1.Introduction

Effective, safe, and equitable healthcare and social services systems should reduce the social and economic burdens resulting from ill health and enable well-being. However, an individual’s socioeconomic position is a major factor that can complicate access to healthcare and social services (Angus et al., 2013; Woodgate et al., 2017). In 2018, Canada’s population was 37 million, of which 1.9 million adult women lived on a low income, leaving them vulnerable to various inequities (Canadian Women's Foundation [CWF], 2018). In Canada’s most populated province, Ontario, women are commonly employed in minimum wage jobs, assume the majority of unpaid care work, and face a substantial wage gap compared to men-all of which contribute to their low-income status (Lee & Briggs, 2019). Women who live on a low-income experience exclusion at social, political, cultural, economic and institutional levels, substantially limiting their full participation in society (Kiani et al., 2016; Lange et al., 2014; Marshall et al., 2021; Socias et al., 2016). Combined with limited social networks-which tend to be smaller, limited, localized and insular among women living in poverty versus their higher income counterparts (Drobruck Lowe, 2012, p. 2)-they can suffer detrimental effects to their overall health and well-being (Chan et al., 2018; Lombardo et al., 2014), and encounter substantial systemic barriers that decrease their capacity to make decisions (CWF, 2018).

Women living with lower income, less education or lower occupational skill levels tend to be less healthy than their peers who have advantages in these areas (Hosseinpoor et al., 2012; Wanles et al., 2010). These social determinants of health (SDH), and their associated inequalities, are frequently described as the root cause of health inequities (Braveman & Gottlieb, 2014); yet, there is a paucity of information about how gender and income, as SDH, interact to perpetuate injustices that further create major health inequalities within populations (Social Determinants and Science Integration Directorate, Public Health Agency of Canada, 2016). As such, understanding women’s lived experience of living on a low income and its relatedness to access to healthcare and social services in the Canadian context is important. Our study is about working in partnership with women in the city of Kingston, Canada, to elevate their voices and to work toward finding sustainable solutions and making change, however small, that is right for them as they determine it. In this paper, we present preliminary results from semi-structured interviews of our study about understanding how gender and income influence access to healthcare and social services for women living on a low income.

2.The Social Determinants of Health Framework

Our study, including the thematic analysis, is guided by the SDH framework described by Loppie-Reading and Wien (2013), who categorized the determinants into proximal factors (e.g., health behaviours, physical environments, employment and income, education, and food insecurity), intermediate factors (e.g., healthcare systems, community infrastructure, resources, and capacities) and distal factors (e.g., racism, social exclusion). Researchers have found eliminating poverty would be the most significant determinant of health, as having enough income allows for purchasing and obtaining the other determinants of health, such as adequate housing, nutritious food, education and access to health and healthcare services (Braveman & Gottlieb, 2014).

3.Description of the Study

3.1 Study Design

Our qualitative study follows a combination of participatory action research (PAR), art-based research (ABR), and hermeneutic phenomenology approaches to examine how gender and income affect the experiences of access to healthcare and social services for women living on a low income. PAR is a collaborative approach where there is an equitable partnership between academic researchers and community stakeholders (Hacker, 2017; Oetzel et al., 2018). In our study, women, community partners, and researchers work together to address the unequal distribution of social determinants (e.g., socioeconomic status, access, and gender) that contribute to health and social inequalities for women living in Kingston. ABR is a research methodology in which artistic process expressions, in all different art forms, are used as a primary source material to explore, understand, represent, and even challenge human action and experience (Segal-Engelchin et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2017). We used ABR to explore the experiences of access to healthcare and social services for women living on a low income through photovoice, with the goal of generating critical consciousness and social change. Critical consciousness focuses on a rigorous analysis of the existing reality and how it might be transformed through dialogue by participants (Camargo-Plazas & Cameron, 2015). A hermeneutic phenomenological approach helped us to examine the day-to-day experiences of participants through thoughtful questioning and interpretation of their lived experiences (Gadamer, 2006; Heidegger, 2002). Hermeneutic phenomenology is rooted in philosophical traditions as delineated by the works of Heidegger (2002), Gadamer (2006), and other philosophers. Notably, hermeneutic phenomenology is compatible with PAR and ABR as it involves a circular process where our understanding of the data was enriched from numerous readings of the study data and our interpretations (van Manen, 2016). To date, in our research, we have used this approach to garner the lived experiences and to illuminate the words of groups in vulnerable circumstances through written accounts representing their lifeworld (Camargo Plazas et al., 2012; Camargo Plazas et al., 2019; Cameron et al., 2014).

