1.Introduction

Health inequalities are escalating globally, and both high- and low-income countries are struggling to ensure accessible, equitable, and high-quality services for their populations (Godoy-Ruiz et al., 2016). In such context, research initiatives conducted within a local context alone are insufficient to produce empirical pieces of evidence to guide the responses to the needs and issues faced by the global community (Godoy-Ruiz et al., 2016). Current conditions and evolutions to scientific advancements occurring through collaboration and trans-cultural initiatives should be addressed through the internationalization of research (Antelo, 2012). Globalization, which has significant impacts on international markets and the global economy, has created conditions for the integration of knowledge and ideas across national borders (Antelo, 2012). Advancements in technology, as well as inventions and the heightened use of sophisticated devices, have created an opportunity for the facilitation of communication and knowledge exchange in research at all levels of social and economic development worldwide (Antelo, 2012).Woldegiyorgis et al. (2018) have emphasized that internationalization has often and most recently been associated with the movement of students for academic purposes or with its influence on education. In the literature, this term is very seldom linked with or explored concerning the internationalization of research. Research is inherently considered international and boundary-less, a notion that dates back to the early days of medieval universities, when the research was conducted by ‘wandering’ scholars (Woldegiyorgis et al., 2018). The internationalization of research relates to individual research as having a primary scope or orientation on international and global health type issues (Rostan & Ceravolo, 2015). For that, also at stake, are the collaboration and the partnerships with international colleagues during the research process, the utilization of a language (for English-speaking countries) other than English as the primary language of exploration and dissemination, and the provision of funding from international organizations (Rostan & Ceravolo, 2015). Higher academic institutions are well known as knowledge producers and major sources of research activities and innovations (Antelo, 2012). They provide an ideal environment for faculty and students to collaborate within schools and across departments and faculties and are not constrained by national borders (Woldegiyorgis et al., 2018). While a small, select number of individual researchers in these institutions collaborate globally, seldom do these institutions include strategies for the internationalization of research in their academic mission statements. This may be due in part to the fact that very minimal research has been conducted on factors that support and/or hinder the internationalization of research. A quantitative study of 11 European countries exploring the impact of international research partnerships on individual research productivity found that such partnerships create opportunities for substantially higher research productions (Kwiek, 2015). These opportunities include higher publication rates, access to a multitude of resources, and prestige in relation to accumulative advantages (Kwiek, 2015). While cross-national and cross-cultural differences may apply, these are mitigated by hiring and retaining diverse faculty and researchers within academic and other knowledge-producing and -advancing institutions (Kwiek, 2015). Engaging in research with collaborators that are geographically dispersed brings the benefits of application and the use of diverse methodologies, theoretical frameworks and models, research designs, and ideas/thought processes (Tight, 2019). The lack of funding for such international and global health-related research initiatives is one major barrier to the internationalization of research; a barrier that delays increased cross-national and cross-cultural collaborations for the purpose of knowledge creation, exchange, and translation. Research is not being conducted in an equitable way, as it does not address health needs in a balanced way (Yegros-Yegros et al., 2020). Research on diseases and issues impacting the health of individuals in high-income countries, primarily for the benefit of Caucasians, receives far more attention, funding, and support when compared to research on the health of individuals in low-income countries (Yegros-Yegros et al., 2020). Even when comparing a health-related issue or a condition of a relative level of burden in both higher-income and lower-income countries, higher- and middle-income countries still account for most of the research that gets funded and disseminated (Yegros-Yegros et al., 2020). Particular attention needs to be paid to trust development and the mitigation of inherent power imbalances that can impact the collaboration efforts that extend beyond country borders (Kerasidou, 2018), especially when collaborating countries do not align on economic and political spheres. The internationalization of research is a solution to conduct equitable research, as it allows for the democratization of knowledge, the deliberate creating, exchanging, and translating of knowledge that asserts democratic constraints on the global exercise of power (Miller, 2007). The internationalization of research allows for knowledge to be disseminated and utilized by global citizens, not just remain with a select group of elite individuals. In the context of the global need for the production of knowledge with socially vulnerable populations, and the concomitant, minimal availability of funding for international research, university researchers should innovate. The mobilization of researchers’ social and professional networks, and the constant reformulation of intellectual partnerships in research, are today the most common strategies to face challenges to the implementation of research in international settings. Many societies are becoming research literate. Governments increasingly take research capacity-building and its mastery as part of their country’s social development and the enhancement of individuals’ quality of life, while dealing with the high degree of complexity in the relationship between science, technology, and society (The Center for Research on Science, Technology and Society Team, 2021). Citizens gradually acknowledge the value of science and research education and welcome the benefits of scientific deeds for their health and social wellness (Nature, 2017). The success of this double process of research literacy relies on the social leadership of scientists who act as real social champions to motivate, role-model, and mobilize citizens’ potential towards their engagement to contribute to research.The goal of this chapter is to discuss critical methodological issues in the process of designing and implementing international online survey research. This discussion refers to quantitative research instrumentation that was inspired by researchers’ knowledge and expertise in the area of qualitative research. This is done in the context of responding to the need for innovation in data collection instrumentation to expand their responsiveness to the international field and the participants’ characteristics.

