Approaching Complexity Through Feminist Epistemology

In the early hours of July 7, 2016, in Pamplona, Spain, five young men took an intoxicated young woman into the lobby of a building, gang-raped her, and took photos and videos of the event. The case became known as "La Manada" (the wolf pack), the self-imposed nickname the five rapists used in a WhatsApp group to brag about sexual harassment of women and other delinquent behaviour. The case drew intense public scrutiny, and the court process received ample media coverage from the beginning and triggering self-criticism from actors in Spain, including judges, politicians, intellectuals, and activists. In April 2018, the Provincial Court of Navarra found the five assailants guilty of the lesser crime of sexual abuse, implying that the gang rape had not been an act of violence. Immediately, thousands of people brought it to the streets and digital spaces to show their support for the victim and their rage against what they considered patriarchal justice. For months, banners, placards and chants flooded the streets, and Twitter was inundated with hashtags such as #HermanaYoSíTeCreo (#SisterIDoBelieveYou) and #JusticiaPatriarcal (#PatriarchalJustice). The enormous public outcry reached the European Parliament and the United Nations and propelled a revision of the Spanish Penal Code. After 1 year, the Spanish Supreme Court found the five assailants guilty of rape and sentenced each of them to 15 years in prison. Furthermore, in October 2021, the House of Commons voted in favour of the Organic Law on the Comprehensive Guarantee of Sexual Freedom, colloquially known as the "yes-is-yes" law.

The digital visual artefacts under consideration are complex in themselves. They have been shared alongside texts (hashtags and otherwise), many images also featured text (mostly hashtags), many are very similar, many are repetitions, all of them were publicly shared, some are traces of offline demonstrations, and some were designed for virtual protests specifically. These collective processes of remix and convergence generated visualisations, imaginations, and gazes that became common and were shared by a "virtual" community of sisterhood, amplifying the social movement itself and supporting the emergence of affective publics (Papacharissi, 2015).

Sharing images and reacting to them are central and easy-to-do actions in social media. Both the sharing and the reacting mobilise affect, thereby giving rise to shared affective identities and meanings (Nikunen, 2019; Wetherell, 2012). In fact, the act of sharing images online closely resembles what Assmann and Czaplicka (1995) called "concretion of identity" (p. 128). This process consists in an organisation and objectivisation of everyday memory that allows a group to reproduce its identity (Assmann & Czaplicka, 1995) strongly supported by objects (e.g., posters, banners, social media posts). The communicative memory and the remembering frame (Erinnerungsrahmen) are materialised in communicative objects, and formative and normative impulses are derived from this process. In other words, after a process of concretion of identity, members of a group possess tacit knowledge that allows them to participate in common actions. We believe that communicative objects function as containers of memory and affect, which may be animated to a varying degree when the object is encountered with and embodied, emplaced, and affective understanding, such as the one provided by engaged Twitter users around #HermanaYoSíTeCreo.

In order to account for the complexity of the visual artefacts linked to #HermanaYoSíTeCreo, we developed an ethnographic sensibility towards the corpus, which pragmatically speaking, meant working through dialogue and repetition, as well as incorporating a constant process of self-reflection on researchers' positionalities and embodiments. This research approach is rooted in feminist principles of exploring and disrupting customary modes of knowledge production, foremost by (a) situating knowledge through a place, body and power (Collins, 1990; Haraway, 1988; Harding, 1993; Hekman, 1997); (b) by acknowledging and granting the uncertainty of experience to be present during the research process (Bell & Bell, 2012; Squire, 1995); (c) by alternating contextualisation and specificity in the analysis (Bach, 2007); and (d) by allowing ourselves to get lost in the data (Lather, 2007).

We shall note here that while Elisa lived the case study in her bones and experienced both digital and analogue crowds of protest first-hand, and Silvia managed to catch the tail-end of the movement when she returned to Spain in 2019, Patricia observed the entire process from a distance in the United Kingdom. It was only through dialogue with Elisa and Silvia that Patricia also came to understand these digital visual artefacts as part of larger affective practices (Wetherell, 2012) and as catalysts for a wide process of feminist education of the masses and societal transformation via the new "yes-is-yes" law. This process also demonstrates the illuminating autobiographical traces we, researchers, leave on our investigations (Valles Martínez, 2009, p. 106) and highlights the need to understand research as collaborative work in all its stages. We believe that only through collaboration and dialogue, intersubjective and tacit knowledge come to the fore, which are needed to overcome the positivist trend of data-driven visual digital analysis. Importantly, the collaborative work modus we propose includes careful attention and integration of mutual misunderstandings and failures in communication, as these often give rise to a productive "verbalization and transformation of implicit experience as and into explicit knowledge" (Loenhoff, 2011, p. 62). Approaching the 696 visual artefacts collaboratively has also allowed regard to the implicit rules of the perceptual, representational and epistemological codes (Serrano Pascual & Zurdo Alaguero, 2010, p. 222) present in the current audio-visual culture of hashtag feminism in Spain, and of the emerging hashtag machismo also.

Our operationalisation of affect departs from a working definition of affect as the social, the material and the psychological wrapped into a force that peaks and lows (Ahmed, 2004). It attempts to be transversal in that we understand affect as a force that exists both in relation to a sociocultural context and independently from it. It incorporates attention to affective practices (Wetherell, 2012) and affective atmospheres (Anderson, 2009). Affective practices refer to how emotions and affects impact political action while acknowledging the role of cultural norms, social structures and technology in shaping said practices. Affective practices are where human emotion is foregrounded and key to creating and maintaining a sense of collective belonging. Since affective practices emerge and consolidate within concrete socio-technical (or socio-material) formations, it is important to consider the atmospheres where those processes take place. Thus, in addition to considering tweets and visual digital artefacts, we interviewed feminist activists involved in the “La Manada” protest.

