Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

GE-Portuguese Journal of Gastroenterology

versão impressa ISSN 2341-4545

GE Port J Gastroenterol vol.25 no.4 Lisboa ago. 2018

https://doi.org/10.1159/000484093

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Can Water Exchange Improve Patient Tolerance in Unsedated Colonoscopy? A Prospective Comparative Study

Poderá o Método de Troca de Água Melhorar a Tolerância do Doente na Colonoscopia sem Sedação? Estudo Prospectivo Comparativo

Richard Azevedo, Cátia Leitão, João Pinto, Helena Ribeiro, Flávio Pereira, Ana Caldeira, António Banhudo

Department of Gastroenterology, Amato Lusitano Hospital, Castelo Branco, Portugal

* Corresponding author.

ABSTRACT

Background & Aims: Unsedated colonoscopy can be painful, poorly tolerated by patients, and associated with unsatisfactory technical performance. Previous studies report an advantage of water exchange over conventional air insufflation in reducing pain during unsedated colonoscopy. Our goal was to analyze the impact of water exchange colonoscopy on the level of maximum pain reported by patients submitted to unsedated colonoscopy, compared to conventional air insufflation. Methods: We performed a single-center, patient-blinded, prospective randomized comparative study, where patients were either allocated to the water group, in which the method of colonoscopy used was water exchange, or the standard air group, in which the examination was accomplished with air insufflation. Results: A total of 141 patients were randomized, 70 to the water and 71 to the air group. The maximum level of pain reported by patients during unsedated colonoscopy, measured by a numeric scale of pain (0–10), was significantly lower in the water group (3.39 ± 2.32), compared to the air group (4.94 ± 2.10), p < 0.001. The rate of painless colonoscopy was significantly higher in the water group (12.9 vs. 1.4%, p = 0.009). There were no significant differences between the two groups regarding indications for the procedure, quality of bowel preparation, cecal intubation time, withdrawal time, number of position changes, adenoma detection rate, and postprocedural complications. Only the number of abdominal compressions was significantly different, showing that water exchange decreases the number of compressions needed during colonoscopy. Conclusions: Water exchange was a safe and equally effective alternative to conventional unsedated colonoscopy, associated with less intraprocedural pain without impairing key performance measures.

Keywords: Colonoscopy, Water exchange, Air insufflations, Sedation, Pain

RESUMO

Introdução e objectivos: A colonoscopia sem sedação pode constituir um procedimento doloroso e mal tolerado pelo doente, associando-se a um desempenho técnico subóptimo. Vários estudos demonstraram o benefício do método de troca de água, comparativamente à colonoscopia convencional com insuflação de ar, na redução do nível de dor na colonoscopia sem sedação. O objectivo deste trabalho foi analisar o impacto do método de troca de água no nível máximo de dor referido pelos doentes submetidos a colonoscopia sem sedação, comparativamente à colonoscopia convencional com ar. Métodos: Estudo comparativo unicêntrico, prospectivo e randomizado, cego para o doente, no qual os doentes foram alocados ao grupo água, no qual se utilizou o método de troca de água, ou ao grupo ar, no qual se utilizou a insuflação de ar. Resultados: Foram randomizados 141 doentes, 70 no grupo água e 71 no grupo ar. O nível máximo de dor referido pelos doentes submetidos a colonoscopia sem sedação, avaliado através de uma escala numérica de dor (0–10), foi significativamente inferior no grupo água (3.39 ± 2.32), comparativamente ao grupo ar (4.94 ± 2.10), p < 0.001. A taxa de colonoscopia indolor foi significativamente superior no grupo água (12.9 vs. 1.4%, p = 0.009). Não se verificam diferenças significativas entre os dois grupos relativamente à indicação do exame, qualidade da preparação intestinal, tempo de entubação cecal, tempo de retirada, número de mudanças de posição, taxa de detecção de adenomas, assim como complicações no pós-procedimento. Apenas o número de compressões abdominais foi significativamente diferente, verificando-se que o método de troca de água reduziu o número necessário durante a colonoscopia. Conclusões: O método de troca de água é seguro e constitui uma alternativa igualmente eficaz à colonoscopia convencional sem sedação, associando-se a uma menor dor durante o procedimento, sem comprometer as medidas de desempenho na colonoscopia.

