Introduction

Dieulafoy’s lesions (DL) are relatively rare, being responsible for approximately 1.5% of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) and for nearly 3.5% of jejunoileal bleeding [1-3]. These lesions are responsible for severe acute UGIB episodes, which are usually life-threatening, recurrent, and very often present a major diagnostic challenge [4].

Upper GI endoscopy (UGIE) is the usual tool for gastric DL diagnosis, although it can fail in up to 30% of cases [5], especially in the absence of active bleeding. In these cases, endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) can be useful to confirm the diagnosis [6, 7]. The therapeutic role of EUS in managing GI bleeding when conventional endoscopic therapies fail has rapidly evolved [8]. EUS-guided therapies include injection of vasoconstrictor or sclerosing drugs, coil embolization, and subepithelial tattoo for posterior endoscopic band ligation [9]. Furthermore, EUS can be used to guide alternative endoscopic or radiologic procedures [9] and to confirm therapeutic success by demonstrating absent blood flow after therapy [6].

The authors report a unique case of recurrent UGIB due to two metachronous gastric DL in the same patient and emphasize the important role of EUS in the diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of these lesions, as well as its usefulness when associated with other techniques.

Case Presentation

A 28-year-old male was admitted in the emergency room with acute UGIB presenting with hematemesis and syncope. There was no remarkable past medical history and no features of chronic liver disease on physical examination. The patient denied alcohol abuse, smoking habits, and chronic or recent medication intake, namely nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. At admission, he was hypotensive and presented blood in the nasogastric tube, requiring transient vasopressor support, and was admitted in the Intensive Care Unit. The UGIE revealed fresh blood and a giant clot in the stomach covering the gastric body and fundus, as well as blood clots in the duodenum. A few hours later, the patient underwent a second-look UGIE that showed no mucosal defect. A DL was suspected and the patient underwent EUS, which was performed using a systematic gastric wall evaluation, showing an abnormal submucosal vessel on the posterior wall of the gastric body, close to the splenic hilum. EUS-guided sclerotherapy with 6 mL of polidocanol 2% was performed. The patient was discharged after 5 days, when hemodynamic, clinical, and laboratory stabilization was achieved. Twenty-four hours after hospital discharge, he was re-admitted with UGIB and, once again, the UGIE presented digested blood and clots but could not identify the bleeding source. A new EUS was performed, identifying a clot on the greater gastric curvature, in the same location as the previously treated DL. An attempt of EUS-guided hemostasis with through-the-scope clip triggered oozing bleeding, further controlled with endoscopic 15 mL of adrenalin and 14 mL of polidocanol injection and additional through-the-scope clips. After stabilization, the patient was discharged with an outpatient EUS appointment within 2 weeks to confirm vessel obliteration. However, 10 days after hospital discharge, the bleeding recurred with associated hemodynamic instability. UGIE displayed a visible vessel, without any of the previously placed clips in situ. Endoscopic hemostasis was achieved with 13 mL of adrenalin and 3 mL of polidocanol injection plus clips. The follow-up EUS still identified a feeding vessel arising from the splenic artery and penetrating the gastric muscularis propria (Fig. 1), not successfully obliterated with previous endoscopic therapy. The patient was referred to interventional radiology for embolization. Selective splenic artery angiogram identified a short gastric artery ectasia and hypervascularization (Fig. 2, large arrow) as well as the previously endoscopically placed hemoclips (Fig. 2, small arrow), which allowed transcatheter arterial embolization (TAE) with micro-coils. The patient underwent EUS evaluation 1 month after TAE that documented successful vessel obliteration.

Fig. 1 Endoscopic ultrasonography showing feeding vessel arising from the splenic artery, penetrating the gastric muscularis propria (Dieulafoy’s lesion).

Fig. 2 Selective splenic artery angiogram showing a short gastric ectasia and hypervascularization (large arrow) as well as hemoclips (small arrow).

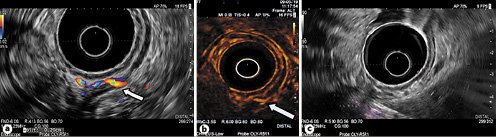

After 3 years free of bleeding manifestations, the patient presented with another episode of UGIB with hemodynamic instability. UGIE identified a small depressed area with a pulsatile, nonactively bleeding vessel, in the medial part of the gastric body anterior wall - a new DL location. Since the patient was hemodynamically unstable, this area was marked with a hemoclip, and CT angiography was performed in attempt to locate and possibly treat the source of bleeding. However, this method showed no active bleeding source. EUS revealed a feeding vessel, corresponding to a second DL, arising from the left gastric artery (Fig. 3a, b) while confirming obliteration of the previously treated lesion (Fig. 3c). The patient underwent selective left gastric artery angiogram, with identification of an abnormal vessel adjacent to the clip, and TAE could be performed (Fig. 4). The patient has evolved favorably with no further episodes of GI bleeding.

