1.Introduction

The World Health Organization declared Covid-19 a pandemic on March 11, 2020, as announced by WHO Director-General, Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus (World Health Organization, 2020). This pandemic has affected the entire world in an unprecedented way and has impacted many aspects of our daily lives. Research development has not been exempted from the impact of COVID-19 restrictions, unless the research was related to COVID-19. For instance, researchers have faced delays in implementing the many steps of their research, from reviews and approvals of the Research Ethics Board to data collection and dissemination. Also, prioritizing Covid-19 related manuscripts has relegated research through peer- reviewed publications to a low rung.

Since March 2020, researchers have become flexible and innovative to make sure they continue to meet their commitment to contributing to scientific evidence. For example, they have been adjusting research methods and procedures to ensure compliance with social distance to maintain researchers’ and participants’ safety. These commitments have contributed to increased use of online platforms, especially in qualitative studies where researchers need to connect with participants for data collection that usually involves face-to-face recruitment and interviews. Researchers need to include in the research plan the strategies they would use to comply with COVID-19 restrictions and submit these strategies to research ethics boards. Otherwise, their research protocol would not be approved and further delay the process. Such requirements correspond to our experience in implementing qualitative research, particularly including grounded theory methodology. On the other hand, while using online strategies as an alternative for data collection in grounded theory, it is important that researchers reflect on the impact and effects of the changes in the operationalization of the studies. For example, it is imperative to ensure that the research plan will be able to capture the essence of the meaning, actions, and reactions researchers are looking to explore and the processes to be uncovered in grounded theory studies.

Importantly, most data collection in grounded theory involves the researcher being immersed in participants’ experiences to understand and uncover the processes and context affecting it. In constructivist grounded theory, for example, it is important that the researcher use flexible and exploratory strategies to understand the multiple social realities that participants face (Charmaz, 2000). During the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic this presents a challenge, since it may prevent researchers from collecting enough data without meeting participants in person. A face-to-face interaction benefits researchers not only because they can observe body language to understand reactions, motivations, and actions, but also because researchers can be very attuned to facial expressions and silence. Such an iterative process often benefits from more them one encounter with the participants (Charmaz, 2014).

Furthermore, symbolic interactionism, the theoretical perspective or philosophical underpinning of the Straussian and Charmaz version of grounded theory assumes that interaction is inherently dynamic and interpretive and therefore addresses how people create, interpret, endorse, and alter meanings and actions in their life (Charmaz, 2014; Oliver, 2012). This interaction will provide researchers with an opportunity to take a deep dive into participants’ experience and together co-create meanings, and interpret action and interactions participants take in their daily lives (Oliver, 2012).

Therefore, by marrying grounded theory and symbolic interactionism together, researchers may uncover, understand, and explain the phenomena in which participants are immersed. When researchers implement grounded theory in times of a pandemic, they must acknowledge and disclose any modification in the data collection strategies and the impact this modification may have had on the operationalization of the study, both on themselves as well as participants. Thus, the purpose of this paper is to share our experience in conducting grounded theory studies during challenging times such as this current Covid-19 pandemic. Particularly, we describe the benefits and challenges of recruiting participants and collecting data through virtual interviews. Then, we follow with recommendations to overcome the challenges and ensure trustworthiness and rigor when implementing virtual strategies to conduct grounded theory studies.

2.Grounded Theory Methodology

Grounded theory methodology provides an explicit method for analyzing processes. These processes consist of unfolding temporal sequences that may have identifiable markers with clear beginnings, endings, and benchmarks in between. In such a process, single events become linked as part of a larger whole (Charmaz, 2014; Bryant & Charmaz, 2007). Therefore, researchers willing to understand and provide a theoretical explanation of a phenomenon of interest must formulate their research questions to unfold and make this process more explicit. They must also understand the context in which participants are immersed because that may affect the process being discovered. For example, the first author (first author) used constructivist grounded theory to explain the processes of engagement in self- care management for individuals with diabetic foot ulcers and to identify the contextual factors influencing their engagement (Costa at al., 2021). The second author is using constructivist grounded theory to understand the processes of social norms formation among nursing groups. The author will examine how nurses’ day-to-day practices and the context in which they are immersed influence social norm development and their decisions to stay in the profession. To be able to capture the processes and context the researcher will need to engage in reflection pay attention to the effect of the changes in the operationalization of the studies (e.g., use of virtual platforms for data collection).

