Introduction

In the last decades, endoscopy has established its position as an essential procedure for the diagnosis, management, and follow-up of multiple benign, premalignant, and malignant diseases. This has led to an increase in the demand for both esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) and colonoscopy [1, 2]. In Portugal, as in many European and North American countries, an open-access system allows referral for endoscopic procedures without the need for prior consultation [3]. Endoscopies are performed either in the public or private setting; in the latter, referral can be made through public or private healthcare subsystems. The goal of this strategy is to avoid unnecessary consultations and minimize waiting lists, but it is not without costs and harm [4]. In fact, concerns regarding inappropriate referrals and the overuse of endoscopy have been raised [5-13]. A 2010 meta-analysis regarding EGDs reported 22% inappropriate referrals [14]. Later studies by Crouwel et al. [15], Abdulrahman et al. [16], and Mangualde et al. [17] reported similar outcomes. Regarding colonoscopy, Gimeno-García and Quintero [18] reported only 75.4% of colonoscopy referrals as appropriate. The appropriateness of the indications can be established through various guidelines; the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) has issued guidelines on appropriate use of gastrointestinal endoscopy [19] and the European Panel on the Appropriateness of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy II (EPAGE II) on the appropriate use of colonoscopy [20]. Of note, most studies report tertiary single-center results.

The aim of this multicenter study was to prospectively evaluate the appropriateness of EGD and colonoscopy referral in private and public settings. Secondary end points were the suitability of referral according to the medical specialty and the diagnostic yield of the procedures.

Materials and Methods

This was a cross-sectional study of patients undergoing elective EGD or colonoscopy at 1 tertiary-referral public hospital, 1 secondary-referral public hospital, and 5 private endoscopy units. Patients aged ≥18 years and scheduled for an EGD or colonoscopy without therapeutic intent were consecutively included. Patients unable to consent or submitted to urgent procedures were excluded. Endoscopic examinations were performed by trained gastroenterologists. Prior to the examination, data such as demographic characteristics, information on previous endoscopies, medical therapy, and alarming features (unexplained weight loss, suspected gastrointestinal bleeding, dysphagia, persistent vomiting, detection of an abdominal mass) as well as an indication, were collected. Indication was determined according to the information available on the referral form, or, when this was unavailable, by the endoscopist after an interview with the patient. Before performing the examination, endoscopists were asked to answer whether they thought the referral was appropriate. After the examination, endoscopic findings were recorded. Findings were defined as relevant if they had the potential to impact on the patient’s management. Indications were reviewed by the investigators. Appropriateness of EGD was defined by the ASGE 2012 guidelines [11] and appropriateness of colonoscopy was defined by the EPAGE II criteria (appropriate/nonappropriate) [12]. The collected data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) v23, with a significance level set at p < 0.05. The χ2 and Fisher exact tests were used to find significant associations between qualitative variables. Odds ratios (ORs) and related 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used to express the extent of the associations found.

Results

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy

Baseline Characteristics

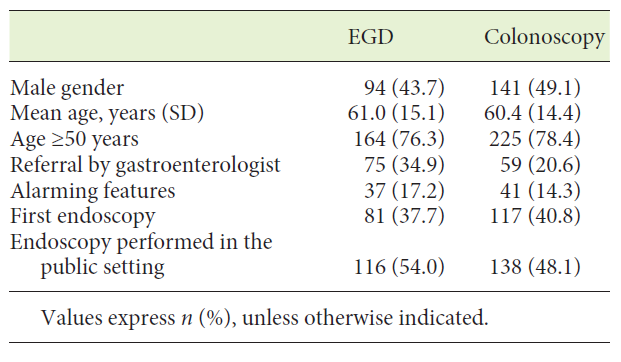

Two hundred and fifteen patients were included in the analysis (Table 1). EGD was performed at public hospitals in 54.0% (n = 116) and at private units in 46.0% (n = 99). Referral for EGD was made by gastroenterologists in 34.9% (n = 75) and by other clinicians in 65.1% (n = 140) patients. The mean age was 61.0 (± 15.1) years and 43.7% were male. Alarming features were present in 17.2% patients. At the time of the examination, 13% (n = 28) of the patients were on nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, 16.3% (n = 35) were smokers, and 40.9% (n = 88) were on proton-pump inhibitors. In 37.7% (n = 81) of the patients, it was the first EGD to be performed.

