Introduction

Among numerous actors searching for their place on the political stage and competing for the most valuable reward: policy influence, think tanks stand out by their proclaimed independence from other actors and production of policy relevant knowledge through research (Kelstrup, 2016; Rich, 2005; Stone, 1996). Hence, in order to understand how they influence policy making, it is important to answer the following questions: how think tanks delineate one problem as relevant for policy makers, how they develop policy proposals for dealing with such issue, and eventually, which strategies they are applying for making their proposals appealing (Kingdon, 2014). From the viewpoint of policy making, think tanks can influence different stages of this process - in different ways and to different degree (Rich, et al., 2011), but their influence is not always easy to evaluate as the process of transformation of one idea into policy can take decades, with the interaction of numerous agents and modifications of original idea (Weidenbaum, 2010). According to Kingdon's Multiple Streams approach (1984; 2014), these agents bringing different ideas into policy market and trying to put them on policy makers’ agenda can be considered policy entrepreneurs “willing to invest their resources in return for future policies they favor” (2014, p. 20). This paper assumes think tanks with their unique approach as one of them.

However, COVID-19 pandemic as an unprecedented crisis turning upside down institutions and societies (Bieber, et al., 2020) had an impact even on these policy entrepreneurs as it changed the way the issues are set on the agenda. COVID-19 prompted policy makers to act fast, to create easily implementable policy solutions to the challenges imposed to the citizens and economies. Crisis did not force just decision makers to react promptly, but as well think tanks around the world, to come up with constructive and applicable policy contributions, in order to stay relevant and “demonstrate the critical role they play in improving decision-making at a dynamic time” (Gutbrod and Bruckner, 2020, para. 1).

Think tanks’ role in policy creation during COVID-19 crisis perhaps is even more important in the contexts with distorted policy processes, such as the case of Serbia, in which “policy making is taking place behind the curtains, public hearings and other means to include stakeholders are rare and often formal…while decision makers see local civil society (and think tanks) as a nuisance that hinder government plans to shape these countries to their liking” (Galushko & Djordjevic, 2018, p. 207). In such circumstances, think tanks could help to improve the quality of policy making, providing data to assess the importance of the problem and offering diverse policy proposals on how to resolve it (Buldioski, 2009).

On the other hand, a crisis, such as COVID-19, according to Kingdon (2014) can be a trigger for a window of opportunity to open, creating favorable conditions for policy entrepreneurs and their policy proposals to be placed on decision makers’ agenda. Thus, here will be examined to what extent proposals advocated by selected Serbian think tanks matched those introduced by the Government. However, it is important to emphasize that the aim is not to measure influence of selected think tanks, as documental analysis is not sufficient for such purpose, but should be the subject of further analysis (Yin, 2003).

Summing-up, this paper analyzes the role of Serbian think tanks as policy entrepreneurs during COVID-19 crisis, taking Kingdon’s Multiple Streams approach (1984) as a framework for such analysis. Upon introduction, the following section focuses on elements of the Multiple Streams model important for understanding how policy entrepreneurs influence policy making processes. The third section describes COVID-19 policy response by the Serbian government, in order to assess the extent to which think tanks’ proposals match with those adopted by the Government. The fourth highlights the specificities of Serbian think tanks market, while the fifth brings together Kingdon’s framework and the findings from document analysis of selected think tanks’ policy products. The paper ends with the conclusions of the document analysis, which can serve as the recommendations for other think tanks on how to turn the threat, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, into a window of opportunity for their pet proposals to be to be taken into consideration by policy makers.