In summary, to be able to understand the process and its steps (temporal sequences), researchers using grounded theory methodologies need to rely on robust data gathered from participants’ experiences and their social world. Researchers also rely on written and recorded information from the interview, engage in interaction with participants the during interview, and write fieldnotes and memos (researchers’ reflection, analyses, and decisions made in developing data categories) (Charmaz, 2014; Charmaz & Thornberg, 2020). Grounded theory requires researchers to be immersed in abstractions within the data and in an iterative and simultaneous process of data collection and analyses. These dynamic processes allow the researcher to dive deeply into the data and come up with new inquiries for exploration by asking further questions of the data and then returning to participants to clarify and validate their understanding as well as the categories and concepts that emerge from the data (Charmaz, 2014; Corbin, 2017). For the first author, the repeated processes of moving back and forth between the data were essential to the development of theoretical categories and concepts and to achieve the goal of unfolding the temporal sequences of the theory. In the next section we will discuss the significance of the interview to the knowledge generated in grounded theory research and how to shift this knowledge to a virtual platform in times of a pandemic.

3.Data Collection in Grounded Theory Research: The Significance of Interviews and Field Notes

In general, interviews are the backbone of grounded theory studies. The most recommended and popular way of implementing this research procedure is by meeting in person and face-to-face with research participants. This procedure is seen as one of the best approaches to collecting multiple levels of data, allowing the researcher to identify data that is non-verbal, contextual, and interpersonal while allowing the interviewer to be receptive to participants’ questions and responses (Brinkmann, 2018; Charmaz, 2014). In our experience, having an interview guide with broad (open-ended) and non-judgmental questions enables researchers not only to explore the process related to their topic, but also to move to another topic after participants’ have already answered a relevant question. Open-ended questions also encouraged unimagined statements and stories to arise. For instance, a significant number of participants in Costa’ s 2018 study stated that they were surprised at how many things they could recall from their experience of living with and taking care of their diabetic food ulcer (DFU). While others did not provide enough detail of their experience in taking care of their wounds, they focused mostly on the personal struggles in navigating in their social world with diabetes and DFU or on the impact of DFU on their lives. Charmaz (2014) states that the combination of how questions are constructed and conducted help to achieve a balance between making the interview open-ended and focused on significant statements.

It is also recommended that the researcher write field notes following each interview to record their reflections and what they learned during their conversation with participants (Strauss & Corbin, 1990, 1998).

Field notes enable researchers to document their impressions and reactions about participants’ experiences, as well as systematic questioning of pre-existing ideas related to researchers’ previous experience and what participants said or responded to during the interview (Strauss & Corbin, 1990, 1998). Field notes is seen as additional form of data collecting, where the researcher use it to document important descriptions of data such as date, time, actions, behaviors, and so on. For example, in Costa’s study the first author documented the type of shoes or offloading devices worn by participants as well as side conversations (Costa et al, 2021). These documentations were most likely possible because the interview occurred in person and the researcher had visual access to the environment. On the other hand, if researchers are using online means to collect data (e.g., phone call, videoconference) they must be aware that this could affect collection of rich and detailed field notes. For instance, researchers may not be able to see the entire environment, body language of participants, side conversations, or persons walking around in the same environment as research participants, which could create distraction and affect the comfort of participants to share the information required.

