1.Introduction

Tenure-track process, an educator’s journey to academic job security and promotion, can be an extremely competitive experience (Bice et al., 2019). Developing scholarly research and creative activity (SRC) partnerships with senior, tenured faculty within academic institutions is considered the ideal approach to cultivating a strong program of research (Busby et al., 2022; Lee at al., 2017). Particularly, when there is an option to pair novice faculty with a midcareer or a late career scholar, the midcareer scholar is better suited at providing support on the tenure process while the late career scholar is better suited at providing SRC support (Webber et al., 2020). While these partnerships are mutually beneficial, they provide novice faculty with an opportunity to receive mentorship (Busby et al., 2022), coaching (Ragins & Kram, 2007), role modelling and counselling (Busby et al., 2022; Ragins & Kram, 2007), knowledge of institution SRC processes, invitations to join research teams and guidance on grant applications (van der Weijden et al., 2015). According to Lattuca and Craemer (2015), collaboration is a broad range of activities and a social inquiry practice that promotes learning. A case study by Shieh and Cullen (2019) on the Clinical Track Faculty Mentoring Initiative provides empirical evidence supporting the effectiveness of structured mentoring programs. In the study, clinical assistant professors showed improvements in understanding promotion processes and mentorship quality, alongside increases in scholarly publications (Shieh & Cullen, 2019). There is extensive literature available on the benefits of such collaborations (Busby et al., 2022; Nick et al., 2012; Mijares et al., 2013; Shieh & Cullen, 2019; Smith at al., 2020), but literature is lacking on SRC partnerships and collaboration among novice faculty members.

2. Purpose and Research Question

Collaborative partnerships among novice faculty offer an opportunity for shared learning and professional growth. This is because they are going through the journey at the same time, doing the ‘learning’ together, experiencing the emotions, and building a collaborative toolbox of mutually beneficial skills in SRC. The purpose of this study was to examine how three novice tenure-track nursing faculty members establish and develop their research programs, and the connections between such programs for current and future collaborations, advancement of the nursing profession and scholarship, and personal-professional growth. This research question guided this exploration: What are the common narrative threads among novice nursing faculty members' stories of their evolving programs of research?

3. Theoretical Framework

This study is grounded in Creamer’s (2003) interpretive process theory, which provides a strong framework for analyzing collaborative and self-reflective narratives within academic settings. Creamer (2003) identifies four key stages that facilitate engagement among participants. These stages include: (a) dialogue, (b) familiarity, (c) collaborative consciousness, and (d) examining differences (Creamer, 2003).

The framework’s emphasis on dialogue aligns with the need for open communication in collaborative academic research. Familiarity enhances the participant’s ability to identify common themes by fostering a deeper understanding of each participant’s journey to their program of research. Collaborative consciousness and examining differences are critical for developing a shared understanding of the diverse approaches to nursing research, necessary for innovation and academic growth. Creamer (2003)’s interpretive process theory guided the study’s methodology and informed the interpretation of study findings.

4.Methodology

The qualitative methodology of Narrative Inquiry (Clandinin & Connelly, 2000) with a focus on self-study was utilized. Narrative Inquiry was selected due to the paucity of research available in this area, as well as its’ unique capacity to highlight the nuanced experiences of participants. Starting with a methodology that allows for participant voices to be amplified leads to the provision of a deeper understanding of participants' experiences and implications for future research with an increasing number of participants (Clandinin & Connelly, 2000). This methodology also enables the exploration of how these voices evolve in response to collaborative work and experiences, offering valuable insights into the processes that underpin collaboration and personal growth. This study received institutional research ethics board approval (REB: 2022 - 384).

4.1 Sampling and Recruitment

Purposive sampling, best suited for a Narrative Inquiry (Creswell & Poth 2017), was used where the study’s Principal Investigator (PI) recruited participants who were new faculty members at their school of nursing as there was interest between them to develop joint research projects to collectively advance their individual programs of research. Participants were approached through e-mail and face-to-face interactions. Creswell and Poth (2017) recommend as little as two participants for a Narrative Inquiry study. Thus, having three participants was appropriate as the study aim was to develop a collective story on the phenomenon of interest.