Palavras-Chave: Colonoscopia, Troca de água, Insuflação com ar, Sedação, Dor

Introduction

Colonoscopy plays a major role in the diagnosis and treatment of colorectal diseases [1, 2], being currently accepted as the reference standard method for colorectal cancer screening [1]. Therefore, the annual number of colonoscopies performed is rapidly increasing [2].

However, colonoscopy is an invasive and often painful examination, causing anxiety and compromising patients tolerance and cooperation with the procedure [2]. To overcome that, there has been an increase in deep sedation colonoscopy in recent years, even for routine procedures such as screening and surveillance colonoscopies [3], as it minimizes discomfort and improves tolerance, essential aspects for a successful and safe examination and compliance with subsequent follow-up.

Still, 4 decades after the birth of colonoscopy, the role of sedation is still a matter of debate, as unsedated but well tolerated procedures might play an emerging role [3]. Despite its beneficial aspects, deep sedation has also some disadvantages that cannot be ignored. Colonoscopy with sedation is associated with an increased risk of complications [4], additional costs and longer postprocedural recovery times [5], requiring a greater time commitment from the patient and the endoscopy team [6].

On the other hand, sedation-free colonoscopy is associated with less resource consumption, no need for recovery rooms and postprocedural monitoring, thereby reducing the need for nursing care and increasing the efficiency of endoscopy services [3]. For the patient, unsedated colonoscopy decreases recovery time, having less impact on patients daily activities and work, especially for those healthy working subjects undergoing screening examinations [3]. Thus, a method that minimizes pain and discomfort, allowing colonoscopy with minimal or no sedation, is of major interest.

Procedural discomfort and pain are caused by the stretching of the intestinal wall, mainly during lumen insufflation and scope insertion [6]. Air insufflation (AI) causes not only local but also proximal colonic distention, elongating and pushing it upwards, which may lead to loop formation and tight bends [7]. To overcome that, several alternative luminal distention techniques have emerged.

Water-assisted colonoscopy, first described in 1984 as an auxiliary method to facilitate progression of the colonoscope through the sigmoid colon in patients with severe diverticular disease [8], is gaining increasing popularity as an alternative method to reduce patients discomfort and need for sedation in unsedated and minimally sedated patients [5]. This endoscopic method, in which progression is performed with water infusion instead of AI [9], encompasses 2 major techniques: water immersion (WI) and water exchange (WE).

WI is characterized by the infusion of water to facilitate cecal intubation, with limited use of gas insufflation when necessary, and removal of water during withdrawal [7]. In the WE technique, the infusion and suction of water is performed during the insertion phase, in addition to suctioning of any retained pockets of air [5]. It is characterized by a gasless insertion of the colonoscope in clear water, minimizing distention and maximizing cleanliness during the insertion phase [7]. In both methods, withdrawal is performed with gas insufflation (air or CO2) in order to distend the lumen for standard exploration. Although these are distinct techniques, in daily practice many procedures may combine both methods [5].

Potential benefits of water-assisted colonoscopy include straightening and opening of the sigmoid colon because of the weight of water, reducing spasm, avoiding air-induced distention and elongation of the colon and reducing patient discomfort [10].

Several meta-analyses [11–13] have consistently shown that water-assisted colonoscopy significantly reduces discomfort and pain in patients undergoing colonoscopy with minimal or no sedation, without affecting cecal intubation time and intubation success rate. Water-assisted colonoscopy, as a feasible and easy to learn method for both experienced [14] and inexperienced [15] endoscopists, is a promising approach for improving clinical and patient-related outcomes in colonoscopy without deep sedation.

