Introduction

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infects over 160 million people worldwide and is one of the main causes of chronic hepatitis and progressive liver damage, inflicting a higher risk for cirrhosis, end-stage liver disease (ESLD), hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), and death [1]. Haemophilia is a hereditary X-linked disorder caused by total or partial deficiency of coagulation factos VIII (haemophilia A) and IX (haemophilia B) [2,3]. They represent two of the most frequent hereditary bleeding disorders, with its prevalence estimated in 1-9/100,000 males [4]. The World Federation of Haemophilia 2017 report reveals that out of nearly 315,000 people with bleeding disorders, 196,700 are diagnosed with haemophilia, with Portugal contributing 705 cases (541 haemophilia A; 112 haemophilia B; 52 haemophilia type unknown) [5].

The advent of intravenous replacement of clotting factos radically improved the management of bleeding episodes, quality of life, and survival of these patients [6, 7]. Despite this improvement in care, the majority of severe patients treated with coagulation factors before the existence of viral inactivation procedures and the introduction of universal HCV screening in the 1990s were infected with HCV [8-14]. Progression to ESLD in persons with haemophilia (PWH) infected with HCV is believed to be similar to that seen in the general population [15].

The main goal of antiviral therapy in PWH is the same as for the general population, aiming to achieve sustained virologic response (SVR) and to prevent disease progression and liver-related complications [15]. Previous therapies based on interferon (IFN) had low efficacy, with SVR rates ranging from 50 to 60% [16], with major side effects and poor tolerability. Since 2014 several direct-acting antiviral (DAA) have been approved, leading to higher SVR rates of up to 100% with more favourable tolerability and safety profiles. Recommendations for antiviral treatment in PWH are the same as for non-haemophiliacs [15], despite limited clinical data regarding treatment outcomes on this subgroup of patients.

Our aim was to report the natural outcomes of HCVinfected PWH and the results of DAA therapy in a singlecentre cohort of patients with haemophilia.

Material and Methods

Patients and Data Collection

We performed a retrospective, single-centre study, including all PWH with positive HCV antibody, followed in our institution from January 1995 to December 2017. Data from medical records related to this period were retrieved. Patients were classified according to type and severity of haemophilia. First exposure to blood products was recorded and assumed as the probable date of infection. The severity of haemophilia was classified as mild (5-40% of normal factor level), moderate (1-5% of normal factor level), or severe (< 1% of normal factor level) [17]. Status regarding HBV and HIV infection were collected. HCV infection was characterized by HCV genotype, duration of infection (difference between probable date of infection and the end of treatment or follow-up), and type and duration of antiviral treatment used. Registered outcomes were rate of spontaneous clearance of HCV (anti-HCV positive with persistently negative viremia); clinical, analytical, and/or imagiological diagnosis of cirrhosis; SVR achievement; occurrence of HCC or variceal haemorrhage; allcause and liver-related mortality.

The study was approved by the local medical ethics committee.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the IBM Statistical Package for Social Sciences 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages, and continuous variables as means and standard deviation (SD) or medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) for variables with skewed distributions. Differences between groups were evaluated with Pearson χ2 test or Fischer’s exact test for categorical variables, as appropriate, and the Student t test for continuous variables. Variables with a significant p value in univariate analysis were included in the multivariable analysis (binary logistic regression). Statistical significance was set at p value < 0.05.

Results

Patient Population

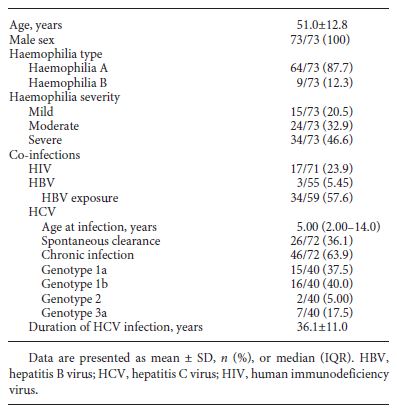

From 131 PWH, 73 (55.7%) had a positive hepatitis C antibody, all male gender and with a median age at the end of follow-up of 51 years (SD 12.8). From the 73 patients, one was lost to follow-up. The baseline characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1. The majority (87.6%) was diagnosed with haemophilia A, with 46.6% presenting a severe disease. The median age for first exposure to blood factors was 5 years (IQR 2.00-14.0), with 28.8% being exposed before the age of 2 years. Ergo, HCV duration of infection was assumed to be approximately 36.1 years (SD 11.0). Co-infection with HIV was present in 23.9% (n = 17), and 5.45% (n = 3) were HBsAg positive. Spontaneous clearance of HCV occurred in 36.1% (n = 26), with the remaining 63.9% (n = 46) developing chronic hepatitis C. Of these, HCV genotype 1 was the most common (n = 31, 77.5%).

