1. Introduction

Kidney disease is a life-limiting illness, as well as a worldwide public health concern that affects one in 10 Canadians (Bello et al., 2019) and one in nine individuals globally (Bikbov et al., 2020). It is associated with a high physiological and psychological symptom burden and increased morbidity and mortality, and has significant implications for quality of life and personal and social costs (Davison & Moss, 2016; Davison et al., 2015). At the end of the disease spectrum, kidney failure is defined as the irreversible decline in kidney function requiring kidney replacement therapy (i.e., dialysis or kidney transplant) or conservative kidney management (i.e., active symptom management that does not include dialysis) to improve the quality or longevity of life (Davison et al., 2015; Harris et al., 2019, 2020; Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes [KDIGO], 2013). The median survival for people on maintenance dialysis is four to five years (Lam et al., 2019). This has implications for shifting the limited focus on the prolongation of life to the amelioration and improvement in quality of life through kidney supportive care.

Kidney supportive care (KSC) integrates the principles of palliative care (PC), such as symptom relief through early identification and treatment of problems, into routine care for people with kidney disease throughout the continuum of care (Davison, 2021; Davison et al., 2015; Gelfand et al., 2020; World Health Organization, 2020). It subsumes advance care planning (ACP), which involves multiple discussions between the individual, their family, and the health care staff to ensure the received care is concordant with the individual’s values, life goals, and preferences regarding future medical care (Davison et al., 2015; Diamond et al., 2020). The problem is supportive care is underused and often initiated late in the kidney disease trajectory (Sawatzky et al., 2016). The delay or lack of engagement in supportive care for people with kidney disease can lead to the underuse of such care and late referral to the specialist PC service (Noble et al., 2017), leading to unnecessary suffering by patients and their families (Davison, 2002). As such, most patients receiving dialysis die in acute care facilities while receiving high-intensity care that may be incongruent with their prior wishes, and without accessing community PC services (Davison et al., 2015; Wachterman et al., 2017; Wong et al., 2012). This has significant implications for dialysis nurses and their skills and knowledge in identifying burdensome symptoms that would warrant having ACP discussions with patients and their families about what constitutes a meaningful life or death for them.

There is, however, a paucity of research about the process of engagement in KSC as perceived by dialysis nurses-they who are “most present being the ones that are most silenced”-and the barriers that limit opportunities to meaningfully engage in such conversations during the everydayness of clinical practice (Thorne et al., 2016, p. 98), particularly within the Canadian context. As such, we undertook a study with the purpose of explaining this process of nurse engagement using Charmaz’s (2006, 2014) constructivist grounded theory method (GTM) as subjective and experiential data are essential for exploring what sustains and influences dialysis nurses regarding KSC that then renders them capable of providing it to patients. Only with this information can practice improvements be advanced, meaningful, and sustained. The overarching question of that main study is: What theory explains the process of engagement in kidney supportive care by dialysis nurses in Canada? A complete description of the study is planned for a forthcoming publication. In the present paper, we address a sub-question of the main study: What are the personal, professional, organizational, and environmental factors that shape nurses’ attitudes/beliefs toward and knowledge of kidney supportive care in dialysis?

2. Theoretical Framework: Conceptualization of Kidney Supportive Care

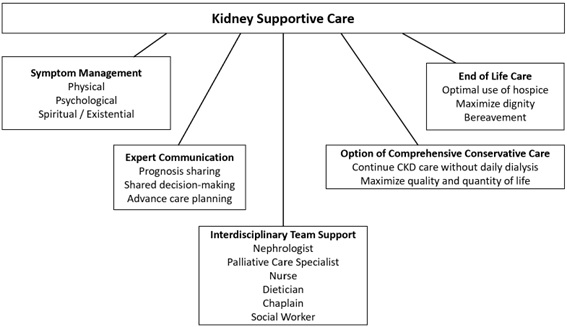

Our qualitative study has been adapted from Gelfand et al.’s (2020) conceptualization of KSC and applied within the context of the role of the dialysis nurse. The domains of KSC are illustrated in Figure 1. The focus of the study is the ACP component of the expert communication domain, to the extent dialysis nurses have conversations with their patients about ACP. It is understood the symptom management domain is within the ethical scope of nursing practice and the dialysis nurse is a key member within the interdisciplinary team support domain. The comprehensive conservative care and end of life care domains are out of scope for the study, as these are implicated outside of dialytic therapy. The contribution of the dialysis nurse with respect to cultivation of the interpersonal relationship with the patient-family unit is paramount to the success of the supportive care process in dialysis. This study is premised at this granular level of engagement by the dialysis nurse.