Furthermore, our visual analysis has prioritised the contextual conditions of the dissemination and reception of these images. In a further step, we have considered the potential of these images to mobilise affect and leave deep traces at individual and collective levels (Sontag, 2003). In social media, particular affordances will be activated for people, non-human actors and discourse to come together and generate collective feelings, employing bodies, images and texts to carry an affective load (Nikunen et al., 2021, p. 169). And while it is important to pay attention to the particular affordances of social media platforms, as those help the formation and continuity of communities of practice — for better or for worse — it is paramount to abstract affective practices from platforms, that is, our research must be specific and broad enough to a socio-technological context in constant change (Lobinger & Schreiber, 2017, p. 17)

By prioritising the contextual conditions of the circulation of digital visual artefacts in our analysis, we seek to shed light on the role of visual affective practices in forming social and political belonging. In doing so, we build on Jenzen et al. (2020) investigation of the cultural and symbolic value of communicative processes in social media. Working with Twitter and hashtag ethnography has allowed us to look at a timeline of group objectification, so to say, at a register of visual affective practices related to this process. Furthermore, in considering the conditions under which the hashtag feminism of #HermanaYoSíTeCreo developed (Kettrey et al., 2021), we have been able to evidence the effectiveness of this particular movement in dismantling key aspects of misogyny in Spain, foremost reversing the victim-blaming paradigm. We believe that digital communicative practices of protest, such as the one associated with #HermanaYoSíTeCreo, show memory in action, resistance through active involvement, and the formation of a concrete political imaginary.

Collaborative and Embodied Visual Analysis

Here, we report a collaborative visual analysis of 696 digital images based on a triangled analysis that needs at least two researchers: one that has embodied the affective dimension of the social phenomenon under study; and a second researcher that has not but who is familiar with it. All 696 digital images were shared on Twitter with the hashtag #HermanaYoSíTeCreo between May 2018 and August 2020. This task was accelerated by the fact that at this point in the research process, we had already completed a hashtag ethnography of the same hashtag (García-Mingo & Prieto Blanco, 2021). Thus, we manually scrapped the images and analysed them using a combination of digital and analogue tools (e.g., Image Sorter), colour coding, and photo-collaging. It is important to note that this paper could be understood as a sequel of our previous work, as it was only through the previous engagement with the hashtag that we have been able to achieve a thick interpretation of these 696 images. However, this work stands on its own in that it aims to expand the definition of hashtag ethnography proposed by Bonilla and Rose (2015) by (a) arguing for the need to examine digital visual artefacts linked to hashtags; (b) appealing for the need of conducting on-the-ground qualitative research to deepen the insights gained via the analysis of textual/visual artefacts; (c) acknowledging and tracing our own embodied, emplaced, and, affective relationship to the object of study; and (d) exercising and bringing to light the continuous dialogue, critique, reflection and retrospection feminist research demands.

In the following pages, we will provide a general overview of the data first, followed by a section in which we will delve into concrete moments that galvanised heightened affective intensity — protests related to the Manresa and Arandina cases — and reflect on why others did not.

Images and Hashtags: A Well-Matched Couple

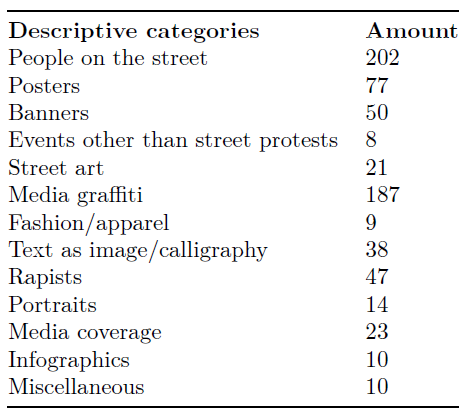

The first step of our engagement with the 696 visual artefacts was to become familiar with them by looking at them individually and sequentially. It is important to note that the results of our hashtag ethnography of #HermanaYoSíTeCreo were in the back of our minds while incessantly browsing through the images. After this, we proceeded to organise the images according to their content. We worked with descriptive categories (see Table 1 below) and realised the saliency of (a) images of offline protests; (b) what we called media graffiti, that is, images designed to be shared on social media as if one were spray painting on an analogue wall; and (3) lens-based images. Furthermore, we noticed the hefty number of repetitions of portraits of the rapists, which we based our previous work on (García-Mingo & Prieto Blanco, 2021). We associated those with synchronised actions of response-ability (Rentschler, 2014) and the frequent transformation of hashtags into aesthetically pleasing pieces of calligraphy, which we believe contributes to the hashtag texture and aims to increase the hashtag spread and visibility.

