Introduction

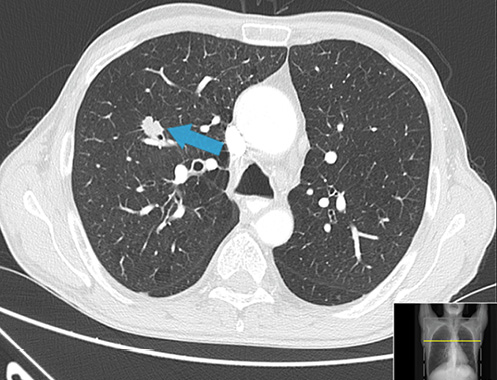

Strongyloidiasis is an infection caused by the helminth Strongyloides stercoralis, an intestinal nematode which is endemic in rural areas of tropical and subtropical regions of the world, particularly in hot and humid climates as well as countries with inadequate sanitary conditions, but it can also be transmitted in temperate regions such as North America and Southern Europe [1, 2] (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1: Map showing reports of the global prevalence of Strongyloides stercoralis infection in 2014 [1].

The global prevalence of strongyloidiasis is unknown, but experts estimate that there are between 30 and 100 million infected persons worldwide [3]. In Portugal there are no recent epidemiological data, but between 1914 and 1985 autochthonous cases of S. stercoralis infection were reported, suggesting endemic zones within the country in the past [4-6].

Distribution of S. stercoralis closely coincides with the geographic distributions of soil regimes, moisture, and temperature. The filariform larvae can survive with significant motility in water, greatly increasing their transmission potential. The most frequent mode of transmission is via skin contact with contaminated soil and poor water quality, which explains how the lack of adequate sanitation has a major influence, making strongyloidiasis a public health issue in these regions. Less common modes of transmission include fecal-oral transmission and person-to-person transmission via contact with fecally contaminated fomites.

The authors present a case of upper gastrointestinal bleeding with a challenging etiological diagnosis and propose to highlight an often-neglected parasitic disease.

Case Presentation

A 56-year-old Caucasian male, chronic smoker (63 pack-years), with a previously unremarkable medical history, complained of loss of appetite, postprandial fullness, epigastric discomfort, and a significant weight loss of 10 kg in the past year. The patient presented to the emergency room with hematemesis, dysphagia, and worsening of postprandial abdominal pain. Symptoms such as fever, diarrhea, or skin lesions were ruled out as well as journeys to tropical countries, rural areas, or contact with animals. The patient had not taken any medication, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory or immunosuppressive drugs.

On admission, the patient was hemodynamically stable and besides a mild epigastric pain without tenderness, physical examination was unremarkable. Intravenous treatment with high-dose bolus of proton pump inhibitor followed by continuous infusion was initiated. Laboratory tests showed normocytic normochromic anemia with Hb 9.8 g/dL (previous value 14 g/dL) and a significant elevation of inflammatory parameters with leukocytosis 21,230/µL (normal range: 4,000-11,000/µL), neutrophilia 84% without eosinophilia, increased C-reactive protein 29.3 mg/dL (normal range: <0.5 mg/dL), and erythrocyte sedimentation rate 120 mm/h, with a normal platelet count and INR. Subsequent laboratory examinations revealed iron deficiency (reduced serum iron 15 µg/dL and transferrin saturation 6%, with normal ferritin 194 ng/mL) and folic acid deficiency (plasma folate 1.8 ng/mL).

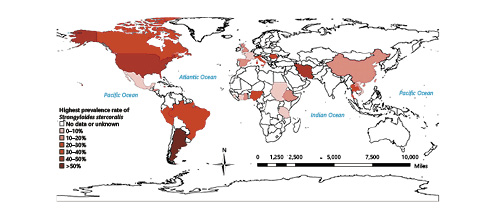

Upper endoscopy performed in the first 12 h revealed a giant gastric ulcer (30 mm) with regular borders and an adherent clot at the base - Forrest class IIb - comprising the distal third of the lesser curvature, extending through the anterior wall of the gastric body (Fig. 2); multiple biopsies were performed. The patient was discharged to outpatient consultation waiting for biopsy results and treated with pantoprazole 40 mg/day.

Fig. 2: Upper endoscopy showing a giant ulcer (30 mm) of the gastric antrum - Forrest class IIb. a Standard endoscopic view. b Narrow band imaging.

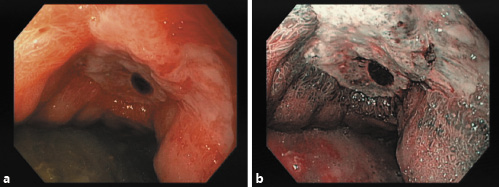

Given the macroscopic appearance of the gastric ulcer and the clinical presentation, neoplastic etiology was suspected, and a CT scan was performed highlighting gastric wall thickness, bronchiectasis, and a spiculated lung nodule with 16 mm in the upper right lobe, which was not previously known (Fig. 3). Imaging with both CT and PET scans excluded lymph node involvement or metastatic disease.

Bronchoscopy with bronchial brushing was performed and was positive for cancer cells, with histological examination revealing squamous cell carcinoma of the lung; the patient was referred to Oncological Pneumology. There was no evidence of filariform larvae in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid.

