SD = 4.77) and females (M = 27.90, SD = 4.60; t = .201, p = .841).

Regarding bullying-aggressor behaviors, males scored significantly higher (M = 16.63, SD = 3.68) than females (M = 15.65, SD = 2.52; t = 2.693, p = .007). For psychological bullying victimization, females scored higher (M = 10.06, SD = 3.30) than males (M = 9.22, SD = 2.98; t = -2.310, p = .022), whereas males reported higher physical victimization (M = 9.54, SD = 2.61) than females (M = 8.88, SD = 2.42; t = 2.286, p = .023). Psychological bullying-aggressor behaviors were also found to be higher in males (M = 7.57, SD = 1.80) than females (M = 6.78, SD = 1.13; t = 4.520, p < .001). No significant sex differences were found for physical bullying-aggressor behaviors or bullying-victim behaviors overall. Given this, we consider, in all previously mentioned cases and according to the t-Test analysis, a strong effect for the sex variable.

Table 5: Teste-t para avaliar a relação entre a variável sexo e as variáveis dependentes.

BPVIT - Psychological bullying victims; BFVIT - Physical bullying victims; BPAGR - Psychological bullying aggressors, BFAGR - Physical bullying aggressors

Correlational Analysis

Pearson correlations were conducted to examine the relationships between self-esteem, bullying-victim behaviors, and bullying-aggressor behaviors. A weak positive correlation was found between self-esteem and bullying-victim behaviors (r 2 = .22, p < .001), suggesting that higher self-esteem is associated with higher victimization reports. Similarly, a weak but significant positive correlation was found between self-esteem and bullying-aggressor behaviors (r 2 = .18, p = .178). Finally, a significant positive correlation was observed between bullying-victim and bullying-aggressor behaviors (r 2 = .28, p < .001), indicating that individuals who displayed victim behaviors also reported higher levels of aggressor behaviors.

Discussion

Bullying is an aggressive behavior carried out with the intent to harm someone’s well-being (physical, social, and emotional). Its main characteristics relate to intentional behavior and persistence and are based on a power imbalance (Espelage & Hong, 2019). Furthermore, it has been shown to be very frequent across various ages, especially during adolescence (Graham, 2016).

Given this, and to meet our first specific objective, we began by verifying if there were differences in the independent variables of sex and education level. The results showed that only the education level variable presented differences. In this case, as we can see in the results, this difference shows a moderate effect but has a high observed power. Therefore, we proceeded with the Tests of Between-Subjects Effects to understand in which direction these differences occurred, finding that only self-esteem and bullying behavior of aggressors showed significant differences for education level.

According to the descriptive analysis conducted with MANOVA, we could verify that individuals showed higher levels of self-esteem in 7th grade regardless of sex. Self-esteem levels were lowest in the 12th grade for females, while for males, it was in the 11th grade. Regarding bullying aggressor behaviors, males showed higher values in the 7th and 11th grades, while females showed higher values in the 8th and 11th grades.

Taking all these results into account, we found that it was in 7th grade that individuals showed both higher levels of self-esteem and higher levels of aggressor behaviors. Therefore, we can consider that in the present study, aggressor behaviors are motivated by high levels of self-esteem, which aligns with what the literature says. Aggressors like to be the center of attention and obtain their status through intimidation, humiliation, and aggression. A factor associated with this type of problem is high levels of self-esteem (Ang et al., 2018). Pitisa and Manzone (2024) obtained similar results since they found that educational level influences bullying victimization, with variations observed between fourth- and eighth-grade students.

According to previous studies, there is a higher probability of physical bullying behaviors occurring among males than females, meaning males are more prone to resort to physical aggression. The justification for this fact stems from the existence of stereotypes that society creates regarding boys and girls (Ang et al., 2018). This evidence was verified through the results obtained from the T-Test (second specific objective, to verify if there are differences in the variables “self-esteem,” “bullying-victim,” “bullying-aggressor,” “psychological bullying,” and “physical bullying” according to sex), where female adolescents showed statistically lower values compared to male adolescents.

Regarding psychological bullying victim behaviors, there was a significant difference between sexes, with girls showing higher values compared to boys. The opposite was found when victim behaviors were associated with physical bullying, where females showed lower values than males. Previous studies revealed that boys more adopt physical bullying as they are more impulsive and aggressive than girls (Ang et al., 2018).