Potential study participants needed to: 1.) read and understand English for the purpose of giving consent for participation; 2.) self-identify as a novice tenure-track faculty member; and 3.) have an evolving program of research with, at minimum, a study completed as part of their doctoral dissertation. Thus, the study participants included three tenure-track Assistant Professors who hold a Doctor of Philosophy in Nursing and who are also the three study investigators. A relationship between all three faculty members was established prior to study commencement. The participants identified as female and were all aware of each others’ personal goals and reasons for doing the research. There were no participants who refused to participate or dropped out of the study.

4.2 Data Collection

The study took place in one of the largest nursing schools in Canada, located in an urban city in Ontario. The participants and researchers, including one research assistant, were present during data collection. Each participant was asked to undergo a self-reflection process on their lived experience of developing and executing their research programs as directed by a question guide. The question guide was created to ensure consistency across reflections, centering on key themes such as previous research experience, current research projects and future work. The question guide was not pilot tested. This occurred over a one-month period where each participant produced a narrative story of their own research program that included their SRC philosophies. Participants were also asked to document their responses using creative means (i.e., through poetry, drawing, painting, college, to name a few). All of these are aspects of the Narrative Reflective Process (Schwind, 2014) which finds its theoretical underpinnings in Narrative Inquiry and stipulates that individuals know more than they can say verbally. Upon this phase, a series of joint meetings occurred approximately one month after where dialogue ensued on the reflections to capture the intersections among participants’ research programs to explore their social significance (Schwind & Kwok, 2021). This process allowed for knowledge co-construction to occur, moving participants’ reflections from an individual activity to one that can have social significance for others experiencing a similar challenge (Clandinin & Connelly, 2000). There were no repeat interviews carried out, and the research did not use audio or visual recording to collect the data. Field notes were made after the data collection. Data saturation was not discussed. All three participants and the research assistant had access to the shared drive containing the transcripts and reflections.

4.3 Data Analysis

Creamer’s (2003) interpretive process was used as a theoretical lens. By using Creamer’s (2003) process to synthesize the self-reflections, the stages of the group’s progress were intertwined, and intersections of their research programs explored.

Various methods for identifying underlying narrative threads were adopted including thematic analysis, content analysis and constant comparative methods. Each member independently coded and analyzed the entire set of narratives, sharing these analyses with the group for review. This process served two purposes: (a) to critically understand individual perspectives and learn from each member as a focal point of their collaborative endeavor; and (b) to utilize multiple and diverse interpretations as analysis frames for understanding experiences. Their dialogue unfolded over several meetings, communications through a shared Google drive document and e-mail, refining and drafting the narrative threads through follow-up emails, highlighting the vital role of an open, non-hierarchical dialogue in their collaborative process. This process took a total of two months to unfold and involved biweekly meetings and weekly follow-up emails.

5. Findings

There was consistency between the data presented and the findings. Each participant used a metaphor to represent their research program, but the three metaphors can all be found on a walk through a ravine. Thus, connecting the three participants metaphorically when they walk through this tenure-track journey together over a bridge (Dr. Roy) with a river (Dr. Aha) flowing underneath and a tree at the end of bridge with mycelium root network growing underground (Dr. Kam). In addition, there are three common narrative threads that emerged from their reflections: (a) stakeholder collaboration and involvement; (b) nursing policy, practice, and research leadership; and (c) structures and facilitators for collaboration and constructive epistemological ontology. These threads can be identified in the members’ past and present experiences and can also provide insight into future collaborations. Only written reflections were produced and analyzed in this study, using a structured approach based on the theoretical lens provided by Creamer’s (2003) interpretive process. The participants had a range of ages, clinical and academic experiences, and tenure track advancement, with one participant in year three and the other two participants in year two of the tenure track process. Every faculty member maintained a healthy publication record as a first author for an early career researcher. All three participants selected to use a metaphor as part of their creative reflection using the Narrative Reflective Process.