3.2 Setting and Participants

Our study is situated in the city of Kingston, Canada, where the population is 123,798 (Statistics Canada, 2017a); the prevalence of women living on a low income is 15.6% (over 19,000 individuals) (Statistics Canada, 2017b).

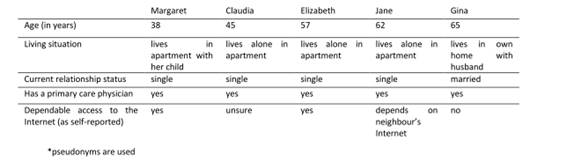

St. Vincent de Paul Society of Kingston (SVDP) is our community partner for this project. SVDP is an organization whose mission is to provide practical ‘daily living’ assistance, necessities, and support-in a compassionate and respectful manner that affirms the dignity of everyone-to individuals and families residing in the Kingston area who may be in need due to limited income [short or longer term] (SVDP, 2020). In 2019, SVDP staff served 18,378 free meals and distributed 2,559 free food pantry orders. Also, through a “Wearhouse” program, they provide individuals with free winter coats, boots, and other clothing items, as well as household items and furniture (SVDP, 2020). We used purposive sampling to engage five women from the Kingston urban area as participants (see Table 1 for participant descriptors). All individuals receive services from SVDP.

3.3 Data Collection

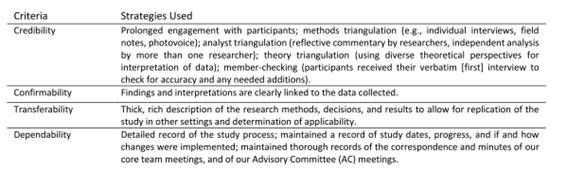

We used a combination of methods, including photovoice and semi-structured interviews, to help us describe and understand the experiences of women living on a low income as they access healthcare and social services; in this paper we focus on the interviews. Participants were asked to take photographs that represent something about their experiences. The images and their accompanying photo-text descriptions became interpretive texts (Berman et al., 2001), and were used both as prompts for the interview discussion and as a primary data source (Hansen-Ketchum & Myrick, 2008); a separate forthcoming manuscript details the complete analysis and findings regarding the photos. During two individual interviews, participants were asked about their experiences with accessing health and social services and were encouraged to explore five of their photographs. Due to COVID-19 restrictions, one participant’s initial interview was conducted via Zoom© and the remaining four were conducted by phone as some participants did not have access to Internet. The first interview typically lasted approximately one hour. A second (shorter) interview was conducted by phone with all participants to check accuracy and to clarify information. Each conversation was transcribed verbatim using Otter.ai©, and independently proofread for accuracy by two researchers. De-identified data were stored on a secure server at our university and was only accessible to research team members. Our strategies to address trustworthiness of the study are presented in Table 2. Ethics approval was obtained from university General Research Ethics Board (TRAQ# 6024959). We adhered to the ethical principles of conducting research with human beings as outlined by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, and Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (2018).

3.4 Data Analysis

In our analysis of interview data and photo-texts, we used van Manen (2014) thematic analysis and Loppie-Reading and Wein’s (2013) SDH framework. We read the transcripts as a whole, then as sections of description and stories, then as phrases and words. We developed thematic moments as we were reading the transcripts to ensure turning to the essence of lived experience. We continued with a reflection on essential themes. We followed with a process of writing and re-writing, which is an artistic activity where we went back and forth between the whole and the parts (van Manen, 2016). The iterative process of writing and re-writing increased our understanding of the world of women living on a low income, and their knowledge and experiences of access to healthcare and social services.