Kingdon’s Multiple Streams Model

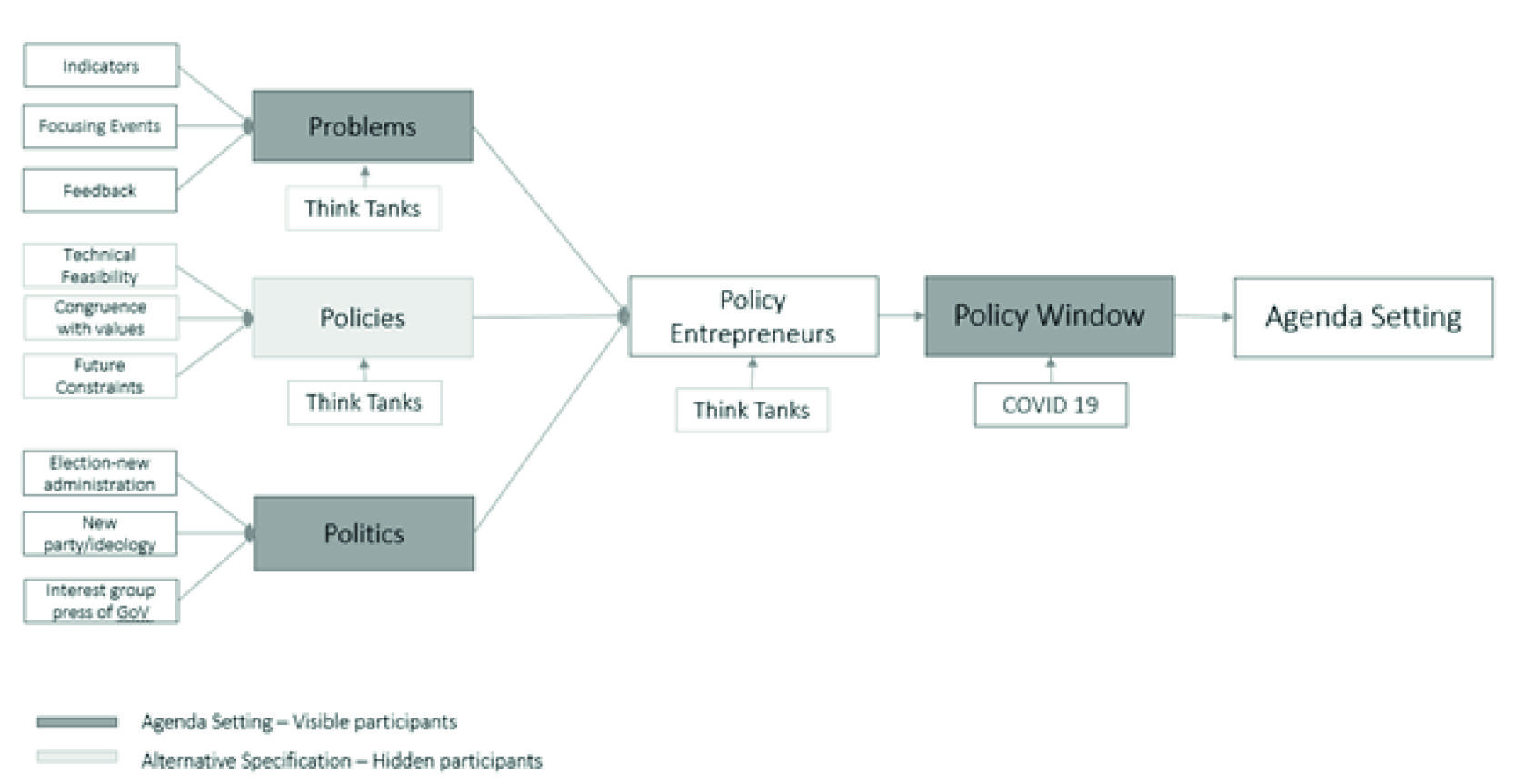

Since 1984 when John Kingdon published his seminal book Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies, the Multiple Streams became one of the most-cited theoretical approaches in this field of policy analysis (see Brunner, 2008; Farley, et al., 2007; Wu, 2018; Zahariadis 1992, 1995). It is a classical agenda setting approach, commonly used for explaining how some issues find their place on the governmental agenda (Kingdon, 2014). Kingdon focuses on the initial stage of policy making, and makes differentiation between two processes of particular interest (p. 196). The first one is agenda setting, the process of narrowing from the all possible subjects to those that are worthy for governmental officials to focus on (p. 196). Additionally, unlike other authors who rather use the term ‘agenda setting’ for both processes, Kingdon introduces the concept of ‘alternative specification‘, and explains that once the problem is placed on the agenda, different policy alternatives are discussed, and some are taken more seriously (p. 4).

In order to answer the questions how “agendas are set and alternatives are specified”, he highlights three processes: problems, policies, and politics (Kingdon, 2014, p. 16). Different policy actors (including think tanks) are recognizing problems, and afterwards are developing policy proposals to tackle such issues and engage in political activities in order to set them on governmental agenda (p. 196).

Regarding problem stream, Kingdon argues that different mechanisms are used by participants to transform regular conditions into important problems, including indicators that show that condition changes; focusing events such as crisis, personal experience or symbols; and formal or informal feedback from existing programs (p. 197-198). Events in politics such as elections and new administration or changes in national mood have high influence on agenda setting, and contrary to other streams, consensus here is built by bargaining, instead of persuasion (p. 198-199). Problem and politics streams Kingdon is using to explain how the issues are set on agenda, together with the concept of visible participants “those who receive considerable press and public attention”, such as president, high government officials, MPs, or political party representatives (p. 199). If they are enhancing the issue, there is high possibility that it will be placed on the agenda (p. 199).

