Introduction

Mutations in the CDH1 gene cause deregulation of the E-cadherin tumor-suppressing mechanism, thereby conferring a cumulative risk of developing signet-ring cell (diffuse) gastric cancer in carriers, of up to 70% by the age of 80 years and a mean age at diagnosis of 38 years [1 ]. Considering that patients often show multiple foci at an early age and the high mortality related to diffuse gastric cancer, prophylactic total gastrectomy (PTG) is recommended at a young age (20-30 years), regardless of endoscopic findings [ 2, 3 ].

In CDH1 mutation carriers, an index high-quality endoscopy according to the Cambridge protocol [ 4 ], with additional targeted biopsies of any visible lesion, should be performed to search for macroscopic and microscopic tumors and exclude heterotopic gastric mucosa or others lesions that may alter the extent of the resection or therapeutic approach [ 5 ].

In those not fit for surgery (due to comorbidities) or who choose to postpone PTG, an annual high-quality surveillance endoscopy is advised to help the decision-making process if microscopic foci of signet-ring cells are detected [ 6 ].

Marginal zone B-cell lymphoma (MZL) of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT lymphoma) is the most common type of marginal zone lymphoma, representing 5-8% of all B-cell lymphomas. The gastrointestinal (GI) tract is frequently affected, particularly the stomach [ 7 ].

We report the case of a 23-year-old male with a known mutation of the CDH1 gene, under a surveillance program for gastric cancer, who received a diagnosis of MALT lymphoma. We also report the subsequent management.

Case Report

This patient was referred to our institute due to a family history of hereditary diffuse gastric cancer (HDGC). The presence of the mutated gene was confirmed, and he was advised to have a PTG.