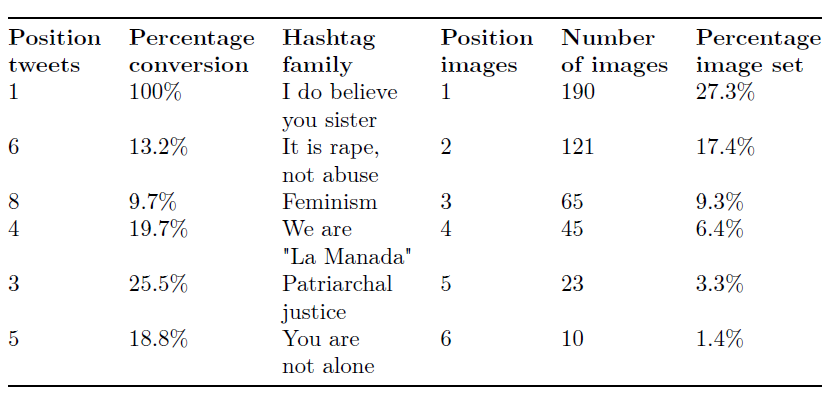

All 696 images had been tagged with #HermanaYoSíTeCreo, but as we browsed through them, we noticed the images themselves featured other hashtags. Therefore, our second step was to find all hashtags featured in the dataset, note down the feature frequency, and identify hashtag resonances. Unsurprisingly, #HermanaYoSíTeCreo was not only the most featured hashtag but also the one with a higher number of family hashtags used alongside (234) and the one related to a higher number of hashtags extraneous to the hashtag family: #SiNoNosMatanNoNosCreeis (#IfTheyDontKillUsYouDontBelieveUs) and diverse variations thereof, #JusticiaParaDiana (#JusticeForDiana); #cuentalo (#SayIt; the Spanish equivalent of #MeToo); and #mirame (#LookAtMe). However, we were surprised by the frequency in which #FueViolacion (#ItWasRape) was featured along another hashtag of the same family, namely 1.58 on average, which we attributed to the development of the protests over time, including the different sentences, and importantly so, the linking of "La Manada" case to subsequent cases of rape and sexual abuse in Spain. A big surprise came when we realised the absence of related hashtags in the case of #LaManada (#TheWolfPack), as that was not the case in the previous hashtag ethnography we carried out (García-Mingo & Prieto Blanco, 2021). We believe this is due to the expanded timeline of this dataset. This step's last substantial finding was the realisation of the force of feminism in each hashtag (except for #LaManada). While in #HermanaYoSíTeCreo and #FueViolacion, the words "feminism" and "feminist" appear sparingly, when it comes to #JusticiaPatriarcal, not only has their presence increased, but it has also evolved into the hashtag #AlertaFeminista (#FeministAlert) and the pair "feminist response" (albeit without the #).

Compared with the most used hashtags in the week of June 21, 2018, which is the period we covered in our previous analysis (García-Mingo & Prieto Blanco, 2021), one gains insights into the endurance of the hashtags. Popular but topical hashtag families "La Manada out of jail", "La Manada free, justice undone", or "letter of the victim" are not present in the image dataset, while versatile ones, "it is rape, not abuse" and "feminism" gain relevance. Interestingly, the word “feminism” featured in 65 images but was not used as a hashtag. Instead, we found a new related hashtag, namely #AlertaFeminista. As our analysis below will highlight, and in line with the findings of our previous work (García-Mingo & Prieto Blanco, 2021), we believe this is evidence of not only the growing sophistication and diversification of the movement but also the long-lasting character of the affective unification achieved via the harmonious — and often synchronised — series of offline and online protests. In other words, the image dataset (Table 2) reveals a sense of belonging that surpasses collective effervescences around topical issues and visualises the formation of a socially widespread feminist consciousness that understands violence against women as a systemic problem.

The extensive presence of hashtags on the image dataset evidences the deep link between offline and online protests. When incorporated into images, the hashtags' intrinsic affordances are rendered void as they become unreadable by social media algorithms. Instead, they are granted a different functionality, namely connecting the offline and online areas of activity and merging protests and protesters in both realms. Another feature that speaks about connecting through difference is the linguistic diversity of the images, which includes texts in Castillian, Basque, Galician, Catalan, English, Asturian, Latin American Spanish, and Arabic. In the next section, we will explore how said connections were established over time and how we believe their endurance demonstrates the resilience of #HermanaYoSíTeCreo as a hashtag and social movement.

Believing the Survivor/Victim: A Modular Yet Integrated Performative Action

Almost three-quarters of the images shared online were lens-based ones, including photographs (364), photographs with overlaid text (80), screenshots (35) and posters featuring photographic content (29). The evidentiary nature of the visual artefacts shared on Twitter is further reinforced by the sheer number of tweeted photographs of offline protest, namely 289 (41.5%), which foremost feature people protesting on the streets, followed by banners and placards. There were also photographs clearly taken at indoor events, such as three images related to the theatre play Jauria, which was developed based on the court transcripts of the “La Manada” case and premiered in April 2019. Another indoor event that generated many shared photographs is a gathering of the spanish Communist Party during the annual fair in Almería, which takes place every late August. In the 2018 edition, the hashtags #HermanaYoSíTeCreo and #NoEsNo (#NoIsNo) were transformed into slogans decorating a purple photo-call frame along with the logo of the political party.

