Introduction

Neuroendocrine neoplasms (NENs) are rare neoplasms that arise from the neuroendocrine cell system. Previously described as carcinoids, this term is now reserved for metastatic NENs that produce the carcinoid syndrome [1]. Most NENs arise from the gastro-entero-pancreatic tract (GEP-NENs), i.e. from the stomach (23%), appendix (21%), small bowel (15%), and rectum (14%) [2].

GEP-NENs have a global annual age-adjusted incidence rate of 2.39/100,000 inhabitants per year [2]. The incidence is steadily increasing with a 6.4-fold increase from 1973 (1.09/100,000) to 2012 (6.98/100,000), across all sites, stages, and grades [3].

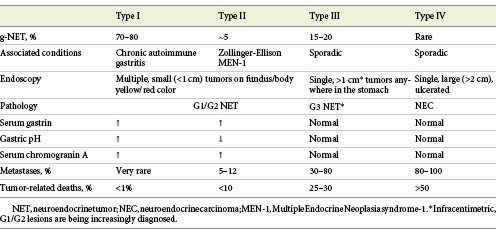

The World Health Organization (WHO) subclassifies NENs of the GI tract and hepatopancreatobiliary organs in order to reflect tumor biology, based on the mitotic count and Ki-67 index (Table 1) [4]. NENs are broadly classified as well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) and poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas (NECs), based on molecular differences - mutations in MEN1, DAXX and ATRX are entity-defining mutations for NETs while TP53 or RB1 mutations define NECs. Genomic data have also led to a change in the classification of mixed NENs. In 2019, the WHO updated its GEP-NEN classification, and a second change concerned the recognition that a small subset of high-grade NETs (G3) are histologically and genetically well differentiated and should no longer be included in the NECs category [4].

Table 1 2019 World Health Organization Classification of Neuroendocrine Neoplasms of the gastrointestinal tract and hepatopancreatobiliary organs [4]

Well-differentiated NETs are organized in rosettes, with a trabecular pattern that resembles enterochromaffin cells. In contrast, poorly differentiated NECs are high-grade carcinomas that resemble small cell carcinoma or large cell NEC of the lung [1]. Also, NENs should be staged according to a specific tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) staging, as proposed by the European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society (ENETS) [5]. These classification and staging systems are useful for guiding therapeutic decisions and establishing prognosis.

As previously stated, the incidence of GEP-NENs is steadily increasing, and one contributing factor seems to be the expanding indications of endoscopy. Therefore, endoscopists are in the first line of diagnosis of gastro-intestinal tract NETs (GI-NETs), predominantly gastric, duodenal and rectal lesions. When facing a lesion suspicious of a NET, the endoscopist should decide whether to biopsy or remove the lesion (and choose the resection technique), suggest/request adequate diagnostic and staging laboratory, and/or radiological exams. Although several national and international society guidelines have been published regarding the management of GI-NETs, we would like to emphasize that evidence on this topic is still scarce, and thus most of the recommendations are based on expert opinion. With this review, the authors aim to provide a practical and focused update on the management of well-differentiated NETs most frequently encountered in routine endoscopy. The management of poorly differentiated NECs and advanced disease is beyond the scope of this article and will not be addressed.

Gastric NETs

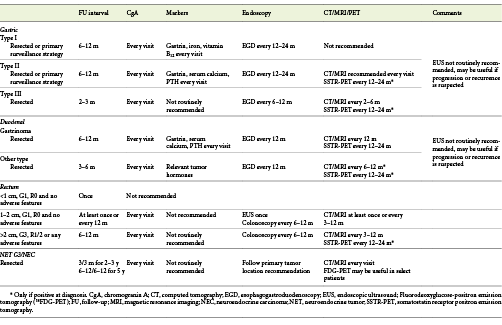

Gastric NETs (g-NETS) are the most frequent of all digestive NETs, representing up to 23% of the cases, with an annual age-adjusted incidence of 0.2/100,000 [2, 6]. g-NETs are further subclassified into subtypes based on clinicopathological characteristics, with important therapeutic and prognostic implications (Table 2) [1].