Alternatively, in the policy stream, within the process of alternative specification, hidden cluster participants made of researchers, consultants, academics and bureaucrats are creating plentiful policy solutions for different problems, and pushing for them via public hearings, speeches, media statements, policy products, etc. (p. 200). These policy ideas are floating and blending in “policy primeval soup”, making the origin of ideas obscure, but not the selection - it is based on their “technical feasibility, congruence with the values of community members, and the anticipation of future constraints” (p. 200).

Regular or sudden events in either political or problem stream can trigger a window of opportunity to open, followed by coupling of all three streams that creates favorable conditions for the problem to be placed on the agenda or policy alternative to be taken into consideration (p. 201). These policy windows are rare and of short duration, thus “advocates of pet proposals” need to act promptly, keeping their alternatives ready for such opportunity (p. 203-204). Boosting this conjuncture can be brought by policy entrepreneurs, who are ready to invest their resources as an exchange for the policy they are keen on (p. 204).

Following the approach developed by Kingdon on the US case, empirical studies for Multiple Streams model were conducted for United Kingdom (Münter 2005; Zahariadis, 1995), France (Zahariadis, 1995), Germany (Brunner, 2008; Nill, 2002; Zahariadis, 1995), Canada (Howlett, 1998), Denmark (Bundgaard & Vrangbæk, 2007), and European Union (Copeland & James 2014). This paper focuses on Serbian context and the think tanks in the role of policy entrepreneurs, additionally assessing to what extent ideas brought by them correspond with the ones the Government adopted as response to the COVID-19 crisis. In the Figure 1 key elements of Multiple Streams approach along with the hypothesized role of think tanks acting as policy entrepreneurs during COVID-19 is presented.

COVID-19 Policy response

How does one problem become important for Governments to deal with? Perhaps this question raised by Kingdon (2014) is less relevant when it comes to worldwide pandemic such as COVID-19, “an unprecedented challenge with very severe socio-economic consequence” (European Council, 2020, para. 1). Yet COVID-19 imposed numerous problems that forced decision makers to deal with and respond with urgent policies (OECD, 2020). Soon after health issues, economic problems emerged, competing for their priority on the governments’ agendas (United Nations, 2020). In order to mitigate the negative impact of COVID-19 on their economies and secure a sustainable recovery, governments all around the world adopted support packages, consisting of different measures such as “tax and spending, loans and guarantees, monetary instruments, and foreign exchange operations” (IMF, 2020, para. 2).

So did the Government of Serbia: on April 1st 2020 Minister of Finance introduced the EUR 5.1 billion package of measures, equivalent to half of the State budget and 11% of national GDP, with the aim of stimulating the economy and reducing negative consequences (OECD, 2020). The Adopted Program of Economic Measures is made of four sets of policies, including tax policy measures, direct financial aid to the private sector, liquidity measures and other measures (direct cash grant and moratorium on dividend payments) (The Government of the Republic of Serbia, 2020, p. 10). Meanwhile, during the process of Program creation - as even mentioned in the Program (p. 6) - various policy entrepreneurs were interacting with the Government representatives, addressing important issues (agenda setting) and proposing policy solutions (alternative specification) to be considered when defining a support package. These proposals obtained from the chambers of commerce, university professors, business associations, etc., mostly concerned about the preservation of jobs and the maintenance of liquidity, eventually were taken into consideration, but not all of them were accepted (p. 6). This paper is particularly interested in the role of think tank organizations in creation of COVID-19 package of measures, by analyzing problems they addressed, solutions they offered, strategies they applied, and eventually by assessing to what extent their proposals match with the official Government measures. Before the analysis, a short overview of the think tank market in Serbia is presented.

Serbian think tanks market

The opinions about think tanks’ role in Serbia remain conflicting since the 1990s when they started developing: while optimists considered it as termination of state control over data and research, introduction of evidence-based policy making and credible source for political debate, sceptics claimed that “intellectual elite [is] creating new heavens for their own well-being”, that think tanks were donors’ project to manipulate new democracies and attempt to make state research capacities even weaker (Buldioski, 2007, p. 51). In addition to the think tanks, similar hybrid organizations that “combine policy research with other functions, such as monitoring and watchdog activities, consulting, service delivery, or grassroots advocacy” (Galushko & Djordjevic, 2018, p. 208) have as well active role in providing policy advice and research in Serbia, and depending on the authors, these hybrid organizations can be considered think tanksi (see Bogdanovic, 2016).