4.The Impact of COVID-19 on Grounded Theory Studies

The COVID-19 pandemic has forced scholars to adapt to a new way of conducting research. Although challenges related to research implementation arise while maintaining social distance, benefits also emerge that may continue to be used post-pandemic. Challenges affecting the implementation qualitative research include recruiting participants, conducting interviews, and writing field notes while protecting participants and researchers. Benefits of conducting online research include cost saving related to travel for both researchers and participants, comfort to the participants in their ability to choose where they take part in the interview (their own home, office), the ability to see the participant and identify non- verbal communication, and a decrease in barriers to scheduling interviews (Sah, Singh & Sah, 2020).

To date, no publications have reported the challenges and benefits of conducting grounded theory studies during the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, we describe our own experience in conducting grounded theory studies during this challenging time. We also use publications from authors who implemented different methodologies that also used virtual data collection, which we understand to be transferable to grounded theory studies due to their similarities with data collection sources. In the next sections, we summarize the benefits and challenges/limitations of using online strategies to collect data in grounded theory and finalize with recommendations for future research.

4.1Participants’ Recruitment through Online Means

The second author, who is currently conducting a grounded theory study during the Covid-19 pandemic, has experienced some challenges as well as benefits. Challenges in recruiting participants have resulted in submission of amendments in the study protocol to the Research Ethics Board (REB) and to request other sources of recruitment that have delayed the study. Due to not being able to do an in-person recruitment session to explain the study and answer potential participants’ questions, the second author sought support from the administrations of research’s institutions to access nurses by sending recruitment emails with information about the study, but this strategy did not work. After talking to many researchers and colleagues in our network who have utilized this strategy for recruitment and found that people are becoming more comfortable with online communication platforms, the second authors have decided to give it a chance. Therefore, an amendment was submitted to the REB with a new recruitment strategy that include social media such as Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp and word of mouth. Over a couple of days of implementing this change in recruitment strategies, the author was able to recruit over eight participants who met the research criteria and agreed to provide an interview via Zoom platform. Over a longer term, this strategy coupled with word of mouth (or snowball sampling technique) has helped the second author to recruit over twenty participants to the grounded theory study, which has met the criteria for achieving theoretical saturation.

In fact, the use of social media as a strategy for recruiting research participants was initiated pre COVID- 19 but has now become more popular than ever. For example, Kasymova et al., (2021) conducted a mixed method study to document how the pandemic has affected academics who are also mothers. The mothers were recruited using a specific group on Facebook that identified themselves as “Academic Mamas”. This Facebook group had 11,226 group members, including the two authors of the study.

The authors posted an invitation and the research criteria to recruit potential participants to access the questionnaire/survey during a two-week period. A total of 131 participants who met research criteria agreed to complete the survey (quantitative part of the study). Participants who met the research criteria were invited to a follow-up interview (qualitative part of the study) in which 20 participants agreed to take part via phone, Zoom or Google voice to more deeply explore their experiences.