2.Online International Research

The state of art about the contact and interactions among individuals recommends that it can be understood as fundamental for society to buy in to research as a necessary asset for the collective progress and benefits facilitated by robust digital health research (The Lancet Digital Health, 2020). The use of technology for research has increased since the 1990s (Thunberg & Arnell, 2021) and includes digital methods such as (web) online surveys, which opened new interactive doors due to the indirect contact among individuals and allowed passionate researchers to present research to prospective participants to get them involved. Online research sets boundaries for “ideal participants”: (a) those who are computer literate; (b) have access to electronic devices; (c) are able to read and type without any supervision or help; (d) are able to read, interpret, and understand the information displayed in a data collection tool provided on a screen. The advantages of computer-assisted data collection have been acknowledged for many years. Advantages include the possibility of skipping repetitive answers, preventing forgotten asked questions by an interviewer, and more honesty by participants. Honesty is considered as there is no direct contact with an interviewer, particularly when undesirable or inappropriate behaviours are being explored (Streiner & Norman, 1996). Undeniably, the social inclusion of the individuals most needed to participate in online research is jeopardized. Frequently, researchers who do not have access to large funding to conduct international research may be frustrated in their desire to include some hard-to-reach populations. Core questions for the researchers’ concern balancing their desire for stimulating and amplifying the discourse of some voiceless populations, their passion for discovery, the awareness of a lack of funds, and a genuine conscientiousness of an emerging community of researchers advocating for a more global citizenship mind-frame. How to design methodological, rigorous plans of research with the creation and development of original data collection tools and strategies sensitive to all aforementioned issues has been a constant struggle for many researchers. Another emerging concern is the researcher’s ability to analyse large volumes of quantitative or qualitative evidence. It is especially important when being pressured by time, repetitive steps of coding, application of a hybrid inductive/deductive approach, as well as the work conducted by a large team of researchers/experts (Skillman et al., 2019).At stake are relevant differences and particularities related to prospective research settings, the availability of operational resources, and the research culture, including the local society’s familiarity with research. The idea of conducting international, online, remote data collection activities should be informed by many pieces of extra-methodological information, the multifaceted human dimension among them. It is safe to say that one of the undeniable strengths embedded in the practice of qualitative research is the (almost) sine qua non opportunity to establish direct researcher-participant contact. Such space for dialogue can be surely created in other data collection contexts where the indirect contact between the researcher-participant is a unsurmontable technical barrier. Despite its recognized benefits, online data collection can be either an excitement or an unconscious risk for unpredictable situations. Such unpredictability can be explained by the options of the mode of communication and temporality (synchronous or asynchronous) for data collection (Namey et al., 2020). A new trend in qualitative research is the use of qualitative surveys that allow researchers to “capture what is important to participants and access their language and terminology” (Braun et al., 2020, p. 1). This type of survey is defined as a set of open-ended questions proposed by researchers to explore a given topic, and is suitable as a qualitative research tool, despite some existing misconceptions (Braun et al., 2020). However, this type of survey can also use a mix of multiple-choice, closed-ended questions, as well as open ones, to collect information about participants’ experiences, practices, discourse, etc. The exclusive use of open-ended questions ideally require the availability of e-equipment, such as a desktop or laptop computer, or even a tablet that could ease the typing tasks. When only a small e-device, such as a cell phone, is available, participants are less likely to be able to type long texts, thus limiting a full sharing of accounts. Challenges include the promotion of social inclusiveness of those prospective participants living in remote or deprived areas, having a cell phone with internet for connection, and living with cognitive- and motor-particular needs. Researchers should demonstrate an ability to design data collection tools and define feasible research fieldwork procedures to implement their research with international and diverse populations. Therefore, this chapter fills in knowledge gaps by introducing the context of experiences relating to several quantitative online surveys conducted initially during an Ebola epidemic in Francophone African countries, and the discovery of unknown factors that emerged throughout the process. Other multisite, international, and nationwide similar research followed. Most recently, due to the unpredictable context for online data collection during the COVID-19 pandemic, research in Canada, Brazil, and Francophone African countries uncovered factors related to engagement, commitment, and collaboration. The array of learned methodological lessons in the endeavour to conduct online surveys within the scope of global health is presented. By pointing out opportunities, achievements, certainty, guarantees, and surprises in the implemented research, the authors also disclose their deeds and how they met challenges and disappointments. Courses of action and adopted solutions are presented to fill in knowledge gaps in these areas.

