Introduction

Pediatric lower gastrointestinal bleeding (LGIB) in the emergency setting is rare, being observed in <1% of children attending the emergency department [1]. When the source of the hemorrhage is beyond the ligament of Treitz, the typical presentation is bleeding per rectum. The blood passed out is bright red when the transit time is <14 h, beyond which breakdown of hemoglobin leads to melena [2].

The presentation of bouts of bright red rectal bleeding with accompanying anemia in a child can be an alarming symptom to the parents. The paper discusses the presentation and management of an interesting case of bowel arteriovenous malformation (AVM).

Case

A 12-year-old girl presented with malaise and passage of frank blood in stools for a week. Her mother denied a history of fever, vomiting, and abdominal pain. Episodes of painless bright red blood per rectum were reported. On examination, she was alert, active but sick looking, and markedly pale. Abdomen examination was unremarkable, including inspection of the anus and rectal examination for fissures, polyps, and prolapse. Investigations revealed a hemoglobin level of 6 g/dL; other baseline tests were within normal limits. Stool culture was negative for pathogens such as enteropathogenic Escherichia coli, Salmonella, and Shigella.

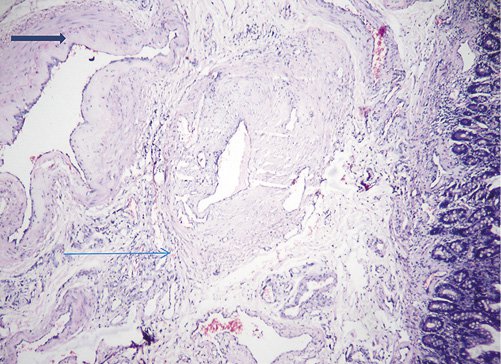

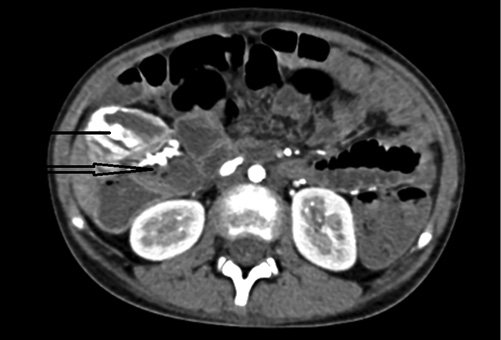

Meckel’s scan was negative. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen showed a contrast-enhanced small bowel segment with leash of vessels in the mesentery (Fig. 1). A provisional diagnosis of bowel AVM was made. After adequate resuscitation with packed red blood cell transfusion and following informed consent, the child was scheduled for surgery. At laparotomy, about 6 cm length of the Ileum, 12 cm from the ileocecal junction, was thickened with an “angry-red” appearance due to vessels on the serosa and prominent vessels draining the bowel segment into the mesentery (Fig. 2). Resection and anastomosis of the ileal segment was performed with an uneventful postoperative recovery. At the 6-month follow-up, she was doing well.

Fig. 1 Contrast-enhanced CT of the abdomen showing enhancement of the bowel wall (thin arrow) and leash of vessels (thick arrow).

Fig. 2 Intraoperative image of the ileal loop with “angry red” appearance (thin arrow) and blood within the lumen (thick arrow).

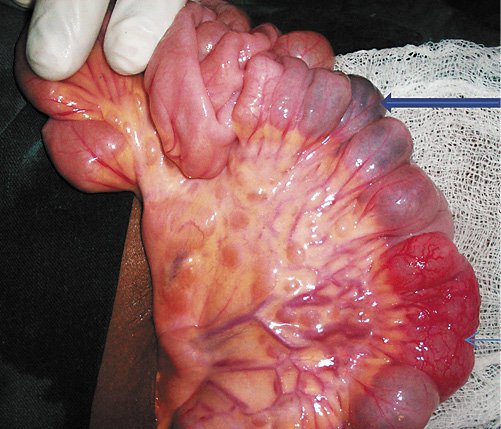

The presence of prominent and multiple vessels in the submucosa, with arteriolization of the vessel wall, led to the diagnosis of AVM of the ileum on histopathology (Fig. 3).

Discussion

Common causes of LGIB in a child include local conditions such as fissures, polyps, colitis, and Meckel’s diverticulum. Occasionally, unusual lesions such as GI duplication, AVM, and ectopic gastric mucosa can be a source for rectal bleeding. For the parents, such symptoms can be a source of considerable anxiety, especially when the bleeding is painless. On the other hand, when the clinical examination and investigations in a given child do not determine the potential cause of bleeding, the physician is under pressure to reach a diagnosis and to control the bouts of bleeding. Difficulty in diagnosis is registered when all imaging modalities fail to identify the malformation, leaving the physician in a desperate situation. This scenario is common in children with obscure LGIB (OGIB) due to bowel AVM [1, 2].

In cases of OGIB, capsule endoscopy can help to identify the source of bleeding in about 45-66% of patients [3]. A combination of single balloon enteroscopy with capsule endoscopy is expected to achieve improved diagnostic utility, although both techniques are simultaneously available in few selected centers [4].

Endoscopic interventions such as injection sclerotherapy, laser, and clips, for example, have a limited role in controlling OGIB [5]. Tagged RBC scan and selective angiography are other options to locate the source of bleeding [5]. Bowel AVM requires a high index of suspicion for diagnosis, as it is known to be associated with OGIB. In the event of all possible investigations not being able to locate the site and cause of bleeding, the next step would be to resort to an intraoperative enteroscopy combined with laparoscopy or laparotomy. Indocyanine green can help to locate a bowel lesion intraoperatively which was not identified by imaging [6].

Adult bowel AVM differs from that of a child. The colon is the common location in the adult, and often there is an association with cardiac disease and aortic stenosis. Syndromic lesions such as the Osler-Weber-Rendu syndrome, Klippel-Trénaunay syndrome, and blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome have a guarded prognosis as they are known to recur and run a protracted course [7]. Also, diffuse involvement of bowel precludes curative surgical excision. Nd YAG laser has limited application in cases where the mucosal vascular lesions are not amenable for surgical excision [8].

Conclusion

Although rare, painless bleeding per rectum with anemia in a child requires consideration of a surgical cause such as bowel AVM as a possible diagnosis. Contrast-enhanced CT can help identifying these uncommon lesions. Isolated bowel lesions are amenable for surgery and have an excellent prognosis.