1. Introduction

As a profession, nursing has kept the pace of development aligned with the growing demands of healthcare and the complexity of clinical contexts (Chaves et al, 2017). In this process, supervision has always been involved in its more instrumental and strategic version, adding at the same time a more reflective dimension, which seems to have helped overcome some issues of an administrative nature, promoting professional autonomy.

Until the end of the 19th century, the administrative model of reorganization between the nursing school and the hospital was similar, mostly justified by the concern of training future nurses capable of responding immediately to the needs of the clinical practice context. At this level, their inter-organizational articulation did not appear as a problem in terms of collaborative practices (Macedo, 2012). Currently, with the clear attribution of competencies and differentiation of functional responsibilities, including a specific space recognized for the academy and the hospital, the construction of collaborative practices between supervisors (professors and nurses), students, and health organizations seems to reveal a process of harmonization and divergence (Macedo, 2011). Thus, an important dimension of analysis emerges concerning the link between academia and health organizations, assumed as a factor in the early development of areas of action in the clinical practice of future nursing professionals.

The combination of training between academia and health organizations is particularly appreciated because it allows students to socialize in a professional context. If, in some way, the student is confronted with a set of organizational rules and protocols, they also live experiences with the person and their family throughout their life cycle, witnessing and participating in the management of health and disease processes. The collaborative practice of the student with nursing professionals within the health team, in the provision of care centred on the person and their family, allows him/her to evolve in the process of autonomy and translation of knowledge. This is an important issue in the acquisition of professional and ethical skills, which characterize the nursing profession (Conselho Nacional de Educação, 2023; Rouhi-Balasi et al, 2020).

During the clinical education/internship time, students are accompanied by supervisors (professors and/or nurses), discussing and analysing critical situations whose benefits are well known, especially regarding the development of reflective competencies (Vieira, 2006). Supervisors can motivate students to the field of analysis, helping them to observe, question and confront, interpret and reflect, and seek the best solutions in health contexts. Although some studies have recognized the strategic value of the inter-collaborative process between academia and health organizations, the phenomenon has barely been explored (Macedo, 2012). Others agree that the practices of collaborative supervision still lag far behind theoretical developments in the field (Alarcão et al., 2013). This acknowledged lack of empirical analysis seems to be an urgent call for future research in the area, contributing to a positive effect on the standards of students' education and health organization needs.

In fact, due to the poor appropriation of supervision practices and inter-organizational articulation by supervisors, there is currently an emergency in establishing the training suitability of clinical contexts and the intensification of policies to evaluate the quality of research and education (Ordem dos Enfermeiros, 2017). These are structural dimensions for guaranteeing the safety of care, reducing error occurrence, length of hospital stays, lower levels of health satisfaction, staff turnover, and mortality rates (Green et al, 2015). In sum, collaboration allows organizations and all those involved to achieve more than they could on their own, making them better able to form alliances and strategies that are essential for innovation and learning (Green et al, 2015).

Bearing this in mind, and according to the different organizational models it is possible to integrate conceptual contributions that harmonize the relationship between hospital organization models and processes of nursing supervision (Tanner & Tanner, 1987), whose interactions influence the skills profile of the actors involved (Harris, 2002). As clarified by Harris (2002), the interpretation of organizational models, defined as a set of work practices that are accepted and integrated into the daily lives of employees, influences the appropriation of supervisory intervention.