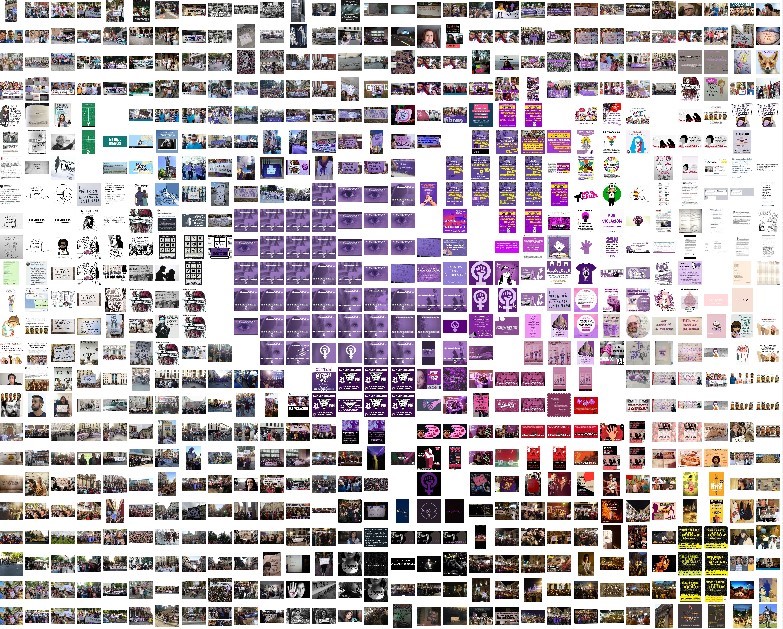

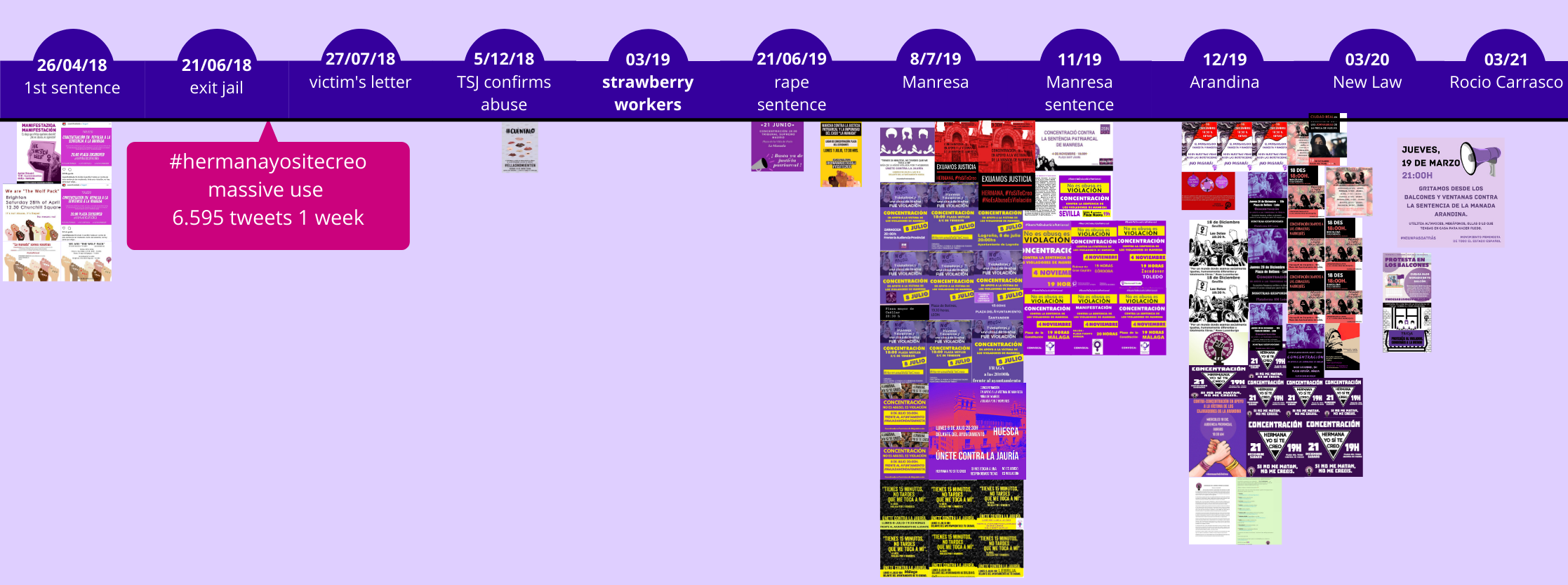

It was at this early stage of the movement, June to September 2018, that purple became the main strategy of the "[p]urposeful visual branding" (Jenzen et al., 2020, p. 420) of visual activism related to the “La Manada” protests. While 93 images entirely or predominantly feature the colour purple, many others contain purple elements, such as banners and placards, which evidence the prevalence of purple online and offline. Furthermore, another substantial group of images feature neighbouring colours to purple, such as magenta, pink and fuchsia in different shades. While Figure 1 and Figure 2 offer an overview and an illustration of the prevalence of the colour purple and neighbouring colours in the entire dataset, Figure 3 (and, to a lesser extent, Figure 4) provide evidence of the growing significance of purple over time, which peaks in July 2019 (Manresa case) and again in December 2019 (Arandina case).

Note. Images retrieved from https://twitter.com/hashtag/HermanaYoS%C3%ADTeCreo between May 1, 2018, and August 31, 2020

Figure 1 The 696 visual artefacts tagged with # HermanaYoSíTeCreo (#SisterIDoBelieveYou) on Twitter between May 2018 and August 2020 and organised by colour

Note. Translations from left to right in the top row: "calm down sister, here is your wolf pack"; "#SisterIDoBelieveYou" and "#IfTheyDontKillUsYouDontBelieveUs"; "July 11, 21:00 Pillars: no sexist attacks! Bull stadium → castle square"; "it was rape. The pack, condemned"; "I believe in you". Translations from left to right in the bottom row: "#SisterIDoBelieveYou"; "campaign against the TSJCyL ruling on the Arandina case: TSJCyL protects the rapist, condemns the minor"; "stop rape culture"; "we want to be alive". Images retrieved from https://twitter.com/hashtag/HermanaYoS%C3%ADTeCreo between May 1, 2018, and August 31, 2020

Figure 2 Illustrative sample of the prevalence of purple in the dataset

Note. Images retrieved from https://twitter.com/hashtag/HermanaYoS%C3%ADTeCreo between May 1, 2018, and August 31, 2020

Figure 3 Photographs of offline protest tagged with #HermanaYoSíTeCreo on Twitter from May 2018 to August 2020

Note. Images retrieved from https://twitter.com/hashtag/HermanaYoS%C3%ADTeCreo between May 1, 2018, and August 31, 2020

Figure 4 Posters of protest tagged with #HermanaYoSíTeCreo on Twitter from DATES

Along with colour, the presence of the feminist fist is quite substantial (featured in 128 images; Figure 5), but we argue it cannot be considered an unmistakable symbol of the #HermanaYoSíTeCreo protests because (a) its use was not widespread nor consistent enough; (b) its most frequent use is linked to logos of feminist organisations, and (c) it shared the spotlight with other symbols such as the extended hand, and a triangle formed holding both hands on the air.