5.1 Narrative #1: Tenure-Track Dr. [Concealed for review - pseudonym Dr. Kam)

Dr. Kam is a tenure-track faculty member with experience in teaching at several academic and healthcare institutions. Dr. Kam continues to maintain her nursing practice in general internal medicine. She uses the metaphor of a mycelium root to depict her program of research. The mycelium root is a myriad of delicate, branching threads that pass through soil, continuing to divide. As she shared,

Each topic that I investigate I will continue to evolve through further inquiry and/or knowledge translation with applicable communities. Thus, the threads of each topic will continue to grow and branch off into further sub-topics and subject areas.

Mycelium root differs from plant roots due to its interconnectedness - the threads have the ability to fuse together, creating an anastomosing network (Fortey, 2021). This is analogous to Dr. Kam’s use of past experiences to guide her future research. The physically separated yet interconnected roots of the mycelium branch that depict Dr. Kam’s program of research, branch out into three key topics: 1.) nursing and health professions education; 2.) nursing and interprofessional practice; and 3.) person and family-focused care and patients with social, economic, and chronic health challenges. Dr. Kam engages in research that contributes to, and enriches, the educational experiences of nursing students, nurses, and the nursing profession as a whole. By regularly conducting needs assessment in the role of a faculty member and course lead, Dr. Kam identifies gaps in nursing education and curricula.

The development of educational tools and resources has allowed her research to enhance the educational experience of nursing students, but also produce an impact on nursing practice. When describing a novel national study exploring nursing students’ educational needs in relation to medical and recreational cannabis, Dr. Kam shared,

The findings from this study will inform the development of a course on medical and recreational cannabis for a national cohort of learners enhancing nursing student and professional education in this topic area. This will in turn impact on nursing practice.

Dr. Kam’s commitment to nursing and health professions education is also evident through her involvement in the development of an International Nursing Knowledge Network, which pushes the boundaries of nursing research and education beyond local institutional and physical boundaries to have global implications. As she shared,

This project revolves around the creation of an international Nursing Knowledge Network which will focus on sharing, contribution to, and development of all kinds of nursing knowledge. Prior to this occurring, we conducted an environmental scan of resources for its creation. A total of 42 universities across the world participated in the environmental scan.

To continue, Dr. Kam aims to focus her research not only on emergent needs related to nursing practice (e.g. patient roles within interprofessional teams), but also interprofessional practice as nurses are integral members of collaborative teams. Dr. Kam frequently identifies gaps in interprofessional care and utilizes her research to address these gaps. Further, Dr. Kam frequently utilizes clinical experience to identify gaps and inform her teaching and research and share the findings of her research work with her intra- and inter-professional colleagues.

The final component of Dr. Kam’s program of research focuses on the delivery of person and family-focused care and patients with economic, social, and chronic health challenges. Dr. Kam has conducted research with individuals experiencing social isolation, homelessness and substance use as well as various chronic health conditions such as diabetes, tachycardia, breathing-related challenges, to name a few. Through her research, Dr. Kam also developed a conceptual framework on patient roles on teams in primary care to support patient participation in their own care in a way that is most meaningful for patients. As mentioned previously, while the roots of Dr. Kam’s program of research are physically separate, they are highly interconnected and dependent on each other. While above ground, the image of what will grow from this mycelium root is not yet present, akin to Dr. Kam’s program of research being in its infancy and in a state of evolution.

5.2 Narrative #2 Tenure-Track Dr. [concealed for review - pseudonym Dr. Aha]

Dr. Aha is a tenure-track faculty member with extensive experiences in clinical and educational settings as well as research sectors in Canada, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and Jordan. Dr. Aha uses a river to depict her program of research. This metaphor represents her research interest centered on women’s health, migration, social justice, and equity.

A river is a large and natural stream of flowing water. Dr. Aha uses this imagery to symbolize the flow of life experiences, challenges, hardships, and opportunities faced by marginalized women and individuals experiencing food insecurity and homelessness. Like the bifurcation and convergence of a river, Dr. Aha’s program of research branches out into two key topics: 1.) women’s health, migration, and displacement; and 2.) social justice. As she shares, “Just as a river connects diverse landscapes and ecosystems, my research explores the intersection of women’s health, migration and displacement and social justice.” Every river has been shaped by geological events and its’ present state can be understood by examining its’ past. The characteristics of a river are in close and mutual interdependence with the land which it passes through.