Note. From “Kidney Supportive Care: Core Curriculum 2020,” by S. L. Gelfand, J. S. Scherer, and H. M. Koncicki, 2020, American Journal of Kidney Disease, 75(5), p. 794. Copyright 2020 by Elsevier. Reprinted with permission.

3. Methodology of the Study

In this study, we followed Charmaz’s (2006, 2014) constructivist GTM with its symbolic interactionist (SI) heritage for its capacity to generate a theory about the phenomenon of nurse engagement in KSC with patients in Canada. The emphasis of SI on an agentic actor who interprets their situation is particularly relevant to our study because it can lead to greater insight into what is really going on in the nuanced nurse-patient relationship in dialysis in the context of everyday practice (Charmaz, 2014). It is thus important to understand what nurses know about their situatedness and believe to be important (Benzies & Allen, 2001). Thus, social reality is multiple and processual, making the interaction between researcher and participant co-constructed (Charmaz, 2014). Data then are constructed rather than discovered and the constructed analyses are merely interpretive renderings, rather than objective reports of the empirical phenomenon under study (Charmaz, 2009, 2014).

3.1 Setting and Participants

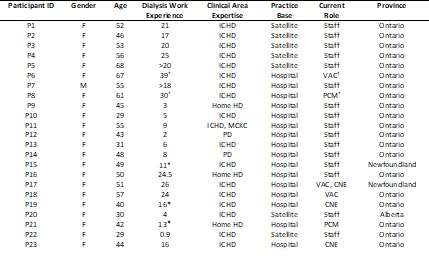

Twenty-three dialysis nurse participants (hereafter denoted as “P”) were recruited. Purposive sampling was initially used to recruit nurses working in in-centre hemodialysis (ICHD) centres (i.e., based in hospital and/or within a satellite centre). For refinement of the categories in the emerging theory, a theoretical sample of nurses working with patients receiving home-based peritoneal dialysis and hemodialysis across three Canadian provinces was used (Charmaz, 2014). Apart from offering training support, home-based dialysis nurses largely provide remote telephone support when medical or technical issues arise for patients who dialyze independently at home. In contrast, in-centre hemodialysis nurses provide direct care to patients who dialyze at hospital or satellite centres. The nurse-patient interface varies between the different modalities. Interviews were conducted predominantly via Zoom© teleconferencing platform, and some by telephone. Participant characteristics are described in Table 1.

†Retired; (Has left nephrology; (Including international experience

Abbreviations: CNE=clinical nurse educator; F=female; HD=hemodialysis; ICHD=in-centre hemodialysis; M=male; MCKC=multi-care kidney clinic; PCM=patient care manager; PD=peritoneal dialysis; VAC=vascular access coordinator

3.2 Data Collection

The method of data collection comprised semi-structured interviews. In GTM, the researcher starts with the participant’s story and expands on it by locating it within a basic social process that is responsive to the fundamental opening questioning of: “What is happening here?” (Charmaz, 2014, p. 87). Twenty-two participants completed two semi-structured intensive interviews each, and one participant cancelled the second interview. On average, the first interview lasted 50 minutes and the second lasted 26. The two interviews were conducted approximately three months apart to accommodate the in-depth transcription process while navigating the challenges of recruiting dialysis nurses during the pandemic. Each interview was audio- and video-recorded via Zoom© videoconferencing platform and transcribed using Otter.ai©. Transcribed data were input into NVivo© (QSR International). The transcriptions were verified for accuracy by the principal investigator (first author) and last author. De-identified data were stored in an encrypted external hard drive on our university’s servers. Access to data was limited to the first and last authors. The strategies used to ensure trustworthiness, as outlined by Charmaz (2006, 2014), are listed in Table 2. Ethics approval (TRAQ# 6035254) was granted by our university Health Sciences & Affiliated Teaching Hospitals Research Ethics Board.

