Introduction

Fat tissue, being metabolically active, can undergo ischemic transformation, sometimes resulting in a mass-like encapsulated fat necrosis (EFN). EFN was first described in the breast, but it can occur anywhere, including in the intraperitoneal space. The pathophysiology behind this entity is not well understood, but trauma and ischemia are the most accepted causes leading to adipose tissue lobule infarction. [1,2] Greater omentum or epiploic appendage torsion and infarction are the most common types of EFN [3].

Antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) is characterized by a combination of anti-phospholipid antibodies and recurrent vascular thrombosis [4,5]. Vascular thrombotic events include thrombotic microangiopathy and may compromise capillaries, arterioles, or venules of different organs and tissues, eventually leading to ischemia and organ failure [2].

Case Report and Case Presentation

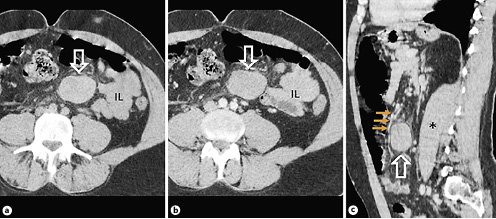

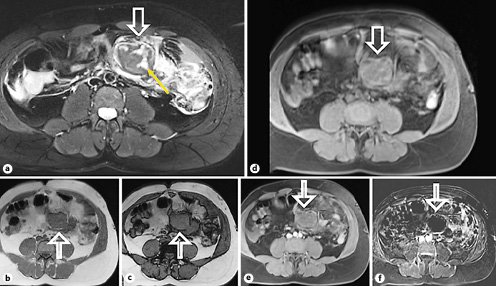

A 42-year-old male patient was admitted to the emergency department with abdominal pain for the past month. Other symptoms included fever and weight loss, and changes in bowel habits were denied. There was no past history of trauma or intra-abdominal inflammatory disease such as pancreatitis. The patient had APS with multiple venous thromboembolic events. This included episodes of deep vein thrombosis at 16 and 18 years of age, pulmonary embolisms at 23 and 41 years, and an ischemic stroke at 38 years affecting the left vertebral artery. There was also an episode of APS-associated lower limb vasculitis, currently resolved. He was treated with warfarin, with regular monitoring of his international normalized ratio, with a target between 3 and 4. Physical examination revealed diffuse abdominal tenderness, slightly more pronounced on the left upper and lower quadrants, without peritonism and palpable masses. Blood results were unremarkable. The patient underwent a contrast-enhanced abdomen and pelvis computed tomography (CT) scan at another institution a few days prior to this presentation (Fig. 1). The scan revealed a left-sided mass adjacent to the ileal bowel loops, displacing the mesenteric vessels and measuring 5 × 3.7 cm (axial plane). The ileal bowel loops were displaced; however, no bowel obstruction was reported. The mass was heterogeneous, non-calcified, with lobulated margins, mostly isodense compared to muscle tissue on unenhanced images, without manifest enhancement on post-contrast acquisitions (arterial and portal-venous phases). Small regional lymph nodes and a moderate amount of peritoneal free fluid were also recognized. A gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance (MR) of the abdomen and pelvis was performed at our institution (Fig. 2) for a more accurate characterization. It confirmed the presence of an encapsulated mesenteric mass, slightly greater in size compared to the previous CT, with 5 × 4 cm (axial plane). It was isointense compared to the muscle tissue on T1-weighted images and mostly hypointense on T2-weighted images, with small hyperintense internal areas. The mass had no signs of intra- or extracellular fat components, and no restricted diffusion was noticed. Intravenous administration of gadolinium showed no significant contrast uptake. Reactive findings with progressive contrast enhancement of the adjacent fat tissue and peritoneal layers were seen.

Fig. 1. Non-enhanced (a) and post-contrast abdominal CT scans (b) showing a well-defined, non-calcified mesenteric mass (arrows), with approximately 50 Hounsfield units, with adjacent fat stranding. No significant contrast uptake and no bowel obstruction are noticed. On the sagittal post-contrast CT scan (c) the mesenteric mass (arrow) is between and displacing mesenteric vessels (small arrows). IL, ileum bowel loops; asterisk, left psoas muscle.