Type I g-NETs represent 70-80% of all g-NETS and are associated with advanced atrophic gastritis with corpus atrophy, more commonly with chronic autoimmune atrophic gastritis [6]. In this setting, compensatory hypergastrinemia induces proliferation of enterochromaffin-like (ECL) cells, hyperplasia, and, ultimately, NET [7]. They are more frequent in females and commonly associated with other autoimmune diseases (vitiligo, type 1 diabetes, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis) [6]. Most type I g-NETs are small (<1 cm), G1 tumors, limited to the mucosa or submucosa (SM) [8]. Lymph node metastasis (LNM) are detected in 2-9% of the tumors, particularly if greater than 1-2 cm, with muscularis propria (MP) invasion, or angioinvasion [9].

Type II g-NETs are rare, representing only 5-6% of g-NET cases, and commonly found in patients with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome (ZES) and MEN-1 (multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome-1), primarily caused by duodenal gastrinomas [8, 10]. The non-compensatory hypergastrinemia induces ECL-cells hyperplasia in the stomach, leading to the development of these tumors. Like type I, they are usually small, well-differentiated tumors with good prognosis [8]. However, LNM are found in 10-30% of the cases, especially if greater than 2 cm in size, MP invasion, or angioinvasion [9].

Type III g-NETs are sporadic tumors that account for 15-20% of g-NETs and are more frequently found in men with a median age of 50 years [8]. Most of these tumors are large (>1 cm), infiltrate the MP, show angioinvasion, and present with LNM (50-100%) at the time of the diagnosis [6, 9]. However, it should be stated that with the widespread use of endoscopy, small and low-grade type III g-NETs are being increasingly detected [11].

Type IV g-NENs were included in the classification to harbor the poorly differentiated NECs of the stomach. They are rare, sporadic tumors that typically present in elderly male patients [12]. They are the most aggressive type of g-NENs, and most of the patients have metastatic disease at diagnosis [1].

Clinical Presentation and Endoscopic Features

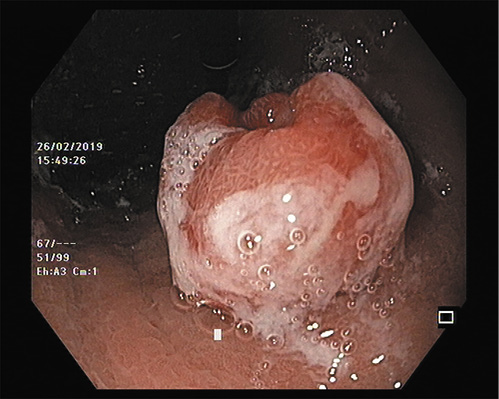

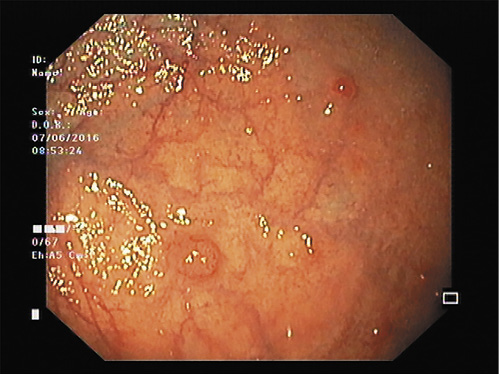

Most g-NETs, particularly in early forms, are incidental findings on endoscopy. Type I patients may present with dyspepsia or might be referred for anemia. Type II patients can present with abdominal pain and diarrhea as part of ZES, while type III/IV patients have a clinical presentation similar to gastric adenocarcinoma. On esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD), type I and type II are indistinguishable. They are usually multiple, small (<1-2 cm), yellow or reddish, polypoid, or submucosal lesions (with or without central depression or ulceration) more frequently found in the fundus and corpus [7] (Fig. 1). Abnormally reduced or flattened gastric folds suggest type I, while hypertrophic gastric folds and diffuse gastric and duodenal ulceration suggest type II. Narrow-band imaging (NBI) does not seem to add further information to the optical diagnosis. Indeed, in a recent study of patients with chronic gastritis under surveillance, even though g-NETs showed an abnormal mucosal pattern with NBI, no specific features were able to distinguish them from other intraepithelial lesions [13]. Therefore, biopsies should always be performed to confirm the optical diagnosis. Type III tumors are typically single and large (>1 cm), even though with the widespread practice of endoscopy, they are increasingly diagnosed at early stages and smaller sizes [9, 11] (Fig. 2). Type IV are often ulcerated, large lesions (5-7 cm) indistinguishable from adenocarcinomas [9].