Fig. 3 a Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) revealing a feeding vessel (second Dieulafoy’s lesion) arising from the left gastric artery. b Feeding vessel visible with SonoVue. c EUS confirming obliteration of the previously treated Dieulafoy’s lesion.

Discussion/Conclusion

DL is a dilated aberrant submucosal vessel that does not undergo normal branching, unlike normal vessels which become progressively smaller when penetrating the GI wall. This results in a submucosal vessel with a large caliber (about 10 times the normal caliber of mucosal capillaries), despite its superficial location in the GI wall [10]. When this vessel erodes the overlying epithelium, in the absence of a primary ulcer, it typically produces severe acute onset bleeding without prior symptoms and often causes hemodynamic instability and requires several blood transfusions.

DL is a rare cause of GI bleeding. There are only 2 reported cases in the literature of life-threatening UGIB caused by two synchronous DL, one case with DL in the stomach and jejunum [11] and another with two gastric DL [12]. To the best of our knowledge, there are no reported cases of two metachronous DL.

UGIE is the first diagnostic approach recommended for detecting DL, and it is particularly helpful during active bleeding [7, 13]. In this scenario, arterial pumping may be visualized in an area without a clear visible ulcer. In the absence of active bleeding, a DL may appear as a raised nipple or visible vessel. Nevertheless, UGIE is only diagnostic in 70% of the patients. In up to 30%, these lesions may be missed due to small size, intermittent bleeding, location between gastric folds or under gastric contents, or adherent clot [5].

EUS is a technique that has proven to be useful to confirm the diagnosis in patients with suspected UGIB caused by DL [6, 7]. Typical EUS features include an abnormally large, 2- to 3-mm caliber, pulsatile, high-flow submucosal artery, usually located along the lesser gastric curvature near the gastroesophageal junction. In the present case, EUS was extremely important for diagnosing the UGIB etiology. In our hospital, it is common practice to perform EUS in cases of severe UGIB, clinically suggestive of a possible DL, after an inconclusive UGIE manifested as hematemesis. A systematic and thorough gastric evaluation performed by an experienced EUS operator is mandatory for optimizing detection of a possible DL. In this patient, the systematic assessment of the gastric vasculature by EUS allowed the diagnosis of DL after a single UGIB episode.

Several approaches for endoscopic hemostasis have been shown to be effective for DL, including a combination of epinephrine injection followed by bipolar probe coagulation, heater probe thermal coagulation, argon plasma coagulation, through-the-scope or over-the-scope clip placement, band ligation, and cyanoacrylate injection [3, 14-17]. EUS has also evolved to guide treatment of GI bleeding caused by DL, mainly in a nonactive bleeding setting. It may also be used to guide other nonendoscopic techniques, such as interventional radiologic therapy [9], through marking the blood vessel location. There are several EUS-guided procedures that can be used to treat DL, including adrenalin, polidocanol, or cyanoacrylate injection. EUS also allows lesion marking with a subepithelial tattoo or clip to direct further endoscopic hemostasis in cases of rebleeding [9]. After a first endoscopic treatment session, additional options include repeating endoscopic hemostasis, attempting EUS-guided therapy, angiographic embolization, or surgical wedge resection of the lesion. This patient presented recurrent episodes of UGIB despite multiple endoscopic and EUS-guided hemostasis, ultimately requiring radiologic intervention. The metallic clips used to mark the lesion site and placed with EUS guidance helped in directing endovascular intervention, emphasizing the important role of EUS in the management of DL.

Finally, additional benefits of EUS include the ability to confirm the efficacy of endoscopic hemostasis of a bleeding DL by demonstrating absent Doppler flow after therapy [6]. In our institution, we also routinely perform EUS after endoscopic hemostasis to confirm vessel obliteration [18]. This patient underwent several EUS in the follow-up, which documented successful obliteration of the first treated DL.

In conclusion, the authors report a unique case of severe, recurrent UGIB caused by two metachronous gastric DL in the same, otherwise healthy, young patient. This case report emphasizes the value of a systematic EUS evaluation of the GI wall if a DL is suspected. In addition, we acknowledge the outstanding role of EUS in the treatment and follow-up of these lesions, as well as in association with other techniques, such as TAE.