3.First Insights for an Alternative and Innovative Design

The first insights for the conception of a questionnaire to be implemented in an international initiative were not for an online survey. They were a response to an opportunity to conduct a service evaluation with Brazilian Community Health Agents (CHAs) in their work to address and act on situations of social vulnerability lived by the population they served. This work was done within the context of their practice in the community settings integrating actions with the multi-professional team of the local Family Health Strategy (FHS). The evaluation team was located in Toronto, Canada, and only those who were Brazilian- -born professionals were knowledgeable about the CHAs’ scope of practice. The work was initiated in 2007 with less multifunctional communication technology, and the initial challenge was to approximate the Brazilian social reality for the Canadian evaluators, as well as the context of health promotion as implemented by CHAs. Brazilian members located in Brazil decided to record two short videos, one about the multi-professional actions of the FHS team, and another showcasing CHAs in action. The Toronto team watched the videos together, and then debriefed and brain-stormed about aspects to be explored in a questionnaire due to the impossibility of directly collecting accounts and experiences of almost 210 CHAs in the local municipality. The two Brazilian faculty in this team coordinated the process of formulating questions by concomitantly reviewing together the educational curriculum for CHAs’ training with detailed areas of practice. Furthermore, they consulted Brazilian policies and legislation that framed the CHAs’ possible actions of denunciation to police and official social services, and the referral of vulnerable minors, young women, and seniors to medical and social services. This working method allowed them to create an overall picture where effective interventions in case of social vulnerabilities could be legally implemented. With such a reality pictured, the formulation of questions in a multiple choice was done, recognizing that all options could in fact represent actual, feasible courses of action in any given situation of social vulnerability encountered by the CHAs. Moreover, each possible action was proposed considering critical issues related to the risky work conditions faced by CHAs due to the rampant community violence and public insecurity in Brazil. It is noteworthy to say that CHAs’ areas of work were shantytowns, places of the intense presence of drug dealers, children in lack of surveillance, seniors’ abandonment, interpersonal violence, etc. Furthermore, their personal safety would be jeopardized, as any direct denunciation resulting in a victim’s legal removal automatically implied that the denunciation was done by a CHA, exposing her/him to a reprisal by the agent of violence. The resulting questionnaire had 28 close-ended questions, each of them addressing a different aspect of social vulnerability, such as domestic violence, seniors’ food deprivation, suspicion of sexual abuse, identification of psychological harassment, disrespect of disabled individuals’ human rights, etc. It was pilot-tested in Brazil with five CHAs, and then refined and copy printed, as well as applied to 189 CHAs in a collective session. It is necessary to say that the form had only closed questions, and while responding, the CHAs asked for permission to write a justification of each chosen answer. As it was the first time that they took part in an evaluative initiative, permission was granted. As a result, the evaluation team obtained approximately 5,292 short sentences as accounts about the CHAs’ actions and/or interventions in all presented situations. This evidence was treated using a qualitative approach. The success of this international project was expressed by the use of the first report in plain language by CHAs for political advocacy action, and guided the City Hall’s councillors to vote for an increase in the municipality health budget. For more information, see Zanchetta et al. (2009).This experience imparted very important lessons that highly influenced the international online surveys implemented afterwards. Relevant lessons ignited the curiosity to further trials in other contexts and populations, and most importantly within the perspective of the international scope of online research. The key learning is in regards to how: a) A skilled and experienced qualitative researcher can guide a team to reshape the understanding of aesthetic and artistic knowledge in the process of use of inductive thoughts; b)Imagination, creativity, and audacity held by the team leader is essential to propose innovative solutions to deal with unsurmountable issues of geographical distance and lack of funds; c)Team mind-openness is a key pillar to mobilize artistic skills and the desire to experiment and celebrate the collective confidence in problem-solving; d)Technology and human intelligence can be summed up to bring the “complex reality and social context” to educate foreign individuals to imagine the context of questionnaire application; e)Creative design can be associated with methodological rigor without undermining the seriousness of data collection; f)Creating a questionnaire that could incite reflections and confidence to disclose opinions and experiences by first-time participants implies management skills to deal with unprecedented responses in type, amount, and breadth of information.

4.Formulating Questions to Remotely Collect International Data

The contingent needs to redesign methodological strategies to make the recruitment and data collection feasible in unknown and especially hard-to-reach settings. It was responded to by mobilizing senior qualitative researchers’ knowledge of the philosophical and theoretical standpoints of the paradigms of qualitative research. These experiences, within the constructivist, social interactionism, and complexity paradigms, as well as with the research design of qualitative modelling, grounded theory, and ethnography (Creswell & Creswell, 2018; Morin, 2005), were instrumental to the achievement of inner harmony. This set of experiences allowed them to innovate on methodological grounds while strictly respecting the choice of the most suitable procedures to explore the prospective participants’ scope of experiences, thoughts, and knowledge. Decisions made by those qualitative experienced researchers to respond to a research question and choose data collection tools and methods to collect and analyse data are purposeful. Decisions are embedded in their beliefs and world perspectives, as related to their social reality (Pope & Mays, 2020). It should be kept in mind that qualitative research looks for “understanding human experiences in its unique context” (Doyle et al., 2020; p. 445), and deals with the challenge of translating qualitative questioning into qualitative-inspired questioning. Researchers’ awareness of their own inductive ways of thinking recognizes the dynamics of a phenomenon under investigation as it unfolds in unknown sociocultural settings. Our various experiences concern qualitative-inspired online surveys implemented in a continental sphere (Africa, South and North America, and Europe) with the creation of survey questionnaires for an exploration of participants’ opinions, accounts, experiences, and decisions. This creation was achieved by using an exploratory, non-experimental design. Data analysis was planned to use descriptive statistics and thematic analysis for the small number of open-ended questions inquiring about participants’ opinions, suggestions, recommendations, narratives, etc. (Creswell & Creswell, 2018). The inability to directly contact participants, or participants not having adequate access to social media or distance communication apps-sometimes due to foreign government ban-justified the methodological decisions. Decisions about the design of questionnaires to explore substantial core information to collect data with participants in remote areas. The core intention was to formulate questions within a qualitative research exploratory perspective, considering that the “ongoing process of questioning is an integral part of understanding the unfolding lives and perspectives of others” (Agee, 2009, p. 431). The process of inquiring about the why and how of human interactions, while using questioning as a navigation tool toward possible or unexpected directions, is expressed by the integration of a theoretical perspective inspiring the questions’ design (Agee, 2009).