Fig. 1 Multiple, small (<1-2 cm), reddish, polypoid lesion in the stomach corpus with surrounding atrophic mucosa suggestive of type I g-NET.

Diagnosis

If a g-NET is suspected on EGD, biopsy samples should be taken from the (largest) lesions and also from the antrum (at least two biopsies), body, and fundus (at least four biopsies) to confirm mucosal atrophy and H. pylori status [6]. It should also be noted that in the case of a few small lesions (<1 cm), direct polypectomy can be considered.

After histopathology confirmation, further laboratory tests are needed to assess subtype. All require measurement of serum gastrin and chromogranin A (CgA) [14]. Gastrin and CgA measurements should be performed at least 2 weeks after stopping proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), since they may be responsible for false positive results [1]. Assessment of anti-parietal cell and anti-intrinsic factor autoantibodies, as well as vitamin B12 and thyroid panel, also support type I diagnosis. The diagnosis of type II should also rely on clinical and family history and requires additional testing for serum parathyroid hormone and calcium. The diagnosis of type III/IV g-NETs is made when type I/II is excluded (Table 2) [8].

Staging

In type I g-NETs <1 cm, EGD is the only recommended procedure. In all g-NETs, if the tumor is ≥1 cm, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is recommended to evaluate the depth of invasion, LNM, and appropriateness for endoscopic resection (ER), although there are no large studies assessing EUS diagnostic yield [6, 15]. EUS can also be useful to assess the location of the gastrinoma in type II g-NETs.

Due to the indolent behavior of type I, further staging with computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and somatostatin receptor positron emission tomography (SSTR-PET) are seldom necessary unless there are signs of MP invasion or LNM on EUS evaluation [10]. In types II and III, further staging with CT/MRI and SSTR-PET is recommended [16, 17]. SSTR-PET is superior to both conventional imaging and SSTR scintigraphy for initial staging [17].

Management/Follow-Up/Prognosis

Treatment options depend on tumor type, size, and staging.

Type I

The prognosis of type I is excellent, with 5-year disease-specific survival higher than 95%. Recommendations vary slightly across European and North American Neuroendocrine Societies (ENETS and NANETS, respectively) (Table 2) [6, 16, 18]. According to both guidelines, tumors <1 cm should be offered surveillance and not ER, although a more aggressive approach with ER of all visible lesions (biopsy forceps/snare polypectomy for <5 mm and endoscopic mucosal resection, EMR, >5 mm) or ER of only larger lesions is also considered as an option in both guidelines [16, 18]. In larger lesions, recommendations differ between guidelines. ENETS recommends ER of all lesions ≥1 cm (without MP invasion), while NANETS recommends resection of lesions >2 cm but still consider endoscopic surveillance every 3 years as an option in lesions 1-2 cm without SM invasion (although resection should be preferred in case of SM invasion) [16, 18]. If we acknowledge the fact that the risk of metastatic disease has been associated with tumor size (cut off ≥1 cm), ENETs approach seems more reasonable [19].

ER consists of EMR or endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD), preferably by experienced endoscopists [18]. There are only a few case reports of device-assisted EMR for g-NETs published in the literature, with the largest studies concerning conventional EMR. There are also no large studies comparing conventional EMR and ESD. Only one small retrospective study has compared EMR and ESD in type I g-NETs but was restricted to <1 cm lesions [20]. In this study including 87 lesions, ESD achieved a higher but not statistically significant, complete pathological resection (CPR) rate (95 vs. 83%, p = 0.17) but at the cost of a higher but also non-significant complication rate (15 vs. 6%, p = 0.28 immediate bleeding, 3 vs. 0%, p = 0.44 perforation) and increased procedural time (26.1 ± 10.5 vs. 9.5 ± 3.6 min, p < 0.001) [20]. However, the goal of CPR rates in well-differentiated lesions may not even be significant regarding long-term outcomes. Indeed, Jung et al. [21] found no tumor recurrence during the follow-up (FU) in patients with NET G1/G2, even in patients with positive margins after ER (EMR or ESD). In fact, Uygun et al. [22] have reported 100% survival and disease-free rates during a median FU of 7 years after EMR of small, type I g-NETs. Therefore, for <1 cm tumors, EMR may be a better therapeutic approach.