4.Results

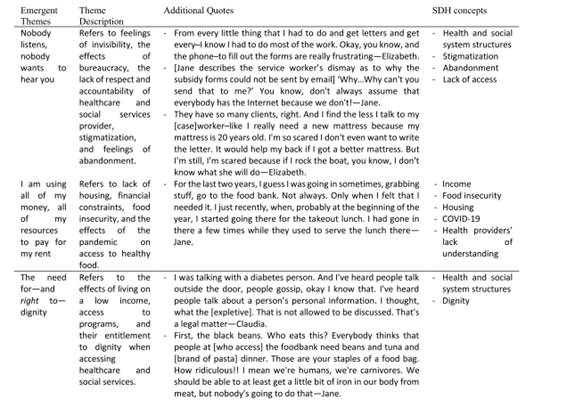

Through our analysis of interview transcripts, we identified three themes: 1) Nobody listens, nobody wants to hear you; 2) I'm using all of my money, all of my resources to pay for my rent; and 3) The need for-and right to-dignity. Table 3 is a presentation of the three themes, descriptions of each, additional quotes, and relevant SDH concepts.

4.1 Nobody listens, nobody wants to hear you

For the theme, nobody listens, nobody wants to hear you, women described being held back by bureaucracy, including feeling invisible, stigmatized, abandoned, and treated with a lack of compassion as they navigate the healthcare and or social service systems. For Elizabeth, the real problem of system access is no one takes responsibility or an interest in helping them to solve their problems; she identified: “The social workers' hands and the counselor, everybody's hands are tied because they don't have the money, they don't have places. Nobody wants to take a real interest and, kind of, trying to solve the problems.” Waitlists, lack of in-person contact with social workers, paperwork, and bureaucracies are part of the stories of the women. Elizabeth identified clinicians and caseworkers are subject to increasingly fragmented rules and regulations that impede supporting and assisting individuals when accessing social services. Similarly, Margaret explained:

I wanted behavioural-based services [for her child who has a developmental disability]. Well, [they’re] not going. [Their] name’s nowhere close to that waitlist to get those services. I have to send [$6,000] back to the [organization name] and not even be able to apply for another round of funding.

Jane echoed that paperwork and bureaucracies create barriers to accessing social services. She has endured chemotherapy treatments for her lung cancer, which has decreased her ability to focus. Coupled with limited access to her caseworker, she spends hours struggling by herself to answer the questions on the rent subsidy application. Jane explains even if she attends the social service office, she is not granted access to communicate with her caseworker; instead, she must go through the security guard to relay communication and pick-up or drop off forms. She shared:

You know there's so much paperwork. You can't go in to see them. But, geez, you know, we could talk on the phone, you know, they could do this over the phone, but they don't want to do that. They don't want to help you.

Navigating the social services system is more than challenging for the women, especially during the pandemic when in-person services were moved online, rendering them ‘invisible’ given not everyone has the privilege of internet access. However, participants do not complain. They continue to follow the rules and recommendations given by the caseworkers, yet they receive poor or no attention, and do not have trust in the caseworkers to help in meeting their needs. This mistrust causes some participants to remain quiet because they do not want to jeopardize their social assistance.

When accessing healthcare services, participants described being stigmatized and feeling desperate for someone to listen to them. Margaret shared: “Nobody listens, nobody wants to hear you.” Jane mentioned an unfavourable experience when she went to a plastic surgeon for a biopsy; she recalled:

I went to a plastic surgeon, and she has the bedside manner of a rock. She was just rude. When they took out the biopsy, I said please make sure that you put dissolvable stitches in there. You know, this thing's tender, it's sensitive. She [let] a student do it. And no dissolvable stitches. I ended up having to take them out myself.