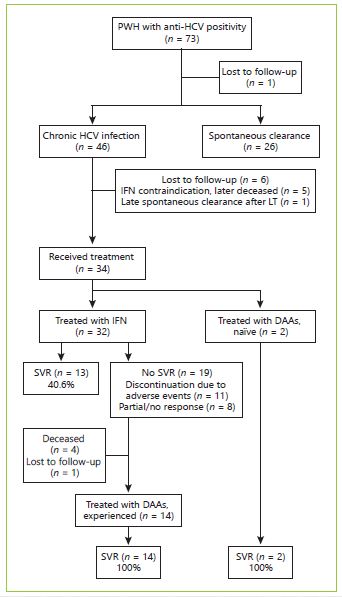

Treatment

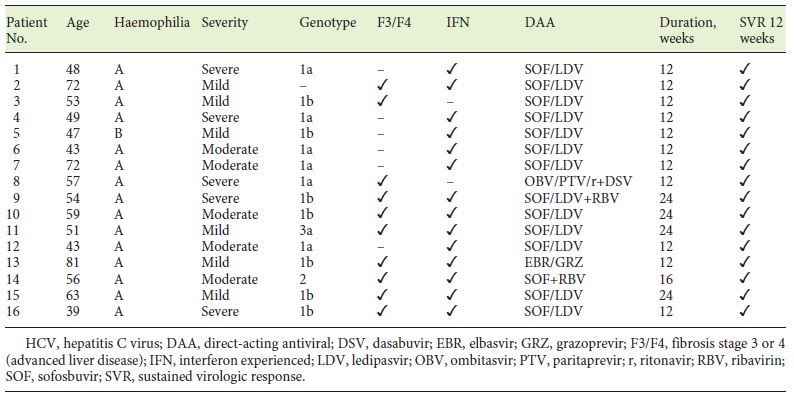

In our cohort, 34 (out of 46) patients with chronic hepatitis C were treated as shown in Figure 1. Most patients were firstly treated with IFN-based regimens (n = 32) with SVR rates of 40.6%. Eleven patients discontinued the treatment due to adverse events and 8 due to partial or no response. Treatment with DAA was pursued in 14 IFN experienced and 2 naïve patients. The most common DAA-treatment regimen was the combination of sofosbuvir and ledipasvir for 12 to 24 weeks. The overall SVR rates were 100% (Table 2).

Table 2. Summary of patient characteristics and treatment outcomes in haemophilic patients with chronic HCV infection treated with DAAs

Clinical Outcomes

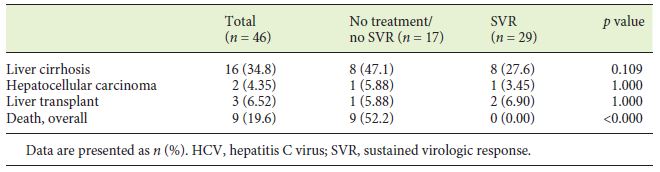

Cirrhosis and ESLD

From first blood products exposure, a median follow up time of 40 years (IQR 34.5-45) was observed. During this period, cirrhosis developed in 16 patients, corresponding to 34.8% and an incidence rate of 0.9 per 100 patient-years. The association of chronic HCV infection with the development of cirrhosis was statistically significant (p = 0.003) (Table 3). HBV exposure (anti-HBc+) and HBV (AgHBs+) and HIV infection were all associated with cirrhosis development, although without statistical significance (p = 0.059, p = 0.053, p = 0.056, respectively). From the 16 cirrhotic patients, 2 complicated with HCC and 3 were transplanted successfully due to hepatic decompensation (Table 3).