Note. Translations from left to right: "I believe in you"; "Feminist Assembly of Aranda"; "#SisterIdoBelieveYou"; "Friday, June 21 at 10 am. Concentration in the City of Justice: we do believe you! We've had enough of patriarchal justice! Call: Feminist Movement of Valencia". Images retrieved from https://twitter.com/hashtag/HermanaYoS%C3%ADTeCreo between May 1, 2018, and August 31, 2020

Figure 5 Illustrative sample of the presence of different protest symbols in the dataset

We believe that the variety of symbols of protest found in its dataset responds to the fact that the main form of protest was not aesthetic, political acts but performative acts of support and belief in the victim (García-Mingo & Prieto Blanco, 2021, p. 11). Their acts were carried out individually and harmonically, often in synchrony. Therefore, in contrast to the analysis carried out by Jenzen et al. (2020), we believe repetitions need to be regarded in our analysis. By this, we not only mean an exploration of repetitive colours/tonalities, motifs, and hashtags, which provides insights into the branding strategy of the movement, but rather a close look at those images repeated again and again with minor or no modifications.

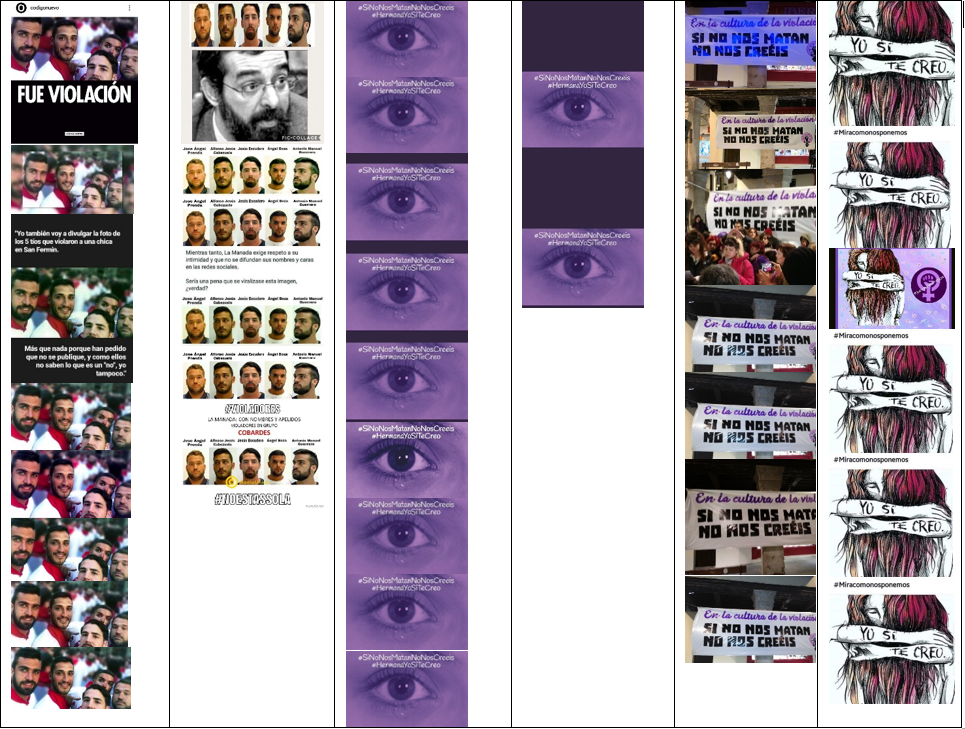

By turning our attention to the repeated use of images, particularly those that are only so slightly modified and shared again, we identify sets of artefacts that encapsulate particularly significant issues for the #HermanaYoSíTeCreo moment and have a certain status within the community. The figure below (Figure 6) contains the most repeated images with some degree of modification. That is, other images were repeated more often but without modification. Why do we emphasise modification? Because intervening in the image signals a greater investment than sharing it alone. Sometimes, as in the case of the images on the first two columns (from the left-hand side), it may also signal a greater digital literacy. More importantly, the slight modifications on these two images of the perpetrators provide further contextualisation and add concrete calls for action that cannot be separated from the visual. For example, by collaging the image of one of the judges with the five portraits of the rapists, the link between them becomes binding; in a similar way as the sisterly hug emerges as an undeniable feminist act when collaged with the feminist fist. Thus, we suggest these slight text-visual modifications contribute to the sophistication of the visual repertoire of #HermanaYoSíTeCreo, and the broadening of the scope of movement. Furthermore, the enormous repetition of images and hashtags can be interpreted as attempts to make the protests' reach, strength, and cohesiveness visible. This last point becomes clearer when considering posters of protest, photographs of protest, and digital artefacts.