Indications and Findings

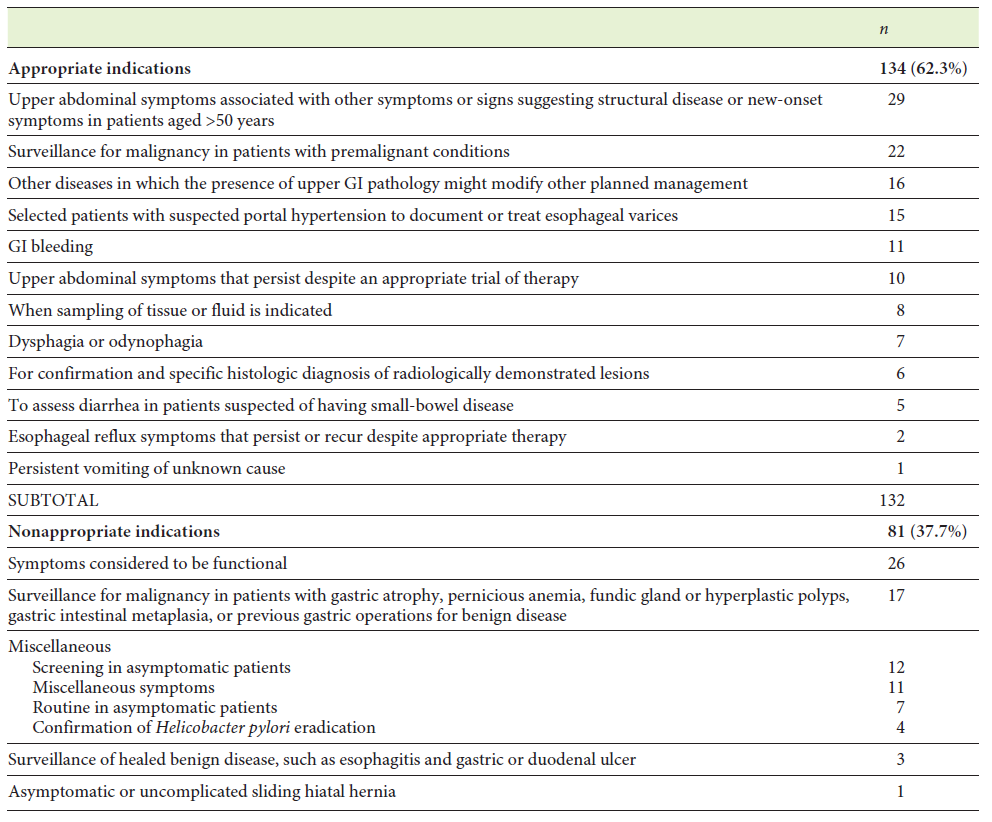

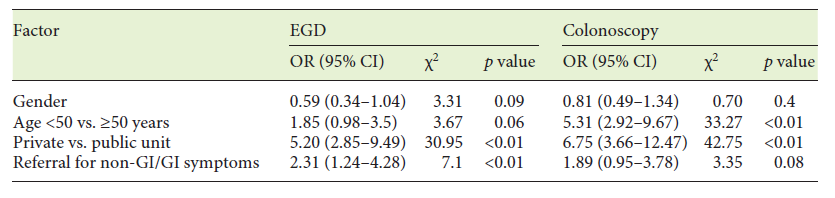

The indications for EGD are summarized in Table 2. Gastroenterologists performing the EGD deemed the indication to be correct in 81.4% (n = 175) of cases. However, review of indications by investigators confirmed that this was according to ASGE criteria in 62.3% (n = 134). The rate of appropriate referral was 42.4% (n = 91) at private units and 79.3% (n = 124) at public hospitals (OR 5.20; 95% CI 2.85-9.49; p < 0.01). A statistically significant difference was also found in the rate of appropriate referral for gastroenterologists (74.7%) versus other clinicians (56.1%) (OR 2.31, 95% CI 1.24-4.28; p < 0.01). Appropriateness of referral was 65.9% for patients aged ≥50 years and 51.0% for patients aged <50 years (p = 0.06; Table 3).