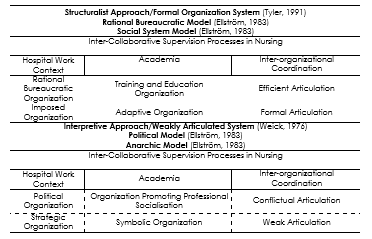

The clinical supervision experience of the project participants is broad and diverse, with some having carried out research in the area of nursing supervision and participated in multidisciplinary pedagogical projects at UMinho (Transformative Pedagogy at the University: Reflecting, (Inter)Acting, Reconstructing; Nursing Supervision: New perspectives for change). For example, there is a theoretical-methodological essay previously developed by Macedo (2012), in which some dimensions of the rational-bureaucratic organisational model (Ellström, 1983) are highlighted, due to the emphasis on efficiency, effectiveness and productivity in supervisory practices. In this case, the learning process is based on the observance of specific behavioral objectives, and control mechanisms capable of monitoring their degree of compliance. Conversely, the social system model (Ellström, 1983), whose organization is defined as a cooperative system (Barnard, 1971), turns the work context into one of strong socialization. This claims to be the true model of clinical supervision (Tanner & Tanner, 1987) with a recognized culture of demonstration and guided learning. Lastly, the political and the anarchic model (Ellström, 1983), based on a set of indicators, including the heterogeneity of individuals and groups with different objectives and preferences, reveal a weaker control mechanism than the rational-bureaucratic one. In this alignment emerges the model of supervision as a developmental process (Tanner & Tanner, 1987), based on the valorisation of symbolic representations, games, or interactions whose line of learning is more reflective, humanistic, developmental, and socio-constructivist.

The preliminary analysis of these theoretical models allows for a unique reading of the current situation in health organizations and academia about the implementation of supervision measures driven by quality criteria. However, in some contexts, the inter-organizational collaborative processes are being neglected (Macedo, 2012). At this level, we propose to understand the possible dimensions of inter-organizational collaborative practice (academia and hospital), identifying its possible processes and results capable of supporting the safety of clinical procedures and effectiveness.

2. Materials and Methods

The present research is part of a project that took place in a Higher Education Organization in the north of Portugal between September 2022 and September 2023, entitled Clinical Supervision in Nursing Collaborative Experiences (ECO), under the Program to Support Innovation Projects and the Development of Teaching and Learning (IDEA). Its main objective was to develop and evaluate an intervention program focused on the theoretical and practical training of supervisors grounded on a research-intervention project in a clinical context. We intended to contribute to debating supervision and collaborative strategies, improving the interpretation of the experience of those involved in the supervision process (professors, nurses, and students).

The ECO project used a mixed-methods approach consisting of two concurrent phases: quantitative and qualitative. The quantitative component allowed for an analysis of the program's effectiveness in improving supervisory practices, particularly in the context of interactions between the academy, supervisors, and nursing students. Meanwhile, the qualitative approach, utilizing the focus groups (FG) method, aimed at a group of seven nurse supervisors, conveniently selected according to their interest in taking part in the session, effectively addressed the core questions of this study, namely:

- What representations do supervisors have of their inter-organizational collaborative practice?

- What representations do supervisors have of the management models present in the inter-organizational relationship between the hospital and academic contexts?

In order to respect the principle of group homogeneity (Krueger, 2009), the following inclusion criteria were met: participants must belong to a hospital setting that integrates a collaborative supervision process with academia.

All supervisors were given the same opportunity to participate, with the possibility of organising additional focus group sessions; however, only seven nurses showed interest in the focus group session, which was an ideal number as it ensured an environment conducive to in-depth discussion and active participation. It meant that each participant had ample opportunity to contribute and that the nuances of their experiences could be explored in depth.

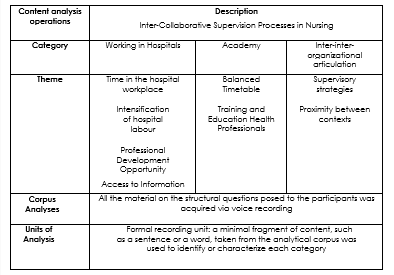

For analyzing supervisors' representations of the inter-collaborative process, we used the empirical model proposed by Macedo (2011), as we may see in Table 1.

