Introduction

Acute liver failure (ALF) is a rare syndrome, representing 8% of all liver transplants in Europe [1]. Multiple conditions may evolve to ALF, and establishing aetiology has prognostic and therapeutic importance [2]. Budd-Chiari syndrome (BCS) is a rare disease, with the recent estimates of incidence and prevalence widely varying depending on the studies [3]. In Europe, BCS prevalence is estimated at 1.4-2 per million inhabitants [4, 5] and, particularly in France, the incidence is estimated at 2.17 per million habitants, reflecting the rarity of this syndrome [3]. BCS refers to the obstruction of hepatic veins or the terminal inferior vena cava, and has a wide spectrum of presentation, from asymptomatic to ALF [6]. ALF is, however, a rare complication [7]. In Western countries, multiple risk factors have been identified, from the intake of oral contraceptives, underlying prothrombotic conditions, and, most commonly, myeloproliferative disorders, with most of the patients having more than one risk factor [3, 6]. Darwish Murad et al. [8] identified the presence of one risk factor in 84% of the patients and two ormore risk factors in 46%. Besides myeloproliferative disorders, which are commonly associated with BCS [3], other haematological neoplasms are quite rare and only published as case reports [9-11]. As malignancy is a formal and absolute contraindication for liver transplantation (LT) in the acute setting, its exclusion in the workup diagnosis of ALF is mandatory [2].

Case Report

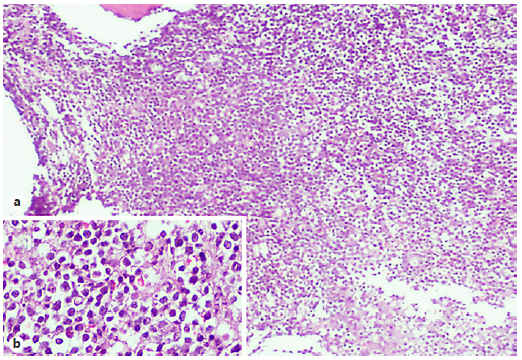

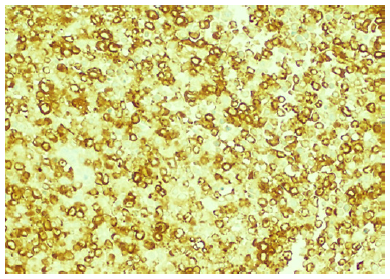

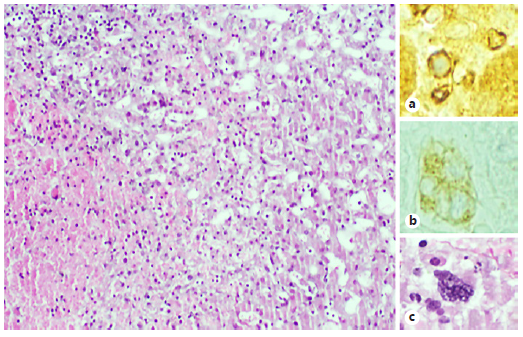

A 29-year-old previously healthy male presented to the emergency department with fatigue, jaundice, and epigastric and right upper quadrant abdominal pain with a 4-day duration. He denied nausea, vomiting, fever, malaise, anorexia, choluria, or acholia. The patient was haemodynamically stable, without fever. On physical examination, the patient was oriented, icteric, without flapping, with a distended and tender abdomen, with grade 2 ascites, and a palpable as well as painful liver. Complete blood count revealed anaemia (haemoglobin of 8.6 g/dL), with anisocytosis; leucocytosis (11,000 μL) with lymphocytosis (10,610 μL), and thrombocytopenia (< 10,000 μL). Marked elevations of liver enzymes [AST 118 times the upper limit of normal (ULN); ALT 172 times ULN], hyperbilirubinemia (2.8 g/dL), acute kidney injury (creatinine of 1.7 mg/dL), and lactacidaemia (8 mmol/L) as well as coagulopathy with an INR of 4.7 were noted. Severe acute liver injury was diagnosed based on the presence of coagulopathy in the absence of hepatic encephalopathy (HE). By then, the patient was admitted to the Intermediate Care Unit. The workup diagnosis excluded infection with acute hepatotropic viruses, autoimmune diseases, and Wilson disease. Abdominal Doppler ultrasound revealed hepatomegaly with a heterogeneous structure and low volume ascites as well as documented alterations in hepatic venous flow (no sure individualization of suprahepatic veins [SHVs]) with a filiform aspect of the inferior vena cava. Portal vein was patent with hepatofugal flow. The abdominal CT scan confirmed absence of flow at SHVs, and the diagnosis of BCS was established. Paracentesis revealed a serum/ascites albumin gradient (SAAG) > 1.1 g/ dL, and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis was ruled out. No anticoagulation treatment was immediately started due to severe thrombocytopenia and coagulation disorders. General supportive measures were initiated. The patient evolved with development of grade 2 West-Haven HE and severe coagulopathy (INR 4.76; FV 3.5%). By that time, and 4 days after initial hospital admission, the patient was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU), and listed for urgent LT. Repeated complete blood count revealed the presence of an increased number of myeloid blasts. A population of blast cells with abnormal immunophenotypic profile (CD33+ and myeloperoxidase, MPO+) was found in peripheral blood flow cytometry. Bone marrow biopsy was performed, and the morphological study revealed densely cellular medullary spaces, occupied by a population of medium-sized blast cells (Fig. 1). Immunohistochemical study demonstrated myeloid differentiation, with immunoreactivity to MPO (Fig. 2), CD68 (KP1 and PGM1 clones), CD15, and CD117. Therefore, the diagnosis of acute myeloid leukaemia FAB M1 was established. By this time, the patient was delisted due to the haematological malignancy and initiation of rescue chemotherapy was not possible due to liver failure. Symptomatic treatment was proposed. The patient died 48 h after admission in the ICU. The rapid progression to death is multifactorial in origin, due to multiorgan failure combined to palliative symptomatic treatment. Post-mortem liver biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of BCS, with concomitant extra-medullary haematopoiesis. No leukaemia cells were found in the liver biopsy (Fig. 3).

