Introduction

Non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHL) are a common hematologic malignancy, but only 5-15% of the cases can be classified as marginal-zone lymphomas (MZL). Over the last 2 decades, the overall incidence of MZL has increased, possibly related to improvements in pathological diagnosis [1]. Up to two-thirds of these present as an extranodal neoplasm, such as mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma, with the stomach being the most common site of involvement, due to chronic inflammation associated with Helicobacter pylori infection which is present in up to 90% of the patients [2]. Ocular adnexa, the lungs, and the salivary glands follow. Disease of the colon occurs in only 2.5% of cases [3]. In contrast to its gastric counterpart, the pathophysiology of colonic MALT lymphoma is not well understood, resulting in limited therapeutic options [4].

We present a rare case of MALT lymphoma with colon involvement exhibiting unusual endoscopic findings.

Case Report

A 61-year-old woman was referred to our unit after a positive fecal occult blood test (FOBT) for colorectal cancer screening. Her medical history was significant for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and total gastrectomy for unknown reasons >20 years prior to admission. Premedication included the inhaled bronchodilators salbutamol and formoterol. There was no family history of digestive tract neoplasms. Prior to being evaluated at our center, the patient had undergone a colonoscopy, with the report describing an ulcerated, irregular lesion on the ileocecal valve with an inconclusive histological sample. Upper endoscopy showed a total gastrectomy with no other relevant findings.

On admission, the patient denied any digestive symptoms such as abdominal pain, overt gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, intestinal transit changes, or systemic symptoms like fever, weight loss, night sweats, and anorexia. Physical examination showed a soft, nondistended abdomen, with no tenderness and normal bowel sounds. No palpable lymph nodes were noted. Blood tests revealed normal hemoglobin, leukocyte count, iron parameters, haptoglobin, β2-microglobulin, C-reactive protein, and lactate dehydrogenase.

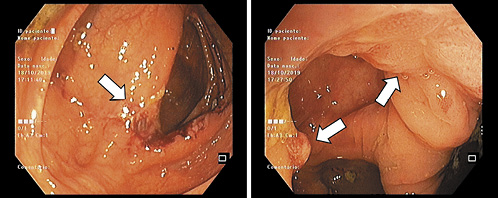

A decision was made to repeat colonoscopy with lesion sampling at our center. At this procedure, an area of irregular mucosa with approximately 15 mm adjacent to the ileocecal valve was observed (Fig. 1a). This lesion had a congestive appearance, with superficially ulcerated areas and a pseudo-polypoid component. On the hepatic flexure, additional areas of mucosa ranging from 5 to 10 mm with similar characteristics were seen (Fig. 1b). The remaining colon segments had no endoscopic abnormalities. The first endoscopic impression was of an ischemic or drug-induced colopathy, but the patient had neither a history of cardiovascular risk factors nor a regular consumption of drugs associated with colorectal mucosal disruption.

Fig. 1 a Endoscopic image of ileocecal valve lesion (white arrow). b Endoscopic image of hepatic flexure lesions (white arrows).

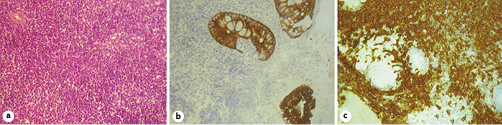

Separate biopsies were taken from both locations and presented similar results. Adding to the presence of fibrin and leukocyte exudates compatible with ulceration, the mucosa was also expanded by populations of atypical lymphoid cells (Fig. 2). Immunohistochemical stain of the biopsy specimens concluded that the neoplastic cells were positive for CD20 and CD43 and negative for CD3, CD5, CD10, cyclin D1, and CD23. These morphological and immunohistochemical characteristics are compatible with MALT extranodal marginal zone B cell lymphoma.

Fig. 2 Histological images. a Infiltration of the colonic mucosa by atypical lymphoid cells. HE. ×40. b Immunohistochemical staining for cytokeratin AE1/AE3. ×40. c Immunohistochemical staining for CD20. ×40.