Similarly, Dr. Aha has developed a deep understanding of socio-cultural patterns that have contributed to the challenges and enablers for refugee women’s health, through a critical ethnographic approach. By merging critical ethnography with intersectionality, Dr. Aha explored the experiences of inequality and marginalization. Her research dives into the various obstacles faced by refugee women when accessing health services, allowing for a better understanding of the impact of migration and trauma, gender dynamics and interactions within the healthcare system. As Dr. Aha stated in her self-reflection, Always consider gender inequalities in the allocation of resources, such as income, education, healthcare, and nutrition (i.e., food and housing insecurity). I advocate for a multisectoral approach to integrating the contribution of non-health sectors including industry partners to the overall health and wellbeing of women as I strongly believe underrepresentation creates a culture that perpetuates inequalities. In her metaphor, the river’s currents represent the multifaceted aspects of women’s experiences, including their physical and mental well-being, their journeys of migration, displacement, acculturation, and the socio-political factors influencing their lives. Through the combination of critical ethnography and intersectionality, Dr. Aha explored the health needs of refugee women and identified how a blended approach can be used to inform refugee women and nursing research. The water in a river is in motion, unidirectional and can be of great force. River water continuously passes through the earth’s crust, creating profoundly different conditions for life and serving as communication channels for organisms which migrate and colonize. In her research program, Dr. Aha uses the metaphor of the river and flow of water in a river to highlight the significance of empowerment. As she shares,

Always consider gender inequalities in the allocation of resources, such as income, education, healthcare, and nutrition (i.e., food and housing insecurity). I advocate for a multisectoral approach to integrating the contribution of non-health sectors including industry partners to the overall health and wellbeing of women as I strongly believe underrepresentation creates a culture that perpetuates inequalities.

Dr. Aha’s “River of Empowerment” metaphor describes her program of research and interest in women’s health, migration, social justice, and equity.

5.3 Narrative #3 Tenure-Track Dr. [concealed for review - pseudonym Dr. Roy]

Dr. Roy is a tenure-track faculty member with research experience and clinical experience as a nurse practitioner. Dr. Roy’s expertise include: 1.) substance use and concurrent mental health conditions; 2.) trauma; and 3.) gender-informed approaches to care. Dr. Roy’s clinical experience translates into her research focus on health equity amongst vulnerable populations. The imagery of a bridge can be used to describe her research program. The purpose of a bridge is to provide passage over an obstacle, which is usually something that is otherwise difficult to cross. Dr. Roy’s research centers on marginalized populations who face various barriers and obstacles to healthcare. In both her clinical and research work, Dr. Roy is guided by her core value of bridging between community-based grassroots programs and larger systems to collaboratively meet the needs of marginalized communities.

In a Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QAC) to examine the processes and approaches used by Ontario Health Teams (OHT) in Canada to balance provincial indicators with local population-specific indicators in the Collaborative Quality Improvement Plans, Dr. Roy and her team identified challenges with balancing the provincial and population-specific indicators, and with integrating the voices of patients, family members and care providers. As Dr. Roy states,

The study was a first step toward working together with people with living and lived experiences from design to evaluation from a partnered approach that is hoped to be embedded in how the MWT-OHT approaches all initiatives.

As an OHT impact fellow with the Mid-West Toronto OHT, I worked on the development and delivery of a Collaborative Quality Improvement Plan that is rooted in collaboration and engage of people with living experience, families, community partners and stakeholders.

This research work demonstrates Dr. Roy’s aim to understand and “bridge” the gap between communities and the larger systems. Dr. Roy’s research highlights and enhances trauma-informed approaches to care to bridge the gap between individual, group, and community levels with the organizational and systems level. At the organizational and systems level, Dr. Roy’s research has also focused on bridging the gap between healthcare staff and managers, by identifying leadership activities that increase managers’ capacity to better support staff in challenging and unprecedented times. As she shares,

As a presenter at the Registered Nurses Association of Ontario’s (RNAO) webinar on supporting workforce mental health, I discussed the impacts of current work environments on nurses’ health and well-being and explored the use of a trauma-informed lens to support mental health amongst nurses.