Table 2 Trustworthiness of the Study (Based on Charmaz, 2006, 2014)

| Criteria | Strategies |

|---|---|

| Credibility | Use of verbatim transcription and in-vivo codes Triangulation of methods: interviews, observation, field notes, research journal, memo-writing Member-checking (participants were given the opportunity to read the transcripts for accuracy) Principal investigator’s clinical expertise in and knowledge of the substantive area under study, philosophical congruence with constructivist GTM, and rigorous approach to data collection and analysis (i.e., concurrent data collection and analysis, constant comparison) Strong reflexivity |

| Originality | New insights gleaned from preliminary study findings Study represents fresh conceptual rendering of the data Well-established, multi-dimensional significance of study |

| Resonance | Interview questions reframed when new insights and perspectives gleaned from hearing participants’ stories Member-checking to ensure accuracy of transcripts Participants given opportunity to ask researcher questions at the end of the interview |

| Usefulness | Member-checking to ensure transcripts reflect accurate interpretations of participants’ narratives of their everyday practice Preliminary findings suggest multi-dimensional significance in practice, education, research, and policy domains within kidney care |

3.3 Data Analysis

GTM is an emergent process for yielding a theory that is generated and integrated through rigorous application of the essential GTM steps (Birks & Mills, 2011). This process includes key analytical and reflexive strategies, such as constant comparative method and memo-writing, which are done concurrently with data collection and aid in the process of theory building (Tweed & Charmaz, 2011). The process of transcribing interviews is part of coding, by listening to recordings before transcribing and by reading/re-reading the interview text (Tarozzi, 2020). Charmaz (2006, 2014) describes initial or open coding followed by focused coding and then by theoretical coding. In initial coding, line-by-line coding was undertaken by selecting segments of text (constituted by sentences, phrases, or whole paragraphs) that were deemed meaningful to the research question (Tarozzi, 2020). Coding with gerunds and in vivo coding were undertaken to adhere to the participants’ words (Tarozzi, 2020). Using gerunds allows the researcher to focus more on the actions and processes within the data and less on the researcher’s interpretation of these events (Hadley, 2017). In vivo coding allows for a deeper understanding of the meaning of the participants’ words and their emergent actions (Charmaz, 2014, 2015). Focused coding is the second major stage of data analysis that builds on and moves beyond open coding (Birks & Mills, 2011). Initial codes that were deemed to be related were grouped together as categories (Hadley, 2017), and relationships and patterns between categories were identified (Birks & Mills, 2011; Charmaz, 2015). This phase is where the core analytic and reflexive strategies of concurrent data collection and analysis, constant comparison of data against data, memo-writing, theoretical sampling and saturation, and theoretical sensitivity occurred (Tie et al., 2019). It is anticipated we will attain the last phase of coding, theoretical coding, by creating theoretical connections between categories and the central core category to create a substantive grounded theory (Charmaz, 2014; Mills et al., 2006; Tie et al., 2019).