Note. Translations of the first column: "it was rape"; "I'm also going to spread the photo of the 5 guys who raped a girl in San Fermin. Mostly because they have asked for it not to be published, and since they don't know what a 'no' is, neither do I". Translations of the second column: "meanwhile, La Manada demands respect for their privacy and that their names and faces are not disseminated on social media. It would be a shame if this image went viral, wouldn't it?"; "#Rapists. La Manada: with names and surnames, gang rapists, cowards#YouAreNotAlone". Translations of the third and fourth columns: "#IfTheyDontKillUsYouDontBelieveUs, #SisterIDoBelieveYou". Translations of the fifth column: "in the rape culture: if they don't kill us you don't believe us". Translations of the sixth column: "I believe in you". Images retrieved from https://twitter.com/hashtag/HermanaYoS%C3%ADTeCreo between May 1, 2018, and August 31, 2020

Figure 6 Most repeated images with slight variations in the dataset

A revealing insight about the number of images depicting indexical bodies in place is that this reverts an earlier observation of virtual communities. In the community we approach here, bodies are not left behind à la Howard Rheingold. On the contrary, they are shown very frequently. The frequency of sharing, liking and re-tweeting these photographs of street protests activates the affordance of indexicality, which transfers a sort of agency to the images by which people start to treat them "as if they were alive" (Lehmuskallio, 2012, p. 164). The photographs bridge the space "between the visible and the invisible" (Edwards, 1997, pp. 58–59), communicating expressively by taking the viewer outside of the frame and revealing what has not been visualised in the image. The evidentiary force of the index both acknowledges and validates experiences portrayed and shared, while the frequent sharing ascribes temporary and contextual value and meaning to the images, which effectively become a form of affective currency (Ahmed, 2004). The affective force of photographs of street protests, of people coming together to raise their voices, lies in their frequency and similarity. They function on a phatic level as they evidence, strengthen and maintain social relations (Rose, 2014, p. 12). Thus, we suggest here that the indexical character of photography demonstrates not just presence but also mediates presence (the physical gathering and the digital gathering merging) and establishes an ethical way to look first described by Azoulay (2005) as the civil contract of photography, that is, as an agreement to represent and to look together.

"The civil contract of photography is not a specific contract made with a specific photographer, but the expression of an agreement over certain rules among users of photography, and the relation of those users and the camera" (Azoulay, 2005, p. 43). Trusting photographs to be pieces of evidence of what "was there" is the result of this agreement. It needs to be enforced at the level of reception also by being involved, by moving "from the addressee position into the addresser's position by addressing it even further, turning it into the beacon of an emergency, a signal of danger or warning, transforming it into an emergency énoncé" (Azoulay, 2005, p. 44). It is about awakening and mobilising a supportive gaze built from and around a community that is aware of and uses its political capacity to hold someone accountable. Unfortunately, establishing such a civil contract is not restricted to feminist activism. On the contrary, as we elaborate below, becoming partial in looking at images of #HermanaYoSíTeCreo also encompasses reactionary heteropatriarchal gazes and may have led to the appropriation of the hashtag (perhaps we shall talk of forceful spoliation instead as their methods and historical points of reference reproduce colonial logics of oppression).

In any case, each and every single photograph shared with #HermanaYoSíTeCreo is an act of partiality, choosing sides, believing what happened, and transforming this belief into something visible, spreadable, and even tangible to some extent. From this perspective, non-lens-based images such as drawings and calligraphy also conform to the civil contract of photography. As Azoulay (2012) remarks, along with the existing photographs, some went missing, some were not taken, some cannot be shown, and some remain invisible but are seen. We suggest that most images shared with #HermanaYoSíTeCreo counteract the invisible images conforming to the victim-blaming paradigm present in the collective memory of Spanish society. We assert this because we have observed a focus on picturing people on the street, banners, and placards, and a strong tendency to picture the perpetrators instead of the victim.

After photographs of street protests, the second most common visual artefact tagged with #HermanaYoSíTeCreo on Twitter are posters of protest (77 out of 696). When we placed them on a timeline (see Figure 3 and Figure 4), discourses associated with affective practices started to become visible, as well as their reach.

The early posters feature references to condemning the sentence of abuse ("it's not abuse, it's aggression”), to the start of the process of reclaiming “la manada” as a symbol of feminist sorority and support (#Estaesnuestramanada [#ThisIsOurWolfPack]); and the systemic gender violence in the Spanish judicial system, such as, "justicia española" (Spanish justice), (in)justicia ([un]justice), #justiciapatriarcal. The condemnation of systemic misogyny in the judicial system becomes more consolidated and sophisticated over time with #justicapatriarcal and #bastayadejusticiapatriarcal (#PatriarchalJusticeEnoughAlready) appearing in more posters and banners (as shown in Figure 3), along with the chant "if they don't kill me, you won't believe me", and in a late step incorporating systemic racism to the condemnation of patriarchal institutions (e.g., #justiciaracista [#racistjustice], "patriarchy and capital, colonial alliance”).

Although protests to condemn the sexual violence suffered by strawberry temp workers in southern Spain took place as early as March 2019, the expanse of #HermanaYoSíTeCreo to colonial and capitalist oppression did not materialise into a massive collective and synchronised action of believing and support until December 2019. There were some street protests in March 2019, but extensive and intensive protests condemning the sexual violence strawberries temp workers suffered only happened 6 months afterwards (as shown in Figure 3).

For context, massive street protests against the sentence of the Arandina case took place only 9 days after the sentence was made public, and the digital reverberations are the strongest we have observed, although closely followed by the Manresa case, also saw offline and online mobilisation happening very fast. It must be noted that both the Manresa and the Arandina cases involved children (14 and 16 years, respectively), while the strawberry temp workers were all adults. More importantly, the latter case demanded an extension of the framework of sorority and believing in the victim to include sexual violence at work and to acknowledge racialised women as sisters.

