Introduction

Increased prevalence of antimicrobial-resistant microorganisms is becoming a global public health problem, and one of the most important medical challenges faced by the worldwide infectious disease community [1]. In this setting, there has been a growing interest in fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) as a way to manipulate gut microbiota. FMT is defined as a procedure where feces from a healthy donor are infused in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract of a recipient patient to treat a disease associated with alteration of the gut microbiota, in order to restore the healthy microbial flora [2]. Currently, recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection is the single formal indication where FMT has an undeniable role with a cure rate of 93.8% after one or two duodenal infusions of donor feces [3]. More recently, several published studies also reported benefit in patients with multidrug-resistant (MDR) bacteria. Bilinski et al. [4] showed that not only FMT was safe in immunosuppressed patients with hematological diseases, but it also eradicated MDR bacteria from the GI tract of this particularly vulnerable population. A Dutch group [5] treated 15 patients carrying extended spectrum beta lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae (ESBL-EB) with FMT with very encouraging results. Twenty percent (n = 3) of the patients were ESBLnegative at 1, 2, and 4 weeks after the first transplant, while 40% (n = 6) were negative after the second transplant. A recently published systematic review addressed the use of FMT for decolonization and prevention of MDR infection [6]. Twenty-one studies including 192 patients were analyzed. The population was heterogenous and included particularly susceptible groups of patients (hematological disorders, cancer, and post-solid organ transplant) colonized with MRD bacteria - carbapenemresistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE), vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE), ESBL-EB, and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). In most studies, donors were unrelated, and frozen stools were used. Upper GI endoscopy was the most frequently used route of FMT administration, and eradication rates varied between 37.5 and 87.5%. Follow-up ranged from 14 to 1,200 days, and no serious adverse events were reported.

We present a case of a patient with 30 hospital admissions during a 6-year period for repeated episodes of cholangitis. The patient had undergone multiple endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatographies (ERCPs) with biliary sphincterotomies and two papillary balloon dilations. Due to this desperate scenario in an elderly patient infected with MDR bacteria only sensitive to meropenem and colystin, we tried FMT with the purpose of reprograming gut microbiota and eventually reducing the number of MDR bacteremias with probable origin on the gut.

Case Report and Case Presentation

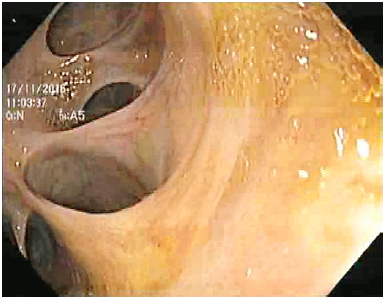

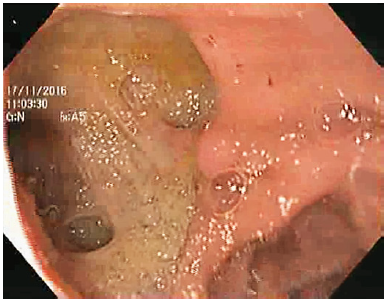

We present the case of an 87-year-old male with a history of atrial fibrillation, hypertensive heart disease, stage 3 chronic kidney disease, and undetermined monoclonal gammopathy, medicated with valsartan, bisoprolol, and apixaban. He was a nonsmoker, had no known allergies, and his family history was irrelevant. He underwent cholecystectomy in 1992 for complicated cholelithiasis. After surgery, he still had recurrent residual choledocholithiasis often complicated with acute cholangitis, leading to approximately six hospitalizations between 1993 and 2012. During this period, he underwent multiple ERCPs, which showed a dilated common bile duct with poor biliary drainage and multiple gallstones, which were removed at each instance. Since he was first admitted to our hospital in 2012, he had 12 episodes of acute cholangitis requiring hospital admission between 2012 and 2014. During these 2 years, 8 ERCPs were performed with enlargement of previous sphincterotomy and two papillary balloon dilations up to 10 mm. Because the recurrent episodes of cholangitis remained despite successive ERCPs with stone removal, biliary atony was identified as the main problem, but we also hypothesized that biliary drainage impairment could also be present. Because of this, he underwent a side-to-side choledochoduodenostomy in May 2014. Nevertheless, after surgery, recurrent episodes of acute ascending cholangitis kept on occurring at an increased frequency, despite no evidence of biliary lithiasis or anastomotic stenosis. The patient presented with fever, chills and asthenia, normal liver function tests (after surgery), and bacteremia was documented in most instances. Biliary gallstones, anastomotic stenosis, and other infectious diseases were excluded. Upper GI endoscopy showed a patent biliodigestive anastomosis with stump dilation, making progression through biliary ducts feasible with a 12-mm therapeutic endoscope (Fig. 1, 2). The patient underwent a hepatobiliary scintigraphy, which revealed a biliary drainage delay with intrahepatic and