Our main goal was to evaluate the impact of WE colonoscopy on the maximum level of pain reported by patients submitted to unsedated colonoscopy, compared to conventional AI, by performing a patient-blinded, randomized, comparative study.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

The present study reports a single-center, prospective, patient-blinded, randomized comparative study conducted at the Amato Lusitano Hospital, between January 2015 and December 2016. Colonoscopies were performed by 1 senior gastroenterologist, with more than 10,000 colonoscopies performed, and by 4 trainee gastroenterologists, with different levels of experience but all with a minimum of 250 total colonoscopies without sedation performed. All the operators completed a training period including at least 50 colonoscopies using the WE method, described by Leung [16], before being considered eligible to participate in the study. Patients enrolled in the study were allocated to either the water group, in which endoscopic examination was performed using the WE method, or the standard air group, in which the examination was performed with AI. The colonoscopists were blinded to the bowel preparation used.

Study Population/Patients

Consecutive outpatients, aged 18–90 years old, referred for total unsedated colonoscopy were eligible for participation. Exclusion criteria included: previous colorectal surgery; previous indication to perform intravenous sedoanalgesia or deep sedation; inadequate consumption of bowel preparation; patients with heart failure, advanced pulmonary or renal disease (ASA physical status class III and IV); patients unable to complete a questionnaire and patients who refuse or are unable to give informed consent.

Randomization

Patients meeting the inclusion criteria who signed an informed consent were enrolled and randomized 1: 1 to the WE (water) or the AI (air) colonoscopy group based on a simple computer-generated list. The allocation was kept in a sealed envelope for each patient and opened by the assisting nurse in the pre-endoscopic evaluation. Patients and health workers, but not gastroenterologists or nurses, were blinded to the method of luminal distension used during colonoscopy.

Endoscopic Procedure

All participants were given verbal and written information to accomplish a 2-day low-residue diet (avoid soup, vegetables, fruits and seeds) before colonoscopy and to ingest a 4-L polyethylene glycol-based bowel preparation or a sodium picosulphate-based preparation, administered in the previous late afternoon. All colonoscopies were performed in the morning. After admitting the patient to the preprocedure evaluation, the nurse presented the study and obtained the informed consent from the patient. Demographic data, previous pelvic and abdominal surgery, previous colonoscopies, indication for colonoscopy, comorbidities, current medication, as well as anxiety level prior to the procedure were recorded. After a digital rectal examination, the standard adult variable stiffness colonoscope (CF-HQ185, Olympus®) was inserted. Colonoscopy began with patients in the left lateral position. Patients were blinded to the performed modality, and the monitor was concealed from their view.

In the water group, AI was turned off before starting the procedure. After reaching the rectosigmoid junction, the colon was irrigated with water at room temperature using a foot switch-controlled pump (Olympus® OFP2). Water was infused throughout the colon to distend the lumen sufficiently to allow progression of the colonoscope. If the colonic lumen could not be clearly seen, a maximum of 3 AIs, lasting no longer than 10 s each, were allowed to progress with the colonoscope. If further AIs were required, the WE method was considered to have failed.

The infused water, fecal waste and air pockets were removed during insertion as much as possible. Once the cecum was reached, the air pump was switched on and the colon was fully distended. Cecal intubation was defined as the passage of the scope tip beyond the ileocecal valve with visualization of the cecal appendix.

In the Air group, colonoscopy was performed according to the usual method, using the minimum AI required to reach the cecum. In both groups, the withdrawal phase lasted at least 6 min and was performed using room air insufflation to obtain adequate lumen distention. Abdominal compressions and position changes were applied as needed in the two groups and recorded in a subsequent questionnaire applied to the gastroenterologist. Polypectomies were performed during the withdrawal phase. The polyps were classified in size, configuration and location in the colonoscopy report. Conscious sedation (intravenous midazolam plus fentanyl) was offered and administered on-demand at the patients request during the procedure.