Margaret felt when providers learn about her past of having a substance abuse disorder there is an uncompassionate tone, poor treatment, and lack of respect. She reflected: “They look at it as, oh you're a recovering drug addict. That goes up in their mind and then, you know, you get a different tone from them.” Elizabeth described an experience with a nurse who lacked compassion, stating: “I went on a diet. And I had a meeting. And this nurse, I won’t say any names, found out about my diet. She yelled at me. One of the things you don’t do to [Elizabeth] is yell...I zipped my mouth.” Jane outlined her perspective about the biggest problem with accessing healthcare and social services in her community. She detailed:

Well, you know, again the whole thing is there’s lack of empathy, lack of compassion. And of course, there’s just not enough help. It’s not enough money to live…There’s no communication with these people. None. And they don’t care. They just don’t. ‘Oh, I forgot’-though you can’t forget in this job. Our lives depend on you.

In the same breath, Jane remembered the pain she suffered when she was newly diagnosed with lung cancer. She painfully recalled feeling abandoned not only by her family, but also by social services. She eloquently expressed:

It's the sense of abandonment from the people that you trust, from the people that you thought loved you. [pause - participant crying] You thought that they cared…abandoned, again there's that word-doesn't have to just come from people that you love.

Equally, Claudia recounted feeling abandoned when asked about her support system, saying: “No, there's not enough support-I don't have enough support now. Like I have friends, okay that's fine, not a problem, but as a family-eh, not so much.” The abandonment and lack of help by care providers has pushed participants to isolate themselves from reaching out for any future help, specifically in relation to their mental health. Gina explained: “I have depression and some days I don’t want to talk or see anyone...never had counselling for my depression, I help myself.”

4.2 I'm using all of my money, all of my resources to pay for my rent

Participants discussed how a lack of services was not the main barrier to accessing healthcare and social services. Housing, accessing healthy food, or attending to other basic needs was much more important to them, and few of them sought healthcare or social assistance unless they faced severe circumstances. Elizabeth explained:

We put down $1,000 in my income a month, but it's actually $771 that I get from disability a month. It's a lot of budgeting. I have to pay house insurance. That's $34 a month because [housing company] wants you to have insurance, and then my subsidy-I have to have insurance. And that's like 100 bucks. You figure it out. [It] is money taking [taken] away from my gross.

Jane uses all her assistance funds to live with dignity-a place where she does not fear for her personal safety and well-being, and without worry of a roommate(s) stealing from her or creating an unhealthy environment. She detailed:

I'm using all of my money, all of my resources to pay for my rent because they said $1,250 is too much for a two-bedroom or for a one-bedroom. Yeah, of course, it is. But you can't find anything. What, do you think, you actually think that there are places for rent, that basic shelter [is] $497? Where the [expletive] are you going to get a place for that? But what they give me, that goes to my rent.

Participants also face money restrictions preventing them from accessing healthy food. Elizabeth articulated:

I went to the dietitian, okay, and they taught me portion size and stuff and certain foods to buy. But when you're on a low budget...Sometimes vegetables and food are too high. Like, if you go, soda pop is cheaper...treats are cheaper than real foods.

The COVID-19 pandemic has heightened problems regarding accessible food. Elizabeth stated: “Now with COVID, this winter is going to be bad for the vegetables and fruits. And some things will be out of my reach because I only have so much for groceries.” More allowance for medications, clothes, and other essential needs was also desired. Elizabeth, who needed compression socks (which the provincial Ontario Disability Support Program (ODSP) did not cover the cost of) voiced:

I wish there was more allowance for medication and for clothes. I found these socks, the compression socks. Okay, I found them for 20 bucks. You know, and I was fortunate to get them. Okay. But I think something like that should be covered.

Participants described how they must shop around for housing and other basic needs, such as buying diapers for their children or accessing healthy food. When facing financial constraints, they also access the local food bank and organizations like SVDP.