4. Results

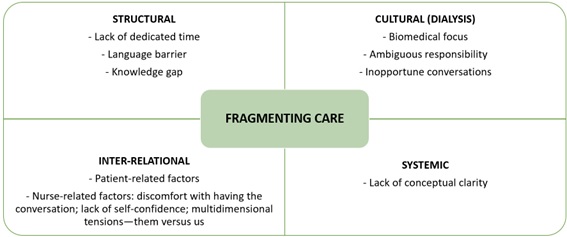

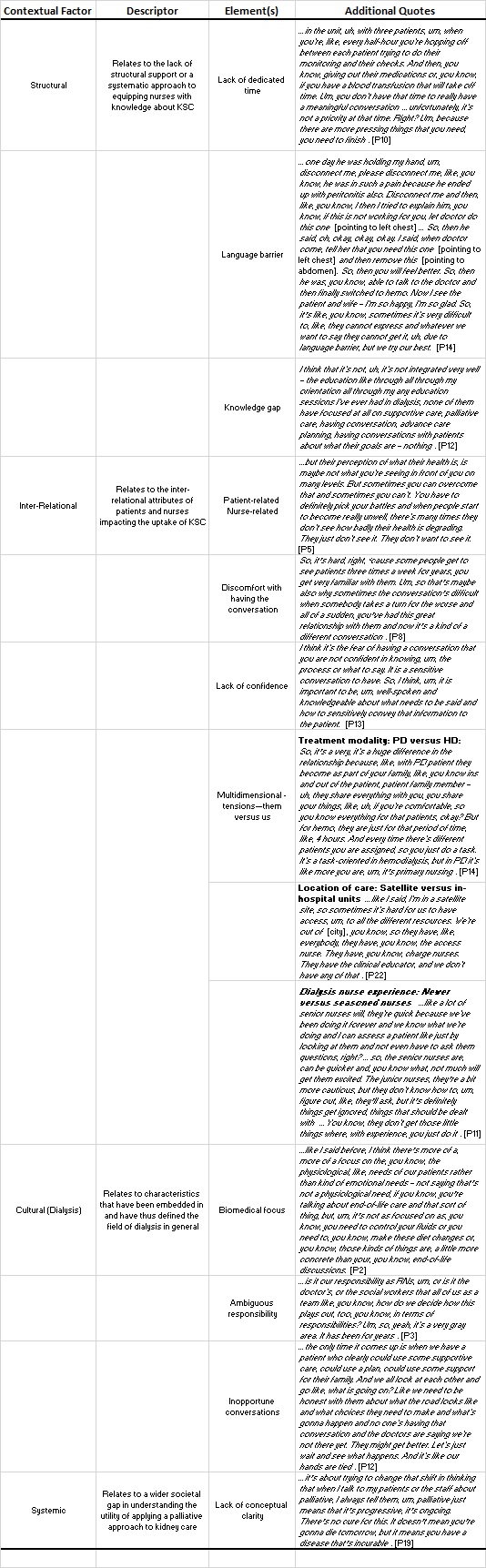

Through constant comparative analysis of the interview data, the core category of Fragmenting Care is explained by four categories of contextual factors and their related concepts and sub-concepts: (1) structural (lack of dedicated time, language barrier, knowledge gap); (2) inter-relational (patient-related factors, nurse-related factors [discomfort with having the conversation, lack of self-confidence, multidimensional tensions]); (3) cultural-dialysis (biomedical focus, ambiguous responsibility, inopportune conversations); and (4) systemic (lack of conceptual clarity).

Figure 2 illustrates the confluence of these factors into the core category. Additional quotes supporting these factors are listed in Table 3.

4.1 Structural Contextual Factors

The following structural contextual factors were identified by three concepts: lack of time, language barrier, and knowledge gap.

Lack of Dedicated Time

Several participants working in HD noted lack of time due to busy workloads or competing priorities in the dialysis unit prevented them from conducting meaningful conversations with patients about their understanding of their illness and goals of care. P3 stated that “when you engage in that kind of conversation and you’ve got multiple people on machines that you have to care for, you can’t always get into a deep discussion.” P3 recalled how the unit charge nurse “went around and did this quick sort of person-to-person and try to get an idea of where [the patients] were in terms of their planning.” In this context, being rushed is just as ineffective as not having the time for such meaningful conversations about what matters most to patients.

Language Barrier

Language barriers were also noted to be prohibitive in providing KSC to patients. P7 stated patients “don’t have no clue what’s happening with them” due to the “lack of language.” P9 alluded to the challenges faced by those for whom English is not their first language. It is noteworthy that both participants are immigrants to Canada, which lends credence to the issue of language barriers in the care setting. Providing KSC without acknowledging the prohibitive nature of the language barrier places the patient’s voice at risk of not being heard, which has significant implications for their care.

Knowledge Gap

Finally, many participants noted a knowledge gap about KSC, particularly in engaging in conversations with patients. In general, participants appealed for more knowledge. For example, P12 stated her passion for HD made her “want to continue to gain more knowledge.” P1 noted “getting some education and courses behind you” makes having such conversations “more smooth and…you can be a better care provider that way.” However, P22 stated “there’s been no…webinars or any education…there’s been no resources, there’s been nothing sent to us.” Interestingly, certain participants stated they sought their own learning. For example, P14 stated that “formal, continuous education” is lacking and that it is “basically self-learning most of the time.” P16 found online searching for “palliative stuff” to be effective.

Regardless, this current knowledge gap is consequential in that nurses, as P3 testified, “don’t know how to approach the conversation” nor “start the discussion.”

4.2 Inter-Relational Contextual Factors

The following relational factors were identified by the following concepts and sub-concepts: patient-related and nurse-related (discomfort with the conversation, lack of self-confidence, and multidimensional tensions) factors.