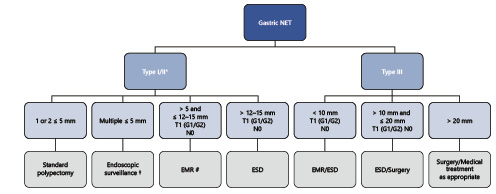

In our practice, after proper staging, we favor the following management (Fig. 3): for one or two≤5-mm lesions, ER with biopsy forceps or cold snare polypectomy instead of surveillance only since the risk of ER is very low and most of the times it is complete; for multiple≤5-mm lesions, we favor annual endoscopic surveillance (considering ER of NETs that show some irregular features); for 5- to 15-mm lesions, we prefer EMR over ESD since in most of these cases complete resection is possible and the clinical value of positive margins is not clearly determined; for >15-mm lesions, depressed morphology (IIc lesion), or atypical features, we tend to choose ESD to enable complete resection and proper histological staging.

Surgery should be limited to cases with invasion beyond SM, LNM, and G3 lesions [6]. Somatostatin analogs (SSAs) and netazepide may reduce tumor burden and progression, and they have been used to treat patients with multiple small lesions, although their role is not perfectly established [18].

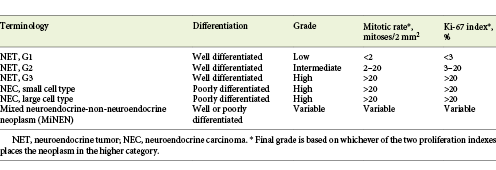

Type I g-NETs are recurring tumors due to persistent antral-mediated hypergastrinemia [23]. Regardless of resection, ENETS propose routine assessment of CgA, gastrin, iron, and vitamin B12 every 6-12 months and EGD every 12-24 months [24] (Table 3). At any surveillance, biopsies of new lesions should be performed [6].

Type II

Management is mainly influenced by the presence of concomitant duodenal or pancreatic NETs as part of the MEN-1 syndrome and requires a multidisciplinary decision. If indicated, according to ENETS, all lesions should be resected even in the presence of multiple lesions [6]. ER is indicated for all localized lesions and surgery for those with invasive or metastatic disease. NANETS, however, offers the possibility of surveillance in lesions smaller than 1 cm [16]. In addition, the resection of the co-existing gastrinomas should be attempted [8]. High-dose PPIs is recommended to suppress acid secretion and symptom relief in ZES.

The prognosis is good, with an associated mortality of less than 10% [6]. FU is identical to type I, with the exception that these patients may also benefit from additional CT/MRI every 6-12 months (Table 3) [24].

Our endoscopic management is similar to type I, with the exception that, whenever possible, we prefer ER of all visible tumors instead of surveillance, even for small tumors(Fig. 3).

Fig. 3 Summarized management of gastric NETs, according to authors’ own experience/preference. * The management of type II is similar to type I with the exception that we favor endoscopic resection of all visible tumors; † consider ER of NETs with atypical/irregular features; # or ESD if depressed/atypical features); NET, neuroendocrine tumor; EMR, endoscopic mucosal resection; ESD, endoscopic submucosal dissection; FTR, full-thickness resection.

Type III

The prognosis is poor, with a mortality rate of 25-30% and 5-year survival of 50% or less. Since the majority of patients present with large lesions, MP invasion, LNM, and angioinvasion at diagnosis, guidelines still recommend surgery (partial or total gastrectomy with lymph node dissection) as the preferred approach [6, 16, 18]. However, Kwon et al. [25] have demonstrated that ER can be safely performed in lesions <20 mm, G1, confined to mucosa/SM, and without lymphovascular invasion. In this study, 50 lesions were submitted to ER (41 by EMR and 9 by ESD) with 80% CPR rate. Incomplete resections due to lymphovascular invasion were submitted to additional surgery, while patients with margin invasion were followed up. During FU (median 44 months), there was no evidence of tumor recurrence or mortality in either the complete resection group or incomplete resection group [25]. ASGE also supports this approach, suggesting ER for isolated type III g-NETs <1 cm [26]. ENETS propose an intensive FU for type III g-NETs with biochemical and imaging studies every 2-3 months and EGD every 6-12 months (Table 3) [18].