4.1 Other relevant technical aspects

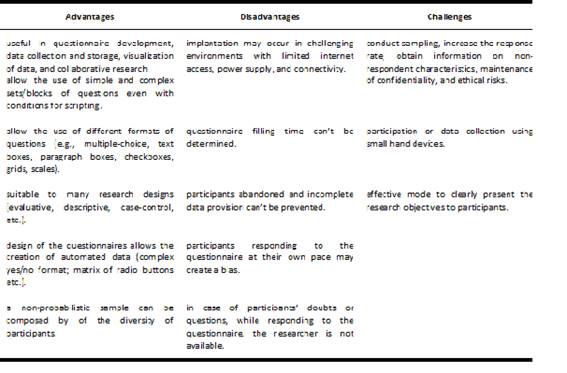

Other technical aspects were respected, such as procedures for the development and validation of measurement tools (Streiner & Norman, 1996). Further basic concepts and recommendations were observed other than those relating to reliability (e.g., concerns with randomized or systematic errors as expected in any measurement tool). We worked with (a) the judgment of relevant domains and ideas to identify what is (almost) accurately appropriate; (b) the validity or confirmation to be supported by assumptions and knowledge held by a panel of experts; (c) the special attention required to surmount the difficulty of establishing reliability in cases with a non-existing scale; (d) the use of previous empirical evidence to guide the choice of items (questions); (e) the consideration for all suggested items by experts to generate a maximum number of items; and (f) the social desirability and pretended well. Furthermore, in formulating questions, a relevant concept is validity, as it refers to what is intended to be measured and the relationships among variables in the measurement tool (Streiner & Norman, 1996). The search for a clear identification of the “what” justified the methodological decision of confirming with participants the appropriateness of work within some linguistic diversity. A frequent approach refers to content validity (Streiner & Norman, 1996), which intends to determine the representativeness of a sample behaviour. It was expressed in multiple-answer alternatives relating to many circumstances, as introduced in the developed questionnaires. In qualitative research, however, validity implies the accuracy of accounts representing participants’ realities of the social phenomenon under investigation (Creswell & Miller, 2000), which could not be observed. Validity also uses the participants’ lens to see their reality and reveals how important it is to have natural experts to corroborate the researcher’s perspective about the phenomenon of interest. The strategy of data triangulation, which refers to the availability of different types of data to enhance such verisimilitude and proximity of reality (accuracy), was used. The search for validity is a relevant step in the development of quantitative scales, despite inconsistencies in the reporting of qualitative methods (interviews, focus groups, Delphi method, consultation with experts, and brainstorming) used to generate new questionnaires (Ricci et al., 2019). In our work, consultation with natural and professional experts was done. For example, a more complete exploration of validity in a questionnaire in the French language, designed to be used within a diverse non-academic Francophone population, is reported Zanchetta et al. in (2018a). The testing included the content validity and evaluation of comprehensiveness, and a test of simplicity and readability. The assessment also addressed the level of readability, the linguistic meaning, objectivity, degree of difficulty, and leading questions (Terwee et al., 2007; Hak et al., 2004). The test of readability and simplicity was corroborated by assessing the semantic and linguistic quality by a test of the simplicity of words called Flesch's readability test (Flesch, 1948). This test measures the level of reading difficulty with the following formula for further interpretation (Townsend et al., 2008; Banna et al., 2010): Simplicity = 206,835 - 1,015 x (number of words ÷ number of sentences) - 86,4 x (number of syllables ÷ number of words). Interpretation of results for the French language was proposed by Timbal-Duclaux (1990) as the following (free translation): score 0-20 = scholarly content; score 21-25 = current content; score 26-30 = fairly easy; score 31-35 = accessible to the general audience; score 35 or more = widely accessible to the general audience. Current warnings in quantitative research regarding methodological issues, such as the need for transparency in reporting, and what Griffiths and Norman (2021) call the replication crisis in science (when only positive results are reported), were observed by experienced qualitative researchers on our team. Attention to methodological sophistication acknowledged that innovation, re-creation, and creativity also characterize . . . research endeavors to solve the population’s problems . . . to be audacious in the exploration of many sources of knowledge to build their own research methodologies, grounded on meaningful philosophical ideas and theoretical frameworks. (Zanchetta, 2021a, p. 2).There is an undeniable link between qualitative research and its focus on the concept’s elicitation and language refinement, as well as the description of attributes and levels that ultimately support the development of the robust quantitative scales (Hollin et al., 2019). It is necessary to add that online research uncovers appealing challenges to qualitative researchers who are required to manage data collection in large settings and develop skills to deal with large amounts of data (Powell & van Velthoven, 2020). It is possible that innovation can be incorporated into new tool designs. This is because the scientific literature on online surveys is growing and rich in advice for good practice, among them those offered by Nayak and Narayan (2019), including some advantages and disadvantages, as well as possible challenges in their use. Some of them are listed in Display 1.

