Introduction

Liver involvement is frequent in advanced systemic hematologic disease [1-3] (10% of non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas) [4], but primary liver lymphomas (PLLs) are rare [5]. The diagnosis is usually late, and prognosis is poor [5]. Earlier diagnosis is associated with better survival [6], and therefore this condition should be considered in the approach of a patient with liver disease. We present a case of a patient with PLL with multiple nodular lesions.

Case Report

We present the case of a 59-year-old female evaluated for abdominal pain in the right hypochondrium, persistent for 1 month and a half. The pain had a sudden onset and was progressively worsening, and aggravated with deep inspiration. The patient also referred progressive tiredness, weight loss (not quantified) and night sweats, without fever. Personal history included asthma and seafood atopy. A family history of gynecologic (breast and uterus) and gastrointestinal (stomach, intestine, hepatocellular carcinoma) neoplasms was also recorded. The patient denied exposure to ionizing radiation or chemicals, recent travelling prior to the onset of symptoms, drinking unsafe water, or ingesting untreated dairy products. One year before, she underwent upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and abdominal ultrasound for dyspepsia, as well as total colonoscopy for colorectal cancer screening, both exams were normal. Blood analysis performed at that time showed no alteration. She was initially medicated with analgesics with incomplete symptomatic relief.

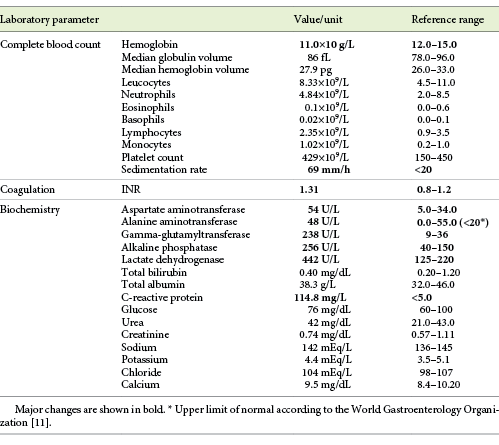

The blood analysis revealed normocytic anemia without other changes in blood count, and cytocholestasis without hyperbilirubinemia (Table 1). Tumor markers (alpha-fetoprotein, CEA, CA19.9), hepatotropic virus serology (HBV, HCV, HIV, EBV), and the liver autoimmunity study were all negative.

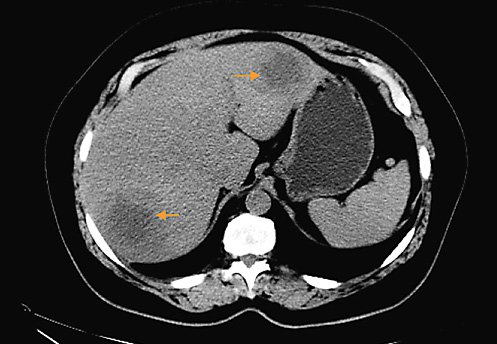

An abdominal and pelvic ultrasound was performed, which revealed three solid nodules in the liver. These were first characterized by computed tomography (CT) scan and then by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): two in the right lobe (segment VII and V), both with about 6 cm, and one in the left lobe, with about 4.5 cm, all of them with restricted diffusion and central necrosis suggestive of secondary deposits, in a liver without stigmas of chronic liver disease. Adenomegalies and splenomegaly were excluded.

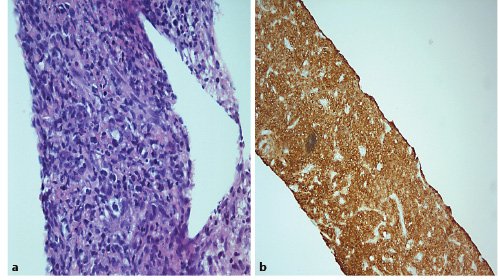

Subsequent thoracic, abdominal, and pelvic CT scan (Fig. 1) excluded other lesions, including primary lesions suggestive of neoplastic disease. A positron emission tomography scan (PET scan) was not performed. A CT-guided biopsy of the liver lesions was made, revealing a diffuse large germinal center B-cell-like lymphoma expressing CD10+, blc-6, and MUM1, without rearrangement of the MYC and BCL2 genes (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. a Large and blue cell hepatic infiltration whose immunohistochemical profile is: CD20(+), CD3(-), CD5(-), CD10(+), BCL2(+) heterogeneous labelling, BCL6(+), MUM1(-), Cyclin D1(-), MYC(+). The Ki67 expression is 70%. HE 400×.bImmunohistochemical stain CD20(+) in tumoral liver specimen. HE 200×.

Medullary involvement was excluded with bone biopsy, and therefore the diagnosis of primary hepatic lymphoma was assumed. At the time, the patient was slightly symptomatic, but still capable of performing daily activities without help (ECOG Performance Status 1).

The patient is undergoing chemotherapy with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisolone (R-CHOP), and has already received 4 cycles, with good tolerance.

Discussion/Conclusion

PLL is a rare entity due to the lack of abundant lymphoid tissue in the normal liver [7]. It corresponds to 0.4% of extranodal lymphomas and 0.016% of non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas [5,8]. It most commonly affects male patients (2:1) aged between 50 and 62 years [2,8,9]. Usually, primary lymphomas develop in patients with previous liver disease: association with viral infection (HCV, HBV, EBV, HIV), autoimmune diseases, immunosuppression [2,10], liver cirrhosis [7,9], and exposure to chemicals [8] were described.