Finally, the bridge is symbolic of communication, connections, and union. Dr. Roy’s clinical, educational and research work provides a bridge to the care that marginalized populations need, as they often have complex needs due to substance issues, mental health problems, or history of trauma.

5.4 Concluding Synthesis

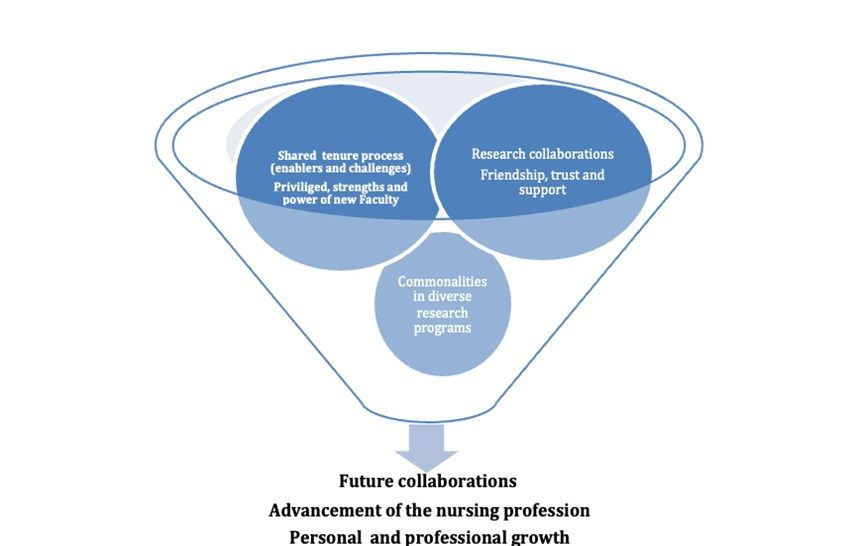

These narratives highlight the academic journeys of three novice tenure-track faculty in creating their programs of research. Each narrative highlights the importance of nurturing research environments that foster academic and practical contributions to nursing and healthcare education (see Figure 1 on the concluding synthesis and what this study aimed to achieve).

6.Analysis

6.1 Narrative Thread #1: Stakeholder Collaboration and Involvement

There is a growing importance of stakeholder collaborations in research and knowledge co-creation. All three participants engage with a range of stakeholders in their research. Such engagement stimulates greater mutual learning and openness to alternative perspectives and worldviews. This can facilitate enhanced knowledge and understanding of concepts, resulting in higher-quality research (Williams et al., 2020). Drs. Kam, Roy and Aha also develop interactive research practices involving other academic members, and they use participatory research methods to engage with community partners and stakeholders. Participatory research is an umbrella term that emphasizes and encourages the engagement of local priorities and perspectives in research (Vaughn & Jacquez, 2020). Participatory research allows for knowledge co-construction through partnerships (Vaughn & Jacquez, 2020).

All three participants have conducted research focusing on individuals and communities experiencing structural vulnerabilities. For example, Dr. Roy uses her extensive experience as a nurse practitioner in the field of substance use and mental health to create meaningful collaborations with stakeholders. Dr. Aha uses critical ethnography to investigate the healthcare needs of refugee women, and those experiencing food insecurity and homelessness. Dr. Kam has conducted research with and collaborated with individuals experiencing social isolation, homelessness, and substance use.