The main appropriate indications were upper abdominal symptoms associated with symptoms or signs suggesting organic disease or new-onset symptoms in patients >50 years (22.0% of the appropriate indications, n = 29), surveillance in premalignant conditions (16.7%, n = 22), and diseases in which the presence of upper gastrointestinal (GI) pathology might modify other planned management (12.1%, n = 16).

Indications not fitting the ASGE appropriateness criteria were classified as inadequate. The main nonappropriate criteria as clearly set by the ASGE were symptoms considered to be functional (32.1% of the nonappropriate indications, n = 26). The remaining exams without appropriate criteria were reviewed and the main indication was screening for malignancy in asymptomatic patients without known premalignant conditions (14.8%, n = 12). Of note, 9.8% (n = 21) EGDs had no written indication on the referral form.

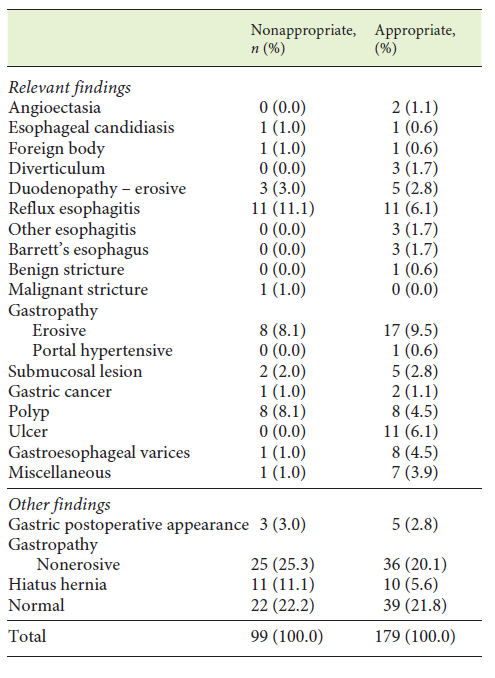

One hundred and twenty-seven relevant endoscopic findings were reported (Table 4). A relevant endoscopic finding was present in 47.9% (n = 103) of the patients. The most common findings were erosive esophagitis and gastritis. Overall, the diagnostic yield for relevant lesions was 34.0% for EGDs with an appropriate indication and 66.0% for EGDs without an appropriate indication. This difference did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.88). Also, no association was found between the presence of alarming features and relevant endoscopic findings (p = 0.3), or between referral by a gastroenterologist and relevant endoscopic findings (p = 1.0).

Colonoscopy

Baseline Characteristics

Two hundred and eighty-seven patients were included in the analysis. Their mean age was 60.4 ± 14.4 years and 49.1% were male. Colonoscopies were performed at public hospitals in 48.1% (n = 138) and at private endoscopy units in 52.9% (n = 149). Referral was made by a gastroenterologist in 20.6% (n = 59) cases. Alarming features were present in 14.3% (n = 41) of the patients. The majority of the study population, i.e., 59.2% (n = 170), had already been submitted to a colonoscopy 4.2 ± 3.7 years previously. Regarding previous colonoscopies, information on bowel preparation and visualization of the entire colon was available in 94.7% (n = 161), with bowel preparation classified as adequate in 71.4% (n = 115) and colonoscopy in 83.9% (n = 135).

