Introduction

The first presentation of ulcerative colitis may be an acute flare in about 15% of patients (1). These cases often require hospital admission so that a workup can be performed and adequate treatment can be provided.

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) belongs to the Herpesviridae family, and primary infections in immunocompetent individuals are usually unremarkable (2). However, virus reactivation in immunosuppressed patients poses a serious threat, capable of multiple organ damage (2, 3). Currently, CMV disease should be sought in active severe ulcerative colitis, because it is a frequent cause of steroid refractory disease (1). In order to improve the diagnosis of actual CMV disease, rather than infection, detection of CMV DNA by PCR or histopathology combined with immunohistochemistry is preferred over serology (4).

Herpes simplex (HSV) types 1 and 2, on the other hand, have a less clear role in the exacerbation of ulcerative colitis. Herpes simplex colitis constitutes a rarer event in ulcerative colitis patients (4-7) and it is usually associated with immunosuppression (8). Nonetheless, it warrants a swift diagnosis and treatment to prevent poor outcomes (5-7).

We report a case of a first presentation of ulcerative colitis complicated by CMV and herpes simplex type 2 coinfection.

Case Report/Case Presentation

A 63-year-old female patient with no previous medical history besides an anxiety disorder, usually medicated with cloxazolam, presented to her local hospital with a 1-month history of bloody diarrhea (5 bowel movements per day), colicky abdominal pain, urgency, and fever. She denied weight loss, recent use of antibiotics, or recent travel. In the emergency department, the physical examination was unremarkable apart from mucosal pallor. The patient presented a hemoglobin level of 9.6 g/dL, a C-reactive protein level of 14 g/dL, and albumin level of 2.0 g/dL. Stool testing for Clostridium difficile, as well as parasitical and bacterial cultures, were negative. In the left-sided colonoscopy, continuous mucosal erythema and friability were seen from the distal rectum up to the descending colon, with deep ulcers in all segments, the biopsies of which showed an active colitis pattern without identification of pathogenic microorganisms. Immunohistochemistry for CMV was negative.

She was then admitted and started on mesalazine and intravenous steroids, after a failed cycle of ciprofloxacin, with an assumed diagnosis of ulcerative colitis. During the next 2 months the patient was maintained on systemic corticosteroids, without clinical remission, and developed numerous complications such as respiratory infections, anemia requiring blood transfusion, and diabetes due to corticotherapy.