Clinical manifestations of PLL are nonspecific. In most cases, the main complaint is abdominal discomfort due to liver distension [11]. Classical B symptoms (fever, weight loss, night sweats) are usually present (up to 85%), but may be absent [7].

The blood analysis commonly reveals altered liver biochemistry, particularly cholestasis due to the hepatic infiltration (present in up to 70% of cases) [6]. Alpha-fetoprotein and CEA values are normal in most cases and may help in the differential diagnosis [4,9].

Most cases of PLL present with nodular solid lesions, either single (33-60%) or multiple (33-50%) [4,12-14]. These present an expansive and destructive pattern in CT and MRI. Therefore, they are often confused with metastatic lesions [2,6,13,15]. Diffuse infiltrative lesions are rare [1,6] and, when present, usually invade portal tracts and sinusoids [6]. This pattern is rare in Caucasians [4] and more common in Chinese patients [4,16].

Histologic diagnosis is done by biopsy of the lesion, which shows lymphoma infiltration. Non-Hodgkin B-cell lymphoma is the most frequent, followed by T-cell lymphomas. Overall, the most common histologic result is diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), a subtype of non-Hodgkin B-cell lymphoma [2,4,7,8,10]. This is an aggressive lymphoma, associated with rapid growth. DLBCL may be classified according to Hans et al. [17] by immunohistochemical stain expression as germinal center B-cell-like and non-germinal center B-cell-like. The germinal center B-cell-like profile (CD10+, blc-6, and MUM1), as in this case, yields a better prognosis [17]. The absence of documented MYC and BCL2 mutations allowed the classification of the lymphoma as a double-expressor.

There are some PLL reported in the literature, generally diagnosed on the basis of nonuniform criteria, as there are no consensually accepted diagnostic criteria.

Caccamo et al. [18] considers PLL a lymphoma limited to the liver, whose symptoms should be explainable exclusively by liver involvement, without evidence of extrahepatic localization (superficial lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, abnormal hematological parameters, spleen, or bone marrow) over a period of at least 6 months after appearance of the hepatic lesions. These criteria were proposed in 1986 based on a patient with Kaposi sarcoma and with gastric mucosa and abdominal lymph node affection [19].

In 1995, Lei et al. [11] proposed that the diagnosis of PLL should be made by the cumulative presence of symptoms caused mainly by liver involvement at the time of presentation, absence of distant lymphadenopathy (palpable clinically at presentation or detected during staging radiologic studies), and the absence of a leukemic blood picture in the peripheral blood film. More recently, in 2001, Emile et al. [3] adopted the criteria Lei et al. [11], but added that presence of lymphomatous infiltration of the hepatic hilum, spleen, or bone marrow at the time of diagnosis should not exclude the diagnosis of PLL.

Due to the lack of uniform diagnosis criteria, some published case reports might correspond to metastatic hepatic lymphoma instead of real primary lymphoma. Also, the criteria proposed by Caccamo et al. [18]might lead to a delay of 6 months to establish the diagnosis, with prognostic implications.

In this case report, the diagnosis of PLL was based on the exclusive liver involvement with documented absence of extrahepatic involvement (lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, and secondary lesions) [1,11].

Some authors excluded the presence of extrahepatic disease by CT scan [4,9], whereas others used FDG-PET [10], since it has a higher sensitivity for the diagnosis of extrahepatic lesions [19]. Ugurluer et al. [8], in a series of 41 patients diagnosed with primary liver disease between 1977 and 2014, showed that 63.4% underwent CT scan and 56.1% ultrasound, whereas a PET scan was performed in only 14.6% of the patients. Although we agree that FDG-PET scan would have been the best exam for diagnosis and staging, it was not readily available and therefore was not performed, as postponing the initiation of chemotherapy would have prognostic consequences.

Evidence on the optimal therapy for PLL is very scarce [8]. The most commonly used regimens involve R-CHOP [7] which is the first-line chemotherapy for germinal center type non double-hit DLBCL in advanced Ann Arbor stage (III-IV).

Survival may exceed 13 years, with average disease-free survivals of 69% at 5 years and 56% at 10 years [8], but varies greatly according to the stage of disease at diagnosis (early diagnoses are associated with better prognosis) [6].

Central nervous system (CNS) affection in DLBCL is rare, and the decision for prophylactic chemotherapy should be individualized [20]. In this case, according to the Central Nervous System-International Prognostic Index (CNS-IPI) score, the patient had an intermediate risk (3.4%) of recurring in the CNS [21], and therefore no prophylactic CNS chemotherapy was performed.

In conclusion, the diagnosis of PLL should be considered in the differential diagnosis of hepatic nodular lesions, even in patients without identified predisposing conditions. Its diagnosis requires high clinical suspicion and is established histologically. Given the rarity of the disease, it is important to define universal, consensual diagnostic criteria, which would allow diagnostic standardization and thus a better clinical knowledge of the entity and its response to different possible therapeutic regimens.