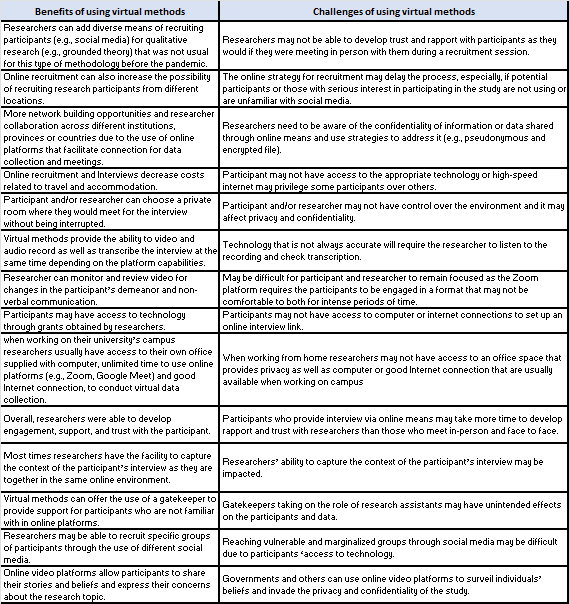

Nowell et al., (2021) conducted a grounded theory to explore nurses’ process of coping during COVID-19. They used social media posts, emails, and word of mouth to invite/recruit participants from various countries and clinical settings during the topmost aspects of the first wave of the pandemic. The first phase involved asking participants to respond to a survey that helped the authors to identify those who met the study criteria. Theoretical saturation was met after data from a total of 20 participants were analyzed and revealed no new information. Unfortunately, the authors did not report any challenges or benefits of using this method. However, they highlight that they were able to recruit and interview participants (via Zoom) from various countries. Table 1 provides a summary of the benefits and challenges of conducting virtual recruitment in grounded theory studies.

4.2Benefits of Conducting Virtual Data Collection in Grounded Theory

Before the current pandemic, researchers have used alternatives such as online virtual platforms to collect data in place of face-to-face interviews (Archibald et al., 2019; Foley et al., 2021). These alternatives have gained popularity during the pandemic due to the need to maintain social distance and ensure participants’ and researchers safety (Sah, Singh & Sah, 2020). Online data collection such as virtual interviews can also provide some benefits to both participants and researchers, especially related to convenience and cost saving with traveling. For example, collecting date online can decrease research costs and increase access for participants who would require long travel times and possible accommodation (Sah, Singh & Sah, 2020).

The use of online platforms to collect qualitative data were also used during COVID-19 by researchers who needed to adapt their research plan and finalize their studies. For example, researchers of an ethnography study conduct online interviews with ten young environmental activists. The authors published a matrix of challenges and opportunities for researchers and participates (Arya & Henn, 2021). Similarly, authors of another qualitative study conducted narrative interviews using an online platform (i.e., Skype) (Carreri & Dordoni, 2020).

Zoom technology offers cost-effectiveness, as many universities have access to this platform and make it available to all faculty, researchers, and students. Archibald et al., (2019) found that in their study 69 percent of researchers and 44 percent of participants preferred using Zoom compared to in-person interviews, telephone, or other videoconferencing platforms. Participants felt comfortable with this platform because it was the one, they were using in their institution. Additionally, they liked the simplicity of the platform, the ability to build rapport, and easy access simply by clicking on the link to connect with researchers. Participants using Zoom in our grounded theory study interviews during the COVID-19 pandemic have found the platform convenient and easy to use.

Researchers and colleagues have shared with us that using the Zoom platform enables them to observe non-verbal communication, especially if participants are requested to not be too close to the camera. Participants can also respond in real time to researchers’ questions, facilitating engagement, building trust, and supporting conversations. Some participants stated that they would have liked in-person interviewing if it was available, while half of the participants and researchers liked the convenience and cost saving if travel would have been required rather than using the online platform. Using Zoom may have contributed to reaching out to participants from different countries and institutions (Nowell et al., 2021).

In a study in Italy during the Covid-19 pandemic, Arcadia et al. (2021) chose to use the voice over internet protocol system (make and receive video calls over the internet such as Skype) instead of face-to-face interviews due to pandemic restrictions. This interpretive phenomenological study asked twenty nurses about the impact of working during the Covid-19 pandemic. The study used voice over Internet protocol to conduct the interviews, which allowed not only for video communication to be observed for nonverbal communication, but also for the researcher to demonstrate empathic listening.

The authors found that this technology worked well as it allowed participants to choose the time and place, they were most comfortable with to take part in the interview. The nurses were also familiar with using technology and felt comfortable with the online platform. This strategy seems to be also an alternative for collecting data for grounded theory in times of pandemic, as this methodology requires a deep understanding and interpretation of the phenomenon of interest through description and analysis of actions, reactions, and interactions.

In some research studies a research assistant was able to connect with the participants before their online interview to support them in becoming familiar with the platform. Participants reported feeling more comfortable in the interview when they had been shown previously how it would work (Chew-Graham, 2020). In a study examining the experiences of children and youth during Covid-19 a gatekeeper obtained informed consent from the children and one of the parents or legal guardians, a requirement for any participant under the age of 18 to engage in research (Cuevas-Parra, 2020).