While all three faculty members collaborate with stakeholders and community partners to facilitate knowledge co-creation, there are differences in their approaches and foci. Dr. Kam and Dr. Roy both engage nurses and nursing students in their research projects. However, Dr. Kam’s explicit inclusion of nursing students, and her purpose for including them in her research, differ from Dr. Roy’s. For example, Dr. Kam included nursing students as members of the research team for a national study exploring educational needs in relation to medical and recreational cannabis. Thus, Dr. Kam involves nursing students to co-create knowledge for both educational purposes and nursing practice. In comparison, Dr. Roy includes nurses and nursing students through other methods such as hosting interactive webinars with the Registered Nurses Association of Ontario (RNAO). Dr. Roy explores the use of a trauma-informed lens in supporting workforce mental health and collaborates with nurses, nursing leaders and nursing students to create a culture of knowledge co-creation (Yoon et al., 2019). Finally, although Dr. Aha’s research philosophy does not explicitly state any collaborations with nursing students, she invites students to be research assistants providing extensive hours of mentorship. Despite the differences in their approaches and foci, all three participants engage a diverse range of stakeholders in their research stimulating greater mutual learning, resulting in higher-quality research (Williams et al., 2020).

6.2 Narrative Thread #2: Nursing Policy, Practice and Research Leadership

Nursing practice and research must continue to identify evidence-based improvements to care, and these improvements must be tested and adopted through policy changes across the healthcare system (Duff et al., 2020; Institute of Medicine, 2011). Drs. Kam, Roy and Aha are at the forefront of nursing policy, practice, and research leadership as they promote health and nursing policy and practice through their research. Through the knowledge and use of existing nursing and healthcare policies, the participants can facilitate additional policies development (Labrague et al., 2020). Although the relationship between research and policy is complex, policy makers can use research to formulate solutions to problems and identify future policy actions (Labrague et al., 2020).

Policy operates at different levels of analysis - micro, meso, and macro (West & Scott, 2000). Micro-level policies are more proximal to an individual, such as a smaller group or community. Meso-level policies impact broader networks of people or organizations (Greenfield et al., 2018). At a micro- and meso-level, all participants have engaged in research to improve the health and healthcare needs of individuals, families, healthcare providers, organizations, and communities.

For example, Drs. Kam and Roy have looked at solutions development for individuals experiencing homelessness and/or substance use. Similarly, Dr. Aha’s research has highlighted marginalized populations such as refugees and those experiencing food insecurity. Drs. Aha and Kam recently collaborated with nursing students and community partners on a research project on Ukrainian refugee women. Drs. Kam and Roy have also conducted research on healthcare needs within the profession such as for nursing students and/or practicing nurses. However, Dr. Kam emphasizes nursing education in her research, whereas Dr. Roy’s research focuses on the healthcare needs for care providers through a trauma-informed lens.

All participants disseminate research in a formal manner through scholarly publications and conferences, but also informally through teaching. Dr. Kam disseminates findings to her students in courses focused on acute and life-threatening illnesses, chronic illnesses, as well as leadership and management. Similarly, Dr. Aha is able to disseminate evidence-based findings to her students through courses focused on adult nursing, alterations in health, chronic care, community care and nursing leadership. While Dr. Roy does not formally teach a leadership course, she disseminates her research as a course lead and instructor for mental health promotion and at a graduate-level where she teaches a Nurse Practitioner course.

All three participants also display variations in research dissemination. Dr. Kam is an expert in artistic expressions in research and uses poetry as one dissemination method with her students. Drs. Kam and Roy also disseminate findings through nursing associations such as the Registered Nurses Association of Ontario (RNAO) through webinars or involvement in committees that promote best practices. Both participants also disseminate research with their colleagues in clinical environments. All participants also disseminate research at an international level. For example, Dr. Aha has teaching experiences in other institutions in Canada, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and Jordan, Thus, Dr. Aha has been able to disseminate her interdisciplinary and international research at a macro-level. As faculty members at the forefront of nursing education, practice, research and policy, Drs. Kam, Roy and Aha have all made positive impacts at the policy level.

6.3 Narrative Thread #3: Constructive Epistemological Ontology

Qualitative and mixed-method research designs are common in nursing and healthcare research due to their ability to capture humanness and diverse individuals and contexts (Doyle et al., 2020). All three participants use a qualitative or mixed-method design for most of their research as this recognizes the subjective nature of the problem, and the different experiences of participants. All participants also adopt a similar paradigm for their research. Constructivism is an epistemology that aims to explain how humans learn. Constructivism denies the existence of an objective reality, and emphases the subjective interrelationship between researchers and participants to co-construct knowledge and meaning (Mills et al., 2006). This is evident in all participants' research, as they embed themselves into their research rather than taking an objective stance. In most of their research, participants have used similar data collection methods such as artistic expressions, interviewing, focus groups, and document analysis.