4.3 The need for-and right to-dignity

Through the very personal, honest conversations and their photographs, participants shared how living on a low income has deeply affected their lives. It has impacted them financially, emotionally, socially, and in the managing of their household or the raising of their children. Access to programs to keep themselves and their families healthy is an essential aspect of living with dignity. Elizabeth shared:

If there was a spot where we had access to fitness equipment, like yoga classes and stuff for. If it was more accessible for people, you know, especially at Christmas time or-because people are lonely. Lonely makes people sick and depressed.

Participants requested programs that help them to achieve stability in their lives. In learning about and reaching a level of understanding of how women live on a low income, we come to see the rigid structures of society. One must ‘fit’ in narrowed, administratively-determined categories or parameters, otherwise they do not qualify or benefit-a fact made worse when such programs may indeed enable healthier lifestyles. It is overwhelming to be exposed to rigid structures and rules that seemingly only threaten their health and well-being, and that are without appreciation of the complexities of human conditions and challenges. For example, Jane described: “We're on ODSP. We’re worthy. You know. We're not-like, I'm not on this to take anything from anybody. I’ve worked hard all my life. [However], you've got a [you get a] sense of pure abandonment.” They fight alone to reach a basic level of well-being and of being understood, and they have learned how to advocate for themselves. Margaret describes her lack of trust peaked when she overheard service workers talking about residents staying at the shelter where she lived; this was a turning point in speaking up for herself. She said:

There was one staff who would talk with other residents about residents and had no problems voicing it, wasn't quite right. Um, and that's when I started really sticking up for myself, like things are not okay, this is not, you know, this is not okay to do that to us.

Another important aspect of participants' stories related to wanting ‘a voice’ when accessing food services in the city. Jane rationalized the need to have some dignity when accessing foodbanks in the city, recounting:

You know the [name of agency]. You know what they have, they have a cool little system. They have, like, it's like a little grocery store, little shopping carts, and you get 30 points. And as you go through, you can see the stuff. You can grab it yourself.

For her, there is some dignity in this type of system wherein you can select what you want to eat. She also described a place where people can pay one Canadian dollar per meal. Jane said: “That's dignity. People don't necessarily always want a free hand, even though they could use it.” Jane also recalled being given expired food from the foodbank, exclaiming: “The brownies are expired [date]. Why is this supposed to be a treat for me? Am I supposed to be grateful for expired brownies because they're chocolate? That's crazy.”

5.Discussion

Although healthcare and social services is a guaranteed right for all Canadians, access barriers continue to exist which challenge this right (Lombardo et al., 2014). In our PAR, the principle of universal, positive access for everyone was contested by participants; their stories about their healthcare and social services experiences were not indicative of this value. Despite having varied life circumstances, all the participants described similar insights, barriers, and feelings of being invisible, stigmatized, and abandoned by healthcare workers and social service providers as they attempted to access and navigate healthcare and social services-services that are based on administrative regulations and rules, with little leniency for compassion. Strict healthcare and social system rules and regulations further perpetuate inequities in access for women living on a low income instead of helping. While rules and guidelines are necessary for managing resources and ensuring equal distribution of social welfare, the women’s voices speak loud and clear-excessive bureaucracy created more barriers. Chary et al. (2016) confirmed how bureaucrats in lower-level gatekeeper positions are a barrier to accessing healthcare and social services for vulnerable individuals in Guatemala. Similar results were reported by Harris et al. (2014) and Lavee (2017) who asserted poverty, negative attitudes and actions, and the hierarchical organization of the healthcare system created access barriers for individuals. Recently, however, the opposite has been demonstrated in the United Kingdom within the context of COVID-19; empowered staff have learned to prioritize care and innovate the healthcare and social systems, altering rigid rules, guidelines, and bureaucracy (Georgie & Holter, 2021).

