Introduction

Radiotherapy (RT) takes part in the management of prostate adenocarcinoma [1]. Advances in radiation delivery and imaging have triggered the development of targeted, high-dose radiotherapy (IMRT). However, rectal toxicity may restrain RT due to the rectum and prostate-close anatomy [2]. In the acute setting, radiation can cause ulceration and rectal edema. Chronic radiation proctitis can continue from the acute phase or reoccur, resulting in ischemia [1]. Argon plasma coagulation is the utmost endoscopic management of bleeding radiation proctitis. However, repetitive applications are required, it has little effect on urgency or incontinence, and it is not without complications. Additionally, hyperbaric oxygen therapy is emerging but it is not widely available, and surgery conveys a significant risk of iatrogenic injuries [1]. Apart from higher dose and larger radiation fields, other risk factors for rectal toxicity are non-modifiable: history of abdominal surgery; collagen disease; age; diabetes, hemorrhoids, and inflammatory bowel disease [2]. A spacer placed between the prostate and the rectum can be used to displace it from the high-dose zone [3]. Biodegradable spacers, including hydrogel, hyaluronic acid, collagen or an implantable balloon, can be placed in an easy manner. Overall, these spacers have an excellent safety profile and placement is well-tolerated [4]. As for balloon spacers in particular, they were created to be transperineally implanted, guided by transrectal ultrasound, within the prostate-rectum interspace, in the Denonvilliers’ fascia. After positioning the insertion spacer, the balloon is filled with sterile saline. The procedure may be performed by an expert, under local anesthesia [5]. The system stays inflated during the full treatment period and posteriorly biodegrades [6]. Few and rare complications have been documented in addition to perianal discomfort during placement [7].

Case Presentation

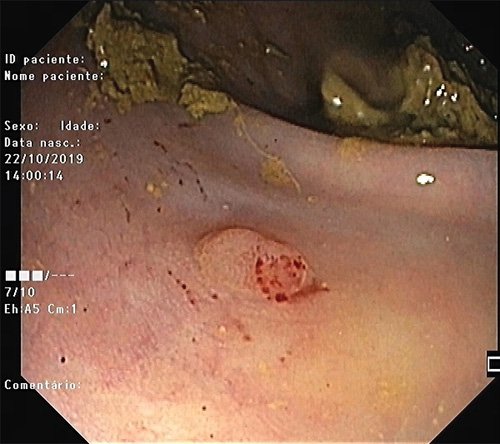

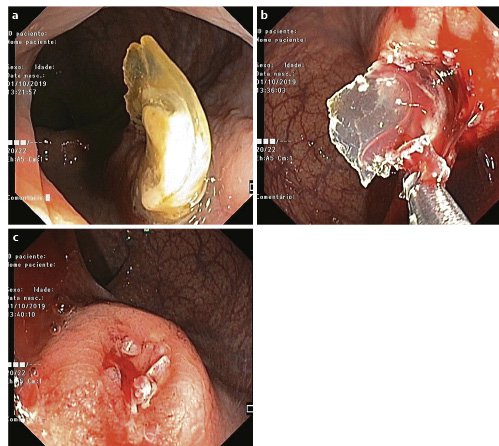

We report the case of a 59-year-old man with a diagnosis of prostate adenocarcinoma (cT2N0M0, stage IIIC), proposed to complete hormonal treatment followed by IMRT. In order to minimize rectal irradiation, an ultrasound-guided balloon spacer (BioProtect®) was implanted using blunt dissection. One month after the device placement, the patient presented with a 3-day persistent rectal bleeding. A digital rectal examination identified a flexible foreign body that appeared to be in continuity with the anterior rectal wall. A sigmoidoscopy showed a partly implanted foreign body in the rectal wall, above the dentate line, compatible with a rectal perforation by the spacer. Cautious removal was carried out on several fragments with biopsy forceps and a polypectomy snare (Fig. 1). After extraction, a small fistula orifice was observed, with no complication signs, and so, fistula closure was not attempted and no antibiotics were given. Two weeks later, a follow-up endoscopy was performed showing only a small papule, without fistula or ulceration (Fig. 2). Afterwards, the patient started IMRT without a spacer system. At the end of the treatment, the patient is asymptomatic.

Fig. 1: Colonoscopy images showing balloon spacer inserted in the rectal wall (a). Endoscopic removal procedure in small pieces (b). Small fistula orifice (c).

Discussion/Conclusion

Dose-escalated radiation therapy for localized prostate cancer definitely improved disease control. However, significantly higher rectal toxicity rates resulted [2]. Rectal toxicity is regarded as the dose-limiting toxicity [2], and rectal spacers are used to reduce radiation-induced toxicity. This case describes a rare complication caused by a balloon spacer. In our case report, an expert radiologist performed the balloon spacer placement maneuvers without detectable immediate complications. We may elaborate that an unprecise positioning of the needle in the retroprostatic space behind the Denovillier fascia during the balloon placement could have been associated to this complication. Faulty needle positioning has been reported in relation to tissue adhesions and the chronic prostatitis/inflammation process associated to adenocarcinoma [8].

Schörghofer et al. [7] has recentlypublished the largest cohort focusing on spacers acute and subacute complications. Magnetic resonance datasets were analyzed looking for spacer deviations or post procedure hematoma. Still, balloon malrotation and hematoma formation after placement were not identified as complication predictors. Additionally, this study focused on rectal-related complications regarding balloon versus gel spacers. The overall rectal-related lesions’ rate was very low, both at the implantation day and during follow-up, reinforcing the devices’ safety profile. However, 5 cases of rectal perforation were recorded in patients who had a balloon spacer and there were no cases for gel systems. It matters to say that in this study the number of balloon devices significantly outweighed the gel devices. Also, as with our report, the perforations spontaneously healed after removal of the spacer and no surgical intervention was needed. Still, in 1 case, RT had to be interrupted. One can believe that this may have clinical implications and impact the patient’s psychological well-being. Schörghofer et al. [9]stated that the balloons’ rigid structure and size may make them more prone to cause rectal lesions. However, perforation has been reported for gel spacers as well in other cohorts. Still on this subject, similar rates of successful implantation are described for different spacers, but balloons are considered easier to handle [10]. From another perspective, Vanneste et al. [11] compared the cost-effectiveness of treating prostate cancer patients with IMRT and a spacer, versus IMRT only. The spacer was found to be cost-effective due to less severe toxicity, and a reduction in costs associated with side effects.

This spacer system was issued in 2010, and it is considered globally efficacious and safe. Some reports elaborate that this balloon spacer may even be more efficacious than gel spacers for rectal sparing radiation [12]. In our report, this complication was successfully addressed endoscopically, and had no impact on the patient’s treatment plan. As mentioned by Schörghofer et al. [8], we believe that a decrease in major rectal toxicities with spacers in many patients, might be balanced by a slight increase in complication rates induced by the spacer, in a few patients. Nevertheless, spacer indications must not be generalized. We report the case of a patient diagnosed with stage IIIC prostate adenocarcinoma, proposed for IMRT. There is no expectable advantage for spacers during standard regimens. In higher-dose regimens, rectum spacer benefits become more likely to outweigh their risks [8]. Studies on virtual spacers were already performed, and this method may allow to estimate the dose-sparing benefit prior to its placement, and therefore tailor the decision of a spacer implantation [13].

Summing up, the undeniable benefits of balloon spacers in terms of dose sparing need to be weighed against the rare but still existing risks of rectal lesions and perforation. Endoscopists should be aware of this rare scenario, and this complication should be addressed with the patient before placement of such devices.