From our experience, after proper staging, we suggest the following management (Fig. 3): for lesions≤1 cm and no evidence of LNM, ER (EMR or ESD) is preferred over surgery (even though this is always discussed with the patient) to allow proper histological staging and eventually curative resection; for lesions between >1 and≤2 cm and no evidence of MP invasion or LNM, we favor ER by ESD over surgery to allow proper histological staging (except in the young and fit patient where surgery is also first line); for lesions >2 cm, ER should not be an option and surgical and/or medical treatment should be offered to these patients.

Type IV

Type IV g-NETs have an extremely poor prognosis with a 50% mortality rate at 1 year. ER is not adequate for NEC even in the rare cases of a T1 tumor [9]. If the disease is localized, surgery may be indicated, while in patients with advanced disease, systemic therapy is advised [9].

Overall, after ER of g-NETs, surgical treatment should be considered if lymphovascular invasion, G3 grading, or MP invasion. If positive margins, we typically schedule additional ER in 3-6 months and only consider surgery if recurrence not amenable to further ER or in type III tumors.

Duodenal NETs

Duodenal NETs (d-NETs) are rare, accounting for 2.8% of all NETs with an annual age-adjusted incidence of 0.19/100,000 [27, 28], and are more common after 50 years of age, with a slight male predominance [27].

Duodenal NENs comprise mainly gastrinomas, somatostatinomas, non-functional tumors (that may stain for calcitonin and serotonin), duodenal gangliocytic paragangliomas, and high-grade poorly differentiated NECs [6]. Overall, most of d-NENs are non-functional, well-differentiated, located in the proximal duodenum, and rarely present with local or distant metastasis at diagnosis (less than 10%) [27, 29]. Functional d-NENs (e.g., ZES in gastrinomas) have a high risk of metastatic disease at presentation even if small size and will not be discussed in detail [12].

d-NETs of the ampullary region (20%) have a different biological behavior when compared with d-NETs located elsewhere, bearing a higher likelihood of LNM at presentation even with small sizes [30].

Clinical Presentation and Endoscopic Features

The majority of patients are diagnosed incidentally during EGD. Rare presentations include symptoms related to functioning tumors like ZES [6]. On EGD, d-NETs are typically single, small (mean size 1.5 cm), sessile, pale, or reddish lesions found in the duodenal cap or bulb [10]. As the tumor grows, a depression may form in the center, which is eventually replaced by an ulcer crater [31]. To date, there have been no studies concerning the role of NBI to aid in the optical diagnosis.

In the case of gastrinomas, multiple gastric and duodenal ulceration or severe reflux esophagitis may also be found. Also, multiple d-NETs or the concomitant presence of g-NETs should raise the suspicion of MEN-1.

Diagnosis and Staging

EGD with biopsy is the most sensitive modality for the diagnosis [6]. EUS with fine needle aspiration should also be performed in cases of non-diagnostic histopathology, for local staging (tumor invasion and LN metastasis) prior to ER, and in patients with MEN-1 with the additional ability to assess the pancreas for pancreatic gastrinomas [15]. CT/MRI and PET-CT are also indicated. If liver metastases are detected, further MRI of the spine and bone scintigraphy should be performed [6].

According to ENETS, all patients should have serum CgA levels determined. Determination of additional serum hormones should be performed if suggested by the clinical picture or positive immunohistochemistry [6].

Management

Management is based on tumor size, location, histological grade, stage, and tumor type.

Ampullary d-NETs

Pancreatoduodenectomy has been recommended for resectable ampullary d-NETs regardless of size, due to a relatively high risk of occult LNM [18]. However, these recommendations were based on small case series, and treatment decisions should be individualized based on precise tumor location, histological grade, depth of invasion, and patient suitability for aggressive surgery. In one of the largest studies of ER of d-NETs (only EMR), which included 7 ampullary G1/G2 NETs with ≤20 mm, without MP invasion or LNM, CPR was achieved in 5 patients (71%). On FU, no patient in the CPR group presented recurrence, while 1 patient in the incomplete resection group presented with LNM [32]. The overall complication rate was 34%, with 3% procedure-related death. The majority of complications included intraprocedural bleeding, controlled with further endoscopic treatment [32]. However, if we take into account the significant morbidity and mortality rates of a pancreatoduodenectomy, ER may be a more reasonable alternative in selected patients.