Furthermore, the use of colour introduced a clear difference between the strawberry temp workers' issues and other cases of sexual violence (Manresa, Arandina, Pozoblanco, "the rapist is you"). Most shared protest posters relating to the former featured pink instead of purple (arguably to strike a resemblance with the colour of strawberries); however, the most shared concerning the latter cases featured purple heavily (see Figure 7 below).

Note. Image retrieved from https://twitter.com/hashtag/HermanaYoS%C3%ADTeCreo between May 1, 2018, and August 31, 2020

Figure 7 Posters of protest for Manresa and Arandina cases and strawberry temp workers

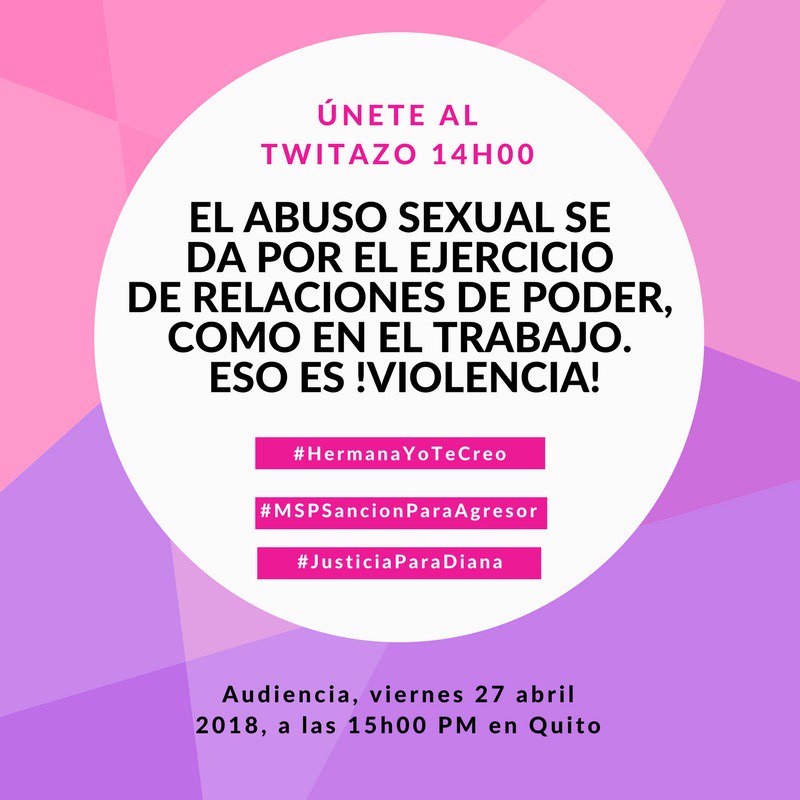

Interestingly, around the same time as protests to support the strawberries temp workers galvanised, purple ribbons in balconies and cars later became symbols of support against sexual violence in Spain, yet when it comes to sexual violence at work, there is little room for purple. The earlier case of #JusticiaParaDiana in Ecuador exemplifies this (see Figure 8). So, as much as it pains us to raise this when critically engaging with the visual artefacts, it becomes clear that there was less social pressure and cohesion once #HermanaYoSíTeCreo was mobilised against racism and labour exploitation in addition to sexual violence. In other words, the affective atmosphere of #HermanaYoSíTeCreo was not ready to incorporate the discourse of anti-colonialism into their visual repertoire.

Note. "Join the Twitazo 2 pm: sexual abuse occurs through the exercise of power relations, such as in the workplace. That's it! Violence! #SisterIDoBelieveYou #MSPSanctionForAggressor #JusticeForDiana. Audience, Friday, April 27 2018, at 3 pm in Quito". Image retrieved from https://twitter.com/hashtag/HermanaYoS%C3%ADTeCreo between May 1, 2018, and August 31, 2020

Figure 8 Poster of online and offline protest regarding #JusticeforDiana 2018

Concluding Thoughts

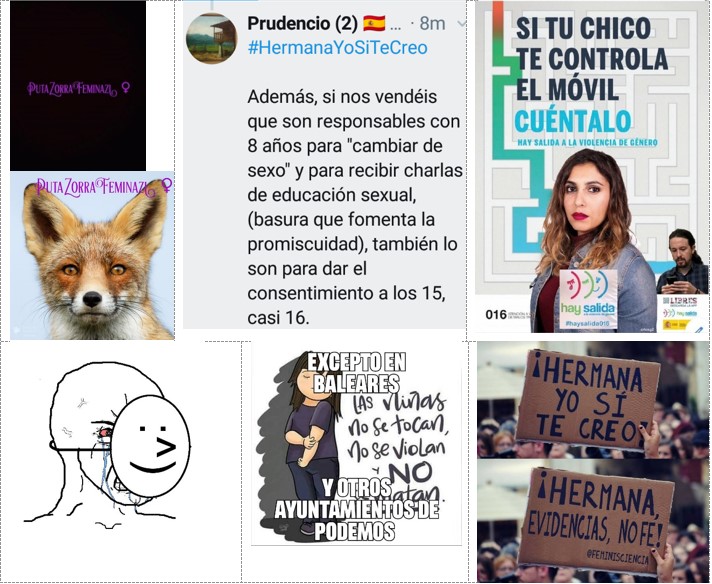

#HermanaYoSíTeCreo reverberated through physical and digital bodies, minds and machines for years (Kunstman, 2012), thereby evidencing a clear perseverance and determination to denounce systemic gender violence in Spain, as well as a growing resilience, strength and reach of feminism in the Spanish state. However, unfortunately, hashtag activism is not restricted to feminism, and the communicative practices used by the #HermanaYoSíTeCreo movement to precipitate a communicative memory and a remembering frame can be — have been and are — used to foster misogyny, discredit the feminist community and establish affective practices of hate. Within our dataset, we found early examples of the appropriation of #HermanaYoSíTeCreo by an anti-feminist movement. Key protest symbols and online actions of the feminist movement have been repurposed to foster affective practices of hate and scorn (see Figure 9). The resulting images spread anger, resentment, and hate along with the ideology of anti-feminism.