It is a relatively small market: according to McGann (2020)ii 14 think tanks are active in Serbia, mainly covering the topics of European integration, international relations and social policy, but they deal with cross-sectoral topics too (Bogdanovic, 2016, p. 3). These are rather small organizations with 1 to 3 researchers that due to unstable funding outsource policy consultants and researchers for the needs of specific projects (Bogdanovic, 2016, p. 3). They are often lacking strategic orientation, their credibility is highly dependent on their leaders and are not always transparent in their operations, which contributes to the distrust among decision makers - more on personal base than empirical evidence (Galushko & Djordjevic, 2018). However, in these three decades of think tanks’ presence in Serbia, they were initiators, i.e. policy entrepreneurs for some of the far-reaching policy reforms, including participation of civil society sector in EU accession process and mainstreaming gender equality into security, despite all the obstacles they were facing in such attempts (Bogdanovic, 2016, p. 4).

Results

Hence, the aim of this paper is to examine whether Serbian think tanks acted as policy entrepreneurs during COVID-19 crisis, and to what extent their policy proposals corresponded with the ones the Government adopted. In order to answer these research questions case study design is applied, examining in detail the activities of four (hybrid) think tanksiii - European Policy Centre (CEP), National Coalition for Decentralization (NCD), European Movement in Serbia (EMINS) and National Alliance for Local Economic Development (NALED). Even though Galushko and Djordjevic (2018) define NALED and EMINS as hybrid organizations that in addition to policy research perform other, complementary functions, in this analysis following Bogdanovic (2016), a common term think tank will be used for all four organizations.

The following discussion brings together Kingdon’s framework and the findings obtained from document analysis, i.e. analysis of policy products of selected cases published on their web sites (54 in total), in the two months period from March 15th to May 15th 2020 (see Appendix A), along with the Government Program of Economic Measures adopted in that period to reduce the negative effects of COVID-19. Bearing in mind that “document analysis is often used in combination with other qualitative research methods as a means of triangulation” (Bowen, 2009, p. 28), inference obtained from document analysis here should be treated as the subject of further investigation, and not definite finding (Yin, 2003).

Problem Stream

According to Multiple Stream approach, one of the moments where policy entrepreneurs can be found in the pre-decision process of policy making is in problem stream, by “pushing their concerns about certain problems higher on the agenda” (Kingdon, 2014, p. 204). The findings of the document analysis shows that the activities of Serbian think tanks are in line with Kingdon’s conclusion: since the moment the emergency state was declared on March 15th 2020, they started addressing many important issues to be placed on policy makers’ agenda - 19 in total (see Table 1).

Table 1 List of COVID-19 issues addressed by the selected Serbian think tanks, in the period March 15th - May 15th 2020.

| No | Issues | Think tanks |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Government economic measures to mitigate the negative impact of COVID-19 | CEP, EMINS, NALED, NCD |

| 2 | Accountability and Transparency of Parliament and Government during COVID-19 crisis | EMINS, NCD, CEP |

| 3 | Influence of COVID-19 on modernization of public administration | CEP |

| 4 | Influence of COVID-19 on local governments | NALED |

| 5 | Influence of COVID-19 on labor market | EMINS |

| 6 | Influence of COVID-19 on the youth on labor market | EMINS |

| 7 | Functioning of the health system during COVID-19 crisis | NALED |

| 8 | Influence of COVID-19 on agriculture and beekeeping | NALED |

| 9 | Influence of COVID-19 on construction, infrastructure and transport sectors | NALED |

| 10 | COVID-19 and VAT on food and hygiene products donations | NALED |

| 11 | Illegal actions of economic entities during COVID-19 crisis | NALED |

| 12 | Influence of COVID-19 on travelling | EMINS |

| 13 | Influence of COVID-19 on foreign trade | EMINS |

| 14 | Necessity of regional cooperation to overcome crisis | CEP, EMINS |

| 15 | COVID-19 and EU enlargement (Zagreb Summit) | CEP, EMINS |

| 16 | Increasing China influence and undermining the credibility of the EU during COVID-19 crisis | CEP |

| 17 | Centralization of information and fake news during COVID-19 crisis | CEP, NCD |

| 18 | Citizens’ education about the COVID-19 protective measures | NCD |

| 19 | Role of civil society and think tanks during COVID-19 crisis | CEP, EMINS |