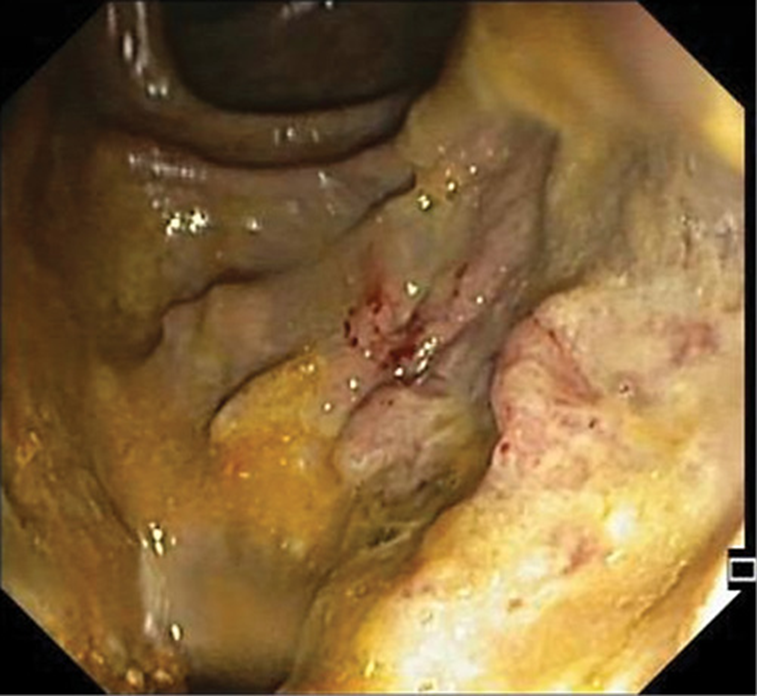

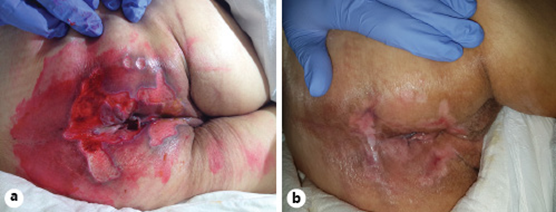

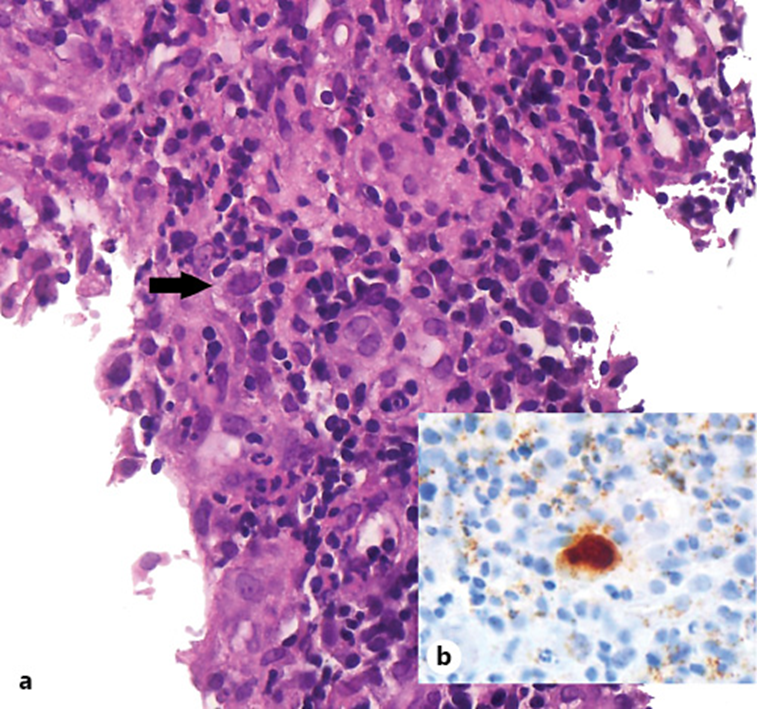

At that point she was diagnosed with severe sepsis due to nosocomial pneumonia and she was transferred to our hospital, where she arrived tachycardic, requiring supplementary oxygen (FiO2 40%), confused, tachypneic, and with muscle wasting. The patient presented ulceration of the perianal region, with multiple, linear, exudating ulcers deriving from the anal verge. The left-sided colonoscopy revealed loss of the vascular pattern, diffuse congestion and erythema and focal areas of superficial ulceration combined with other areas of inflammatory polyps (Fig. 1). Considering the clinical course, the perianal ulceration, and the endoscopic findings, biopsies were made and a tissue analysis by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was positive for CMV DNA and herpes simplex type 2 DNA. Concerning serology, IgG and IgM for CMV were both positive and for HSV type 2 there was positive IgG but negative IgM. The histopathologic examination confirmed the diagnosis of CMV infection (Fig. 2). Both intravenous ganciclovir and aciclovir were started in order to cover CMV and HSV type 2, and steroid tapering was initiated.

Fig. 2: Histological findings of the colon biopsy specimen. a Cells with enlarged nuclei containing basophilic intranuclear inclusions. H&E. ×400. b Immunohistochemical staining for CMV. ×400.

The sepsis responded well to antibiotic treatment and after 2 weeks of treatment the diarrhea had significantly improved, so acyclovir was stopped and ganciclovir was switched to oral valganciclovir. However, the perianal ulcers were not taking a favorable course. The PCR from the skin biopsy was negative for CMV and HSV DNA and the histopathologic analysis was coincident with a nonspecific ulcer. In addition, a rectovaginal fistula 5 cm from the anal verge was found in the follow-up colonoscopy. In consideration of the above, after discussion with the surgical department, a protective ileostomy was performed on the 30th day of admission.