Evaluation of Pain

Immediately after colonoscopy, the pain experienced during the examination was assessed by the patient, with the help of a room assistant blinded to the insertion method, using a numeric scale of pain (0 = no pain; 5 = moderate pain; 10 = worst possible pain). Patient-perceived difficulty and willingness to repeat the examination were also evaluated. In all cases, it was ensured that the endoscopist was not in the room at the time of the questionnaire.

In addition, the gastroenterologist filled out a questionnaire about the total colonoscopy time (intubation and withdrawal time), level of technical difficulty during the insertion phase, number of position changes, number of abdominal compressions performed and any adverse effects that might have occurred during the procedure (transient oxygen desaturation and vagal reaction).

Study Endpoints

The primary endpoint of this study was to evaluate whether the use of the WE method in unsedated colonoscopy could reduce the maximum level of pain reported by the patient, when compared to conventional AI colonoscopy.

Secondary outcomes included preprocedural anxiety level, cecal intubation rate, insertion and withdrawal time, bowel preparation evaluation (according to the Boston Bowel Preparation Scale), need for patient repositioning and abdominal compression, difficulty from the endoscopists point of view; need for on-demand intravenous sedation and adenoma detection rate. Also, patients experience (perceived difficulty and willingness to repeat the examination) was recorded.

Sample Size Calculation

For the sample size calculation, it was assumed that the mean value of pain perceived by patients submitted to unsedated colonoscopy in the outpatient setting, at our institution, was 4.90 ± 2. These data were obtained through a previous study performed by the same research team that aimed to determine the predictive factors of pain during unsedated colonoscopy with AI.

Assuming that the water method could improve this value in at least 20% of cases, according to the information obtained in the recent literature, it would be necessary to include a minimum of 33 patients in each study group for a power of 90% and a significance of 0.05.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS v.23 (IBM Corporation, New York, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics were analyzed for each collected variable (mean and SD for continuous variables and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables). Continuous variables were compared between groups with independent-samples t test or Mann-Whitney U test. For categorical variables, the χ2 test or Fisher exact test were used, as appropriate. A p value <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Ethical Considerations

Our study was approved by the institutional ethics committee of our Hospital and data collection started after approval has been given. There was no public, prospective registration of the trial. All patients signed an informed consent form at the time of the preprocedure interview, after clarification of any possible doubts.

This study was funded through a grant for research projects promoted by the Portuguese Society of Digestive Endoscopy, awarded in 2014 after submitting the project for evaluation.

Results

Patients Baseline Characteristics

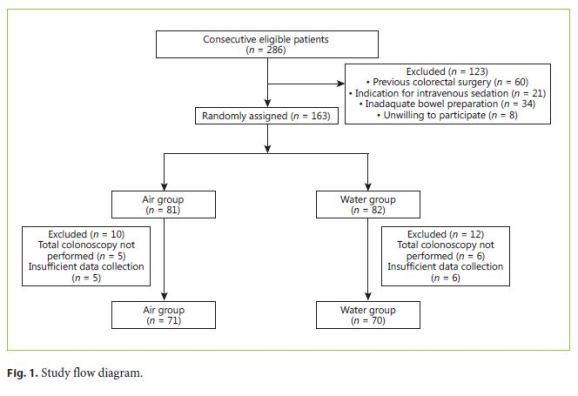

A total of 286 patients were assessed for eligibility, and 163 patients were randomized to undergo colonoscopy with WE (water) (n = 82) or AI (air) (n = 81) (Fig. 1). Of 163 colonoscopies, cecal intubation was not achieved in 11 cases: 5 cases in the air group, because of technical difficulties, and 6 cases in the water group, because more than 3 AIs were performed, and it was considered failure of the WE method. Furthermore, insufficient data collection precluded the inclusion of 11 patients. Thus, these patients were excluded from further analysis.