As one of the criteria for case selection was the presence of the content related to the government economic measures, consequently the problem of negative impact of COVID-19 on the economy was the one discussed by all selected organizations. However, they covered different perspectives: while EMINS focused more on the labor market in general, and the impact on youth in particular, NALED stressed the concerns of the most affected sectors, such as construction, transport and agriculture. CEP and EMINS discussed the importance of regional cooperation and EU paths for Serbia to overcome the crisis, with particularly beneficial roles of civil society and think tanks in such processes (EMINS, CEP). Problems of centralization of information and fake news were under the spotlight of NCD and CEP, while calling for greater accountability and transparency of Parliament and Government (EMINS, CEP, NCD).

Nevertheless, even though these problems might be relevant, not all of them were new, and had already their place on think tanks’ agenda before the crisis appearediv. For instance, the decision of European Policy Centre and European Movement in Serbia (while not NALED and NCD) to discuss the issue of Serbia's European path as a way out of the crisis is in accordance with their organizational orientation towards the EU. Similarly, as membership organization consisted of businesses and local governments, NALED particularly addressed the problems these agents were facing during crisis (reduction of local government revenues, and tax and non-tax burden for businesses); while National Coalition for Decentralization stressed the problem of increasing centralization of governance during crisis, which is in line with what they advocate regardless of COVID-19 crisis.

Policy Stream

In addition to addressing issues to be placed on the governmental agenda, policy entrepreneurs have also an important role in the process of alternative specification and policy stream, by creating and pushing for different policy alternatives (Kingdon, 2014). Similar to this is their role of making couplings, which means they utilize auspicious momentum to link their pet proposals to the pressing problems demanding attention (p. 204). These roles of policy entrepreneurs are as well evident in the case of Serbian think tanks.