Display 1. Online Surveys “What to Consider”

In sum, the design and development of the original questionnaires for our international research applied the following methodological rationale and procedures: 1 -Acknowledgement of the implicit risk regarding the lack of previously validated questionnaires for use. Such a lack of tools offered the unique opportunity to hear the professionals’ voices as knowers of the clientele, and the voices of clientele who knew their experiences and guided us in the processes of creation, invention, and innovation. 2-Intention to formulate new, stimulating questions for dialogue through the enumeration of many possible answers that could represent the multiplicity inherent to the actions, thoughts, beliefs, and experiences of the prospective participants. 3- Designing original questions inspired by the structure of semi-structured questions for an individual interview or for a focus group by using the tactic of listing all the possibilities of the response, as originated through the knowledge of researchers about the phenomenon under investigation and the findings in a literature review about it, as well as through contact with natural experts who have experienced such phenomena. 4- Exploration of the representativeness of the questions and the response options by always submitting them to a critical review and semantic validations by lay or professional individuals from the same sociocultural context in which the participants lived/worked. 5- Having a bilingual principal investigator and some co-investigators (English, French, Italian, Portuguese, and Spanish) to prevent errors in translation/interpretation and mistakes in semantic attribution to words. 6- Having the research team critically review the meaning of words and their colloquial use in the actual research social context. 7- Conducting a methodological rewording by the research teams, led by a senior researcher in qualitative research with some experiential knowledge (but holding theoretical-methodological knowledge) in quantitative research, thus preventing methodological threats.

5.Renewing a Dialogue Setting

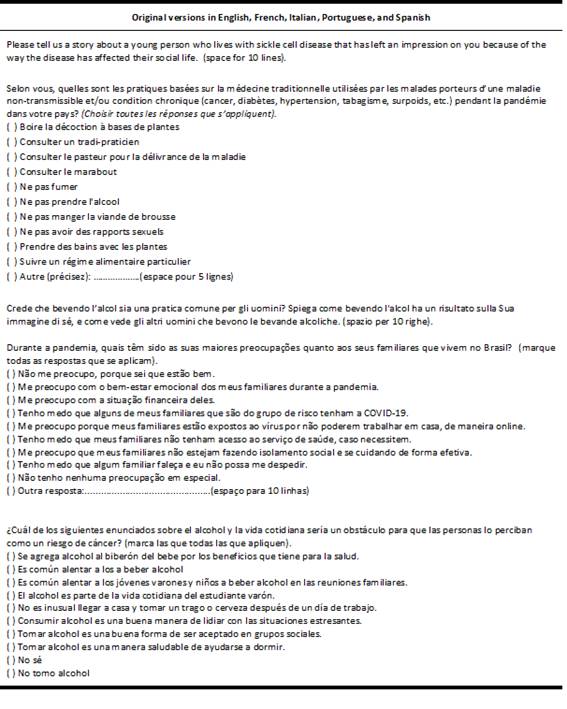

The current movement of conducting data collection on online platforms was expanded by the international and global research conducted by the COVID-19 community of researchers (Lobe et al., 2020). This expansion opened doors to new venues of dialogue between researchers and their target audiences, and particularly to qualitative researchers who pursue reflection about how to creatively and effectively collect data using online platforms, reaching out to many populations (Varma et al., 2021). The current, growing use of online platforms to collect qualitative data provoked concerns about the platforms’ security and the logistical needs of computer equipment (Lobe et al., 2020). However technical difficulty and accessibility to all participants despite their physical, motor, visual, and/or cognitive abilities do exist (Topping et al., 2021). The growing trend is to accommodate the requirement of social distancing and the use of online data collection procedures, among them an online survey (Varma et al., 2021). Noteworthy is the newest and most challenging online work environment, as identified by many others, which has been progressively experienced by some researchers in our team at least since 2014 (Zanchetta et al., 2016a; 2016b; 2018b). Our reflexive examination addressed how to create a setting for a virtual “dialogue” with participants, having the survey questionnaire as a bridge. For example, some relevant recommendations for qualitative interviews, as proposed by McGrath et al. (2019), were applied in the creation of the setting for that dialogue. The situation of a “simulated interview,” and a “metaphorical interview guide” virtual process, undergirded the idea of encountering the participants. The key recommendations followed in regard to (a) the cultural and power dimensions of the “interview” situation; (b) the construction of an “interview guide” and the test of questions; (c) recalling that the researcher is the co-creator of the data; and (d) the allowed adjustment of the “interview guide”. In this work, the rigorous use of a language, its possible inner variety, and Premji’s recommendations (Premji et al., 2020; p. 171) about technical procedures for qualitative research was observed, especially regarding language issues in sampling and recruitment. Some questions are applicable to our work. In relation to sampling procedures, for instance, those questions are (a) from which language groups will researchers compose the sample?; (b) how will the languages be chosen?; (c) what are the benefits and limitations of this sampling strategy? For the recruitment procedure, the main question is: are the language or translation(s) of the recruitment materials appropriate (e.g., dialect, wording)? Display 2 presents some examples of exploratory questions in their original language and formulation, with alternatives of multiple-choice and open-ended questions inciting narrative accounts.