Fig. 1 Bone marrow biopsy showing (a) densely packed medullary spaces occupied by sheets of medium-sized blasts (H&E, 40×). The inset (b) illustrates this population in greater detail (H&E, 400×).

Fig. 2 The blast population shows frequent MPO expression, which demonstrates the myeloid differentiation (MPO, 200×).

Fig. 3 a The morphological study of the iver biopsy shows sinusoidal dilatation, atrophy of the trabecula, and areas of hepatocytes necrosis: these features are compatible with BCS (H&E, 100×). b Simultaneously, there is morphological evidence of extramedullary haematopoiesis, with easily identifiable megakaryocytes (H&E, 400×), and it was also demonstrated with immunohistochemical study to glycophorin that stains erythroid blasts (glycophorin, 400×) (c) and CD61 that stains megakaryocytes (CD61, 400×) (b).

Discussion

Patients with cancer have a derangement of the haemostatic system, increasing the risk of both haemorrhagic and thrombotic complications, particularly venous thromboembolism (VTE). This association is well described for solid tumours [12]. Although haemorrhagic complications were previously thought to be the most frequent complications of haematological malignancies, it is now known that these patients have a risk of VTE similar to the one described in patients with solid tumours, and in this particular population thrombotic events can be underestimated [12]. The episode of VTE can either precede the diagnosis or be the presenting event of the haematological malignancy [12].

Myeloproliferative disorders are the most frequent haematological neoplasms associated with BCS and are diagnosed in 30-50% of cases. Other haematological neoplasms are rarely associated to BCS [3, 6, 8], and, to our knowledge, there are only 3 reported cases with simultaneous hepatic vein thrombosis and AML as initial presentation [9-11]. All these cases are related to acute promyelocytic leukaemia, which is known to turn patients more susceptible to thrombosis besides bleeding disorders [13]. Our patient did not present with a M3, but rather M1 (acute myeloblastic leukaemia with minimal maturation) form of AML, which has never been associated to BCS before.

In the context of ALF, particularly if there is an indication for LT, an active search for malignant infiltration of the liver and active neoplasia is mandatory. This is of particular importance in the context of acute BCS, since malignancies, namely haematological, are frequently associated [2, 3, 6, 14]. In this particular case, the patient rapidly evolved from severe acute liver injury to ALF with the rapid onset of HE, motivating urgent LT referral. The active search for an aetiology justifying the aforementioned haematological abnormalities (severe thrombocytopenia and lymphocytosis) which could not be affiliated with the liver condition, led to prompt investigation of active neoplasia, which would contraindicate the LT.

With the present case, the authors wanted to underline: (i) the pro-thrombotic state associated with acute leukaemia, not usually associated; (ii) that severe thrombocytopenia did not protect from the thrombotic event; (iii) that acute thrombosis could, by means of platelet consumption, have some contribution to the severity of thrombocytopenia; and (iv) that a prompt search for active malignancy is mandatory in the context of ALF irrespectively of the aetiology, particularly when related to BCS. In this case, thrombosis of the SHVs was rather a consequence of a pro-thrombotic state in the context of acute leukaemia than the result of local factors associated with liver invasion by leukemic cells, as no infiltration was seen in the liver biopsy specimen. Yet, liver extramedullary haematopoiesis shall be considered as a local important factor in the genesis of a thrombotic event. This case clearly demonstrates the association of three rare entities: BCS, AML, and ALF altogether in which the treatment of one condition contraindicates the treatment of the other.