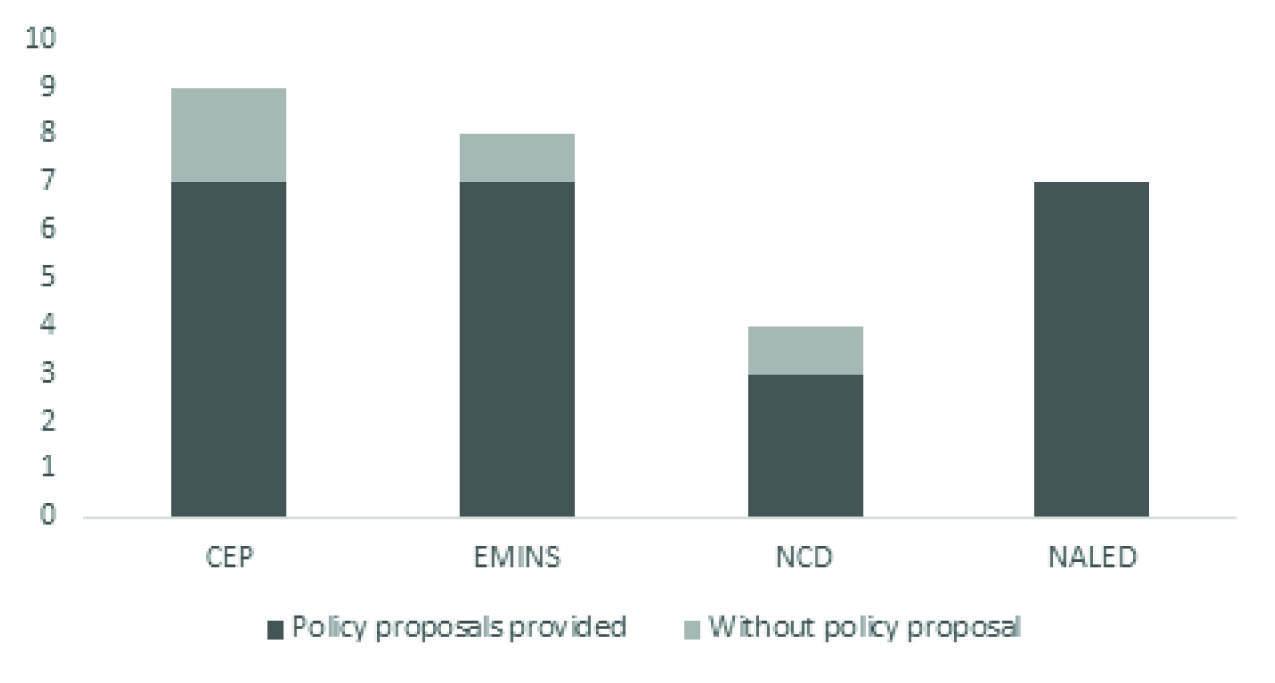

The findings show that even though they did not provide policy alternatives for all the problems they addressed, for the vast majority they did: overall, in 24 out of 28 of cases when they raised an issue it was accompanied with the specific recommendation how to deal with it (see Figure 2). Such result is in accordance with the role of a hidden cluster of experts within the policy stream, creating and recreating policy alternatives (Kingdon, 2014, p. 70). However, the complexity and robustness of these proposals vary significantly, from very general and vague to quite much specific and practical solutions. Moreover, here is also evident the difference between selected cases: while NCD provided fewer proposals in general, and more elaborate ones in particular (this also applies to EMINS), CEP and NALED (especially), were way more pragmatic, offering hands-on solutions to the Government and trying to impose themselves as a relevant partners.

In the same way they advocated for problems that are in accordance with their area of work, they used the crisis to push for their pet proposals: those think tanks are very keen on, and have already advocated for before the crisis. Each of them took the opportunity to once again promote their preferred solutions: NALED advocated for extension of tax exemption measure for business beginners and implementation of e-Agrar system; NCD called for cooperation between national and local governments to ensure transparency of information; CEP stressed the importance of opening up government data to citizens; while EMINS invited CSOs from the region to make joint forces in order to foster their governments to act coordinated.

Pushing forward

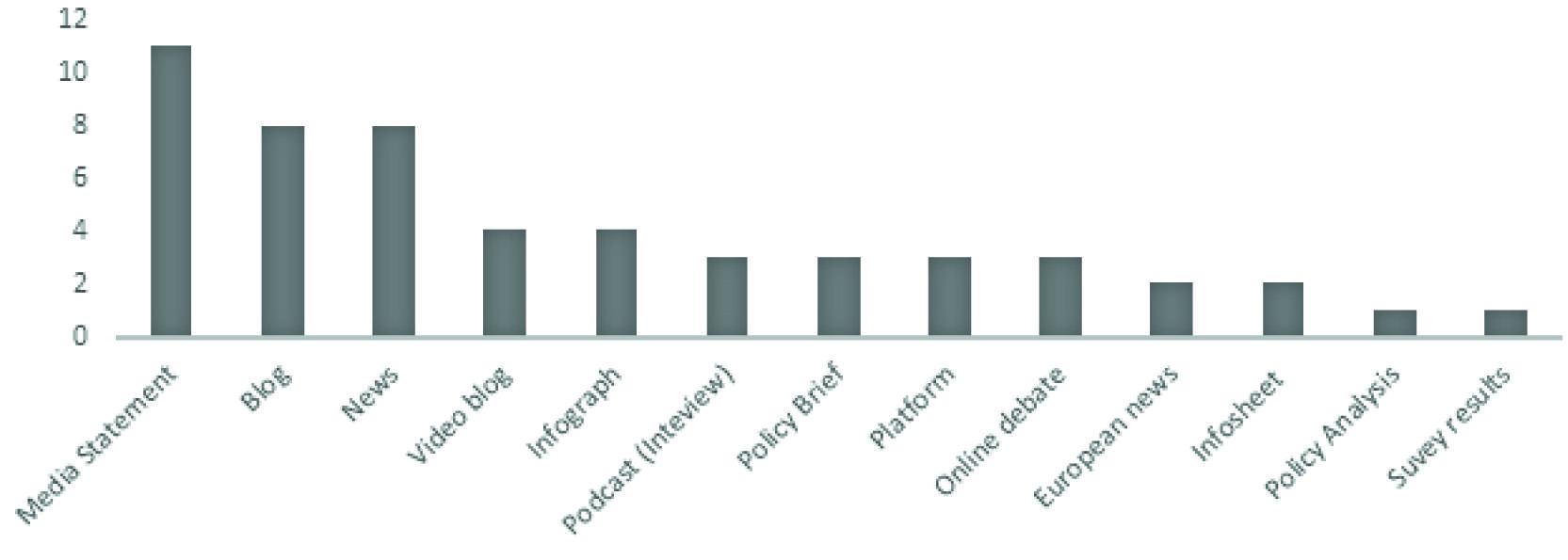

In addition to addressing problems and offering solutions, Kingdon (2014) describes entrepreneurs as those “pushing”, which implies specific, accompanying activities of promotion and advocacy. Bearing in mind that the COVID-19 emergency state introduced the banning of gatherings indoors more than five people (Official Gazette of RS, No. 39), and that civil servants have largely switched to working from home, with limited meeting capacity, in this paper, think tanks’ web strategies for pushing their proposals were analyzed.