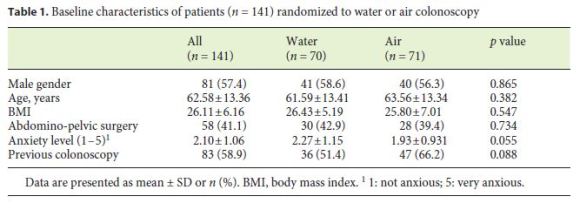

As a result, 71 cases in the air group and 70 cases in the water group were analyzed. The baseline characteristics including gender, age, body mass index, history of abdominal or pelvic surgery, history of previous colonoscopy, and preprocedural anxiety level were comparable between the two groups (Table 1).

Patient Pain and Experience

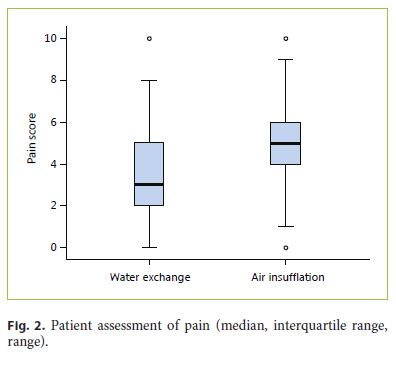

The primary endpoint, maximum level of pain reported by the patient during unsedated colonoscopy, measured by a numeric scale of pain (0–10), was 3.39 ± 2.32 in the water and 4.94 ± 2.10 in the air group, and the difference was statistically significant, p < 0.001 (Fig. 2). Furthermore, the rate of painless colonoscopy was significantly higher in the water group (12.9%), compared to the air group (1.4%) (p = 0.009). Among the 141 patients enrolled in the study, only 3 reported the maximum level of pain: 1 patient (1.4%) in the water group and 2 patients (2.8%) in the air group (p = 1.000). Only 3 patients required on-demand sedation (intravenous midazolam plus fentanyl): 2 patients (2.9%) in the water group and 1 patient (1.4%) in the air group (p = 0.620), the same patient that reported maximum pain level in this group. The proportion of patients that considered the procedure to be easier than expected was significantly higher in the water group, 68.6% (n = 48), as compared to the air group, 36.6% (n = 26), p < 0.001. Only 2 patients, 1 in each group, showed no willingness to repeat the procedure in the future, under the same circumstances.

Procedural Data

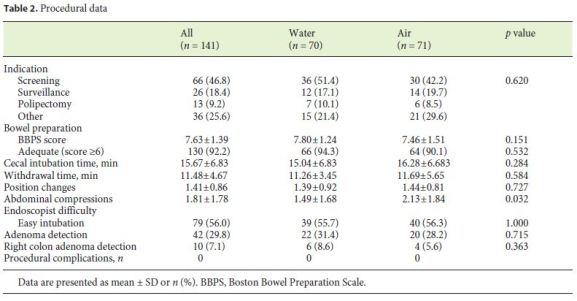

Procedural data are summarized in Table 2. Cecal intubation rate was comparable between the two groups: 93.8% for the air group and 92.6% for the water group (p = 0.712). Of the 6 failed cecal intubations in the water group, only 2 procedures were completed with AI.

There were no significant differences between the two groups regarding indications for the procedure, quality of bowel preparation, cecal intubation time and withdrawal time and number of position changes. Only the number of abdominal compressions was significantly different, showing that WE could decrease the average number of compressions during colonoscopy (1.49 ± 1.68 vs. 2.13 ± 1.84, p = 0.032). The proportion of procedures classified by the endoscopist as easy intubation was not statistically different between the two groups.

