Introduction

Liver cancer is the fifth most common and the second most frequent cause of cancer-related death globally. Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) represents around 90% of all primary liver cancers [1]. Unlike HCC, cardiac tumors are a rare entity [2]; they are classified into primary and secondary. Primary cardiac tumors include all benign or malignant neoplasms arising from any heart tissue. Secondary tumors are much more common, with an incidence ranging from 2.3 to 18.3% [3]. Although any malignant tumor can metastasize to the heart, the most common are lung, breast, melanoma, pleural mesothelioma, and hematological cancers [4]; tumor invasion can occur through multiple mechanisms, including hematological, lymphatic, vascular, or direct invasion. HCC often metastasizes to bone, lungs, lymph nodes, and adrenal glands. Despite its proximity to the heart and vascular invasion potential, intracardiac metastasis are a rare manifestation of the disease. Prompt diagnosis is essential as they can cause heart failure or even sudden death.

Case Presentation

A 65-year-old male patient regularly followed in the hepatology clinic due to chronic hepatitis B (with DNA levels <2,000 IU/mL) and alcoholic cirrhosis (with previous surveillance abdominal ultrasound 8 months before showing cirrhotic liver without focal lesions), presented to the emergency department with a 1-month history of anorexia, nausea, weight loss, associated with mild exertional dyspnea, abdominal distention, and bilateral lower extremity swelling. At physical examination, the patient was hemodynamically stable (blood pressure of 110/70 mm Hg, heart rate 78 beats/min); cardiac examination revealed regular heart sounds without murmurs; abdomen with tense ascites; presence of bilateral lower limb edema. There was no jugular venous distension, and lungs were clear to auscultation. Initial laboratory findings showed normal hemoglobin and leucocyte count, with mild thrombocytopenia (97 × 103/µL, normal range 150-350); INR was normal (1.1, range 0.8-1.2); liver function tests had a small elevation of aspartate aminotransferase (52 U/L, normal range 5-34), a slight elevation of the bilirubin level (1.98 mg/dL, normal range <1.2), and a significant elevation of γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (437 U/L, normal range 12-64) and C-reactive protein (11 mg/dL, normal range <0.5). N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) was slightly elevated (1,415, inclusion level >900). Diagnostic paracentesis excluded spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. The electrocardiogram displayed normal sinus rhythm. Urgent transthoracic echocardiogram revealed a mass with 35 × 30 mm in the right atrium (RA). He was admitted for further investigation and management.

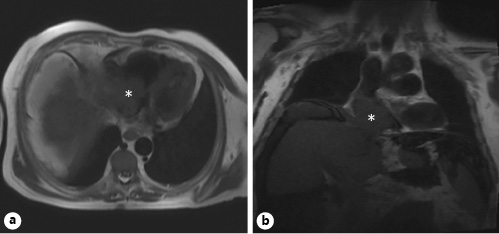

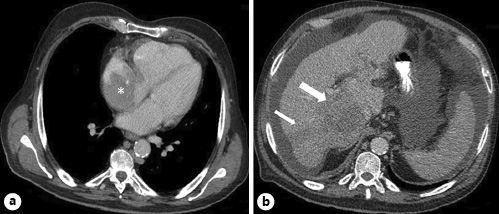

Subsequent chest, abdominal, and pelvic computed tomography revealed a large mass measuring 70 × 30 mm, occupying most of the RA; the abdomen presented large-volume ascites and heterogeneous liver with multiple nodular lesions on the right lobe suggestive of malignancy (Fig. 1); there was no evidence of pulmonary embolism or secondary lesions. The alpha-fetoprotein dosing was 14,541 ng/mL (normal range <8). A cardiac magnetic resonance confirmed previous findings, showing the cardiac mass was extending from the liver through the inferior vena cava (IVC), occupying the majority of the RA (Fig. 2). A transjugular biopsy of the cardiac mass confirmed the diagnosis of HCC. Due to the worsening of his clinical condition and the IVC occlusion, maintaining right heart failure symptoms despite optimized medical therapy, the patient underwent surgical treatment to remove the cardiac tumor. The postoperative course was complicated by septic shock caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae infection; despite treatment with broad-spectrum antibiotics, ventilatory and aminergic support, the patient died on the 30th day after surgery.

Fig. 1 Computed tomography of the chest (a) revealing a large mass in the RA (asterisk), and abdomen (b) presenting multiple nodular lesions on the right lobe of the liver (arrows).