Lawrence (2020) reflected on their experience of conducting research during the COVID-19 pandemic that we believe to be transferable to grounded theory studies. The author wrote that researchers must remain open, adaptive, and reflective regarding their use of strategies for operationalization of qualitative methodologies and that rich data can be collected through modalities other than the standard face-to- face interview. The authors highlighted that using online modalities for data collection and interviews may be difficult especially between cultures, countries, time zones, and the laws of each country (Lawrence, 2020). We acknowledge that depending on the topic to be explored and the need for immersing with the phenomena being studied online strategies may not be the most beneficial to utilize. Therefore, the researcher will need to engage in (unwritten) reflection to question what online/virtual modalities of data collection would be suitable to ensure in-depth data collection and come up with a research plan that describes the operationalization of the many steps of the study. Table 1 provides a summary of the benefits and challenges of conducting virtual data collection in grounded theory studies.

4.3Overcoming Challenges While Using Virtual Strategies for Data Collection

In this section we aim to describe the challenges of conducting virtual grounded theory studies during the COVID-19 pandemic and strategies to overcome them. Some of the challenges (Table 1) include building relationships and trust between researchers and participants, supporting rapport, access to participants through online recruitment, spontaneity in sharing their experience during virtual interviews, observation, identification of non-verbal words, the need for gatekeepers to support participants with technology, cyber security, and the mental health of the researchers and participants during the pandemic to be able to build relationships and get the most from their online encounters (Arya & Henn, 2021; t’Hart, 2021; Lawrence, 2020; Meherali & Louie-Poon, 2021; Sah, Singh & Sah, 2020; Weissman, Klump, & Rose, 2020).

Challenges outlined by researchers who have recruited youth participants to their research may be different from those who have recruited older adults. While youth have been used with online platforms and technologies, older adults may not have the experience with digital technologies to connect with the researcher and may identify it is a barrier to participation. Researchers who engaged youth participants in their study found that using online platforms and building online networks offered more opportunities to build trust, relationships, online activism, and networks (Arya & Henn, 2021). Therefore, researchers doing online interviews with older adults may need to provide a gatekeeper to support them with the technology.

Gatekeepers provide support for research participants with technology either directly or in supplying the appropriate technology to participants. Weissman, Klump, & Rose, 2020 identified the idea of a gatekeeper or individual already associated with participants to collect data at the site and send to the researchers as a strategy for continuing research studies through such online platforms. While using a gatekeeper may help to recruit more participants who would be concerned with their ability to use online technology, Sah, Singh & Sah, 2020 have pointed out the need to ensure that they do not take on the role of research assistant or affect confidentiality and privacy.

Ensuring confidentiality and privacy during online interviews presents a challenge different from in-person interviews where the researcher is in charge of finding a private room for the interview.

During the online interview the researcher does not have control of the participants’ environment, which may allow for others not involved in the research to be privy to the interview (Meherali & Louie-Poon, 2021). Another concern to be aware of is conducting online interviews with research participants from places such as China where governments restrict and surveil their citizens. In such a situation, participants may rush to finish up the interview sooner and provide only superficial information if they are likely to feel intimidated by the possibility of being identified. This situation may lead participants to feel uncomfortable answering questions if others are around such as in a household or in other contexts constricted by availability to Internet access (Meherali & Louie-Poon, 2021). In such situations they may not disclose sensitive information that would have been revealed in a private face-to-face interview. It is important to discuss this situation with participants prior to beginning the interview and help them to identify a place, date, and time in which they will be able to engage in a private environment to share their experience. Likewise, it is also important to identify risks related to their participation before beginning the research but to stay cognizant as the research progresses (Lawrence, 2020).