The adenoma detection rate, including right colon detection rate, was slightly higher in the water group, but the differences did not reach statistical significance. There were no immediate or late reported complications in either group. In the water group, there was a positive moderate correlation between the reported level of pain and cecal intubation time (r = 0.432; p < 0.001). Also, a cecal intubation classified by the endoscopist as difficult or very difficult was associated with a higher level of pain (4.48 vs. 2.33, p < 0.001).

Discussion

In this head-to-head comparison of WE and AI in patients undergoing total colonoscopy without sedation, the WE method significantly decreased the maximum level of pain reported by the patients, with a significantly higher proportion of patients reporting a painless procedure.

Indeed, the cause of visceral abdominal pain is multifactorial, depending not only on the stretch of the mesenteric attachments, but also on the individuals susceptibility to the perception of pain, the pressure of gas distention and the patients anticipation of a high pain level [17, 18].

WE presents itself as a promising technique as it simultaneously lubricates the scope-mucosa interface, smoothes bends and flexures, and avoids gas-induced distention and elongation [7]. This explains the lower level of pain reported by patients, as well the perception that the examination was easier than expected.

Furthermore, the positive effect of the WE does not impair the key performance measures for lower gastrointestinal endoscopy advocated by the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) and United European Gastroenterology (UEG) [19]: the rate of adequate bowel preparation, cecal intubation rate, adenoma detection rate, and complication rate in this study accomplished the proposed thresholds.

Several randomized controlled trials reported that WE significantly increased bowel cleanliness, compared to AI, when full dose or split-dose was used [9]. In the simultaneous infusion and water suction process, the jet stream of water is more effective in creating turbulence and removing residual feces and debris adherent to the colonic mucosa. In contrast, when AI is used, the colon is more stretched and the water jet reaches a smaller colonic area with less turbulence, decreasing the salvage cleaning provided by water instillation [7].

Additionally, it has also been hypothesized that a larger volume of instilled water could be the main reason for the salvage cleansing effect of WE, with a recent randomized trial supporting this hypothesis [7]. This trial reported that the center in which a lower insertion volume of water was used in the WE method, the bowel cleanliness was not improved compared to the AI method. Quantification of the volume of infused water during the examination, probably the main driver for a better colon cleansing, was not performed in our study. Thus, the salvage cleansing effect of the WE method, subject to interoperator variability, could not be addressed in our study. The evidence that there were no significant differences related to bowel preparation between the two groups does not allow us to draw conclusions on the effect of WE on the optimization of colon cleanliness, at the risk of corresponding to skewed information.

Moreover, recent published data also suggest that WE is superior to WI and AI in increasing the adenoma detection rate [7, 20]. This might be explained by a better colon cleansing, easier recognition of polyps with the floating effect of water, better visualization of flat lesions as water does not fully distend colonic wall as gas insufflation does, and by improved attention of the operator during the withdrawal phase, with fewer distractions due to the washing and cleaning process [9].

In our study, the WE method did not achieve the highest cleanliness scores; consequently, our interpretation concerning adenoma detection rate could also be compromised. The water group showed a slightly higher adenoma detection rate, although it did not reach statistical significance.

Our study is underpowered to detect differences concerning bowel cleanliness and adenoma detection rate. Therefore, a new study with a larger sample size, standard split-dose bowel preparation, quantification of the infused water during insertion and withdrawal phases, and adenoma detection rate as a primary endpoint would be of great convenience to our Center, in order to determine the benefit of the WE method in these key performance measures.

In this study, patient experience has not been self-reported using a validated scale, as proposed by ESGE, but rather evaluated by taking into account 2 questions regarding the perceived difficulty and willingness to repeat the examination, showing that patients in the water group considered the procedure to be easier than expected in a significantly higher proportion.

Other procedure measures, like the cecal intubation time and withdrawal time, that could potentially be increased in the water group as it was a new technique in which operators had less experience, showed no differences when compared to the air group. Indeed, the available literature states that the learning process of the water method in a community setting is feasible, with a learning curve easily achievable by an experienced endoscopist [14, 21]. For trainee endoscopists, there is also evidence of an easy and fast learning curve, being rated by them as an easier technique to learn, showing a trend toward superiority in reaching the cecum [15].

