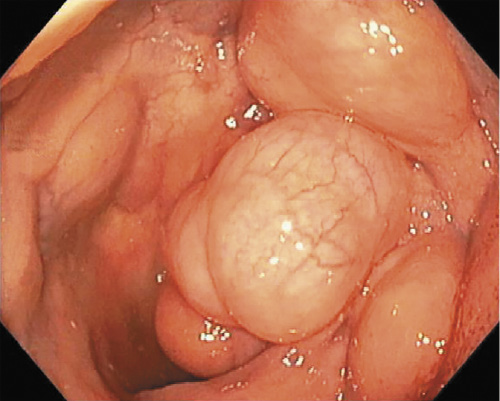

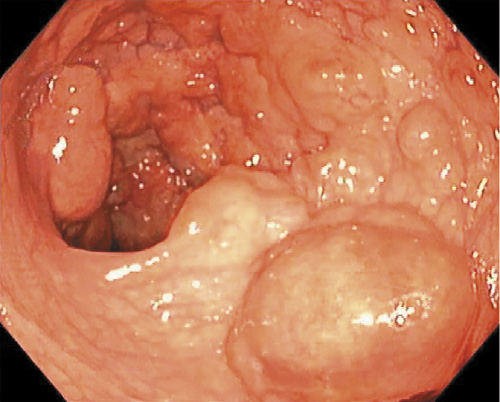

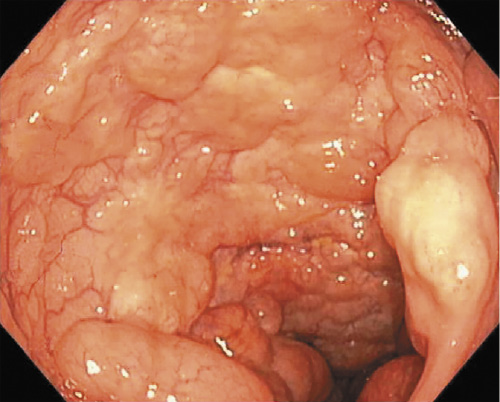

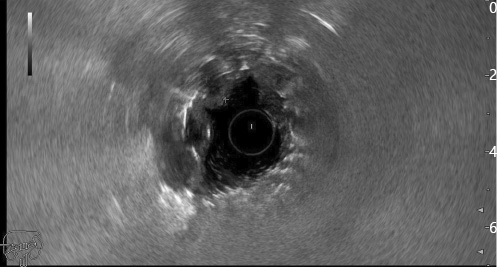

A 67-year-old man with no past medical history presented to the emergency department with a 2-day history of bloody stool. Physical examination revealed no abnormality. Routine biochemical tests and inflammation indices were within normal values. A total colonoscopy was performed and showed multiple, variably sized, and round elevated lesions, with a smooth surface, scattered circumferentially in the distal sigmoid (shown in Fig. 1, 2, 3). An abdominal computed tomography was performed, but no abnormalities were noted. To clarify the diagnosis, an endoscopic ultrasonography was performed. This revealed cystic lesions filled with gas under the mucosal layer (shown in Fig. 4). When the injection needle punctured and aspirated the lesions, they collapsed without releasing any fluid, confirming the diagnosis of pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis (PCI).

Fig. 4: Endoscopic ultrasonography image showing cystic lesions filled with gas below the mucosal layer.

Our patient was referred for a conservative approach with clinical surveillance, and he received a 10-day course of antibiotics (metronidazole 500 mg per os t.i.d.) for symptomatic control. Six months after the diagnosis the patient was asymptomatic.

PCI is a benign and rare disease, characterized by gas-filled cysts in the intestinal submucosa and subserosa [1, 2], and it can be classified as primary (15%) or secondary (85%) [1]. The clinical manifestations are unspecific, and patients may present with abdominal pain, diarrhea, abdominal distension, and, rarely, with bloody stool [1], which was the primary complaint in our case.

The pathophysiological mechanism is still unknown. Three major theories are proposed: (1) the mechanical theory, which assumes there is mechanical damage to the intestinal wall due to an increase in intraluminal pressure, leading to migration of gas to the intestinal wall; (2) the pulmonary theory, which presupposes that chronic lung diseases cause alveolar rupture and release gas from the lungs into the bowel wall via the mediastinum; and (3) the bacterial theory, which posits that gas-forming bacteria penetrate through the mucosa and produce gas within the bowel wall. Other theories, such as that of nutritional deficiency, hypothesize that malnutrition leads to increased bacterial fermentation due to poor digestion of carbohydrates, producing large volumes of gas, ischemia, and submucosal dissection gas. Recently, PCI has also been reported in patients treated with α-glucosidase inhibitors [1].

Although computed tomography is the most sensitive imaging modality to detect PCI [3], several reports show that endoscopic ultrasonography in the colon has clarified the diagnosis of PCI [4, 5]. Additionally, endoscopic ultrasonography has the advantage that there is no radiation exposure involved.

Treatment should be related to the underlying cause of PCI if it results from a secondary cause. Most patients with mild symptoms do not need any treatment. According to clinical severity, treatment including antibiotics, gastrointestinal decompression, parenteral nutrition, fluid and electrolyte supplementation, hyperbaric oxygen therapy, and endoscopic treatment (fine needle aspiration by puncturing the cyst) may be indicated. Surgery is reserved for cases of obstruction, perforation, or precancerous conditions [1].