Mortality

Overall, 17 patients died during the follow-up period (23.3%) with an annual mortality rate of 0.68% per year. The mean age at the time of death was 48.4 years (SD 15.4 years). The cause of death was attributable to liver disease in 4 patients (variceal bleeding n = 2; HCC n = 1; sepsis n = 1), representing 23.5% of all deaths. All haemophiliarelated deaths (n = 7, 41.2%) were the consequence of intracranial haemorrhage. HIV evolution to acquired immunodeficiency syndrome was responsible for 2 deaths (11.8%). Overall, higher mortality rates were observed in severe haemophilia (39.4 vs. 10.3%, p = 0.004), in chronic HBV-infected patients (AgHBs+) (66.7 vs. 5.8%, p = 0.019), and in HIV-positive patients (64.7 vs. 11.3%, p < 0.001), as well as in cirrhotic patients (43.8 vs. 17.9%, p = 0.046), more evident for those with portal hypertension (50.0 vs. 12.5%, p = 0.015) and patients who had not achieved SVR (100 vs. 0%, p < 0.001). However, none of these variables was found significant on multivariate analysis.

The number and the mean age at the time of death were not significantly different between the spontaneous clearance and chronic HCV groups (Table 3). In the chronic HCV group, all deaths (n = 9) occurred in patients who had not achieved SVR (p < 0.001) (Table 4). Only 1 death occurred in 2017, with all the others occurring before 2010 and DAA introduction.

Discussion

The availability of clotting factors for PWH significantly enhanced the management of bleeding episodes, the safety of invasive procedures, their quality of life, and overall survival [6, 7, 18, 19]. Before the 1990s, such factors did not undergo viral inactivation procedures, which led to HCV transmission to haemophiliac patients [20, 21]. Besides the inexistence of viral inactivation mechanisms, the concentrates were prepared from large pools of plasma, and so it is agreed that virtually all patients treated with these products were infected with HCV at the time of the first infusion [8, 22]. The haemophiliac population represents the possibility of getting as close as possible to the natural history of HCV infection. In fact, this natural history is intricate to study because of the dissimilar way of contracting the disease in different patients, the difficulty in determining the moment of infection, the general lack of compliance during follow-up, and the necessity of a long period of time to assess a disease with such a slow progression. Our patients represent an exceptional model to study the natural course of this infection. They are a homogeneous group of people, with the same gender, with the same route of infection acquisition, and in whom we can reliably define the date of infection. They also have a long duration of infection, allowing us to get access to the true natural history of this disease.

Seroprevalence of anti-HCV in the Portuguese haemophiliac population is largely unknow. Data from our centre reveals a decreasing seroprevalence over time, with 62% of PWH being seropositive in 1990, 51.1% in 2000 [23], and 32,3% currently (unpublished data). Rocha et al. [24] reported positivity for anti-HCV in 21.4% of the patients treated for haemophilia at another tertiary centre between 2011 and 2013. Before HCV direct screening measures were established, 80% of PWH experienced chronic hepatitis C and about 20% progressed to liver cirrhosis within 30 years [25]. In our cohort, spontaneous clearance of HCV occurred in 35% of the patients, which stands between values of 20-40% reported in some studies [26, 27]. Also, approximately 30% of patients evolved to cirrhosis [28]. This slightly different value can be explained by the longer follow-up of our study as well by the drop-out rate in which we could have lost some patients that would not progress to cirrhosis. As a fact, our lost-to-follow-up population (n = 8) consisted of a PWH/HCV+ with no other information regarding evolution of HCV infection, patients who were not proposed for IFN therapy (n = 6), and a PWH treated with IFN and lost to follow-up without any subsequent information. Our data is also compatible with that of other cohorts [29], showing a lower mean age of infection than that of the general population at risk for HCV due to haemophilia treatment with inactivated plasma products from childhood.

Patients with spontaneous clearance of the virus were also included, eliminating selection bias that may occur when the exclusion of such patients conducts to worse prognosis and outcome of the disease.

Treatment provides the best weapon to change the natural history of HCV infection. The effectiveness of IFN regimens appears to be similar to the general population, with overall SVR rates reaching 60% [16]. Higher rates of SVR are observed in HIV-negative and in the treatment of naïve haemophiliac patients, ranging from 45% for genotype 1 to 79% for non-1 genotype [30]. The SVR rate of 41% observed in our cohort is in accordance with these data. The slightly lower value could be explained by treatment discontinuation secondary to side effects and a predominance of poor prognostic factors of our patients such as male gender, genotype 1, and long duration of infection.