Table 1 An empirical model for analyzing supervisors' representations of inter-collaborative processes

The previous archetype represents two approaches to reading the inter-collaborative process, namely: the Structuralist/Formal Organization System (Tyler, 1991) and the Interpretive/Weakly Articulated System (Weick, 1976). In the first one, the hospital work context assumes theoretical positions with the rational bureaucratic and social system imposed by the use of strict norms/rules that guide the behavior of individuals in the organization. As well in academia, once this organization is recognized as formative promoting adaptive behavior to norms through shared consensus and a culture of trust between members. This approach seems to lead to articulations characterized by efficiency and protocol formality. In the second approach, it is represented as a political and strategic form, whose basis of legitimacy is reflection, characterising the hospital work context. Structures and processes are oriented towards the environment, highlighting the ambiguous and political dimensions of organizations, while promoting criticism and conflict. Hypocrisy is a fundamental behavior in a political organization (Brunsson, 2006). At this point, academia is a promoter of professional socialization; it enables inter-collaborative and inter-professional actions, as well as symbolic ones, which are fundamental to the legitimization of the organization. Commonly, it is possible to observe a weak articulation, characterized by unclear objectives, technologies, and strategies (Cohen et al., 1972). However, this type of articulation, which is considered weak, does not take on a pejorative meaning capable of undermining processes of clinical supervision. On the contrary, a political and emancipatory dimension of the actors can be present, allowing for interactive supervision processes that overcome dualisms between the school and the hospital, as well as getting to know and intervening in organizations.

2.1 Focus Group technique

The FG as a data collection tool and as a technique used in a single session has its benefits, of which the best known is the interaction of the participants, considered the main difference that distinguishes it from a collective interview. In this sense, the methodological procedure was carried out through the interaction of the group on a given topic/topic proposed by the researcher (moderator, facilitator), recognizing his active role in stimulating all the participants to obtain data generated by the discussion (Morgan, 1996). The script created for the FG session was structured around systematised questions, largely in line with the theoretical framework we proposed (Macedo, 2013; Macedo, 2012). Of the various categories defined a priori, the following stands out as the main dimension of analysis: Inter-Collaborative Nursing Supervision Processes (Table 2). The content analysis followed the operational assumptions of Bardin (2016).

2.2 Preparing the Focus Group Session

A single FG session requires fundamental decisions that will influence the outcome of the group and the data analysis. Once the clinical supervisors accepted the invitation, they were informed of the location, date, and duration of the session.

The main researcher and two moderators, who supported all the logistics involved (from managing the room to controlling the recording), conducted the FG. Aware that a single one-hour session would not always be able to provide enough diverse and relevant data for a robust analysis (Souza, 2020), the group was informed about the possibility of taking part in further meetings. However, achieving data saturation in the first session allowed us to fulfill the research objectives outlined. Data saturation was achieved primarily through the deliberate design and structure of the session. The theoretical framework that underpinned the study was carefully selected to align with the research objectives and guide the discussion toward specific and relevant topics. In addition, the homogeneity of the group of participants, who shared similar clinical roles and experiences, allowed for a focused and comprehensive conversation. This shared background facilitated rapid consensus on key issues, reducing the need for lengthy discussions. The facilitators also played a critical role by effectively managing the discussion and ensuring that each participant had the opportunity to contribute within the limited time frame. Together, these elements ensured that the one-hour session was sufficient for a thorough exploration of the relevant issues, resulting in early data saturation. This outcome is consistent with the conceptualization of data saturation discussed by Saunders et al. (2017), where saturation refers to the depth and richness of the discussion, not simply the quantity of data, and represents the point at which additional data collection ceases to yield new insights.

2.3 Data processing

As All the cutouts obtained from the testimonies were identified by the letter S (Supervisor), followed by the numerical sequence that represented the order in which the different participants intervened. The main category showed themes or items of meaning, as proposed by Bardin (2016), making it possible to operationalize the sentence as a coding unit from the participants' statements. For the data analysis we used systematic and objective procedures to describe the content of the speeches, making it possible to infer knowledge about the conditions of their production. At this level, we followed the chronological organization of the three phases of content analysis: pre-analysis; exploration of the material; treatment of the results, inference, and interpretation (Bardin, 2016). No software was used in the content analysis procedure. The content analysis according to Bardin's assumptions was carried out by the principal investigator and validated by two members of the project who were also present at the FG session.