Patient-Related Factors

Patients have been described as possessing attributes or ways of being that contradict the narrative that kidney disease is a progressive and life-limiting condition. P5 aptly noted patients “just don’t see…or don’t want to see” their own deterioration. P2 concurred they “have very little insight” into their illness. P15 remarked patients have unrealistic expectations, such that “they think they’re doing better than what they probably are, physically.” As a result, they think “they’re going to live forever and they don’t want to have that discussion” (P3), when, in fact, they “don’t realize that they’re dying” (P11). Further, patients do not see dialysis as a “palliative treatment until they are literally so unwell” (P5). The total effect of these attributes impacts how nurses engage in KSC, insofar as to whether patients allow themselves to be open to the possibility of envisioning what they desire now for their future care.

Nurse-Related Factors

Dialysis nurses face a myriad of complex barriers relating to their experience and practice.

Discomfort with Having the Conversation

This finding suggests dialysis nurses are not always comfortable with discussing the “elephant in the room,” which P19 described as “talking about…offering palliative supportive care to patients,” such that it is not discussed. P2 noted having an end-of-life care conversation is made more difficult because it is a “really tough conversation to have” because “it’s an emotional thing.” P8 stated familiarity with patients makes the conversation difficult, particularly when the patient deteriorates. Additionally, P5 noted nurses are afraid of “talk[ing] about dying.” Failure to address the “elephant in the room” because of the nurses’ lack of comfort with having the conversation about goals of care or end-of-life care becomes prohibitive in delivering KSC, which has implications for strategies to mitigate this discomfort, such as education and training. As P17 said, “[nurses] just need to be more comfortable with having the conversation.”

Lack of Self-Confidence

Related to the discomfort with having the conversation, some participants expressed a lack of self-confidence in conducting it. This includes not “knowing the process or what to say” (P13) or feeling “a little out of the water with some of these conversations” (P16). As P14 succinctly expressed, “if you are not comfortable or you are lacking knowledge, you will just superficially do the task, but it won’t help the patient because you are not yourself confident in that.” Thus, lack of self-confidence, within the context of having a knowledge gap about KSC, further compounds the discomfort with having important conversations.

Multi-Dimensional Tensions

Participants described multi-dimensional tensions created by the perceived differences in impact on nursing practice. The differences between dialysis modality, location of care, and dialysis staff work experience reflect distinct levels of tension.

Dialysis Modality: HD and PD

The home dialysis participants alluded to having closer relationships with their patients. P14 stated PD patients are considered “part of your family.” P21 noted home HD nurses spend an inordinate amount of time on one-on-one training with patients. However, P13 stated in-centre HD affords a closer relationship with patients because “in hemodialysis, you are in the department. The patients are in front of you. You are accessible to them and you’re having more conversation.” Additionally, P8 stated, “PD is very much you’re teaching” patients to be independent, “whereas in hemo, you do [dialysis] for them.” P19 reflected on how HD becomes the default for patients having PD failure, and it is in HD “where you see more of the end of life.” These differing perspectives have important implications for educating the dialysis nurse on the nuanced differences in approaching KSC in either HD or PD.

Location of Care: Satellite and Hospital-Based Dialysis Units

Participants described differences between satellite and in-centre dialysis settings related to available resources and accountability for care. P22 lamented that being in a satellite, “it’s hard for us to have access to all the different resources” that hospital units have. P16 noted “when things happen, when things go down…you know, when you’re at the satellite, you are the person and there is no passing off.” Nurses, thus, become “trouble-shooters” (P20) and “ringleaders” (P1). These experiences situate the satellite nurse as having to do more with less resources, which has implications for the nurse’s capability to deliver KSC.

Staff Experience: Newer and Experienced Nurses

Observations from seasoned and newer nurses provide a glimpse of how nurses negotiate tensions surrounding staff experience in practice. P11 stated “senior” nurses are quicker because “we’ve been doing it forever.” P10 alluded to the difficulty of having conversations about KSC with patients as a newer nurse; however, experience affords comfort in having a more personalized conversation. The experiences of both newer and seasoned dialysis nurses have implications for mentorship of the former by the latter.

The sum of these inter-relational tensions reflects a “them versus us” approach in practice that dialysis nurses face daily, underscoring the challenge of prioritizing meaningful conversations with patients about their values and preferences for care.

4.3 Cultural (Dialysis) Contextual Factors

The following dialysis culture-related factors were identified: biomedical focus, ambiguous responsibility, and inopportune conversations.

