Introduction

Pancreatic cancer and chronic pancreatitis are commonly associated with intense and often refractory pain [1]. Pain usually occurs in the occult stage of the disease and gradually worsens as the disease progresses [2]. Moreover, cancer pain markedly reduces the quality of life and is considered a prognostic factor for survival.

Therefore, palliative pain control is crucial in the context of advanced pancreatic cancer [3, 4]. Non-narcotic medical therapies are often inadequate, and opioids commonly induce nausea, constipation, and other side effects [5]. If patients have refractory pain or cannot tolerate increasing amounts of opioid medications, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided celiac plexus block (CPB) and neurolysis (CPN) may play an important role [4]. CPB is a temporary treatment and most commonly refers to the injection of a steroid and a long-acting local anaesthetic into the celiac plexus. In contrast, CPN generally refers to injection of alcohol or phenol, agents that induce ablation of the nerve fibres, conducting to a more permanent effect [6].

The anatomical location of celiac plexus, near the origin of the celiac trunk and superior mesenteric artery, is easily accessed by EUS. This approach, providing a near-field and real-time visualization, is preferable to the percutaneous one, and is considered nowadays, the safer, faster, and easier technique for celiac plexus interventions [7].

In this chapter, the Portuguese Group for Ultrasound in Gastroenterology (GRUPUGE) presents a perspective of the potential role of EUS-guided celiac plexus interventions, addressing the selection criteria and technical issues of different techniques and analysing emerging data on their efficacy and safety. A systematic literature search was performed until January 2020 using PubMed, Medline, Scopus, and Google, using the keywords “chronic pancreatitis,” “pancreatic cancer,” “pancreatic pain,” “endoscopic ultrasound,” “celiac plexus block,” “celiac plexus neurolysis,” and “celiac ganglia.” Prospective/comparative studies and international consensus statements/ management guidelines were preferred. The final manuscript was revised and approved by all members of the Governing Board of the GRUPUGE.

Indications and Contraindications

CPB is indicated for management of pain associated with chronic pancreatitis. CPN is mostly indicated in patients with pancreatic cancer [4]. A recent consensus statement recommends against EUS-CPN for the treatment of chronic pancreatitis pain [8]. Given how rarely EUS-CPN is used in chronic pancreatitis and the relatively high proportion of reported significant complications, EUS-CPN for chronic pancreatitis pain may (for unknown reasons) be riskier than EUS-CPN for malignancy.

CPN should be considered when pancreatic cancer patients have intolerable adverse effects to opioid therapy such as drowsiness, somnolence, confusion, delirium, dry mouth, anorexia, constipation, nausea, and vomiting, or if an analgesic ceiling is achieved because of neurotoxicity [9].

The timing of the celiac intervention relative to pain onset appears to be an important predictor of pain response in patients with pancreatic cancer. Early pancreatic cancer pain appears to derive mainly from the celiac plexus involvement, while pain during the terminal stages of the disease may also involve other visceral and somatic nerves [10]. Thus, CPN performed soon after the onset of pain from pancreatic cancer may increase the rate of response.

However, the potential benefit of early EUS-CPN in the quality of life of these patients is still undefined. Current guidelines for the management of pancreatic cancer do not state specific recommendations regarding the timing for EUS-CPN in the treatment of cancer-associated pain [11]. The ESMO guidelines state that EUS-CPN should be carried out in the presence of resistant pain and only if the clinical condition of the patient is not poor [12]. A single randomized, doubleblind, controlled trial pointed out to a potential benefit of early EUS-CPN, performed at the time of the diagnosis of unresectable pancreatic cancer, in patients with abdominal pain at presentation [13]. According to a recent consensus statement, when on-site cytopathology is available, patients with painful inoperable pancreas cancer should undergo EUS-CPN at the time of diagnosis [8]. Despite this, in current clinical practice, EUSCPN is commonly considered late after the diagnosis of pancreatic cancer, being conventionally reserved for refractory pain after failure of a step-wise analgesic ladder strategy or when side effects of such therapy become difficult to control.

Potential contraindications are thought to include impaired coagulation (international normalized ratio [INR] > 1.5 and/or platelets < 50,000/mm3), inadequate visualization or access to the region of the celiac artery (CA) take-off [14], modified anatomy from prior surgery, congenital abnormalities, or bowel obstruction.

Anatomy

Although the terms “celiac plexus” and “splanchnic nerves” are often used interchangeably, they are anatomically distinct structures [15, 16]. The splanchnic nerves are located above and posterior to the diaphragm and anterior most often to the 12th thoracic vertebra. The celiac plexus is located below and anterior to the diaphragm and surrounds the origin of the celiac trunk. Celiac plexus is a network of ganglia that relays preganglionic sympathetic and parasympathetic efferent fibres and visceral sensory afferent fibres to the upper abdominal viscera. The celiac plexus transmits the sensation of pain from the pancreas. The visceral sensory afferent fibres transmit nociceptive impulses from the liver, gallbladder, pancreas, spleen, adrenal glands, kidneys, distal oesophagus, and bowel to the level of the distal transverse colon. Located in the retroperitoneum just inferior to the celiac trunk and along the bilateral anterolateral aspects of the aorta, between the levels of the T12-L1 disc space and L2, the celiac plexus can easily be reached by EUS [6].