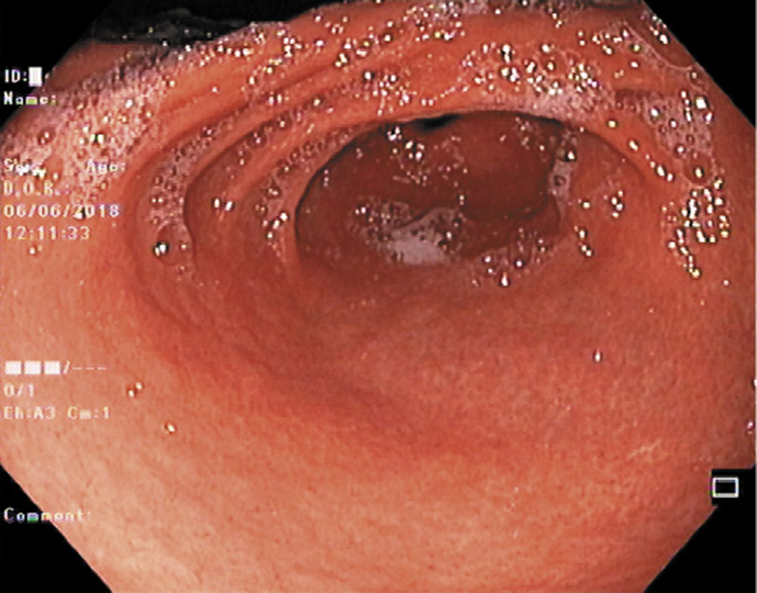

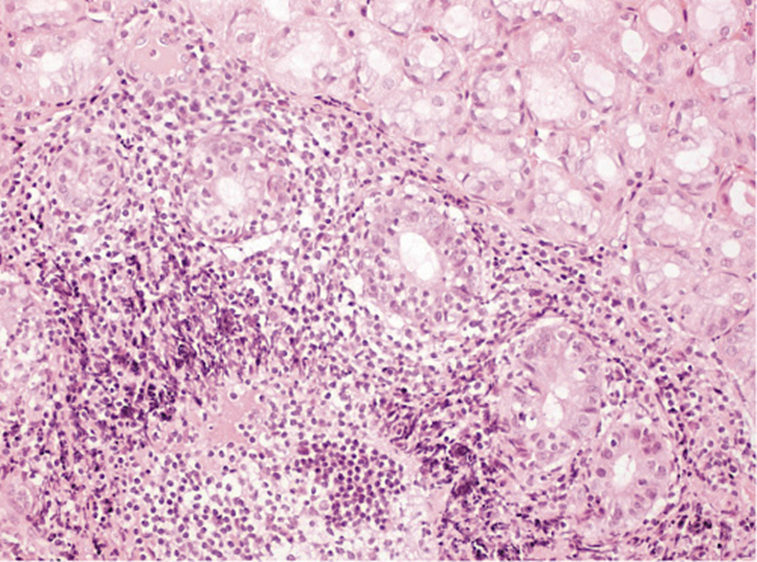

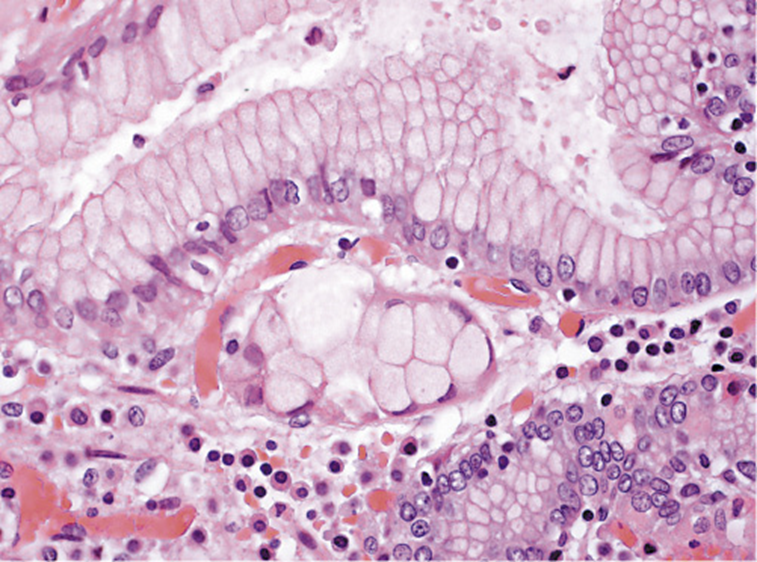

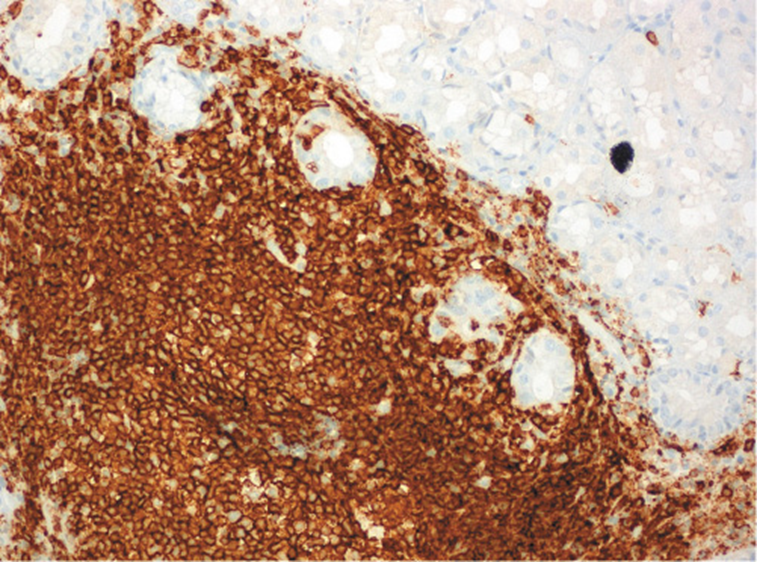

He was submitted to a surveillance endoscopy with biopsies according to the Cambridge protocol that showed a chronic gastritis with Helicobacter pylori. At this point, the patient consented to the surgery, so it was decided not to eradicate the H. pylori. By patient’s decision, the surgery was postponed and an upper GI endoscopy was scheduled. No visible lesions were detected (Fig. 1), but histology of the corpus-antrum transition revealed signs of inflammatory infiltrate, and lymphoid follicles with alterations suggestive of extranodal MALT lymphoma, with a score of 4 according to the classification of Wotherspoon et al. [ 8 ] (Fig. 2). The immunohistochemistry study revealed CD20+, CD3-, Bcl2+, focal CD21+, CD10-, and signs suggesting the production of κ light chains (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3: Immunohistochemistry study revealing CD20+ in corpus-antrum transition: extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma (MALT).