3. Results

The FG participants in the session were 86% female, with an average age of 40 (SD=6.8) and 17.5 years of average professional activity (SD=7.2).

As can be seen in Table 3, the content analysis of the participants' discourse (the coding units) allowed us to systematise the data as follows, in terms of the categories, the themes identified and our main dimension of analysis.

4. Discussion

The participants’ speeches seem to show that the hospital work context is essentially oriented towards a rational-bureaucratic model, inducing supervision profiles that are closer to effectiveness, efficiency, and productivity, in which time has a special status, as a means of control. At this level, we identified the rationalism and rationalization present in modern organizations where the calculation of time and the economic cost associated played a significant role (Fox, 1999; Fox, 1991; Weber, 1976).

In these organizations, specific rules are formulated to control and unify the behavior of its members. In this case, there is no need for decision-making, so most processes are irrational and can limit initiatives (Brunsson, 2006). The configuration of some dimensions of rationality is represented in the supervisors' speeches, by the bureaucratic characteristics present in the hospital organization, which is/are(?) an example of the computerized procedures and care solutions with restricted access, capable of creating coercion and control mechanisms, as a way of guaranteeing organizational efficiency (Weber, 1976). Some of the constraints present in this organization are mentioned as hindering learning, such as access to information and the intensification of work. About academia, it is seen as fundamental in the training of health professionals, and specifically of clinical supervisors, and in this context, time is seen as both necessary and balanced. Two of the participants emphasise the interaction that should exist in the classroom and during simulated practice between nursing students and students from other areas of health, so that interprofessional learning can be provided from that point on.

Although only one supervisor explicitly points to the importance of articulating the practical context with the academic one, referring to the need for health organisations to invest more in inter-collaborative processes, some dimensions of the political and anarchic model seem to emerge (Macedo, 2012). This organizational structure is more ambiguous, and its processes are oriented towards an open system. The viability and the success of inter-organizational relationships depend on the ability of both central and peripheral partners to acknowledge and address such ambiguities, requiring networked contributions to realize collective and individual interests (Palumbo, et al., 2020; Van Dale, et al., 2020).

It is therefore understandable that some health services, replete with safety rules and procedures, such as the operating theatre, can be poorly articulated (Weick, 1976), coexisting with the recognised ‘hypocrisy’ of unexplained or planned inter-collaboration within the hospital and externally with academia. However, the existence of ‘hypocrisy’ within an organisation is seen as fundamental in ‘political organisation’ (Brunsson, 2006). The dimensions highlighted by the players in this last organisational management model lead us to believe that there is the possibility of creating spaces for supervisory processes free of constraints, generating a certain degree of autonomy for supervisors and supervised. In this scenario, the educational and training environment in a hospital context will become more interactive and reflective, in a more developmental and socio-constructivist line of supervision.

Regarding inter-organizational articulation, the supervisors mention the desire for a strong mechanism of control which seems to us, in the light of our conceptual theoretical framework, to fit into dimensions of the bureaucratic rational model (Macedo, 2012), characterized by efficiency and protocol formalities (formal organization system) (Tyler, 1991). However, we also realize that the discourses indicate dimensions of the interpretative approach. Although the current approach indicates a weakly articulated system, free of normative procedures (Weick, 1976), it does bring some benefits to organizations, such as greater proximity and collaborative work, and communication between academia and the hospital. This means that we can be dealing with an inter-organizational articulation that takes power relations and conflict into account and, at the same time, a weak articulation in which organizational protocols between the parties are rarely put into practice.