Biomedical Focus

The dialysis work environment is perceived as task-oriented and automated. It has been likened to “Amazon nursing” that prioritizes electronically documenting on a retail checklist of nursing care tasks (P16). Dialysis is seen as a “kind of conveyor belt treatment” (P6). The focus is more on the patient’s physiological needs than on matters such as end-of-life discussions (P2). Despite this characterization, P16 has taken the following stance: “I know I’ll be able to always document but that my concern has always been to give an opportunity to the patient, to open up about how they’re really doing.”

Ambiguous Responsibility

Nurses are seen as shouldering many responsibilities. P3 elaborated nurses have been encouraged to discuss ACP with patients, but “we [nurses] always felt it should be something that the doctor should be doing.” This same deflection can be seen with nephrologists. In situations warranting convening family meetings to aid in determining patients’ goals of care, P12 stated the “[nephrologists] will say, well, the social worker can deal with that or, you know, the hospitalist, that’s their issue.”

This grey zone, where clinicians stay within their “realm of responsibility” (P6), can derail the implementation of KSC in the dialysis setting.

Inopportune Conversations

Conversations about KSC, such as goals of care, are not “very present” in the dialysis unit (P3). Such conversations are not “discussed outwardly in [the] unit” (P15). P12 exclaimed that “nobody talks about it.” However, when the conversation does occur, it occurs too late in the disease trajectory. P12 stated nephrologists “…will bring palliative care in at the last second as the patient is imminently dying and is suffering horribly and families - they’re screeching for something to happen, and they are at a loss, and they call in palliative care.” Having the conversation late in one’s care process can have devastating repercussions.

4.4 Systemic Contextual Factor

The following systemic factor was identified with the concept of lack of conceptual clarity.

Lack of Conceptual Clarity

Most of the participants had difficulty articulating the concept of KSC. P14 couched her definition in terms of preventative care. P23 interpreted the concept within the context of meeting the biomedical needs of the patient. In addition, PC is associated with “cancer and terminal and dying” (P19). Disturbingly, participants believed patients equate stopping dialysis with suicide (P1, P5, and P19). The implication for action aligned with these misperceptions lies in shifting the way palliative or supportive care is perceived. Indeed, this needs to start from multiple arenas, from the bedside to education and, ultimately, to public opinion. In turn, this has significance for emboldening nurses with knowledge about KSC to ensure its informed implementation.

4.5 Fragmenting Care

The sum of these contextual factors ultimately leads to the core category of Fragmenting Care, in which the delivery of care is compartmentalized. This is illustrated in the deflection of responsibilities related to the discussion about goals of care and ACP to other members of the kidney care team. Nurses appear to be engaging in an unstructured delivery of KSC, but the preliminary findings are an indictment against the current system of care that does not prioritize mitigation of these contextual factors. This has important implications for our study in helping to reconcile these factors in a theory that explores the phenomenon of engagement by dialysis nurses in KSC.

5. Discussion

The preceding discussion centred on the preliminary findings of the contextual factors that shape the engagement by dialysis nurses in KSC. Collectively, these findings are consistent with the literature. Several researchers have found the lack of dedicated time to engage meaningfully in conversations with patients about matters, such as goals of care, led to nurses feeling disempowered and unable to conduct such conversations (Berzoff et al., 2008; Sellars et al., 2017; Smith & Wise, 2017). This finding strongly resonated in our study, which lends credence to ACP as not being a priority (Hutchison et al., 2017). Similarly, the knowledge gap about elements of KSC was corroborated by the results of Axelsson et al. (2019, 2020) and de Barbieri et al. (2011). However, the finding regarding language barriers in the clinical setting appears to be unique to our study.

Our participants believed patients receiving dialysis essentially do not appreciate the life-limiting nature of their illness; as such, they do not want to talk about ACP pertaining to their health. As in Hutchison et al.’s (2017) results, there is a perception such discussions occur only when one is dying. Similarly, nurses’ discomfort with having the conversation about supportive care was consistent with Haras et al.’s (2015) finding that the perception of comfort is the strongest domain associated with nephrology nurses’ perceptions toward ACP. However, we surmise additional education and training would mitigate this barrier. In Sellars et al.’s (2017) study, incorporating ACP into routine practice aided in helping the nephrology nurse participants feel more comfortable with discussing death.