As policy windows are rare and of short duration, policy entrepreneurs need to act promptly, having their pet proposals ready to jump in once the window of opportunity opens (Kingdon, 2014). However, among selected think tanks, there was considerable difference regarding the speed of their reaction: while NALED published 10 proposals for the Government to mitigate the crisis a day after emergency state was declared, EMINS published its first COVID-19 content almost a month later (see Appendix A).

Regarding the strategies they implemented for “pushing”, the most used tool was media statement as a take-away product for media, which facilitates the placement of think tanks’ message. NCD and NALED conveyed the online surveys providing original data for their advocacy (in the forms of info-graphs and policy briefs), while self-recorded video content in the form of video blogs (EMINS) and online debates (NCD) were innovative ways to reach the public, without violating the rule of social distancing. Additional strategies applied for strengthening arguments, were putting the same content in different form (for instance, analysis and info-graph, see Appendix A) and acting in coalitions: together with three other organizationsv NALED pushed for exemptions from VAT on donations; EMINS called for better regional coordination along with 38 organizations; while there was even collaborative activity between selected cases: CEP and NALED organized a joint webinar to discuss adopted economic measures.

With the exception of NALED, think tanks were utilizing experts and their recognizable names to attract attention, in different forms. Half of all content, CEP put in the form of a blog, as an expert opinion, including interpretation of the problem along with recommendations. Similar strategy, but in video format (vlog) EMINS applied, while NCD opted for online debates of internal and external experts. On the other hand, NALED provided much more analytical products compared to others, based on their original data, and developed sets of practical recommendations for decision makers for different business sectors, Q&A platform for citizens and donation platform for helping local communities and healthcare institutions.

COVID-19: Window of opportunity?