Another reason for concern is that using online platforms for to collect data through interviews may privilege some participants over others. For example, authors of a previous qualitative study described that while some of their research participants had their own smart phones and computers, others had access only to a personal phone which they were also using for schoolwork and did not have data plans to support extra online activity (Arya & Henn, 2021). In our own experience a challenge in using online platforms such as Zoom and Google meet while conducting grounded theory studies included the need for both participants and researchers to have access to high-speed Internet and be comfortable with speaking with each other through a video monitor.

Ultimately, the ability of the researcher to develop rapport and closeness with participants and deeply listen to them during the online interview process to understand the multiple layers of meaning, uncover their context, capture their body language, and take field notes may be seen as limitations to collecting online data in grounded theory studies. For instance, most of the time online platforms only allow for a portrait vision of the participants, thus losing the body cues interviewer and interviewee would normally be aware of. On the other hand, normal silences in conversation may be difficult to capture via the online platform because audio permits only one person to speak at a time, so the participant would finish and then wait for the interviewer to respond, making the conversation seem unnatural (t’ Hart, 2021). Other authors also stated that “one of the limitations of the online platforms is the lower degree of intimacy and closeness between interviewee and interviewer” (Carreri & Dordoni, 2020, p. 828).

Therefore, we recommend that researchers ask participants to position the camera at a distance that will allow the capture of their whole-body image while talking naturally with the researcher. Participants should sit in a comfortable chair, be relaxed, and a find a comfortable position that will help them be as natural as much as possible. It can be a challenge for some participants in the beginning, but as they get used to it, being comfortable will allow them to use body language and help researchers to take note of their reactions and non-verbal messages such as silence and suspiration.

Conducting online interviews also poses a challenge to researchers in recording fieldnotes and how the record will impact the final analysis of the data because researchers cannot see the entire context of the participants’ environment (Meherali & Louie-Poon, 2021). In our experience, recording field notes during the interview has been very important, as mentioned and exemplified above. Therefore, we recommend that during online interviews, researchers try as much as possible to record on their field notes observations and reactions of participants from the start of their connection. For instance, note if participants had difficulty in connecting on the online platform in the beginning and if this provided any interference in their capacity to relax and be themselves during the rest of the interview. Every interference should be recorded during online interviews in the same way as in person.

5.Ensuring Trustworthiness and Rigor of Grounded Theory Studies

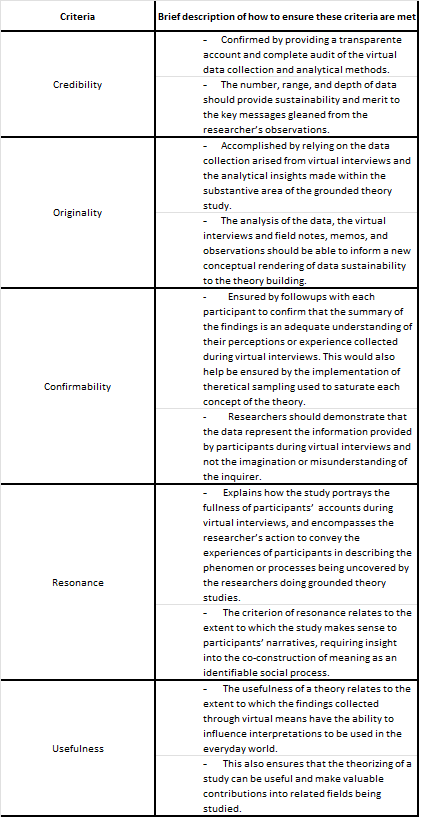

While conducting research in times of pandemic and developing a research plan researchers should keep in mind the standards and criteria to ensure the usefulness and quality of the final work. The five criteria suggested by Charmaz (2006) to appraise the quality of grounded theory should be applied to any research plan regardless of how it will be implemented (in person or virtually). These criteria include credibility, originality, confirmability, resonance, and usefulness (Charmaz, 2014).