5.1 Use of the Questionnaires

Questionnaires were useful to collect data in different types of international online research. The average time for a survey’s availability on the online platform hosted by Ryerson University (Toronto, Canada) was four months, indicating a slow, continuous adherence by the participants. It is noteworthy to add that bilingual representatives of the Toronto society, who were members of the Ryerson University Research Ethics Board, reviewed all the documents that would be presented to the prospective participants also in a second language. Exploratory online surveys addressed the following topics (number of participants is presented in parenthesis): a)Emotional experiences of Brazilians living in Canada and their families living in Brazil during the pandemic COVID-19. An online survey applied to participants in Canada and Brazil (n= 445) (Zanchetta et al., 2021b); b)Brazilian dentists’ and dentistry medicine students’ sensitivity to social vulnerabilities (n=35; study in progress) (Zanchetta et al., 2021c); c)Health professional practices in Brazil in the area of the humanization of labour and childbirth (n= 389) (Zanchetta et al., 2021d), as well as local society knowledge about national humanization program (= 414) (Zanchetta et al., 2021e); d)Health promotion implementation in schools in Francophone African countries (n= 11) (Zanchetta et al., 2021f); e) Canadian youth knowledge on sickle cell disease (n= 89) (Zanchetta et al., 2021g); f) Men’s sense of masculinity, knowledge on alcohol consumption, and risks for cancer (n= 176) (Zanchetta et al., 2021h); g) Deeds of Francophone African graduates of the Master in International Health and Nutritional Policies (n= 70) (Zanchetta et al., 2018b). Note that surveys implemented in the context of African Francophone countries were less likely to recruit a higher number of participants, despite the large population of health professionals that was reached out to by the local and regional recruiters. Infrastructure issues explain these results; however, the low rate of participation of dentistry participants seemed to be due to the partial observance of instructions to the platform navigation. Another relevant issue concerns the extreme language variations faced in research implemented in French and Portuguese, due to the regional differences of semantic meanings of words in the same country. For instance, in Zanchetta et al. (2018a), it was reported how a team of Francophone researchers from different countries worked together to reach a consensus about the choice of words. The questionnaire was equally reviewed by an elementary school teacher to corroborate the use of plain French that would be accessible to users from different levels of general literacy and education. Zanchettaet al. (2021e) report that the Lusophone researchers located in Canada and Brazil worked to refine many words to allow a questionnaire to be used by professional and lay participants, who originated from Brazil’s five geographical regions with recognized Portuguese language particularities. Overall, within the language context, the use of plain, simple language was strictly applied to the informed consent form as a preamble to introduce the participants to the new discourse and world of research. Technical words and jargon were less used, in order to secure a high level of comprehension and to create a friendly climate of asking-responding, to prevent any form of intimation to the participants. Ultimately, the use of questionnaires translated our team's intentions to respect the participants’ knowledge and make them sure that they were relevant to the advancement of scientific research on the topic under exploration.

Display 2. Examples of Questions.

6.Recruitment, Attrition and Participation

6.1 Recruitment

Access to the target populations was possible due to the well-established collaboration with international professionals and community stakeholders. This helped enormously in the research announcement and recruitment of participants. This was achieved by providing their lists of emails, access to social media groups, online live presentations, and the principal researcher’s introduction to their professional networks, as well as by allowing the inclusion of their names in the recruitment ads. Online recruitment strategies in social media can be considered extremely useful to reach out to a large number of prospective participants within a short period of time. However, these strategies may be extremely impersonal - and less credible - as the researchers are unknown and the universities’ reputations unchecked, undermining participants’ perception of respectable research. Moreover, data collection tools should be friendlier, composed in a simple tone aiming to create some virtual approximation of questions with participants. The formal, structured presentation of a research ad for recruitment with the universities’ and researchers’ credentials and contact information, even from the research ethics committees/boards, may be successful strategies to prevent attrition in recruitment. Once more, collaboration with local cultural insiders who are socially recognized as leaders can be an excellent strategy, utilizing them as appropriate gatekeepers to the unknown population being addressed. Impersonal, indirect, or even no contact between the researcher and the participant may not be well accepted, as the contact between the researcher - who is asking for participants’ willingness to provide answers - and the participant - who may volunteer to answer questions - can be a social expectation or norm. This lack of contact can compromise the data’s fullness in a context in which the participants should be aware of their natural expertise. Participants hold a high level of contribution to the research success based on the opportunity of sharing their experiential knowledge with researchers.