Indications and Findings

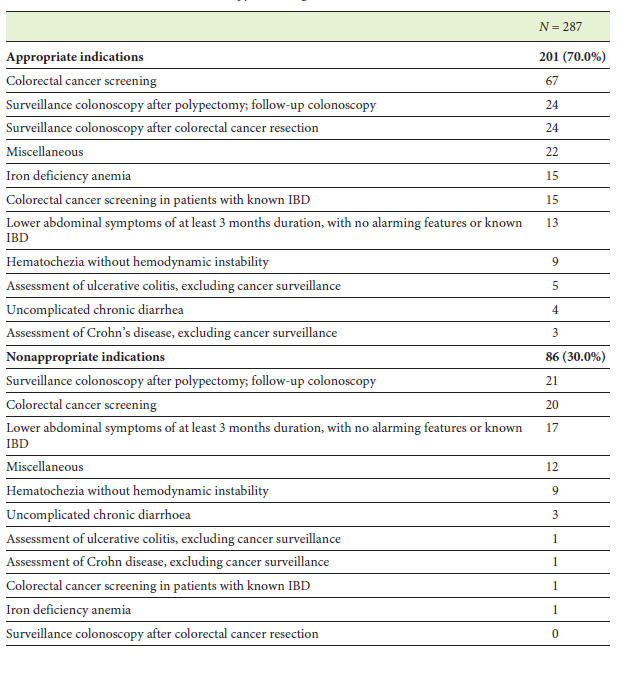

The indications for colonoscopy are summarized in Table 5. Endoscopists considered indications to be appropriate in 87.8% (n = 252) of the cases. However, when EPAGE II criteria were applied, the rate of adequate indication decreased to 70.0% (n = 201; 53.0% for private units and 88.4% for public hospitals [OR 6.75; 95% CI 3.66-12.47; p < 0.01]). Appropriateness of referral was 79.7% by the gastroenterologist and 67.4% by other clinicians (p = 0.08). Appropriateness of referral was 78.2% for patients aged ≥50 years and 40.3% for patients aged <50 years (OR 5.31; 95% CI 2.92-9.67; p < 0.01; Table 3).

The main appropriate indications were screening for colorectal cancer (33.3% of the appropriate indications, n = 67) and surveillance colonoscopy after colorectal cancer resection or polypectomy (23.9%, n = 48). According to the EPAGE II criteria, the most common nonappropriate criterion was surveillance colonoscopy after polypectomy. Of the 30.0% (n = 86) of nonappropriate indications, 36.0% (n = 31) were classified as uncertain.

Endoscopic Findings

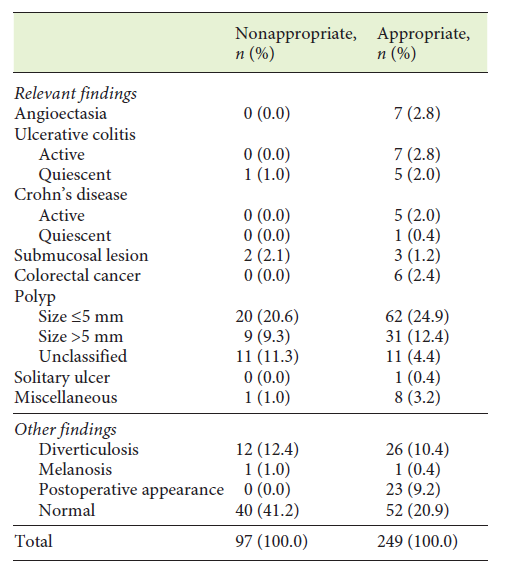

Endoscopic findings are summarized in Table 6. Relevant endoscopic findings were present in 57.1% (n = 164) of the colonoscopies and 32.1% (n = 92) were normal. The most common relevant endoscopic diagnosis was colonic polyps.

Relevant endoscopic diagnosis was associated with the appropriateness of the indication: 63.2% in the appropriate indication group compared to 43.0% (n = 37) in the nonappropriate indication group (p < 0.05). No significant association was found between referral by gastroenterologist and relevant endoscopic findings (p = 0.1). No association was found between the presence of alarming features and relevant endoscopic findings (p = 0.6).

Discussion

Our era has been called the “golden age of endoscopy,” as this resource is now readily available to most patients and clinicians in developed nations [4]. Endoscopy is regarded as a safe, informative, and potentially curative procedure. However, many authors have raised concerns about the overuse and inappropriate use of endoscopy.