choledochal biliary stasis, but with complete drainage by the end of the study. Sump syndrome was excluded as the magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography and ERCP did not show any content at the anastomosis or the common bile duct between the anastomosis and the ampulla of Vater. After discussion with the surgical team, a surgical anastomotic reconstruction was not considered an option due to the patient’s advanced age and comorbidities. He had a mean of 3-5 hospitalizations per year, with a total of 30 hospital admissions between 2012 and 2018, corresponding to 353 days in hospital. During these years, several therapeutic strategies, such as prophylactic antibiotic therapy (including rifaximin), probiotics, prokinetics, and ursodeoxycholic acid were unsuccessfully attempted. In the beginning of 2018, there was a worsening of these cholangitis episodes with six additional hospitalizations during the first 8 months, the last ones at 1- or 2-week intervals, and a need for a progressive escalation of antibiotics due to isolation of MDR bacteria in blood cultures. Resistant microorganisms isolated throughout 2018 were Klebsiella pneumoniae ESBL, Escherichia coli ESBL, and K. pneumoniae CRE requiring antibiotic therapy with carbapenems, amikacin and colistin, amongst others. During the last hospitalization before FMT, an Enterobacter aerogenes only susceptible to amikacin and meropenem was grown in blood cultures. After case discussion with the Infection Control and Microbiology Committee, an FMT was proposed, aiming at manipulating gut microbiota and eventually decreasing MDR bacteria. In September 2018, we performed an FMT via colonoscopy using fresh feces (500 mL) from a related healthy donor (Fig. 3). The donor as the patient’s niece who volunteered to donate the fecal sample. She was healthy and had infrequent contact with the patient.

Fig. 2 Upper GI endoscopy showing a biliodigestive anastomosis with stump dilation, making progression through the biliary ducts with a therapeutic endoscope possible.

Fig. 3 Stages of fecal material processing in a level 2 biosafety unit. The stool sample is weighed (a), mixed with saline solution (b), homogenized in a vortex (c), and then filtered through a gauze to remove solid debris (d, e). Finally, the sample is stored (f) and then transferred to the endoscopy unit.

Routine blood tests were normal, and using serology she was screened for cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr, hepatitis A, B, C and E, human immunodeficiency virus 1 and 2, and Treponema pallidum; stool tests including C. difficile toxin, Giardia lamblia, norovirus, rotavirus, and fecal Helicobacter pylori antigen were performed. Fecal cultures for Salmonella spp., Shigella spp., Campylobacter spp., E. coli OH 157 H7, Yersinia spp., MDR -ESBL-EB, CRE, VRE and MRSA - were also excluded. Fecal occult blood test was performed as well. The patient’s niece was 35 years old and had never been submitted to a colonoscopy before. After the first FMT, the patient still had 3 more hospitalizations for cholangitis, the last 2 weeks apart, but MDR bacteria were no longer isolated from blood cultures. On the first admission, a C. freundii resistant only to amoxicillin and clavulanic acid was isolated. The patient received piperacillin and tazobactam at all three admissions, with good responses. Considering the apparent change in the microbial resistance profile, and based on existing experience with C. difficile infection in which a second FMT may be required, we performed a second FMT in January 2019, this time via the upper GI route using the same donor. A total of 100 mL of fecal material was infused 30 cm below the biliodigestive anastomosis. After the second FMT, the patient remained asymptomatic and without hospitalizations for 4 months. At the end of April 2019, the patient relapsed with 3 more hospitalizations but with negative blood cultures. He was treated with piperacillin and tazobactam for 1 week in all instances. This relapse led us to repeat FMT via upper GI endoscopy with the same donor in July 2019. Four months after the last FMT and at the time of writing this paper, the patient was well and had no further episodes of ascending cholangitis.