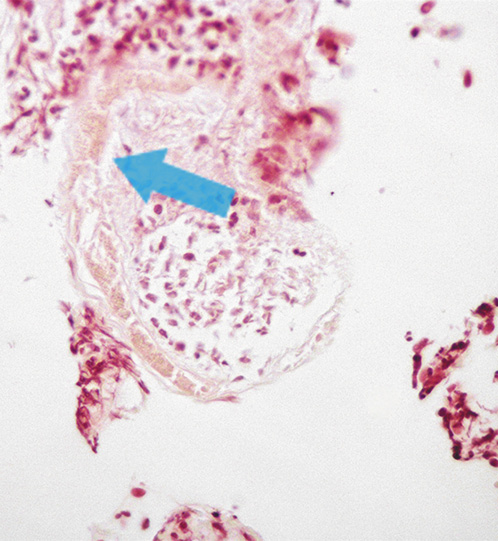

Four weeks later, despite treatment with pantoprazole, the patient complained of persisting abdominal pain. Evaluation of the gastric ulcer biopsies identified fragments of partially destroyed parasites with inflammatory infiltrates and fibrinogranulocytic exudate, indicative of S. stercoralis (Fig. 4). In the multiple biopsies evaluated there was no evidence of malignancy or Helicobacter pylori.

Fig. 4: Hematoxylin-eosin stain of the biopsy sample from the gastric ulcer showing a partially destroyed Strongyloides stercoralis nematode.

Considering the differential diagnosis of the gastric ulcer, in the absence of risk factors for stress ulcer and persisting pain despite proton pump inhibitors, with biopsies ruling out malignancy or H. pylori and having recognized S. stercoralis in the histopathological examination, the most likely etiological diagnosis was strongyloidiasis. Moreover, the patient had significant weight loss with folate and iron deficiencies representing a malabsorption state, which is a manifestation of strongyloidiasis. A PCR-based assay was performed in repeated stool samples and was positive for S. stercoralis.Serological tests using ELISA were positive and consistent with the diagnosis of strongyloidiasis. Treatment with ivermectin 200 μg/kg was administered on 2 consecutive days and pantoprazole was interrupted. On reevaluation 6 weeks after the ivermectin treatment, the patient was asymptomatic, had gained weight, folic acid and iron levels were within the normal range, parasitological stool examinations were negative, and the upper endoscopy showed complete ulcer healing. This significant improvement after ivermectin treatment is consistent with the etiology of the gastric ulcer being caused by the parasite.

Further tests were performed targeting risk factors for strongyloidiasis [7] considering the likelihood of immunosuppression in addition to the presence of malignancy. Laboratory tests including human T-lymphotropic virus type 1 (HTLV-1) and HIV 1/2 were negative and primary immunodeficiency was also ruled out.

Discussion

Gastrointestinal manifestations of strongyloidiasis typically include duodenitis induced by the adult worms, chronic enterocolitis, and malabsorption resulting from the high intestinal worm burden, while gastric involvement is very rare [8]. An underlying malignancy constitutes an impairment of the cell-mediated immunity which translates into an immunosuppressed state, having increased risk of developing a hyperinfection syndrome [9].

The diagnosis of strongyloidiasis is hampered by the lack of a gold standard as traditional parasitological tests including direct microscopic examination, although specific, have insufficient sensitivity. Hence, novel molecular methods have been implemented, using PCR to detect the DNA of the parasite, with the aim of achieving higher sensitivity and preserving the specificity for S. stercoralis infection, which ranges from 93 to 95% according to the reference test [10]. Other diagnostic tools include serological tests which have high diagnostic sensitivity and specificity and can be used as a screening tool for early detection. Several immunodiagnostic tests are available to identify anti-Strongyloides antibodies in serum, from which enzyme assays are recommended because of their greater sensitivity (>90%),but there are concerns about their specificity due to cross-reactions with other parasites and long-term persistence of antibodies after an effective treatment [11]. Eosinophilia typically associated with parasitic infections is often present but is not a reliable marker, and its absence does not exclude strongyloidiasis [12].

This case highlights the gastric involvement by strongyloidiasis, demonstrated by hematemesis due to a giant gastric ulcer in a patient who was subsequently diagnosed with early-stage lung cancer. Diagnosis of strongyloidiasis was made by microscopic examination and further confirmed with molecular methods and serology. The significant improvement after ivermectin treatment and without proton pump inhibitors suggests that the ulcer was induced by the parasite infection.

Regarding environmental factors, the adequate sanitation infrastructure in Portugal justifies that cases of strongyloidiasis are currently extremely rare. Nonetheless, reports suggesting endemic areas within the country in the last century makes one consider how many asymptomatic individuals might have S. stercoralis, which can remain quiescent in the host’s intestine for as long as 30 years. The advent of modern medicine with recognition of immunocompromised states, immunosuppressive treatment, cytostatic regimens, increased incidence of diabetes, cancer, and autoimmune diseases may result in strongyloidiasis reactivation and hyperinfection syndrome in those patients.

In conclusion, strongyloidiasis is an often-underdiagnosed parasitic disease due to its low parasitic load, irregular excretion of larvae, and nonspecific symptoms. Increasing diagnosis in developed countries and nonendemic regions may occur with globalization and transmission potential to immigrants, travelers, and immunosuppressed patients. Accordingly, as a key message, it is important that physicians consider this hypothesis in the differential diagnosis of cases in which diagnosis is unclear and have an integrated approach towards control of this parasitic disease.