Non-Ampullary d-NETs

Small (≤1 cm) G1/G2 d-NETs without local or distant metastases are eligible for ER. Several ER methods have been proposed, including ESD, EMR, EMR with ligation devices, hybrid-EMR, underwater submucosal resection, endoscopic full-thickness resection (EFTR), and recently endoscopic banding without resection [33-40].

In small d-NETs, Kim et al. [33] have reported a CPR rate of 100% (4/4), with no recurrence at a mean FU of 17 months after ER. ESD had a higher rate of minorintra-procedural bleeding (75 vs. 6%), and longer procedure time (average 33 vs. 13 min) when compared to EMR [33]. In two small series by Matsumoto et al. [34] and Suzuki et al. [35], the perforation rate with ESD was exceedingly high (2/5 and 2/3, respectively).

With EMR and EMR-based techniques (band ligation and circumferential precutting), the procedure time is shorter, with fewer complications and with complete ER rates that range from 89 to 100%. Even though CPR rates were lower, ranging from 25 to 56%, if endoscopic complete resection was achieved and the invasion depth was limited to the SM, recurrence was not observed during the FU assessments [33].

In a recent review of 15 duodenal lesions resected with EFTR, the CPR rate was 93%, with a complication rate of 27% (3 micro-perforations and 1 perforation) [41].

Overall, the majority of these studies are small, non-controlled retrospective case series, case reports with a paucity of data regarding long-term outcomes. Therefore, the ER method should be chosen according to tumor location, shape, size, and, most importantly, endoscopist expertise.

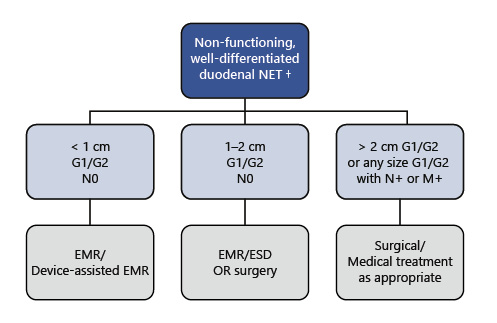

In our practice (even though we have ESD experience), EMR based techniques are preferred whenever possible for small (<1 cm) d-NETs, most of the times allowing a complete and safer resection(Fig. 4).

Fig. 4 Summarized management of non-functioning duodenal NETs, according to authors’ own experience/preference. † If periampullary location, surgical resection is recommended regardless of size; endoscopic resection may be performed in very selected cases. NET, neuroendocrine tumor; EMR, endoscopic mucosal resection; ESD, endoscopic submucosal dissection.

Large (≥2 cm), G1/G2 d-NETs without metastases should be surgically resected as well as d-NETs of any size with LN metastases [6].

The management (ER vs. surgery) for intermediate size d-NENs (1-2 cm), G1/G2 d-NETs without metastases is still not standardized [18]. Even though most may be endoscopically resected, the risk of LNM is considerable, and a decision should be made on a case-by-case scenario [12].

In these cases, we consider ER only when the location of the tumor may imply a more aggressive surgery and/or when the patient is less fit for surgery(Fig. 4).

G3 tumors and poorly differentiated NEC require oncological surgical resection with adjuvant chemotherapy [6].

For the minority of patients with a functional clinical syndrome (10%), oncological surgical resection if resectable and appropriate specific therapy are indicated (e.g., PPIs in ZES, SSAs in carcinoid syndrome) [6].

FU and Prognosis

The prognosis is dependent on size, grade, and functionality. Overall, patients with non-functioning d-NETs have a fare better outcome, and patients with high-grade d-NETs have a worse outcome than adenocarcinoma [42].

Non-functional d-NETs should be followed every 6-12 months with CgA and relevant tumor hormones and yearly EGD and imaging studies (Table 3) [24].