Discussion

With 854.000 new cases of liver cancer and 810.000 related deaths globally in 2015, HCC is a common malignancy with growing incidence [5]. The recognized risk factors for HCC include alcohol-induced cirrhosis, chronic hepatitis B virus, and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, exposure to dietary aflatoxin, fatty liver disease, obesity, smoking, diabetes, and iron overload [6]. Regardless of its etiology, cirrhosis is a major risk factor for HCC, with approximately 1-8% of all cirrhotic patients developing HCC per year [1].

Unlike most solid cancers, the diagnosis of HCC can be established using noninvasive imaging methods without biopsy confirmation; alpha-fetoprotein and other serum biomarkers usually have a minor diagnostic role [7]. It is a clinically silent and aggressive entity, as only 30-40% of the patients are suitable for curative treatment at diagnosis [8]. Being a highly vascular tumor with intravascular dissemination, it presents a high incidence of portal and hepatic veins thrombosis at 20-65 and 12-54%, respectively [9, 10]. In some cases, tumor thrombus can grow from the HVs through the IVC into the RA; this is a rare situation, with a reported incidence of 1-4% [11]. Most of the cardiac metastases are direct and contiguous extensions of intrahepatic tumors; isolated cardiac metastases of HCC are extremely rare [12]. A study by Jun CH et al. [13] identified some risk factors for RA extension in a cohort of 665 patients diagnosed with HCC (33 with RA invasion), namely a modified TNM staging classification ≥IVa, hepatic vein invasion, concomitant PV and IVC invasion, and multinodular HCC. The initial investigation of choice to detect cardiac metastasis is two-dimensional transthoracic echocardiography, as it is noninvasive and both pericardial involvement and intra-cavitary lesions can be detected with high sensitivity [14].

HCC with IVC and cardiac extension is associated with a higher risk for cardiopulmonary complications, with heart failure or sudden death as the cause of death in 25% of the patients [15]; other possible complications include tricuspid stenosis or insufficiency, ventricular outflow obstruction, cardiac arrhythmias, pulmonary embolism and pulmonary metastasis. Regarding symptoms, there is a wide variety of clinical manifestations, which are mainly tumor size dependent. In a study by Liu et al. [16] including 48 HCC patients with cardiac metastasis, most patients were asymptomatic (39.5%); main symptoms were bilateral lower limb edema (37.5%), exertional dyspnea (31.3%), chest pain (8.3%), syncope (2.1%), and hypotension (2.1%). Overall, patients may be asymptomatic or present with non-specific symptoms such as dyspnea, chest pain, pre-syncope or syncope, cough, fever and/or hemoptysis. Physical findings include peripheral edema, systolic murmur with diastolic rumble over the tricuspid valve, and improvement of symptoms with left lateral decubitus [17].

Advanced HCC has a poor prognosis, with a reported median survival of 4-7 months in untreated patients [18]; prognosis of HCC with RA invasion is even worse, with a life expectancy of 1-4 months [19]. Currently, there are no guidelines on the management of HCC with RA extension. Therapeutic options include palliative surgery, chemotherapy (either systemic or local), and radiation. Given that surgery to remove intracardiac mass combined with hepatectomy is the only radical treatment that may offer a chance of complete tumor removal, it has been attempted in some cases. Wang et al. [20], in a cohort of 56 patients with RA invasion by HCC, reported that prognosis following surgery was significantly better than that achieved by transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) or no treatment, suggesting that in selected patients surgical treatment may be a valid option. For those who are not candidates for surgery, both systemic and local chemotherapies have been used. Sorafenib, a multi-target tyrosine kinase inhibitor, has been shown to improve overall survival in advanced HCC [21]. TACE has also been attempted; Chern et al. [22], in a cohort of 26 patients with IVC invasion (and RA extension in 5), demonstrated that those who responded to TACE had better overall survival than non-responders.

In conclusion, cardiac metastases are an uncommon entity associated with several malignancies, including rare cases of HCC. Early diagnosis of HCC is essential to prevent cardiac presentation. Clinical suspicion should be kept in any cirrhotic patient who presents with new-onset symptoms of right heart failure, as described in our case. Despite a poor prognosis, early diagnosis may allow prompt initiation of treatment, which should be multidisciplinary and individualized, aiming to improve quality of life.