Fig. 2. MR scans (a-f) showing the mesenteric mass (arrows), with internal areas of edema on a T2-weighted image (yellow arrow ina). The mass shows no signs of intracellular fat content on the in-phase (b) and out-of-phase (c) T1-weighted images. No extracellular fat is seen on the fat-suppressed T1-weighted image (d). Fat-suppressed T1-weighted after gadolinium administration (e) and its respective subtraction sequence (f) show no contrast uptake.

Taking into account these clinical and radiological findings, the described mesenteric mass could represent a desmoid tumor, mainly due to the fact that it did not demonstrate significant enhancement after intravenous contrast administration. A mass-like encapsulated steatonecrosis was also suspected, considering the absence of post-contrast enhancement and the patient’s medical history of APS with multiple venous thromboembolic events. However, fat imaging signs were absent, both on CT and MR, and the mesenteric root is an uncommon lo cation for steatonecrosis. Surgical excision of the mesenteric mass together with two adherent distal ileum segments was performed.

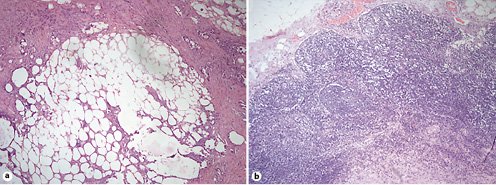

Macroscopically, the mass was encapsulated, with a smooth outline and elastic shape, in the subserosa of the ileum. Microscopic histological analysis (Fig. 3) showed the mesentery with areas of organizing panniculitis, steatonecrosis, and hemorrhage, surrounded by an inflammatory infiltrate with abundant lymphocytes and histiocytes.

Discussion and Conclusion

Intraperitoneal focal fat infarction includes acute abdominal clinical conditions in which focal fatty tissue necrosis represents the common pathological factor. In clinical practice, most cases of intraperitoneal focal fat infarction concern torsion and/or infarction of the greater omentum or epiploic appendages. To our knowledge there are very few cases of mesenteric EFN described in literature [3].

Despite the location, the most common imaging feature of EFN on CT and MR scans relates to its fat content: CT scan shows low-density internal areas, and MR usually shows signs of intra- and/or extracellular internal fat content (signal drop on fat-suppressed T1- or T2-weighted images and also on the out-of-phase T1-weighted images). EFN may display a surrounding capsule, which can enhance after intravenous contrast administration. The infarction’s microscopic appearance changes over time: firstly, hemorrhagic infarction with fat necrosis is appreciated, followed by infiltration by lymphocytes, histiocytes and fibroblasts, the latter leading to fibrosis and scar tissue formation [2,3,5].

This case report describes a mesenteric mass-like fat necrosis in a patient with APS, without fat content imaging signs, which were probably obscured by the presence of extensive panniculitis and inflammatory cells, as demonstrated above in the microscopic analysis. Patients with APS have a higher incidence of vascular and microangiopathic thrombosis, which we considered to be the main cause for EFN formation described in this case report. Moreover, some authors state a possible association, though rare, between APS and vascular inflammation [6,7]. Since the patient had a previous lower limb vasculitis episode, we think that reactive inflammatory vasculitis could be an additional cause for the pathophysiology of fat necrosis.

Fat necrosis can cause abdominal pain, which can clinically mimic an acute abdomen. From a radiological point of view, if fat content was evident, liposarcoma would be the most important differential diagnosis. In our case, desmoid tumor was also considered, although lower to intermediate signal intensity would be expected on T1-weighted images. Desmoid tumor’s signal intensity is variable on both T2-weighted and after gadolinium administration images, depending on the histological component. The ENF natural temporal evolution is size reduction [2,3,8].

In conclusion, the purpose of this article is to describe a rare case of mesenteric mass-like EFN, with an uncommon association with APS and with an atypical imaging presentation due to the absence of fat content features.