Note. Translations from left to right in the top row: "feminazi slut”; "besides, if you sell us that they are responsible at the age of 8 to 'change sex' and to receive sex education talks (rubbish that encourages promiscuity), they are also responsible for giving consent at 15, almost 16"; "if your boyfriend controls your mobile phone, tell it: there is a way out of gender-based violence". Translations from left to right in the bottom row: "except in Balearic and other Podemos municipalities: girls are not touched, raped or killed"; "sister I do believe you. Sister, evidence, not faith". Images retrieved from https://twitter.com/hashtag/HermanaYoS%C3%ADTeCreo between May 1, 2018, and August 31, 2020

Figure 9 Images tagged with #HermanaYoSíTeCreo clearly confirm the anti-feminist movement's ideological work. Note the presence of purple, the original hashtag, and feminism, as well as clear references to the left political party Podemos

The current research of García-Mingo et al. (2022) explores the inner workings of the Spanish manosphere, a growing online anti-feminist movement that fights for the recognition of men's rights and negates the existence of gender-based violence. In the empirical work they have carried out, young Spanish men have often referred to "those of #HermanaYoSíTeCreo" in a clear derogatory way, partially because they firmly believe that gender-based violence is an ideological invention, a hoax.

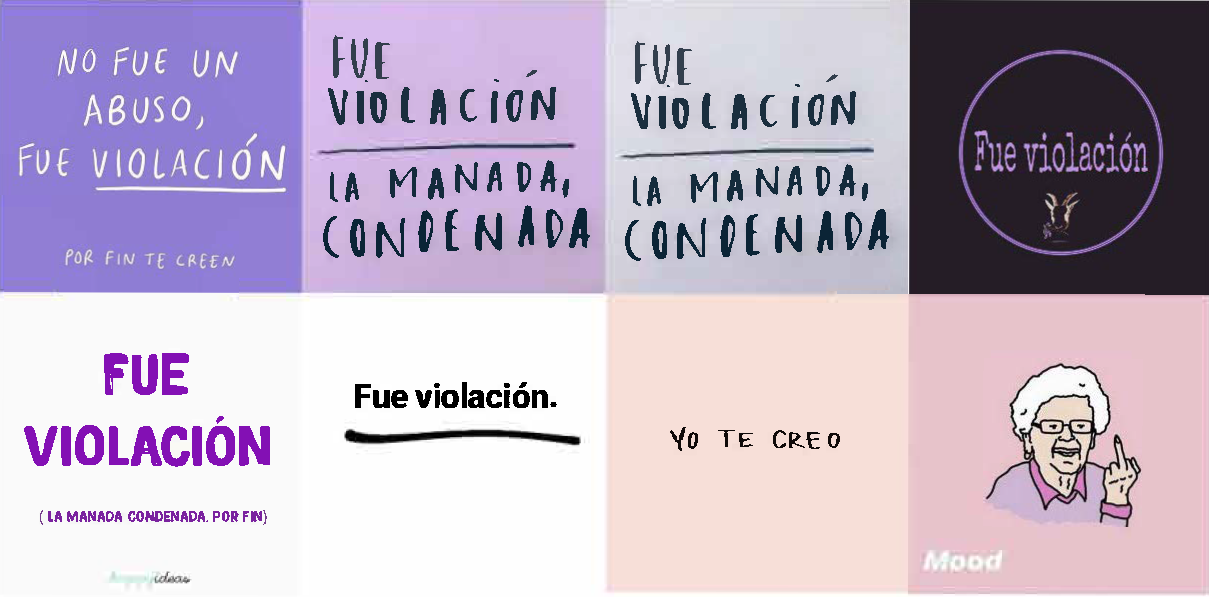

This work discrediting and scorning the #HermanaYoSíTeCreo also softened or depoliticised the movement, translating into a change in the visual branding mostly through colour. The feminist force associated with dark purple softens to lighter shades of purple and pink, and the calligraphy grains importance (Figure 10). We have called this process instagramatization to signal the prevalence of aesthetics over the rest.

Note. Translations from left to right in the top row: "it was not abuse, it was rape"; "it was rape. The pack, condemned"; "it was rape". Translations from left to right in the bottom row: "it was rape (the pack condemned, at last)"; "it was rape". Images retrieved from https://twitter.com/hashtag/HermanaYoS%C3%ADTeCreo between May 1, 2018, and August 31, 2020

Figure 10 Illustrative sample of the instagramatization of #HermanaYoSíTeCreo

In short, hashtags are easily appropriated, and #HermanaYoSíTeCreo is no exception. Affective practices are powerful in fostering a sense of collective identity and belonging, but they can be used for any ideological work. The same comment can be made about social media infrastructures. It is important to remark that the loose policies of most platforms, mainly relying on self-reporting and the avoidance of curtailing any expression a priori, are failing to serve the needs of a safe and balanced public arena. While it is hard to imagine people suffocating with love and sorority, online hate and abuse have very real and significant consequences.

texto em

texto em