This conceptual level transposed to the context of action can give rise to inter-collaborative supervision processes of different styles, allowing those involved in supervision to act in the face of confrontation and develop their emancipatory capacities, through a shared vision, leadership, member characteristics, organisational commitment, available resources, clear roles/responsibilities, trust and clear communication (Seaton, et al., 2018). In this sense, we seem to be following a line of development that facilitates learning and collaborative experiences. In this sense, it doesn't seem necessary to balance power relations in order to improve collaborative processes. That it would be an error for collaborative interventions to focus only on improving the exchange of information, without considering how everyday communication is constructed in a broader social context (Noyes, 2022). Thus, improvements in collaborative care require daily group interactions that can challenge and reinforce hierarchical power relations (Noyes, 2022). In this context, the use of supervisory strategies is essential to boost collaboration and bring the actors from the two contexts closer together. They are also seen as technologies that allow for interaction and empowerment of the actors. Some examples mentioned by the FG participants are systematic feedback to increase reflection, face-to-face and Zoom meetings, the use of email, and access to documents to gather information.

In sum, we realize/acknowledge the bipolarity of the presence, on the one hand of dimensions from the rational-bureaucratic model, and the other, related to political, and anarchic models. In other words, supervisors expressed their desire for inter-organizational coordination that worked according to clear and consensual objectives, with compulsory activities organized in a single plan. This seems to be linked to the hospital's more rigid and hermetic internal procedures, where time appears to be a fundamental element for the fulfilment of objectives. Conversely, there seem to be practices associated with the dimensions of the political and anarchic model. The supervisors showed a certain lack of clarity and ambiguity in the supervisory processes because of fragile coordination at certain times, interfering with the supervisory processes and inter-organizational coordination (academia and hospital).

The supervisors' statements also recognize the importance of academia as a promoter of articulation within the clinical context, enhancing ways of thinking, planning, and acting with empathy, responsibility, and care for the environment and public health. This is aligned with the development of the European sustainability competence framework, one of the political actions defined in the European Green Deal (Bianchi, 2022). The document sheds light on actions or programs focused on sustainability, and in this sense, we can place some of our project interventions such as inter-collaborative activities with clinical supervisors once we aim to promote references and opportunities for learning and evaluating recognized processes of education and training (Bianchi, 2022). We are aware that academia enables professional socialization and favours inter-collaborative and inter-professional actions, as well as symbolic ones that are fundamental to the health organization.

5. Conclusion

Nursing supervision and collaborative processes in clinical training and internships allow us to outline, within certain limits, some similarities and differences between academia and the hospital.

Inter-organisational collaboration in nursing supervision as a dimension of analysis points to spontaneous evidence that brings the two organisations closer together in two areas: care and education. This dimension highlights categories

This dimension highlights categories of current collaborative practice based on the representations of nurse supervisors. According to our theoretical framework, these categories seem to result in the approximation of actions and logics related to the rational-bureaucratic organisational model and the political and anarchic model.

The results identify additional issues to be considered in future collaboration processes and to be taken into account by those in charge of these organisations.

Other aspects with future implications for research and health promotion are the potential threats, highlighted by the time dedicated to supervision and access to information in the hospital context, and, on the other hand, the opportunities for articulation, highlighted by the importance of involving the various players in each context, both in planning training programmes and in the use of supervision strategies. Inter-organisational coordination seems to be an emerging area of interest in the health field and is considered fundamental in health promotion practices.

Finally, we must highlight some of the study's limitations, which were related to the number of clinical contexts participating, since data collection was limited to the hospital setting. In this sense, it is proposed that other studies be carried out that include other health contexts, as well as the inclusion of participants from other multidisciplinary teams.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, A.M, and A.T.; methodology, A.M, and A.T.; validation, A.M, and A.T.; formal analysis, A.M, and A.T; investigation, A.M, and A.T.; data curation, A.M, and A.T; writing-original draft preparation, A.M, and A.T.; writing-review and editing, A.M and A.T; supervision, A.M, and A.T.; project administration, A.M..; funding acquisition, A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement: The study was conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Minho (protocol code 133/2022 on 13 May 2022).

Informed Consent Statement: Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement: Data is unavailable due to the privacy of all the participants.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements: We thank the participants in the study for their co-operation.

Funding: The APC was funded by the Foundation for Sciences and Technology (FCT). Health Sciences Research Unit: Nursing (UICISA: E), Nursing School of Coimbra; Work from an IDEA-funded project, Universidade do Minho.