With the development and approval of DAA drugs, the treatment of HCV has witnessed a true revolution, with patients achieving higher rates of cure with significant less adverse events and shorter time regimens [29]. Initial studies on DAAs did not include patients with special comorbidities, as real-life studies lacked significant data for patients with inherited haemorrhagic disorders [31]. IFN- and RBV-free regimens with LDV/SOF resulted in early HCV suppression that continued throughout the duration of treatment and post-treatment [32]. Our cohort of patients treated with DAA was composed of IFN-experienced patients in 87.5%, and 62.5% had signs of advanced liver disease. Our SVR rates results were excellent (100%) and comparable to other cohorts results [29, 33]. Stedman et al. [33] studied the effect of SOF/LDV+RBV on 14 haemophiliacs, 2 von Willebrand and 1 patient with factor XIII deficiency. All patients achieved SVR12 with no safety concerns associated with the patients’ underlying bleeding disorders [33]. Walsh et al. [34] also concluded that SOF/LDV for patients with HCV genotype 1 or 4 infection or SOF+RBV for patients with genotype 2 or 3 infection was highly effective and well tolerated among those with inherited bleeding disorders. Nagao and Hanabusa [35] studied 43 patients with haemophilia with genotype 1 or 4 HCV treated with SOF/ LDV and showed effectiveness and safeness, but with SVR in patients with cirrhosis being lower than that in the non-cirrhotic group, stressing the need for treatment as early as possible, ideally before the onset of cirrhosis. Papadopoulos et al. [31] summarized all available DAA studies in inherited bleeding disorders, showing an overall SVR > 95% with SOF/LDV regimens.

Despite these encouraging results with DAAs, in our cohort, only 34 out of 46 patients with chronic HCV (73.9%) received treatment and only 29 of these patients achieved SVR (85.3%) overall. This was mainly a result of patients lost to follow-up (n = 8) or IFN contraindication (n = 5) and adverse events/no response (n = 4) in patients who did not survive to meet the DAA era.

Mortality of PWH is known to be 2-5 times higher than that of the general population [36], which can reach 16 times higher in the setting of cirrhosis and HCC [10]. Some studies also showed a significant proportion of ESLD in a cohort of 863 HCV-infected patients with inherited bleeding disorders, stressing out HCC as an increasing problem [37, 38]. In our cohort, we only found differences in mortality between the chronically infected patients with or without SVR. This probably reflects the avoidance of progression to ESLD. The mortality rate in our cohort was 23.3%, with its main cause related to bleeding events, which could be explained by the relatively young age at the time of death and higher proportion of patients with severe haemophilia. Besides haemophilia severity, we also observed a higher mortality rate in HBV/HIV co-infection and in cirrhotic patients. Our global mortality rate is in line with a 10-year survival pointed out between 82.1-95.3% for PWH mono- or coinfected with HIV [39]. Of note, only 1 death occurred after DAA introduction, for which no conclusions can be drawn on the effect of DAA treatment on PWH survival, although a reduced mortality in this population with SVR would be expected as compared to other populations (including those with cirrhosis) who attained SVR.

Our study has some limitations. Firstly, it was performed in a single tertiary centre and a small patient population was included. Secondly, it was retrospective in nature and a significant number of patients were lost to follow-up, meaning there are some missing data and the quality of data may be suboptimal. Also, information about alcohol consumption was not available.

However, our study has also a few strengths. Considering the rarity of haemophilia in the general population, we have included a representative sample of Portuguese PWH, with a notable follow-up of 22 years and an approximate 36 years of HCV infection evolution, necessary to study the occurrence of some of our outcomes. Also, this is the first study evaluating the efficacy of hepatitis C treatment and clinical outcomes in haemophiliac patients of the Portuguese population.

In conclusion, this study describes (1) the natural history of a cohort of 73 Portuguese PWH with hepatitis C exposure after two decades of follow-up, (2) hepatitis C treatment results with a special focus on direct antiviral agents, and (3) clinical outcomes of these patients. It corroborates evolution to chronic hepatitis C infection in 63.9% of the patients and progression to liver cirrhosis in 34.8% of them. IFN-based regimens achieved SVR rates of 40.6%, probably conditioned by poor prognostic factors of our patients such as male gender, genotype 1 predominance, and long duration of infection, while DAAs achieved an outstanding 100% SVR rate despite most of the patients being IFN-experienced and having advanced liver disease. We reported an overall mortality rate of 23.3%, lower than previously described. Of these, only 23.5% were related to liver disease and all of them occurred in chronic hepatitis C patients who had not achieved SVR. Our results demonstrate response rates to HCV treatment in haemophilia patients comparable to those in the general population and stress the importance of early treatment to avoid chronic liver disease progression as well as related morbidity and mortality. DAAs might represent one of the long-awaited shifts in the care of PWH.