Concerning aggressor behaviors associated with psychological bullying, lower values were found in females compared to males, meaning that according to our results, girls do not exhibit as many psychological bullying behaviors as boys. Regarding the variables “self-esteem,” “Bullying victims” and “Physical bullying aggressors,” no statistically significant differences were found for sex.

To address the third specific objective, verifying if there is a significant relationship between bullying behaviors and self-esteem in adolescents, we analyzed the Pearson correlation between the two dependent variables (self-esteem and bullying) and found a significant relationship between self-esteem and bullying victim behavior. According to our results, when self-esteem values increase, there is a greater propensity for individuals to experience bullying and vice versa. In other words, these results indicate that victims have high self-esteem values, which contradicts our literature that states victims are in vulnerable situations, feel different from others, are fearful, and often do not seek help, showing indicators of self-blame and low self-esteem. Furthermore, studies by Simon et al. (2017) demonstrated that the relationship between these two concepts is weak or even null, and as self-esteem increases, behaviors associated with being a bullying victim decrease.

However, despite our results showing a significant positive correlation between these two concepts, we consider this might be related to students possibly not responding most sincerely to the bullying questionnaire. We noted that during questionnaire completion, students often considered aggressive behaviors as unintentional and, according to them, “just playing around,” thus potentially providing inadequate responses to experienced situations. Additionally, the correlation showed a weak effect, which could align with our literature, where no significant relationship between these concepts is found.

When analyzing the results regarding the relationship between self-esteem and Bullying-aggressor, there is also a statistically significant positive correlation between these concepts. These results indicate that low self-esteem values lead to fewer aggressive behaviors, which contradicts the literature stating that low self-esteem levels can be considered a risk factor since they have been related to aggressive and antisocial behaviors (Wang et al., 2018). Moreover, a meta-analysis of 152 studies supported the link between low self-esteem and bullying, although the overall effect size was small (Simon et al., 2017).

Finally, based on the obtained results, we consider there exists a significant relationship between bullying-victim and bullying-aggressor, leading us to assume that behaviors associated with being a victim will increase aggressive behaviors. As we can verify in the literature, victims tend to have diminished self-esteem, and these low self-esteem levels have been related to more aggressive behaviors. In summary, bullying is a social behavior that has been affecting many individuals, reaching its peak during adolescence, a phase when more social relationships begin to form and peer approval becomes extremely important. Sometimes, what occurs is constant disapproval from either an individual or a group of individuals who intentionally, persistently, and in a situation of power imbalance affect the individual’s mental well-being. These bullying behaviors carry many negative consequences, leading individuals to believe they have no worth and, in extreme cases, may even lead to suicide. Thus, although some prevention programs for these behaviors are beginning to exist and be implemented in educational institutions, we believe that in the future, more resources should be made available in schools so that anyone present there (teachers, students, and staff) is capable and has sufficient information to deal with bullying situations/behaviors.

Conclusion

The present study examined the relationships between self-esteem, bullying behaviors, and various demographic factors among students from 7th to 12th grade. Our findings revealed several significant differences across grade levels, with self-esteem reaching its highest levels in the 7th grade before progressively declining in subsequent years. Bullying-aggressor behaviors also showed notable variation across grade levels, indicating developmental shifts in the manifestation of aggression.

Sex differences were evident, with males exhibiting higher levels of both physical and psychological aggressor behaviors, while females were more likely to report experiencing psychological victimization. These findings underscore the distinct ways in which bullying behaviors and experiences manifest between sexes.

Contrary to previous research, a significant overlap was identified between bullying-victim and bullying-aggressor roles, highlighting a complex and dynamic interplay. This suggests that individuals may simultaneously occupy both roles, further emphasizing the interconnected nature of bullying behaviors.

These results highlight the complexity of the interplay between grade level, sex, self-esteem, and bullying behaviors. The need for targeted interventions at specific grade levels and sex-sensitive approaches to bullying prevention is also emphasized by the results. Future research should focus on understanding the temporal dynamics of these relationships and developing more effective, context-specific intervention strategies.