Rectal NETs

Rectal NETs (r-NETs) have an annual age-adjusted incidence of 0,86/100,000 in the United States. r-NETs represent 27% of gastrointestinal NETs overall, with higher rates (>60-80%) being reported in Japanese and South Asian populations [27, 28, 43]. There is a male predominance, and the mean age at diagnosis is 57 years [27].

Most r-NETs arise from L-cells and are characterized by the production of glucagon-like peptide, pancreatic polypeptide, and peptide YY. Most tumors are small (<10 mm) and grade G1/G2 [44, 45]. Local and/or distant metastasis are present at diagnosis in 3, 66, and 73% of tumors measuring ≤10, 11-19, and ≥20 mm, respectively [46].

Clinical Presentation and Endoscopic Features

The majority of patients are asymptomatic, and lesions are found during screening colonoscopy [46]. On endoscopy, r-NETs are generally small (<1 cm in 85% of cases), smooth, round, mobile, yellowish submucosal lesions with a reddish tinge, significant microvessel density, sometimes with a central punctum and found between 5-10 cm of the anal verge in 87% of the cases [47]. Atypical findings include a semipedunculated shape (10%), erosion (8%), and ulceration (6%). These atypical forms seem to predict a more aggressive form of disease [47]. In the only case report where r-NET is described under magnifying NBI, it showed small round pits, surrounded by brown, honeycomb-like microvessels [48].

Diagnosis and Staging

The majority of r-NETs are diagnosed endoscopically. In some cases, r-NET resemble epithelial polyps, are removed in index endoscopy, and the diagnosis is only made after histopathological analysis [44]. However, it should be stated that an ER in index colonoscopy should not be pursued if any high-risk stigmata (i.e., atypical features, >10 mm) are present due to the higher risk of invasion and metastases. Therefore, biopsy should be taken for histological confirmation in suspected r-NETs over 5 mm and/or high-risk stigmata, while EMR may be performed in smaller lesions at index colonoscopy [23]. Also, a full colonoscopy is required at some point, as part of staging, and to exclude synchronous carcinoma [44].

EUS is recommended in all lesions >5-10 mm or with atypical features to assess depth of invasion and the presence of LNM [15, 23, 44]. A small study on the use of EUS in 22 rectal NENs showed a 100% accuracy for EUS in assessing invasion depth before ESD [49].

Additional imaging includes a thoracic, abdomen, and pelvic CT in patients with lesions >1 cm and when LNM are detected, to assess for distant metastasis [44]. MRI of the pelvis is also indicated for r-NETs with size >2 cm, with MP invasion or beyond or with LNM [44]. MRI of the pelvis is also required after an incomplete resection to assess for invasion, stage, and predict resection margins [44]. For well-differentiated r-NETs with >2 cm or MP invasion or LNM, SSTR-PET is useful for detecting metastatic lesions. Fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography (18FDG-PET) is preferable in poorly differentiated r-NETs since they may not express somatostatin receptors [44]. Minimum laboratory studies include serum CgA determination [44].

Management

Like other NETs, management depends on size, grade, and staging. Also, evidence is substantiated mostly on single-center studies with small groups of patients.

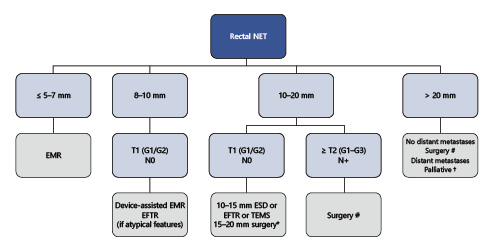

As previously stated, lesions <5 mm have a very low probability of invasion beyond the MP and can be resected on index colonoscopy [23]. Lesions G1/G2 5-20 mm may also be amenable for ER after adequate staging [44]. As with other GI-NET, several ER methods have been proposed. However, it should be underlined that standard polypectomy is not recommended since complete resection rates are as low as 17% [45, 50]. If an attempt at resection is performed at the index colonoscopy using suboptimal techniques and resection margins are involved, an endoscopic assessment of the scar site is required, and proper staging should be performed. Further salvage ER may be indicated.