In this study, the procedures were performed mostly by trainee endoscopists, with a senior:trainee ratio of 1: 4. However, all of the trainees had sufficient experience in unsedated colonoscopy according to The European Section and Board of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. Apart from that, all the operators had performed at least 50 WE colonoscopies before accepting to participate in the study, the threshold reported in the literature to perform the technique adequately, even in the absence of an onsite trainer [14].

In our study, we routinely instilled room-temperature water (20–24 ° C), despite the fact that most of the trials comparing WE and AI used warm water [7, 22, 23], what could potentially contribute to less colonic spasm. However, there is no evidence of significant differences in major procedure outcomes when comparing warm and room-temperature water [24], and so we did not consider this aspect as a limitation of the study.

There are some limitations to this study. First, the endoscopists participating in the study had different levels of experience in colonoscopy, which could have led to different levels of pain, as well as to asymmetries in other performance measures. An endpoint analysis for each operator would have allowed us to correlate the level of pain with the endoscopists experience. Second, despite the fact that patients were blinded to the technique used, the nature of the method did not allow blinding of the endoscopist and assisting nurse. Third, it was a single-center study with only 5 endoscopists included.

This is the first study on water-assisted colonoscopy performed in Portugal. A multicenter trial, with more patients and more endoscopists, would probably have allowed us to overcome some of the limitations and to draw conclusions concerning bowel cleanliness and adenoma detection rate, and to determine the predictive factors of painless colonoscopy in each group.

Conclusions

Our main goal was to analyze the impact of the WE method on patients perceived pain during sedation-free colonoscopy as well as its impact on other colonoscopy performance measures in a center without previous experience in this technique.

The results obtained in this study corroborate the promising role of WE in the community setting, translating into a better clinical practice and contributing to a greater population adherence to colonoscopy. Despite recent evidence supporting the benefits of WE, there is still some reluctance among endoscopists regarding the true benefits of this method.

References

1 de Groen PC: Editorial: polyps, pain, and propofol: is water exchange the panacea for all? Am J Gastroenterol 2017;112:578–580. [ Links ]

2 Trevisani L, Zelante A, Sartori S: Colonoscopy, pain and fears: is it an indissoluble trinomial? World J Gastrointest Endosc 2014;6:227–233. [ Links ]

3 Terruzzi V, Paggi S, Amato A, Radaelli F: Unsedated colonoscopy: a neverending story. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2012;4:137–141. [ Links ]

4 Wernli KJ, Brenner AT, Rutter CM, Inadomi JM: Risks associated with anesthesia services during colonoscopy. Gastroenterology 2016;150:888–894; quiz e18. [ Links ]

5 Ishaq S, Neumann H: Water assisted colonoscopy: a promising new technique. Dig Liver Dis 2016;48:569–570. [ Links ]

6 Anderson JC, Pohl H: Water and carbon dioxide – turning back the clock to unsedated colonoscopy. Endoscopy 2015;47:186–187. [ Links ]

7 Cadoni S, Falt P, Rondonotti E, et al: Water exchange for screening colonoscopy increases adenoma detection rate: a multicenter, double-blinded, randomized controlled trial. Endoscopy DOI: 10.1055/s-0043-101229. [ Links ]

8 Falchuk ZM, Griffin PH: A technique to facilitate colonoscopy in areas of severe diverticular disease. N Engl J Med 1984;310:598. [ Links ]

9 Cadoni S, Leung FW: Water-assisted colonoscopy. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol 2017;15:135–154. [ Links ]

10 Maple JT, Banerjee S, Barth BA, et al: Methods of luminal distention for colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc 2013;77:519–525. [ Links ]