Procedural Description

Pretreatment Procedure

The procedure usually is performed under sedation on an outpatient basis. Due to its invasiveness, a platelet count and coagulation profile should be assessed before the procedure [17]. In addition, antiplatelet and anticoagulation therapies must be reviewed, and appropriate modification or cessation of these agents is advised given the risk of bleeding [18]. Patients are initially hydrated with 500-1,000 mL normal saline to minimize the risk of hypotension usually associated with CPN. Throughout the procedure, patients are continuously monitored by na automated non-invasive blood pressure device and pulse oximeter [14].

Taking into account the infectious adverse events related to CPB, usually related to the use of a steroid agent, some authors suggested that prophylactic antibiotics should be considered, especially in patients under acid suppression therapy [19]. For the choice of antibiotic regimen, local guidelines should be followed.

General Endoscopic Technique

The technique for EUS-guided CPN and CPB is identical, the main difference being the injected substances. A 22- or 19-gauge EUS fine-needle aspiration needle is usually used. If a specially designed 20-gauge “spray needle” with multiple side holes is available, it could be used to spread the desired agent through a larger area [20].

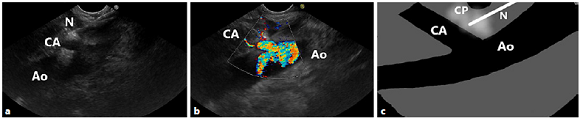

The endosonographic anatomic landmark of the celiac ganglia is typically located at the posterior gastric wall, just below the gastroesophageal junction, approximately 40 cm from the incisors. By EUS, the ganglia may be seen as two small (2-3 mm) elongated hypoechoic structures with hyperechoic central foci, anterolateral to the aorta, adjacent to the celiac trunk, just distal to the take-off of the CA from the aorta (Fig. 1) [21-23]. For a better individualization of vascular structures, a Doppler study is usually performed.

Fig. 1 Relevant anatomy for the CPN and CPB procedure. EUS image (a) with colour Doppler (b), and diagrammatic scheme (c) from the lesser curvature of the stomach, showing the celiac plexus located anterior to the aorta. Note the needle at the base of the celiac artery. Ao, aorta; CA, celiac artery; CP, celiac plexus; N, needle.

The needle tip is placed slightly anterior and cephalad to the origin of the CA or directly into the ganglia if these can be identified as distinct structures. A syringe containing the injectate is attached to the needle, and aspiration is performed to rule out inadvertent blood vessel penetration prior to any injection.

Celiac Plexus Neurolysis

EUS-guided techniques for performing celiac neurolysis may be categorized as those which involve diffuse injection into the celiac plexus (CPN) and those in which the celiac ganglia are directly targeted (celiac ganglia neurolysis, CGN).

Two approaches are currently used when performing EUS-CPN [4]. The classic approach, known as the central technique, involves injection of the agent at the base of the CA. In the second approach, the bilateral technique, the neurolytic agent is injected on both sides of the CA.

There are limited and conflicting data regarding the efficacy of single versus bilateral injection [24]. Generally, a mixture of 30% by volume of 0.25% bupivacaine with 70% by volume of 98% dehydrated alcohol is used. Data to guide the optimal injectate type, volume, and mixing ratio are still lacking. The total volume of solution injected is usually 10-20 mL and before withdrawing the needle, a small amount of normal saline solution (3 mL) should be flushed to fully clear the whole medication [25], and to avoid a possible caustic effect of the alcohol on the gastric mucosa.

Celiac Plexus Block

The technique for CBP is essentially the same as for CPN. Generally, in a unilateral approach, 20 mL of 0.25% bupivacaine followed by 40-80 mg of triamcinolone are injected. If a bilateral approach is chosen, the dose is divided in two and injected in both sides of the celiac plexus [6].

Alternative Modalities

Celiac Ganglia Neurolysis

Research has focused on the ability of EUS injection therapy to target the celiac ganglia specifically (CGN). A recent multicentre randomized trial [26] showed a superiority of direct CGN over CPN in pain response rate on the 7th day after the procedure. Although these studies demonstrate significantly better short-term pain relief with the direct ganglia injection approach, data referring to the long-term efficacy is still lacking, and the procedural technique is yet to be standardized. Although some authors did not show significant differences in pain relief between CGN and bilateral or broad plexus EUS-CPN [8], according to a Brazilian consensus statement, in patients with clearly visible ganglia, CGN appears to have better efficacy and should be preferable to CPN [27].

