Introduction

The vermiform appendix is described as “un organe inutile et nuisible” (French, a useless and a harmful organ). Acute appendicitis (AA) is a common disease, but infrequent appendix pathologies can also present with right iliac fossa (RIF) symptoms. Diverticular disease of the appendix (DDA) is one such pathology for which often the diagnosis is made after appendicectomy. DDA is rare, with an incidence of 0.004 to 2.1% in appendicectomy specimens [1]. DDA may be associated with or without AA, and the diverticula itself may be inflamed or non-inflamed. Clinical presentation of appendix diverticulitis is indistinguishable from AA [2]. Imaging features can distinguish appendix diverticulitis from AA, but histological examination remains a gold standard for diagnosis [3]. Owing to its rarity and lack of awareness related to its association with complicated AA, DDA remains underreported and poorly understood. Further, there is a minimal clinical incentive to invest efforts in studying DDA as eventual treatment is appendicectomy.

However, diagnosis of DDA may be relevant due to association with perforation or appendiceal neoplasms. Some reports suggest that patients with AA on a background of appendix diverticulitis are more likely to perforate, and DDA is associated with appendiceal neoplasms [4, 5]. In a retrospective Danish study including 4,413 appendix specimens from 2001-2010, Kallenbach et al. [6] reported that 39 patients had DDA and 4 (10.3%) patients had colorectal neoplasm. In a Spanish study reporting on 7,044 appendicectomies, Marcacuzco et al. [7] have shown a 46% association with perforation and 7.1% concomitant neoplasm incidence. They discuss the role of prophylactic appendicectomy in asymptomatic patients with an incidental diagnosis of DDA. In a retrospective report from the USA, Stockl et al. [8] observed association of DDA with Schwann cell proliferation (42%) and postulated that Schwann cell proliferation is a histologic harbinger of underlying DDA. In a Kuwaiti study over 8 years, Al-Brahim et al. [9] reported that none of the 25 patients with AD had associated neoplasm. Hence more data is needed to understand DDA with regards to its association with perforation and appendix neoplasms. We report our experience of DDA and validate association with complicated appendicitis or neoplasms. The secondary aim was to validate sepsis-3 criteria and quick Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment (qSOFA) scores in context of DDA.

Materials and Methods

A retrospective audit of appendicectomy histopathology reports from January 2011 to December 2015 was done. The list of patients who had appendicectomy was generated by accessing the International Classification of Diseases 9 and 10 codes of the hospital discharge database. All patients who had right hemicolectomy for primary colorectal malignancy or small bowel pathology were excluded. All listed histopathological reports were screened, and all patients with DDA reports were included.

Electronic medical records, operative records, and discharge summaries were reviewed for all DDA patients. Demographic and clinical data, including investigations, perioperative outcomes, 30-day mortality, and 30-day readmissions, were analyzed. Complicated appendicitis was defined as peritoneal abscess, free intraperitoneal air, perforation, or gangrenous appendicitis. Histology reports were reviewed for any form of malignancy. Modified Alvarado score, Andersson score, Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome (SIRS) criteria, and qSOFA scores were retrospectively calculated. All histology reports were reviewed to confirm a diagnosis of appendix neoplasm if any.

The Modified Alvarado score [10] is the most common clinical scoring system used in the diagnosis of AA and has a possible total of 10 points from eight variables, which consist of three symptoms (abdominal pain that migrates to the RIF, anorexia, and nausea or vomiting), three signs (tenderness in RIF, rebound tenderness, and pyrexia), and two laboratory tests (leucocytosis and left shift). Its diagnostic value is validated. The Andersson score [11, 12] was proposed as a diagnostic tool that outperforms the Modified Alvarado score, and it is computed from two symptoms (RIF pain and vomiting), two signs (rebound tenderness and fever), and three laboratory tests (leucocytosis, left shift, and C-reactive protein). The Andersson score can safely reduce the use of diagnostic imaging and hospital admissions in patients with suspicion of AA [11]. The SIRS refers to the clinical response to a non-specific insult of either infectious or non-infectious origin. SIRS criteria were established in 1992 as part of the American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine Consensus Conference [13]. It is defined by the presence of two or more variables out of four (temperature, heart rate, respiratory rate/PaCO2, and leucocytes). SIRS is highly sensitive for determining the severity of sepsis. The Sepsis-related (sequential) Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score is a mortality prediction tool that is based on six organ system dysfunctions: respiratory, cardiovascular, renal, coagulation, central nervous system, and liver function [14]. It is widely used in the intensive care setting. qSOFA score consists of three components, with one point each: respiratory rate >22/min (1 point), change in mental status (1 point), and systolic blood pressure <100 mm Hg (1 point), and a score of two or more indicates organ dysfunction.