6.2 Attrition

The planning of the methodological strategies since the redesign of qualitative research on online platforms also considered the probability of a failure in establishing such a dialogue, resulting in an elevated loss of participants. To prevent that, we admitted that many participants would access the survey platform and grant the implicitly informed consent, but probably close the browser without being able to return to answer the questionnaire. A subsequent decision was to include additional instructions in the last portion of the online informed consent form. Overall, the participation rate was always high (around 40%, compared to the 17% participation rate reported for quantitative surveys with questionnaires). Moreover, we recognized that the data collection allowed for great ease of participation by individuals who mostly answered the questionnaires using mobile phones, and who could click on options from multiple-choices with the minimum typing requirement.

6.3 Participation

One of the relevant, unpredictable issues faced in all implemented research was the difference between the amount of access to the informed consent form with a positive response informing the decision to participate, and the actual number of completed questionnaires. Mitigating the possible explanations is beyond the researcher’s control. The use of online questionnaires brings forward two relevant issues that threaten the effectiveness of the recruitment process. First, by accepting to participate, the participant may decide to return later to the platform, after having read the instructions for responding to the questionnaire, which may imply a moment of forgetfulness and result in the loss of a participant. Online platforms may not partially save the responded questionnaires or allow for the return of the participant once the browser is closed. Both situations may be frustrating to participants, leading them to give up their participation (Topping et al., 2021). Second, as stated previously, when the researcher is barely known or unknown to the participant, some distrust may occur. Prospective participants may have doubts about the researcher’s and online research’s suitability, resulting in a decision to not participate. Moreover, an unknown researcher exploring a controversial topic may raise some conflict of interest, particularly when evaluative research tends to challenge the status quo. It is noteworthy to say that in all implemented online research, information about the participants’ computer IP and their personal email remained inaccessible to the principal researcher. Despite this information being presented in the online informed consent form, it may not secure trust among the research team and prospective participants and undermine their confidence to participate. In other words, an effective participation rate can reflect a degree of trust that the participants hold regarding the researcher, as well as their reactivity to the nature of the questions themselves. The aforementioned issues can be significantly attenuated by the in-site support provided to the online and person-to-person recruitment by many social actors (who sometimes are unknown to the research team). These social actors, once stimulated by team efforts to implement online research, do decide to help. In many cases, this extra community strength culminated in undeniable success.

6.4 Unpredictable Contexts and Situations

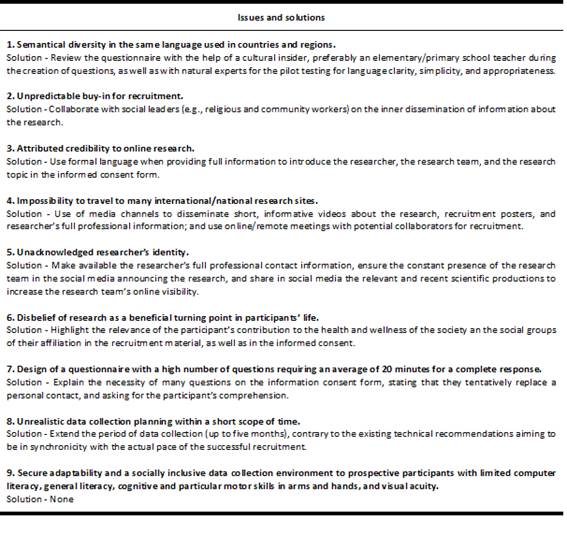

Researchers will never be able to affirm that their participation was fully confidential despite the observance of all ethical principles and the emphasis on the need for aural and visual privacy by participants. It refers to the use of an online implicit informed consent form with authorization to participate and has data collected as a precondition for participation. Research fieldwork in low- and middle-income countries can be constantly at risk due to the instability of internet connections and restrained access to many websites, as determined by local governments. Researchers can be unable to secure good internet connections (e.g., internet speed, sound and video quality) that generally are related to the limited financial resources of local organizations. Therefore, the impossibility of identifying participants’ location makes any form of support, such as financial support for connection fees provided by local community stakeholders, unfeasible. Moreover, poor or unstable internet connections may cause the interruption of participants while responding to questionnaires and a difficulty to return to webpages or platforms, with a subsequent loss of data and participants’ discouragement to return to data collection sites. Display 3 introduces the high impact unpredictable and challenging issues faced in the fieldwork (before and during) to which solutions were implemented. It is necessary to clarify that Display 3 presents some solutions (items # 1, 2, 6, and 8) that are equally applicable to online and offline quantitative and qualitative research. Based on our field experience those solutions are crucial for successful recruitment and data collection.

Display 3. Fieldwork Matters.