In r-NETs <1 cm, complete resection rates seem superior in device-assisted EMR versus conventional EMR. Yang et al. [51] compared conventional EMR, cap-assisted EMR, and ESD in 138 <10 mm r-NETs and reported a higher complete resection rate with cap-assisted EMR (94 vs. 77% in conventional EMR, p < 0.032), with a tendency for more intraprocedural bleeding (8.8 vs. 0%, p = 0.051). Another prospective study showed similar complete resection rates in 66 r-NET <10mm with EMR and ESD (82.8 vs. 80.6%, p = 0.8), with the advantage of lower procedure duration with EMR banding [52].

For lesions 1-2 cm, ESD has the advantage of higher en bloc and complete resection rates. In a retrospective study by Chen et al. [53] including 239 colorectal NETs (98% rectal), CPR rate was 92% for NETs <1 cm and 85% for NETs 1-1.9 cm. In 8 cases (3.4%), there was a complication, namely bleeding in 6 cases and perforation in 2 cases.

It should also be noted that incomplete resection of r-NETS does not preclude endoscopic salvage resection [23]. Reported salvage therapies include device-assisted EMR, ablation, ESD, and local surgical excision [54-56]. According to ENETS, if EMR leads to incomplete resection, ESD or transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEMS) may be indicated, without evidence to support one over another [45]. Recent techniques such as EFTR also play a role as salvage therapy or even as primary ER in r-NETs with 10-20 mm or G2 grading, as was recently demonstrated by Meier et al. [57].

TEMS may also be considered as a primary resection method for r-NETs 1-2 cm, G1-G2, confined to the SM or small-sized r-NETs (<1 cm), G2-G3, with MP invasion but without LNM [44]. Rectal tumors >2 cm, between 1-2 cm with MP invasion, T3-T4 stage, G3 grading, or lymph node involvement should be treated with rectal anterior resection or abdominoperineal resection if in the lower rectum [44].

From our experience, most r-NET≤5-7 mm can be safely and completely removed by standard EMR. For tumors 8-10 mm, we prefer device-assisted EMR or ESD/EFTR if the tumor presents depressed morphology (0-IIc). However, for tumors 10-15 mm, surgery is always discussed with the patient, but if staging procedures exclude MP involvement and LNM, we prefer ESD or EFTR over EMR to allow safer margins and proper histological diagnosis. For tumors 15-20 mm, even when staging procedures do not show LNM, surgery is our preferred approach since the risk of microscopic LNM is substantial in these cases. If the patient refuses or is less fit for surgery, we prefer ESD or TEMS over other methods. In the common scenario of a patient with a previously resected <10-mm polyp that showed to be a G1/G2 NET with positive margins (without other risk features), we repeat endoscopy at 3 months. If the scar does not show macroscopic recurrence/residual tumor, we always perform biopsies, and if the scar shows residual tumor, we prefer EMR based techniques or ESD/EFTR (depending on recurrence characteristics, namely depending on adequate elevation of the lesion) instead of avulsion methods, in order to allow complete resection of that area and also histological diagnosis (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5 Summarized management of rectal NETs, according to authors’ own experience/preference. * ESD, EFTR, or TEMS alternative if no muscular invasion and patient refuses major surgery; # anterior resection + total mesorectal excision or abdominoperineal resection; † surgery/stent/chemotherapy. EMR, endoscopic mucosal resection; ESD, endoscopic submucosal dissection; EFTR, endoscopic full-thickness resection; TEMS, transanal endoscopic microsurgery.

FU and Prognosis

According to ENETS, completely resected tumors with <1 cm, G1-G2 grading, with no MP invasion or LNM, do not require regular FU [18, 24]. Additional FU for other tumors is presented in Table 3.

R-NETs have the best overall survival of all GI-NETs largely due to the high incidence of small lesions without evidence of invasion. Tumor stage at diagnosis is the most important prognostic factor. Localized T1 r-NETs have a 5-year survival of 98-100%, while those with regional and distant metastases have a 54-74 and 15-37% survival, respectively [23].

Conclusion

GI-NETs are increasing in incidence, in part due to expanding indications for endoscopy, so endoscopists need to be aware of specific characteristics regarding diagnosis, staging, and management. ER is a cornerstone of the management of these tumors, and the endoscopist should be familiarized with different technique modalities in order to maximize resection rates and long-term outcomes. Also, we would like to point out that multidisciplinary collaborations are essential for the diagnosis and management of these tumors and that prospective institutional and national registries and consortiums would allow research progress for the optimal management of NETs in the future.