Summary statistics were constructed for the baseline values, using frequencies and proportions for categorical data, and means for continuous variables. Length of stay is defined as the duration in days between the time of admission and time of discharge. Mortality is defined as death occurring within 30 days of surgery.

Results

During the study period, 2,305 appendicectomies were done. Histology established AA in 2,164 (93.9%) specimens, while 141 (6.1%) specimens had other pathology. A histologically normal appendix was noted in 110 (4.8%) specimens. Twenty-two patients (0.95%) had DDA, 6 (0.3%) patients had appendix endometriosis, and the appendix itself was absent in 3 (0.1%) specimens.

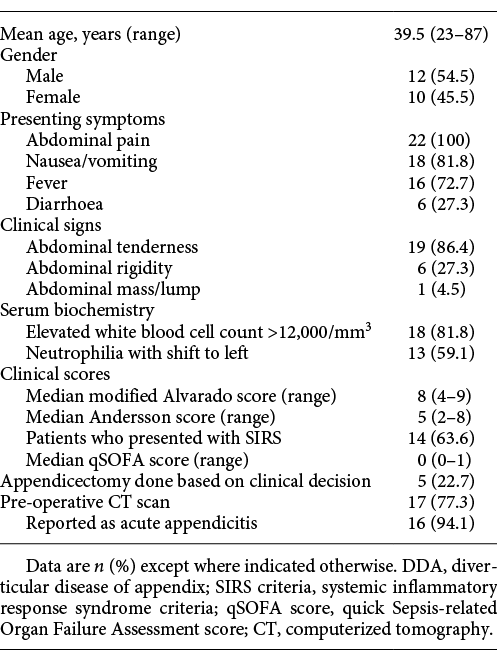

The mean age of patients with DDA was 39.5 years (range: 23-87 years). Appendix diverticulitis was noted in 10 (45.5%) patients. Table 1 demonstrates the demographic data and clinical profile of patients with DDA. Appendicectomy was performed based on admission clinical judgment in 5 (22.7%) patients, while computerized tomography (CT) scan was obtained in 17 (77.3%) patients. CT scan established diagnosis of AA in 16 patients, while one patient had a normal CT scan. In this patient, the decision for appendicectomy was based on clinical deterioration. Three patients (13.6%) underwent an interval appendicectomy - two (9.1%) patients for appendix phlegmon managed with antibiotics and one (4.5%) patient for peritoneal abscess drained percutaneously.

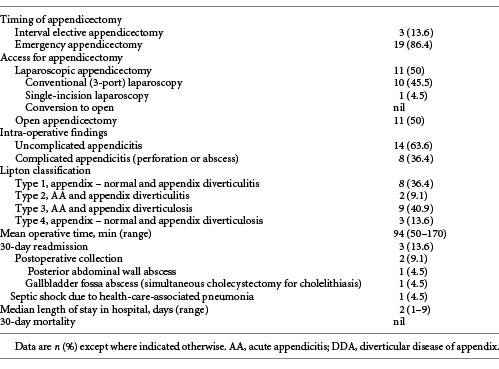

Table 2 shows the operative data and postoperative outcomes of patients with DDA. Eleven (50%) patients had laparoscopic appendicectomy, including one (4.5%) with single-incision laparoscopic appendicectomy. There were no conversions to open. Eight patients (36.4%) had complicated appendicitis. The mean operative time was 94 min (50-170 min), and the mean length of stay was 2 days (range: 1-9 days). Three (13.6%) patients had 30-day readmissions. Two (9.1%) patients had a postoperative abdominal collection. Of note, one of these patients developed the collection in the gallbladder fossa following synchronous appendicectomy and cholecystectomy (for symptomatic cholelithiasis). Both patients were discharged well after non-operative management with antibiotics and percutaneous drainage. The third patient was admitted for health-care-associated pneumonia. She was discharged well after treatment with antibiotics. There was no 30-day mortality.