Despite these similarities, there are differences in their qualitative research. For example, Dr. Kam often uses grounded theory to shape her research. In her doctoral study, Dr. Kam used Constructivist Grounded Theory to explore the role of patients within interprofessional teams in primary care (Metersky et al., 2021). In contrast, Dr. Aha often uses ethnodrama or ethnography to study a specific group within a culture for many of her projects. For example, Dr. Aha examined the use of a blended approach of critical ethnography and intersectionality to advance refugee women’s research and inform healthcare and nursing practice (Al-Hamad et al., 2022). In contrast, Dr. Roy employs a case study design to guide her research. In her doctoral thesis on women’s substance use programs, Dr. Roy used a case study design and a Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) method. Although there are differences in the research methods preferred by each participant, there are opportunities for collaboration.

7.Discussion

7.1 Interpretation of Findings

This study revealed three key narrative threads among three novice tenure-track nursing faculty: stakeholder collaboration and involvement, nursing policy practice and research leadership, and structures and facilitators for collaboration and constructive epistemological ontology. The findings highlighted how each faculty member engages with a variety of stakeholders to enrich their research and teaching practices. This aligns with previous research suggesting that stakeholder collaboration enhances research quality and impact (Thomas, Hooker & Schmittdiel, 2024).

The participants’ narratives revealed a strong commitment to influencing nursing practice and policy through their research. This reflects the role that evidence-based research plays in shaping healthcare policies and practices. The ability of novice faculty to contribute to policy and practice underscores the importance of providing them with platforms for policy advocacy and leadership development within their institutions.

Our findings also highlight the participants’ use of constructivist approaches to understand and interpret their professional experiences and research phenomena. This is consistent with the constructivist belief that knowledge is constructed through social interactions and shaped by individual experiences (Mills et al., 2006). Such epistemological stances are crucial to develop a deep understanding of complex issues prevalent in nursing and healthcare.

7.2 Implications

This study sed insight on collaboration among three novice tenure-track nursing faculty members. Future research can explore the benefits and outcomes of such collaborations by identifying commonalities and opportunities for future collaborations.

Particularly, it can focus on establishing platforms that facilitate exchange of ideas, resources, and best practices between researchers with similar research programs. Also, the study findings can inform the design and implementation of interdisciplinary training programs for new faculty members. Institutions can develop initiatives that promote such collaborations, fostering a culture of collaboration among new faculty members. Particularly, they can incorporate mentoring programs that pair novice faculty members based on their research interests. This can provide opportunities for knowledge exchange, support, and guidance, enhancing professional development. From a practice and policy perspectives, the study's findings can inform institutional policies and practices to support faculty collaborations. Institutions can provide resources, grants, and dedicated time for collaborative research projects, recognizing their potential to enhance research impact. This can lead to a more vibrant research community and increased competitiveness in securing external funding.

8. Final Considerations

Transition into a tenure-track research position enables doctorally prepared nurses to build their research programs (Viveiros et al., 2021). Although there is an abundance of literature on new faculty collaborations with senior, tenured faculty, there is a lack of literature on collaboration between novice faculty members. This analysis of three faculty members’ research programs demonstrates that collaboration between new faculty members is possible, leading to successful initiatives, and can further advance nursing education, practice, policy, and research. Through Narrative Inquiry, participants shared their programs of research, and three key narrative threads were identified: stakeholder collaboration and involvement; nursing policy, practice, and research leadership; and constructive epistemological ontology. This will add to research on novice faculty with novice faculty partnerships and the potentials these partnerships can have in advancing nursing research. The transition into an academic tenure-track research position can be a challenging and complex process (Bice et al., 2019). Collaboration and support between and amongst new faculty members can help ease some of the challenges experienced in their first few years of academia, but also inform the development of innovative collaborative research projects.