Broad Plexus Neurolysis

An alternative approach that has been described for patients with advanced abdominal cancer involves EUSguided broad plexus neurolysis (BPN), in which the injection is performed at the level of the superior mesenteric artery (generally with a 25-gauge needle), resulting in a broader distribution of neurolysis. In one trial with 67 patients assigned to either conventional CPN or BPN, patients in the BPN group had a significantly better shortand long-term pain relief [28].

Radiofrequency Ablation

Recently, radiofrequency ablation (RFA) has been used for ablation of celiac ganglia in patients with pancreatic cancer [29, 30]. According to the recent literature, RFA has been developed mainly for the treatment of locally advanced pancreatic cancer. For this reason, it is not considered an alternative in current clinical practice in the treatment of pancreatic pain.

A recently published study [30] has found that EUSRFA provided better pain relief without any difference in the rate of adverse events. Importantly, 21% of patients with persistent pain after CPN could be successfully managed with RFA. The proposed advantages of EUS-RFA over EUS-CPN using alcohol include a more predictable area of necrosis and immediate symptom relief. However, the data are limited and the ideal settings of RFA have yet to be determined.

Postprocedural Follow-Up

After the procedure, the patient’s vital signs should be monitored (temperature, blood pressure, and heart rate) for at least 2 h. Prior to discharge, blood pressure should be checked both in supine and erect positions to assess postural hypotension [6].

Adverse Events

Adverse events related to EUS-guided CPN and CPB occur in up to 30% of cases, most commonly diarrhoea (7%), increase in abdominal pain (2-4%), and hypotension (4%). All symptoms are usually mild and self-limiting [31-33]. Serious adverse events related to EUSguided CPN (0.2%) and CPB (0.6%) were reported and include bleeding, retroperitoneal abscess, abdominal ischemia, permanent paralysis (including diaphragmatic paralysis), pneumothorax, peritonitis, infections, liver or spleen infarction, and death [33, 34]. Possible mechanisms of injury include diffusion of neurolytic agent adjacent to the CA, resulting in arterial vasospasm reflecting the sclerosing effect of absolute ethanol and arterial embolization following injection [25].

Due to some serious adverse events that have been reported with EUS-guided CPN, it should not be used for the treatment of chronic pancreatitis pain.

Infectious complications of EUS-CPB are uncommon. In a series of 90 patients, only 1 developed an infectious complication (a peripancreatic abscess), which resolved with a 2-week course of antibiotics [35]. The authors speculated that there may have been a predisposition to infection because the patient was taking a proton pump inhibitor at the time of the procedure and may have had gastroduodenal colonization with bacteria. The bactericidal nature of ethanol (used in CPN) appears to minimize this risk for infection.

Efficacy

Studies have shown that there is variability in the efficacy regarding pain relief associated with CPB and CPN. Although CPB and CPN are considered safe procedures, the long-term efficacy of CPB and CPN has been limited in terms of duration of pain relief, and the effects on quality of life are controversial [6]. A meta-analysis of EUSguided CPB and CPN reported response rates of 59% in chronic pancreatitis and 80% in pancreatic cancer; however, most of these patients continued to take analgesic medications [36].

The average length of relief obtained with CPB is approximately 3 months, and this procedure should, therefore, be considered a temporizing measure [37].

The early use of CPN in patients with inoperable cancer may improve pain relief compared with conventional pain management. In a randomized control trial, 96 patients were randomly assigned to early EUS-CPN or conventional pain management, if EUS and EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration cytology confirmed inoperable adenocarcinoma [13]. Pain scores, morphine equivalent consumption, and quality of life scores were assessed at 1 and 3 months. At 3 months, patients treated with CPN had significantly greater pain relief, with a trend toward lower morphine consumption, so the authors concluded that EUS-CPN can be considered in such patients at the time of diagnostic and staging EUS. Nevertheless, no difference between the groups was seen in quality of life scores or survival.

Key Points

− Pain is common and frequently disabling in patients with pancreatic cancer and chronic pancreatitis.

− EUS-guided celiac plexus interventions, in combination with conventional analgesia, may be useful for pain management in patients with pancreatic disease (malignant or chronic pancreatitis).

− EUS-CPB is a transient interruption of the plexus by local anaesthetic, while EUS-CPN leads to a prolonged interruption of the transmission of pain from the celiac plexus by the use of chemical agents such as alcohol or phenol.

− Significant pain control is achieved with EUS-CPN in the setting of pancreatic cancer (80%). More modest results are seen in patients with abdominal pain secondary to chronic pancreatitis after EUS-CPB (59%). Effects on quality of life are controversial.

− The safety profile of EUS-guided CPN and CPB is favourable. Procedure-related complications include transient pain exacerbation, transient hypotension, or transient diarrhoea. Although most complications are not serious, major adverse events (nearly 0.2%), such as retroperitoneal bleeding, abscess, and ischemic complications, occasionally occur. Due to some serious adverse events that have been reported with EUS-guided CPN, it should not be use for the treatment of chronic pancreatitis pain.

− CPN should not be considered when surgery may still be an option for patient treatment.

− BPN and RFA are promising alternative techniques, but further studies are needed for its validation in clinical use.