The patient was informed of this result and prescribed the bismuth quadruple therapy eradication treatment. He also underwent a thoraco-abdomino-pelvic computed tomography scan that showed no further involvement (stage I). Given these findings, the patient consented to undergo PTG. H. pylori fecal antigen was negative, confirming eradication.

The surgery was performed without complications and there was no evidence of intraabdominal metastases or involvement of the 26 isolated ganglia. The histologic examination of the specimen identified 2 foci of signet-ring cell carcinoma (SRCC)in situ in the body region, without invasion of the lamina propria (Fig. 4). There were no signs of MALT lymphoma. He was proposed to undergo surveillance at a multidisciplinary meeting.

Discussion

Due to the poor prognosis associated with diffuse gastric cancer (DGC) and the high probability of CDH1 mutations carriers to develop it, the best risk reduction strategy is PTG.

Only 10% of the patients who develop symptomatic invasive DGC have a potentially curable disease and, even in this group, the 5-year survival rate does not exceed 30% [ 6 ].

However, surgery has significant implications for quality of life and nutritional status, so the timing should be individualized, with some patients deciding to postpone the procedure [ 9 ].

In this setting, gastroscopy performed by experienced endoscopists has an important role in this risk group’s surveillance [ 10 ]. Annual endoscopy following the Cambridge protocol (5 random biopsies from 6 different anatomic sites) is advised for to optimize diagnosis, due to the small size of the foci of signet-ring cells that can only be recognized by microscopy. White-light exam is recommended, since other endoscopic modalities have not been proven to confer any additional benefit. Gastrectomy may be necessary when macroscopic or microscopic disease is found [ 11 ]. Despite all efforts, gastroscopy with random biopsies has low sensitivity to detect SRCC [ 12 ].

During the previous year, our patient had produced negative endoscopic and histological findings. Although there is no proven association between H. pylori infection and HDGC, testing via gastric biopsy is recommended, because they frequently coexist and may play a role in inducing DGC [ 13 ]. Additionally, H. pylori is a class I carcinogen, and its treatment and confirmation of eradication are advised for those who test positive [ 6, 14 ]. In this specific case, it was decided not to eradicate the H. pylori because PTG was already planned in the short term. Despite initially accepting surgery, subsequent postponement resulted in endoscopic surveillance and active H. pylori infection through this period.

H. pylori is associated with gastric MALT lymphoma in >90% of the cases and its eradication should be the only initial therapy for a localized H. pylori-positive lymphoma as well as being considered in H. pylori-negative patients with a false-negative test or infection by other Helicobacter spp. It results in lymphoma regression and long-term clinical control in the majority of patients [ 7, 15 ].

MALT lymphomas typically have an indolent course and tend to be self-limited if the H. pylori infection stimulus is no longer present [ 7 ]. In our patient, a PTG was already planned and the timing of surgery was dictated by the diagnosis of gastric MALT lymphoma. The surgical specimen revealed only foci of SRCC; no lymphoma was identified, which showed the response to the H. pylori eradication treatment.

Reports of advanced DGC in patients with multiple negative surveillance exams are frequent because the endoscopic detection of SRCC foci is poor [ 11, 16 ]. After surgery, multiple foci of intramucosal (T1a) SRCC are found in 45-60% of patients with negative endoscopic evaluations [ 6, 17, 18 ].

Our literature review found some clinical reports of coexisting diagnoses of gastric MALT lymphoma and sporadic DGC, but none reporting gastric MALT lymphoma in CDH1 mutation patients [ 19-21 ]. This can be explained by the low prevalence/underdiagnosis of HDGC and the prophylactic/curative gastrectomy early in life which reduces the chance of this kind of lymphoma developing.

To our knowledge, this is the first report of a patient with a known mutation of the CDH1gene diagnosed with a gastric MALT lymphoma while undergoing endoscopic surveillance. Despite having a higher risk of developing neoplasia (and this is the primary screening focus), these patients should also be screened for otherwise-common pathologies, the presence of which may determine different treatment strategies.