The finding about the multidimensional tensions nurses negotiate daily in their practice appears to be emergent and unique to our study as well. The juxtaposition of promoting independence in patients through home dialysis therapies and the fostering of dependence of patients on nurses in outpatient HD has been revelatory. This becomes more interesting in the backdrop of some participants with experience in both PD and HD, touting the greater connectedness with their ‘independent’ patients living at home than in outpatient HD, where there is greater physical nurse-patient interface. Despite this, there is a perception in the literature that the biomechanical approach to patient care in dialysis settings is dehumanizing (Aasen et al., 2012; Smith & Wise, 2017). Some participants clearly attested to this belief. The ambiguity in responsibility for ensuring the implementation of KSC in our study correlates well with O’Hare et al.’s (2016) finding about the poor demarcation of the roles and responsibilities regarding ACP within a team setting in dialysis.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, our study showed the conversation about supportive care in clinical practice is not happening and, when it does, it occurs when the patient is imminently dying. This supports Lazenby et al.’s (2016) finding that nephrology physicians and nurses hold such discussions only when patients start deteriorating. Hutchison et al. (2017) and Feldman et al. (2013) similarly found ACP becomes most relevant at the end of life. Such misperception of KSC leads to a shared misunderstanding and eventual lack of conceptual clarity that permeates many levels of care. The collective impact of the contextual factors in our study ultimately leads to fragmentation in the delivery of KSC, which is consistent with the overarching theme of complex and fragmented medical care in O’Hare et al.’s (2016) study. There are multiple implications in the practice, education, research, and policy domains for mitigating these contextual barriers at the bedside and beyond, mainly because these contextual factors are interwoven in such a way that it may be difficult to isolate one from the others. Such is the current state of dialysis nursing practice.

Our study provides a unique perspective in that it is solely about nurses by nurses for nurses within the Canadian context. Our preliminary results about contextual factors shaping nurse engagement in KSC affirm much of what is in the literature, but we offer fresh insights into the nuanced nurse-patient interface in dialysis, for which the conclusion of our constructivist GTM study should render the final representation of this phenomenon as trustworthy.

5.1 Strengths and Limitations

To our knowledge, our main study is the first to focus solely on dialysis nurses’ experience of engagement in KSC within a Canadian context. Regarding the sub-question reported herein, the finding of multi-dimensional tensions in the workplace is a novel contribution to the body of literature addressing the underuse of ACP-related conversations in the clinical setting from the provider perspective.

In conducting the main study, we encountered limitations and challenges. COVID-19 pandemic restrictions contributed to recruitment difficulties. As such, interviews were conducted mostly online via Zoom©. The Zoom© platform was a good surrogate for in-person interviews, but it could not supplant direct observation and contact with participants that might have allowed for a richer and more nuanced research-participant interaction. Additionally, the ‘insider’ status of the first author as a former dialysis nurse had potential implications for maintaining a balance of simultaneously being faithful and true to the participants’ experiences and being open-minded about the researcher’s subjectivities about the topic. Finally, the first author is a novice researcher with prior limited exposure to GTM and its iterative and comparative research strategies, which might have led to unfocused categories or premature closure of analytic categories (Charmaz, 2015). Strong reflexivity and team discussions were key in mitigating these limitations.

6. Conclusion

In this paper, we have focused only on the contextual factors that are part of an emergent theory about Canadian dialysis nurses’ engagement in KSC. These multi-level influences span the structural, inter-relational, cultural (dialysis), and systemic realms. Left unchecked, these factors contribute to the fragmentation of dialysis care. As such, they impact how KSC is implemented for the vulnerable population of individuals suffering from the chronic and life-limiting condition of kidney failure when treatment itself becomes burdensome to the point when discontinuing it should be presented as a viable and compassionate option. Dialysis nurses have a crucial role in the implementation of KSC. The nurse-patient interface at the bedside is a sacred space, at which significant sayable and unsayable communication takes place. It behooves nurses, then, to use this space to have the conversation with the patient receiving dialysis about the care implications of having such a life-limiting illness. This nurse-patient interface becomes a starting point for the delivery of comprehensive and holistic dialysis care. Primacy should then be accorded to constructing a theory that further delineates nurses’ engagement in KSC in Canadian dialysis settings that would mitigate the impact of the contextual factors in this article on dialysis nursing practice.