Our data on appropriateness of EGD show up to 38.7% procedures without an appropriate indication according to the ASGE and EPAGE criteria, in line with previous reports. These high rates may be explained by a myriad of factors: patient-related (a desire for screening or surveillance programs), clinician-related (the fear of watchful waiting and malpractice litigation, under appreciation of adverse events, and awareness of the endoscopy potential), and system-related (unavailable medical records and monetary compensation). We hypothesize that such factors as well as an endoscopy-driven reasoning, particularly nonadherence to the guidelines, may explain the greater proportion of EGDs considered by gastroenterologists as appropriate. We should also emphasize that an observer bias could not be totally ruled out, and, most importantly, it is arguable whether these international guidelines can be universally applied to all countries. In fact, each country has some specificities, and the accuracy of such guidelines could not be optimized [21].

In our study, the odds of appropriate referral were higher in the public setting than in the private units. Referral for private units was mainly through public healthcare subsystems. These findings could reflect the nonadherence to ASGE guidelines by nongastroenterologists but also the differences in the referral process. In fact, in public hospitals, all requests are subjected to a thorough triage process, but this does not happen in the private setting since the gastroenterologist has access to the referral just before the endoscopic procedure. Of concern, 21 referrals had no written information. This is not acceptable, and the prescription process should automatically be blocked if no information is available.

Observational studies have raised questions about the validity of the ASGE guidelines in identifying relevant endoscopic diagnoses. In our study, the diagnostic yield of these guidelines for relevant findings was indeed disappointing. Also, a significant proportion of relevant findings was found in exams without an appropriate indication. Buri et al. [22] propose simpler, symptom-based criteria. However, in our study, neither the presence of alarming features nor the endoscopist’s view on the appropriateness of the indication were associated with a relevant endoscopic diagnosis. This said, it should be noted that EGDs without relevant findings may actually improve the clinician’s diagnostic yield. Ultimately, and since most of the referrals come from primary care physicians or other specialties, defined criteria as opposed to clinical reasoning may be important in the management of resources [23]. A previous study has already challenged the accuracy of previous ASGE indications for EGD in Portugal. Developing national prescription guidelines would likely result in better outcomes. The importance of nationwide validation of such guidelines cannot be stressed enough, as the strict use of international criteria may ultimately result in an underdiagnosis of GI diseases. Such recommendations would have to be broadly publicized acrossall medical specialties, so as to minimize inappropriate referrals for endoscopic procedures.

For example, a significant proportion of patients was doing the EGD as a form of gastric cancer screening. While it is true that such a screening program is not a reality in our country, these findings probably reflect clinicians’ and patients’ awareness of the high rates of gastric cancer in Portugal and the need to discuss the implementation of such a program [24].

Regarding colonoscopies, 30.0% of the indications were classified as nonappropriate (including inappropriate and uncertain indications). The prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the study population reflects the nature of the hospitals. As with EGD, the odds of appropriate referral were significantly higher in the public setting than in private units and considered to be of clinical importance. An important percentage of the nonappropriate indications (48.8%) concerned surveillance and screening programs. It should also be stressed that key performance measures for colonoscopy were suboptimal, as the global rate of both adequate bowel preparation and cecal intubation was <90%. Importantly, no colorectal cancer was identified in the nonappropriate colonoscopy indication group. Early repetition of colonoscopy is well-documented in the literature. While it is true that evidence of optimal screening time is limited, gastroenterologist’s opinion on screening intervals, multiplicity of recommendations, and a patient’s wishes may ultimately lead to these findings. As the workload and the pressure on both public and private health systems increases, and since colonoscopy is not without risks, the ongoing discussion on surveillance programs and quality measures in colonoscopy seems to be essential. This is of paramount importance in the period since the COVID-19 pandemic, as there has been a decrease in the response capabilities of endoscopy units, and a correct triage of procedures is a priority to be able to perform procedures deemed as necessary. A multidisciplinary discussion is urgently needed to establish clear referral criteria and correct use of health resources. Strategies like “Choosing Wisely” must be optimized and publicized for clinicians to have correct information about the appropriate indications for endoscopic procedures.

In conclusion, we believe this study is significant as it portrays the current situation in an open-access system supported by both public and private healthcare units. Although a significant number of endoscopic procedures have an appropriate indication, there is room for further improvement. The pressure with which the system is faced nowadays has made it imperative to guide our practice by the medical standard of care. Endoscopy has proven to be a fundamental aid in the diagnosis of digestive diseases, and it will reach its full potential when referral is appropriate.