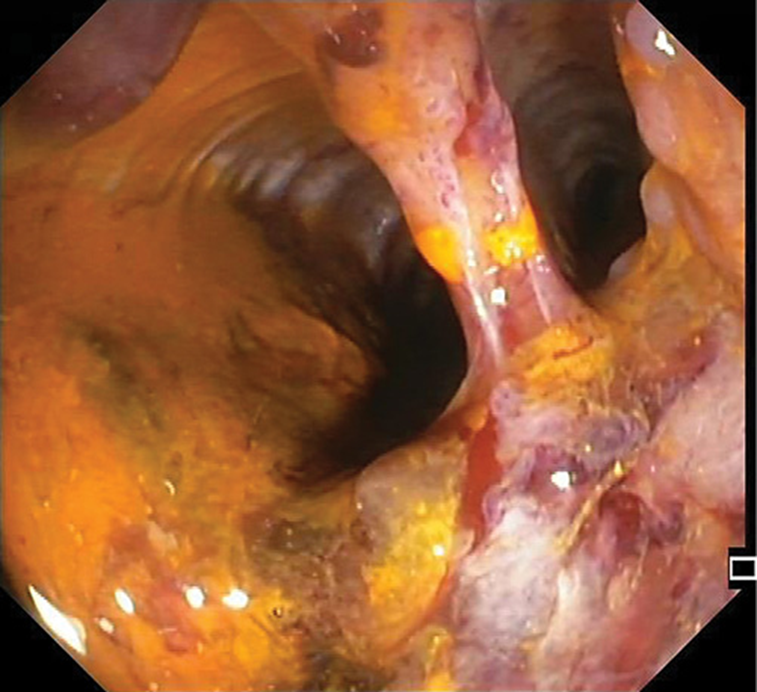

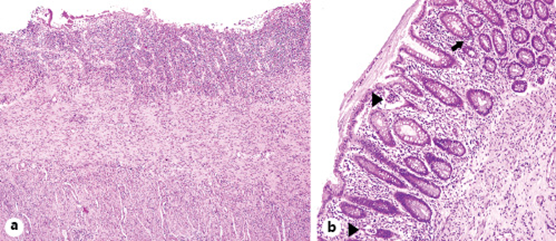

The patient then underwent a physical rehabilitation program while waiting to be transferred to a rehabilitation healthcare unit. With respect to the perianal ulceration, it progressively improved after the ileostomy (Fig. 3). In order to access endoscopic activity and decide on the course of treatment before discharge, a colonoscopy was performed, revealing a contained colonic perforation 30 cm from the anal verge, giving access to the retroperitoneum (Fig. 4). An abdominal CT confirmed the perforation and the patient was submitted to total proctocolectomy and terminal ileostomy on the 53th day of admission, which was considered a more definitive and safer treatment. Histopathologic examination of the surgical specimen revealed, from the distal rectum to 5 cm distal to the ileocecal valve, extensive areas of mucosal ulceration covered by fibrinoleucocyte exudate and the formation of granulation tissue up to the muscularis propria. In the colon, multiple filiform pseudopolyps were seen. In the distal 5 cm of the rectum, polymorphic inflammatory infiltrate in the lamina propria and cryptic abscesses were both observed (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5: Histological findings in the surgical specimen. a Area of ulceration. H&E. ×40. b Mucosa with mild glandular architectural disarray, cryptitis (arrow), and crypt abscesses (arrowheads). H&E. ×100.

Once the postsurgical period had been overcome, the rehabilitation program was resumed and the patient was discharged to another healthcare facility to continue her recovery. Two months later, she returned for observation as an outpatient, with remarkable improvement; she was able to walk with some help, and she was asymptomatic and presented complete healing of the perianal ulcers.

Discussion/Conclusion

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first case of CMV and HSV type 2 coinfection in an ulcerative colitis patient.

Despite the fact that some features, such as the recto-vaginal fistula and the perianal ulcers, suggested Crohn’s disease, the endoscopic and histopathologic characteristics pointed toward ulcerative colitis.

A conclusive etiologic diagnosis for the perianal ulcers could not be made. On the one hand, the possibility of cutaneous HSV or CMV infection must be considered. Genital and perianal ulcers are the typical lesions of HSV type 2 (9) and the most frequent manifestation of cutaneous CMV (10). Conversely, no viral DNA was found by PCR of the skin biopsy tissue. On the other hand, cutaneous involvement by Crohn’s disease is part of the differential diagnosis. Perianal ulceration is the most common pattern of skin ulceration in Crohn’s disease (11, 12). Yet, as previously mentioned, ulcerative colitis seemed a stronger possibility and this kind of perianal disease is rare in that condition. In addition, the histopathology of the skin lesion did not reveal any features suggestive of Crohn’s disease. Finally, the diagnosis of pressure ulcers should not be overlooked in a debilitated, bedridden patient who was dependent for hygiene care. In consideration of the above, this last hypothesis presents as the most likely, since the ulceration improved after stool transit diversion.

A retrospective study of acute severe UC found that recent therapy with high-dose steroids and colonoscopy with deep ulcers/higher Mayo scores were associated with CMV disease (13), both of which were present in this patient. The same applies to other predictive factors previously identified, i.e., increasing age, duration of disease of <5 years (14), and immunosuppressive therapy (14-16). CMV colitis is associated with worse outcomes in severe ulcerative colitis (13, 17, 18). In fact, there are some reports of colonic perforation in CMV colitis (19-22). However, in this case the patient seemed to be improving and had already undergone several weeks of antiviral treatment, which hazes the role of CMV in this outcome.

Regarding the HSV infection, one could argue that it was only found by PCR, which has a high sensitivity, and it could be only an accidental finding. However, PCR for viral DNA from tissue biopsies is a valid method of diagnosis (4) and, considering the severity of this case, specific treatment was mandatory. Although it is an exceptional diagnosis compared to CMV disease in acute severe ulcerative colitis, it should be borne in mind as otherwise a treatable cause of exacerbation will be missed.

Ganciclovir and aciclovir are the first-line treatment for CMV and HSV disease, respectively (4, 23). Neither is considered adequate for the treatment of both disorders. Consequently, both were rapidly started once the diagnosis had been made. Concerning the duration of treatment, a 2- to 3-week course is usually recommended, with the possibility of switching from ganciclovir to valganciclovir for oral treatment, depending on the clinical course (4, 24). Similarly, acyclovir is prescribed between 2 and 3 weeks in HSV colitis (5, 7).

In conclusion, this report highlights the importance of a high degree of suspicion for opportunistic infections in steroid/immunomodulator refractory ulcerative colitis, even in the first flare.