11 Jun WU, Bing HU: Comparative effectiveness of water infusion vs air insufflation in colonoscopy: a meta-analysis. Colorectal Dis 2013;15:404–409. [ Links ]

12 Lin S, Zhu W, Xiao K, et al: Water intubation method can reduce patients pain and sedation rate in colonoscopy: a meta-analysis. Dig Endosc 2013;25:231–240. [ Links ]

13 Rabenstein T, Radaelli F, Zolk O: Warm water infusion colonoscopy: a review and meta-analysis. Endoscopy 2012;44:940–951. [ Links ]

14 Ramirez FC, Leung FW: The water method for aiding colonoscope insertion: the learning curve of an experienced colonoscopist. J Interv Gastroenterol 2011;1:97–101. [ Links ]

15 Ngo C, Leung JW, Mann SK, et al: Interim report of a randomized cross-over study comparing clinical performance of novice trainee endoscopists using conventional air insufflation versus warm water infusion colonoscopy. J Interv Gastroenterol 2012;2:135–139. [ Links ]

16 Leung FW: Water exchange may be superior to water immersion for colonoscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011;9:1012–1014. [ Links ]

17 Oh SY, Sohn C Il, Sung IK, et al: Factors affecting the technical difficulty of colonoscopy. Hepatogastroenterology 2007;54:1403– 1406. [ Links ]

18 Lai X-Y, Tang X-W, Huang S-L, et al: Risk factors of pain during colonoscopic examination (in Chinese). Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao 2016;37:482–487. [ Links ]

19 Kaminski MF, Thomas-Gibson S, Bugajski M, et al: Performance measures for lower gastrointestinal endoscopy: a European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Quality Improvement Initiative. Endoscopy 2017;49:378–397. [ Links ]

20 Hsieh Y-H, Tseng C-W, Hu C-T, Koo M, Leung FW: Prospective multicenter randomized controlled trial comparing adenoma detection rate in colonoscopy using water exchange, water immersion, and air insufflation. Gastrointest Endosc DOI: 10.1016/j.gie.2016.12.005. [ Links ]

21 Fischer LS, Lumsden A, Leung FW: Water exchange method for colonoscopy: learning curve of an experienced colonoscopist in a U.S. community practice setting. J Interv Gastroenterol 2012;2:128–132. [ Links ]

22 Hsieh Y-H, Koo M, Leung FW: A patient-blinded randomized, controlled trial comparing air insufflation, water immersion, and water exchange during minimally sedated colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol 2014;109:1390–1400. [ Links ]

23 Cadoni S, Falt P, Gallittu P, et al: Water exchange is the least painful colonoscope insertion technique and increases completion of unsedated colonoscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;13:1972–1973. [ Links ]

24 Falt P, Smajstrla V, Fojtik P, Tvrdik J, Urban O: Cool water vs warm water immersion for minimal sedation colonoscopy: a double-blind randomized trial. Colorectal Dis 2013;15:e612–e617. [ Links ]

Statement of Ethics

Protection of Human and Animal Subjects

The authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of Data

The authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to Privacy and Informed Consent

The authors have obtained the written informed consent of the patients or subjects mentioned in the article. The corresponding author is in possession of this document.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

* Corresponding author.

Dr. Richard Azevedo

Department of Gastroenterology, Amato Lusitano Hospital

Avenida Pedro Álvares Cabral

PT–6000-085 Castelo Branco (Portugal)

E-Mail richardazevedo13@gmail.com

Received: August 1, 2017; Accepted after revision: October 9, 2017

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Department nurses for their important contribution to this study.

Author Contributions

Cátia Leitão was responsible for the study design. Cátia Leitão, Richard Azevedo, Helena Ribeiro, João Pinto and António Banhudo collected data for the study. Richard Azevedo and Flávio Pereira were responsible for statistical analysis. Richard Azevedo and Cátia Leitão wrote the manuscript. Ana Caldeira and António Banhudo revised and approved the final manuscript.