7.Final Considerations

This report presented some successful experiences of internationalization of quantitative online surveys and intellectual partnerships. This success occurred in the process of creating, exchanging, and translating knowledge in the context of global health and the democratization of knowledge. Using the internet to overcome geographical distances and connect researchers interested in exploring life and health experiences with many populations giving voice to all, is undoubtedly to be considered. This type of work strategy can strengthen international intellectual collaboration, leading to new developments in research in the global context. Current limitations of research fieldwork during the pandemic require special attention to the time availability of professionals to respond to online surveys, due to the intense work pace. Moreover, a certain “research fatigue” is already identified, mainly by front-line health workers, despite researchers’ increased interest in learning and documenting this population’s experiential learning, accomplishments, deeds, criticisms, intellectual industriousness, and awareness. It is necessary to say that researchers and university teachers have also been invited to participate in online surveys. Requests refer mainly to national and international surveys about new teaching online and remote strategies, as well as data collection for Master and PhD students’ research. This global trend corroborates the emerging popularity of international online surveys, applying a variety of designs (quantitative, qualitative, hybrid, and mix-methods), and showcasing many examples of creativity in the design of their questionnaires. Such “research fatigue” deserves more attention and should be a matter of further reflection among researchers and educators in graduate programs. On the other hand, in some contexts, online surveys remain the less intrusive design to reach out to the prospective participants, acknowledging researchers’ difficulties to enter the many settings of practice to conduct direct research fieldwork. A relevant note refers to the fact that the development of the internet in Western Africa is likely to improve the feasibility of such research. For example, a few years ago, it was very difficult to have a telephonic conversation with a co-researcher (or any other local individual) and exchanging only one email could take one day. The cost of internet connection fees, once only accessible to big companies, is now possible for individuals. Communication is widely available due to many factors: (a) the development of optical fibers by international communication companies; (b) the financially accessible price of tablets and mobile phones to a much wider public due to the development of e-health tools, mobile or smart health; and (c) the increased use of technology for e-learning. All those improvements will allow for the development of more user-friendly interfaces in our future research and the use of more sophisticated and even validated questionnaires. Better access to remote and online technology will contribute to improved recruitment and a better experience for participants, and therefore more adherence to research. The improvement to the feasibility of remote collaboration and the process of building and consolidating global research teams makes it a reality to bridge researchers located in low-, middle-, and high-income countries. Facilitating conditions include the availability of coworking platforms, and the possibility of clarifying questions with remote co-investors through a phone call made with an app (it is becoming common to converse, from North America or Europe). Altogether, such developments will ease the questionnaires’ validation with individuals living in the targeted countries and avoid miscomprehension that could jeopardize-and ultimately compromise-the methodological rigour and quality of implemented research in global collaboration. The risk management of such online research will be improved, as well as the quality management and improvement. The actions of universities with such an avant-garde vision of connecting countries through knowledge mobilization and exchange, such as the Digital Francophone International University (Université numérique francophone mondiale) (Leroux et al., 2013), is one of the most promising avenues to promote buy-in among the global community of researchers. Current concerns about the effectiveness of collaborative research networks are equally important, as commented by Leiteet al. (2014). Proposed indicators, such as leadership power, the intensity of collaboration, and network action (publications, research groups, universities-affiliated authors, research foundations, etc.), can identify the modus operandi as expressed by size, reach, and dynamics. In the creation of a knowledge production network, Pugh and Prusak (2013) emphasized that online-based collaboration has distributed knowledge with low cost and shortened greater geographical distance. Among the proposed strategies, the aiming for social inclusion and high community participation is of particular importance for those in global health. These emphasize the purposeful action of building collaboration with individuals aware of the attributed value and using the following factors: (a) the profile of a member, different profiles for different levels of participation; (b) the search for intentionality; (c) the level of comfort with ambiguity; (d) the level of commitment; (e) the search for both individual experts and those with strong networks; and (f) the profile of the collaborators who can be self-starters and/or team players. Those interested in improving the quality of life and health of populations that deserve our attention and intellectual investment are equally invited to review collaboration for research at all possible levels. Researchers are invited to redesign new ways of mobilizing popular knowledge by collecting it. Increased dialogue with natural experts can be possible using many forms of technology profiting from the undeniable value of social media. These experts can be members of the professional communities, political stakeholders, and community leaders. In the end, this will make it possible to envision that global health will dramatically improve. For that, online surveys can be extremely useful tools. The main expected contributions of the chapter refer to the proposed solutions to support the rigorous research fieldwork with the use of online methods and techniques. Contributions are suggested that could help other researchers in a wide globalized academic ecosystem to overcome technical, contingent, and unpredictable issues. The research fieldwork could be full of challenges and pitfalls, but the cultural humbleness held by researchers as global citizens interested in responding to trends and perspectives of knowledge generation should not be neglected. Recommendations for future research follow. The first is from the participant’s point of view: a methodological exploration of the questionnaires’ questions and response options allowing for participants to consider multiple ways to recall experiences. Such recall could include the most appealing feature evoked by the questions, as well as the rich array of guiding thoughts for the participant to choose options representing the course of action, ways of thinking, decision-making, and so on. The second is the utilization of qualitative research to investigate with participants who had participated in this type of online survey, their perceptions about the created dialogue and proximity with the researcher. It can address the “setting” where the dialogue takes place due to its mental elaboration as provoked by a high number of options of responses to reflect on. Such research certainly could document the emotional and affective context of indirectly dialoguing in a “blind” way. The ultimate goal of these recommendations is to inform researchers that a quantitative descriptive online survey is also able to give voice, provoke discourse and awaken awareness.