Discussion

DDA is associated with older age and high incidence of complicated AA but not with neoplasms. Kelynack [15] first described appendix diverticulitis in 1893 in his thesis: “A contribution to the pathology of the vermiform appendix.” More than 125 years later, it remains uncommonly reported and poorly understood. The incidence of DDA in our experience (0.95%) is within the reported range of 0.004% to 2.1% [1]. Appendix diverticula may be either congenital (true) or acquired (pseudodiverticula), with the latter being more common. Congenital diverticula result from abnormal bowel recanalization during the intestine’s solid phase, compromises of all four layers of the bowel wall, found on the anti-mesenteric wall, and maybe single or multiple [16, 17]. They are associated with “D” trisomy or cystic fibrosis [18, 19]. None of our patients had “D” trisomy or cystic fibrosis. Acquired diverticula include only the mucosa or submucosa, are found in the mesenteric border, and may be single or multiple. Lipton et al. [20] classified DDA into four morphological types (Table 2) and also added subtypes according to the presence or absence of appendix perforation. AA with appendix diverticulosis (type 3) was most common in our experience.

Known risk factors for DDA are male gender, age over 30 years, Hirschsprung’s disease, and cystic fibrosis [18]. In a prospective observational study on AA, including 4,282 patients, Sartelli et al. [19] reported a median age of 29 years and 55% male gender. In our series, 54.5% were male, and the mean age of DDA was 39.5 years. In a retrospective study including 44 patients with appendix diverticulitis, Ito et al. [3] reported a median age of 59 years, which was higher than the median age of AA patients in their cohort. Thus, DDA is acquired and associated with old age, similar to diverticulosis disease of the colon.

With regards to symptoms, existing literature has a publication and reporting bias as only patients who had appendicectomy are included. Further, patients with right hemicolectomy for colon cancer are excluded. DDA can be asymptomatic and incidentally detected on radiological studies (e.g., barium enema). Clinical presentation of DDA and appendix diverticulitis mimics that of AA and varies from mild gastrointestinal disturbances to delayed presentation with an increased risk of perforation [20]. Ito et al. [3] reported that AD usually occurs in acquired diverticula containing only mucosa and submucosa and hence can easily perforate with peri-appendix abscess formation. Gomes et al. [21] proposed a grading system of AA based on complications. They included necrosis, phlegmon, abscess, and peritonitis as complicated AA. In our experience, DDA is associated with complicated appendicitis. A multicenter study, including 4,282 patients, reported 25.5% of patients with complicated AA as compared to this DDA study report of 36.4% [19]. Complicated AA is associated with delayed presentation or diagnosis and treatment. Delayed presentation is associated with inferior outcomes in acute care surgery [22-25]. However, the outcomes of DDA patients in our experience are not inferior. This is possible due to prompt resuscitation, adoption of sepsis guidelines, and timely multidisciplinary care [26-28]. It is not possible to derive conclusions about the clinical profile of DDA patients based on available literature. The reports on DDA either focus on imaging features or histopathology and lack clinical data [6, 29]. In a study including 1,329 patients with appendicectomy, Yardimci et al. [29] included 28 patients with appendix diverticulitis and reported on imaging features but not on clinical presentation or perioperative outcomes. In a study including 4,413 appendicectomy specimens, Kallenbach et al. [6] included 39 patients with DDA and reported on histopathology details but not on clinical presentation or perioperative outcomes. Thus, our study bridges the gap in the existing literature by reporting clinical profile, imaging, and histology of all the patients.