Discussion and Conclusion

We present the case of a patient with recurrent episodes of ascending cholangitis after cholecystectomy performed 20 years before. ERCP showed a dilated common bile duct with poor biliary drainage and multiple gallstones. Eight ERCPs with sphincterotomy and papillary balloon dilations were performed on multiple occasions. Biliary atony was obviously the main problem, but we also hypothesized that biliary drainage could also play a role and a choledocoduodenostomy was performed. Unfortunately, the latter was not effective, and recurrent ascending cholangitis with bacteremias kept on occurring. During the past 6 years, the patient had been hospitalized 30 times, lately with 2 weeks between each admission, with the need for progressive antibiotic escalation due to increased frequency of MDR bacteria isolation in blood cultures. Before FMT, an E. aerogenes only susceptible to amikacin and meropenem was isolated from blood cultures. Because surgical reconstruction was not considered an option, FMT was proposed with the aim of modulating gut microbiota and eventually decreasing MDR bacteria. We performed the first FMT via colonoscopy for safety reasons, [7] with fresh feces from a related donor who was submitted to extensive screening. After the first FMT, the patient was still admitted with fever thrice, but we noticed a change in his microbial resistance profile. On the first hospitalization after FMT, a Citrobacter freundii was isolated from blood cultures, resistant only to amoxicillin and clavulanic acid. Due to the existing experience with Clostridioides difficile infection in which a second FMT is sometimes required [3], we performed a second FMT, this time using the upper GI route. After this, the patient remained asymptomatic and without hospitalizations for 4 months. The upper route was used since previous studies showed its efficacy [7], and we were aiming at changing gut microbiota mainly in the upper GI tract. This also avoided a bowel preparation in this elderly and fragile patient. After these 4 months, he relapsed again, but it is worth noting that at this point no agent was isolated in blood cultures, and he was treated with piperacillin and tazobactam for 1 week. Together with the patient and his relatives, we decided to repeat FMT using the upper GI route again. At 4 months of follow-up, he is asymptomatic and without further readmissions. All FMT procedures were performed without complications.

In this patient, gut colonization with MDR bacteria was probably a consequence of multiple broad-spectrum antibiotic courses needed to treat multiple episodes of acute cholangitis for at least 6 years. The goal of FMT in this patient was to reprogram gut microbiota, using healthy donor feces, and consequently to reduce the number of MDR bacteremia episodes with a possible gut/biliary source. In this case, it is likely that FMT not only changed gut microorganisms’ resistance profile but also increased the remission period, as the patient remained symptom free and without further hospitalizations for 4 months after the second and third FMTs. It is worth noting that before the first FMT, the patient presented with bacteremias requiring hospital admission every 1-2 weeks, and MDR bacteria were systematically isolated from blood cultures. The upper GI route may have been more efficient since the biliodigestive anastomosis was probably the source of ascending cholangitis and consequent bacteremia. Fecal material administration was performed distal to the surgical anastomosis (30 cm) to avoid direct biliary bacterial instillation. We can hypothesize that patient relapses after FMT are related to gut microbiota returning to its baseline after the procedure. Former gut microbiota studies show that FMT-induced microbiota alterations can last anywhere from a few days to a few years after transfer [8-10].

Despite the relative success of this case, it is important to acknowledge that pathogenic bacteria can also be introduced in the recipient, as demonstrated in the two first case reports [11] of drug-resistant E. coli bacteremia acquired after FMT, underlining the importance of a rigorous donor screening and traceability of the transplanted material.

The present case illustrates that FMT may be effective in decreasing the frequency of MDR systemic infections, even in elderly patients with several comorbidities. In the future, with growing evidence supporting the use of FMT in MDR elimination, we might consider performing FMT “on-demand” in selected patients as a decolonization strategy.