While it is the reader who judges the quality of the work, it is also recognized that a strong combination of credibility and originality would enhance the resonance and usefulness of the final research report (Charmaz, 2014). Consequently, transparency and trustworthiness should be followed when adapting the research plan during times of pandemic. These are paramount to allow researchers conducting either in person or virtual grounded theory to be transparent and allow future application of the grounded theory study in its specific substantive area. Table 2 presents an overview of the five criteria described by Charmaz and adapted by the authors to ensure trustworthiness and rigor of studies conducted in times of pandemic.

6.Moving Forward

As with all research, the safety of both the participants and researchers are paramount. This has also been seen over the course of the Covid 19 pandemic as researchers have been flexible and innovative in maintaining the tenets of ethical research practices regarding to the safety of participants. A concern we want to bring to researchers’ attention is related to the effect of the changes in the operationalization of the studies. Observing Covid-19 protocols may impact the many steps of research implementation, including the ability to collect robust and meaningful data. For example, moving to online strategies may affect recruitment of research participants and influence the quality of data collection. Therefore, researchers should describe and provide examples of how they ensured usefulness and quality of the study when conducting grounded theory methodology in times of pandemic.

Therefore, during these unprecedented times of the COVID-19 pandemic, we recommend that researchers create a realistic plan to support implementing the many steps of recruitment and data collection. This research plan should include virtual strategies to recruit participants and offer different methods to collect data. The researcher should consider how to ensure participants’ safety and therefore implement protocols to ensure physical distance. Some possibilities include requesting the administration of the institution to send an email invitation to potential participants, posting research advertisement information on social media, and using the power of word of mouth. The same method would be applied to facilitate access to data collection through virtual means (e.g., via phone, video conference). The research plan should be discussed with all members of the research team and if any questions arise, they should be forwarded to the REB contact person for clarification before submission of protocol. This would save time and ensure that the research plan is compliant with the ethical principles for research with humans.

As the pandemic endures, it is important that researchers are aware of the challenges of conducting virtual grounded theory studies. Considering that educational institutions have incorporated online technology for teaching and learning, it is likely that research fieldwork and the dissemination process will also endorse this trend. Looking at the benefits of using virtual communication tools for conducting qualitative interviews, many researchers are likely to adopt this technique during and post pandemic to overcome time constraints and the financial burden of the research process. If researchers appropriately address the challenges of virtual communication tools, they are likely to prefer virtual interviewing methods rather than an alternate option. Alternatively, researchers may decide to use a hybrid method, which increases the possibility of expanding the sample groups from a global perspective. The pre- recruitment could be conducted virtually by to inviting potential participants to answer questions related to the research criteria and demographic characteristics. Whereas in-person data collection could be used for interviewing those who met the research criteria a priori.

7.Final Considerations

This article contributes to improve our understanding of the benefits and challenges of conducting qualitative studies, including grounded theory, during times of a pandemic. It highlights ways of overcoming the challenges of using virtual strategies for data collection that can impact researchers’ ability to hear and understand the multiple layers of meaning and uncover the context in which participants are immersed. In a research paradigm such as that of grounded theory which involves collecting robust data to inform categories and saturate concepts, using in-person, face-to-face interviews has already proved to be an essential instrument of research to facilitate interaction between researcher and participants.

In moving to online strategies, the researcher needs to engage in a deep reflection about the ability of this strategy to capture the essence of the meaning, actions, and reactions they are looking to uncover and explicate. In summary, while online platforms for conducting virtual interviews have many advantages, they remove the layer of meaning between two individuals’ bodies, which affects the researcher-participant relationship and thus their ability to develop rapport, intimacy and closeness with each other.

Additionally, the final research report should include the impact that the virtual/online means used for recruiting research participants and data collection had on capturing the essence of the phenomena, and how the trustworthiness and rigor criteria were ensured in their grounded theory studies conducted in times of pandemic. Finally, it should also include information about the limitations and challenges encountered and addressed during the study’s implementation.