A constant reminder by the women in our study was the pressure they felt to prioritize issues other than their own health and well-being, emphasizing the struggle of living every day in financial deprivation. Over time, ill health and social problems erupt from material scarcity (Watson et al., 2016). Participants have been forced to choose between paying for medications or food, rent, or other essential needs, resulting in unhealthy life circumstances; this makes it unreasonably difficult to protect their health and well-being. The self-determination of women living in poverty depends largely on systems and individuals in positions of power (Benbow et al., 2019). The women in our study indicated their autonomy was constricted by various external forces, which limited their capacity to meet basic essential needs, let alone consider anything they desired; it is an unsustainable situation they navigate daily. Further, those who receive ODSP or welfare payments described problems with inadequate or unstable housing and or nutrition. Lange et al. (2017), Marshall et al. (2021), and Matin et al. (2021) similarly found competing priorities, poverty, stigma, discrimination, and marginalization influence access to healthcare services for women in vulnerable circumstances. Pragmatic solutions such as having choice at food pantries, as identified in our study and that of others (Caspi at al., 2021), would be a notable improvement.

Further, our study participants found themselves having to advocate beyond what they felt they should have to, to receive the services or care they required. Each woman detailed an ability to be extremely resourceful-economically and emotionally-within a system seemingly designed to challenge their will and motivation to survive. Their resiliency and resourcefulness are evident, but the cost of which is exhausting to maintain. Women comprise the majority of “invisible” unpaid workers, taking on responsibilities such as caregiving and household work (Gladu, 2021). These “invisible” responsibilities can perpetuate physical and mental health issues (Gladu, 2021), and as demonstrated by our participants, the need to continuously advocate for oneself or others can lead to frustration and distrust in healthcare and social services. Participants voiced the need for compassion, respect, dignity, and social inclusion when accessing services. Their stories address the urgency to create strategies that alleviate the abandonment and oppression they feel every day. At a minimum, they ask for respect-being perceived as a human being-one who is inherently worthy of moral value. Respect for others requires us to appreciate human beings as deserving of attention and treatment (Dillon, 1992); the women in our study felt neglected in this regard.

Generally, the ‘sting’ of abandonment and lack of support and understanding was also felt by our study participants, as they were often not being heard, valued, or treated as a human being worthy of compassion from service providers. In Watson et al.'s (2016) qualitative study, individuals who self-reported as being homeless, revealed the people who provided them social support were friends or social service providers; some participants reported no meaningful social interaction and support from friends, families or social workers. For our study participants, their resounding collective experiences of trying to ‘fit’ into health and social systems in which there was no place for them, makes them feel uncared for and dehumanized, yet they persevere.

While this study affirms some existing evidence and deepens our understanding of hardships, priorities, and individual comforts for daily living of women on a low income, we acknowledge it has limitations. This research is being conducted at one site/setting, and as such the findings may not be transferrable. Additionally, this study was implemented during the pandemic. Due to those restrictions, we could not conduct in-person interviews which might have elicited different degrees of depth or focus during the conversations.

As we move beyond our preliminary results to completed findings from all phases (including a separate forthcoming article with a singular focus on the photo analysis), we will be sharing what we have learned and conversing with members of the city during a Knowledge Exchange event. We are hopeful of the broader impact this knowledge translation event will have, which will also include the planning of smaller scale initiatives with the partner site as proposed by participants.

6.Final Considerations

Access to healthcare and social services is a right for individuals who live in Canada. It is tragic if women living on a low income do not feel they have equal opportunities to use available healthcare and social services. Stories shared by the participants indicate how low income and gender intersect to influence women’s experiences of health and well-being, including the barriers that affect use of healthcare and social services. Participants perceived the care within the healthcare and social services system as dismissive. They felt like mere spectators, without a voice. For an individual to feel others view them as unworthy of care, especially if those ‘others’ are the care providers, is ethically and morally distressing-and it certainly does not invite system-use. Issues of access relate to healthcare and social services, as well as to adequate living conditions, housing, and affordable food. Despite these experiences, the participants continue to be resilient and hopeful. Considerable system improvements are required. Adjusting institutional structures and changing providers’ attitudes could alleviate some of the problems of accessibility. It is crucial to listen to the voices of women living on a low income, so that together, implementation of solutions for sustainable, meaningful change can occur.