The pre-operative diagnosis of AD remains challenging due to various reasons. In some patients, the diagnosis of AA is made based on clinical judgment, and imaging is not done. In patients with imaging, the diverticula may not be seen due to a small size or involved by inflammatory mass [30]. Ultrasonographic findings include a hypoechoic lesion adjacent to the appendix suggestive of an inflamed diverticulum [31]. We do not do an ultrasound scan of the abdomen in patients with RIF pain due to the non-availability of ultrasound after office hours. Ito et al. [3] and Osada et al. [32] reported CT scan features compatible with appendix diverticulitis, such as rounded cystic appendix outpouchings with wall enhancement and solid enhancing masses emanating from the appendix. In our experience, pre-operative imaging did not contribute to the diagnosis of DDA.

The common complications of DDA include diverticulitis and perforation, which may lead to a localized abscess or generalized peritonitis. Lipton et al. [20] reported that appendix diverticulitis was four times as likely to perforate as AA, with a resultant increase in mortality [19]. More than a third of patients in our series had perforation, although there was no 30-day mortality. This could be attributed to early diagnosis, prompt resuscitation, and timely surgical intervention [33, 34]. All patients with AA are enrolled in the emergency waiting list, and they receive priority based on a physiologic insult. Our 30-day readmission rate of 13.6% is higher than reported by a recent multicenter study from the USA (6%) [35]. The association of DDA with complicated appendicitis is essential for the determination of the non-operative management of AA. Some studies have included such patients for non-operative management [36, 37], while some authors have excluded complicated appendicitis patients for non-operative management [38, 39]. It is our policy to reserve non-operative management to patients who refuse surgery, and our data exclude such patients. In our experience, SIRS criteria are more sensitive than qSOFA scores in patients with DDA. qSOFA score is reported to lack sensitivity in acute care surgery [24].

DDA has also been associated with pseudomyxoma peritonei [40] and appendiceal neoplasms like carcinoid tumors, mucinous adenomas, tubular adenomas, and primary appendiceal adenocarcinomas. Lamps et al. [41] found a 42% association between DDA and appendiceal mucinous neoplasms, while Dupre et al. [4] cited a 48% association between DDA and underlying appendiceal carcinoids and mucinous adenomas. None of our patients had any of the above associations, and it remains to be validated if such associations reflect diverse demography. Malignant lesions of the appendix are treated by right hemicolectomy, and it is possible that since we excluded right hemicolectomy specimens, our study is not able to detect such associations [34]. Rare complications of DDA include intestinal obstruction, hemorrhage, and fistula formation [42, 43]. Some authors advocate prophylactic appendicectomy when DDA is incidentally diagnosed during an unrelated surgical procedure in order to reduce complications or subsequent development of appendiceal neoplasms [7]. We did not study the colonoscopy database for lower gastrointestinal bleeding patients and hence were unable to comment association of DDA with bleeding. Our study has several limitations. This is a retrospective audit of patients treated with appendicectomy for clinically diagnosed AA. Due to the exclusion of patients managed with right hemicolectomy, the real association of DDA with malignancy remains unproven. Bleeding and inflammation of diverticular disease of the colon are distinct pathologies and mostly do not coexist. We did not study colonoscopy records or analyzed records of patients with a lower gastrointestinal bleed and hence were unable to detect a real association with bleeding. A large sample or prospective study, including all right hemicolectomy specimens, would provide more information about such associations. Due to lack of awareness of DDA and of little therapeutic importance, it is possible that pathology doctors may not actively look for and report DDA in appendix or right hemicolectomy histology specimens. Cadaveric dissection of subjects without AA and a histology review for the type of diverticulum is necessary to establish this entity. Lastly, due to small sample size we did not compare the results of uncomplicated with complicated AA for inflammatory scores.

In conclusion, DDA is a distinct clinical entity as it is associated with complicated appendicitis. Its association with appendiceal neoplasms is not observed due to the exclusion of right hemicolectomy specimens in our series. Existing reports selectively exclude the clinical profile of patients. qSOFA score lacks sensitivity in patients with DDA. More data is needed, and future reports must include right hemicolectomy specimens and report clinical profile and perioperative outcomes to enhance current evidence.