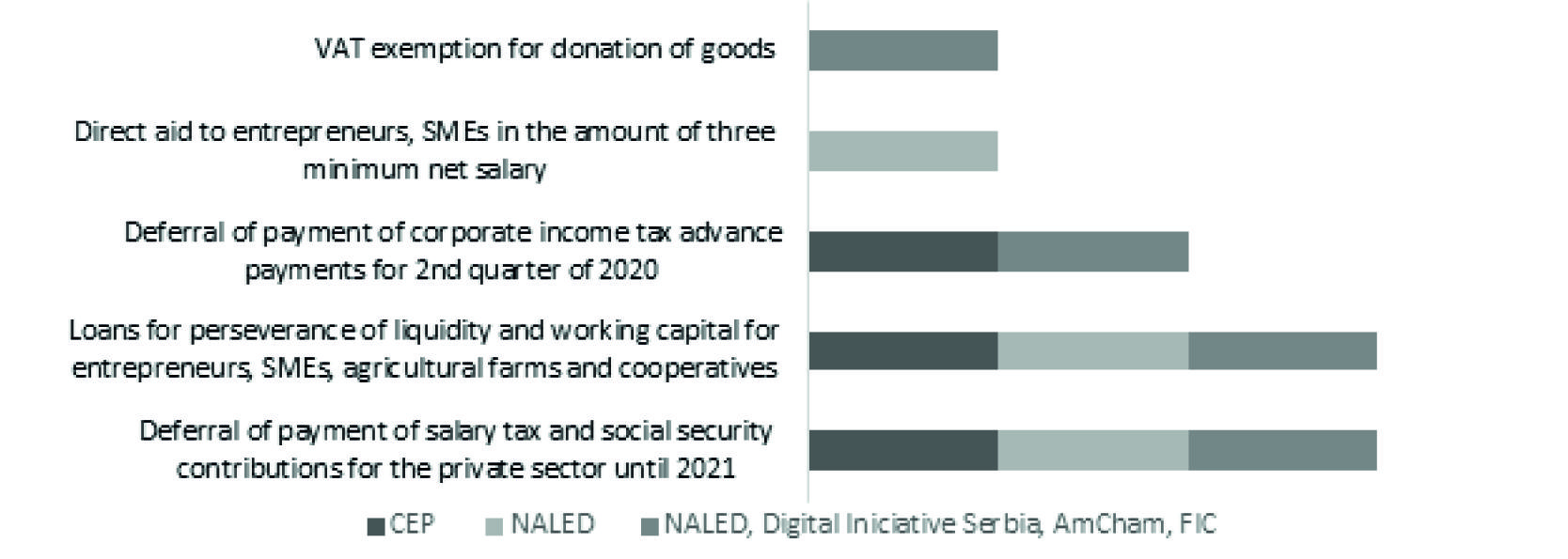

The last question of this analysis is whether COVID-19 was indeed the policy window for think tanks, i.e. to what extent proposals advocated by policy entrepreneurs matched with those introduced by the Government? In this subsection focus is on the specific policy products made by CEP and NALED vi- 10 measures for the Government to introduce to mitigate the negative effects of the crisis. NALED provided even two versions of these proposals: the second edition was modified compared to the first, it was prepared in alliance with other business associations and both were taken as the subject of analysisvii. Even though NALED was officially recognized as one of the relevant contributors in Governmental Program (2020, p. 6), it is important to emphasize that this paper does not aim to measure policy influence of think tanks, as documental analysis is not sufficient for such purpose, but should be the subject of further analysis (Yin, 2003). Instead, it examines the role of think tanks as policy entrepreneurs, and whether and how they benefited from COVID-19 crisis to set their policy proposals on policy makers’ agenda.

The findings show that five out of nine measures introduced by the Government were recognized as important by CEP and NALED as well (as seen in Figure 4). While some of their proposals were fully matching, in others cases they had slightly different views on how to resolve these issues (e.g. direct aid for businesses). Reorganization of salary tax and social contributions payments, and provision of loans for businesses’ liquidity were proposals advocated by all organizations, while advance payment of corporate income tax was addressed in two (out of three) documents, with different proposals how to deal with it (deferral vs abolishment). NALED also advocated for one-time financial support for businesses, and in coalition with other organizations called for abolishing VAT on donations: both measures corresponding with the Government policy.

Notes: Measures that the Government of Serbia introduced, and were not advocated by selected think tanks are following: Direct aid to large companies in the amount of 50% of three minimum net salary; Financial support through guarantee scheme to commercial banks; Moratorium on dividend payments; Direct aid to 18+ Serbian citizens through one-off payment.

Figure 4 Matching of Government package of economic measures and policy proposals provided by NALED and CEP.

However, these proposed measures were neither CEP nor NALED pet proposals, but rather responses tailored specifically for this situationviii. For instance, in its annual publication - Grey book (2020, p. 23), NALED advocated for permanent -and not temporary- reduction of the tax burden on wages, while the taxation issues were never on the CEP agenda before the crisis. It means that think tanks were quite flexible to shape their pet proposals in accordance with the new conditions, but also brave enough to deal with the completely new topics in order to stay relevant actors on the policy stage.

Conclusions

Summing up the findings, it may be concluded that Serbian think tanks played the role of policy entrepreneurs during COVID-19 crisis, acting promptly to seize the window of opportunity and placing the issues with the accompanying pet proposals on policy makers’ agenda. Based on the insights obtained from the examined cases in this analysis, the following conclusions, which could serve as recommendations (or know-how) for other policy entrepreneurs, can be made.

First of all, even in the crisis period, think tanks did not recede from their defined strategic orientations: as soon as the emergency state was declared, they started addressing the issues they considered important, that were in line with their positions, and were already familiar with. They framed them in the new context of COVID-19 and pushed forward by applying innovative mechanisms for advocacy. However, they did not hesitate to introduce even the new topics on their agenda so as to stay relevant in the changed circumstances.

Additionally, bearing in mind that the creation of policy relevant research is think tanks’ uniqueness compared to other policy entrepreneurs, during COVID-19 crisis they acted as the partners offering their know-how to policy makers, i.e. providing specific proposals on how to resolve the relevant problems they addressed. Similarly to their strategy to address the problems already on their agenda, they also tried to utilize the crisis to advocate for their pet proposals. In order to remain important players, some of them developed quite specific, hands-on policy solutions for the Government, eventually conquering their place on the Government’s agenda.

COVID-19 demonstrated as well how creative think tanks as policy entrepreneurs can be. In addition to their standard policy products (policy brief, media statement, blog post), in the changed reality they soon found new and innovative ways to disseminate messages to their target audiences, without violating the rule of social distancing, via vlogs, podcasts and online debates. In order to strengthen their arguments they acted in coalitions with other policy entrepreneurs, on both national and regional level, and utilized big names in the field to advocate for their pet proposals.

Finally, even though their approaches for advocacy and promotion differed (considerably in some situations), the proposals Serbian think tanks advocated for matched significantly with those adopted by the Government. However, in order to assess their policy influence, i.e. understand better whether they were the ones bringing such ideas to policy makers, further overarching analysis is needed.