Thoracic, abdominal, and pelvic computed tomography (CT) without contrast (due to a known history of allergy) was performed. The images displayed many nodular lesions in both lungs, the largest located in the superior left lobe with a size of 31 × 34 mm (Fig. 3); biopsy revealed it as compatible with additional areas of MALT lymphoma involvement. There were no other lesions observed in the abdominal or pelvic plans including nodal involvement areas. Bone marrow biopsy was performed and showed no signs of disease infiltration. These areas of involvement classified this patient’s lymphoma as a stage IV disease according to the Lugano staging system [5].

Fig. 3 Thoracic CT scan showing the larger pulmonary lesion in the superior left lobe (white arrows).

Due to the disseminated state of the disease, systemic treatment with bendamustine and rituximab was initiated. Concerning prognosis, this patient presented with a MALT-IPI index of 1, considered to correspond to an intermediate risk [6].

Up to the time this paper was submitted (5 months after the diagnostic colonoscopy), the patient is still asymptomatic and under chemotherapy treatment.

Discussion

MALT lymphomas were first described in the early 1980s as low-grade B cell neoplasms with extranodal presentation [7] and have now grown to become the third-most common B cell NHL, representing up to 9% of cases [8]. They have a predilection for the GI tract, with this pathological entity being most known for its gastric involvement. The pathophysiology behind this association is firmly understood, as infection by H. pylori plays a pivotal role in the process [2]. The stomach is the primary location in 60-75% of patients [9], but a MALT lymphoma may also be located in the esophagus, small bowel, colon, or rectum [10, 11].

Two different pathways are proposed for overall MALT lymphoma development; one originates from normally present lymphoid tissue like Peyer patches in the gut, and the other results from acquired lymphoid tissue appearing in response to inflammation after infections, autoimmune disorders, inflammatory bowel disease, and immunosuppression, none of which was present in this patient [12].

Colorectal disease is the least common GI location, resulting in a nonelucidated pathogenesis, since the classical risk factors for gastric MALT lymphoma, like H. pylori infection, do not play a similarly preponderant role [11]. However, in a recent review of the literature by Won et al. [12], about 20% of patients with MALT lymphoma affecting the colon and rectum had a positive test for H. pylori infection, indicating that this pathogen may partially influence the development of this disease, even in the large intestine. This does not seem to have been the case in our patient, as she had been submitted to total gastrectomy 2 decades before presentation. Other bacterial agents, such as Borrelia afzelii, Campylobacter jejuni, Chlamydia psittaci, and Mycobacterium spp., have been linked to the onset of MALT lymphoma, but none of them has a clearly reported association with colorectal disease [13].

Colon MALT lymphoma mostly affects individuals in their fifth to seventh decades, with a slight predominance in the female gender, in line with our case report [14]. This neoplasm is often asymptomatic and discovered incidentally on routine colonoscopy. Reported symptoms, if present, are abdominal pain, weight loss, diarrhea, constipation, hematochezia, or, in rare cases, a palpable abdominal mass [15]. Analytically, it can also be diagnosed after the presence of mild anemia or positive FOBT, as was the case of this patient.

On endoscopic examination, MALT lymphoma with colonic involvement has a diverse range of manifestations. The most common is the existence of a single polypoid lesion, but it can also appear as multiple polypoid lesions, or, even more rarely, as nodular or ulcerated lesions [16]. Our case faces the odds as it consisted of a doubly uncommon manifestation of the disease, presenting with multiple lesions and as an ulcer-like manifestation.

Location within the colon varies according to the series. In previous reports, most of the colorectal MALT lymphomas developed in the cecum or ascending colon, with >70% being proximal to the hepatic flexure [13], as was observed in our case. However, more recent series have indicated the rectum as the most commonly affected segment and accounting for 39% of cases [12].

According to the 2016 World Health Organisation Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues, the histology of MALT lymphoma comprises infiltration of the mucosa by monocytoid B cells, centrocyte-like cells, and small lymphocytes [8]. It is possible that epithelial lesions of >3 monocytoid lymphocytes even cause the distortion of mucosal glands. The immunohistochemical panel, according to the European Society of Medical Oncology guidelines, consists of mandatory positive staining for CD20 and obligatory negative staining for CD5, CD10, and cyclin D1. Negativity for IgD and the Myd88 mutation is also suggested. CD23 may be negative or positive [17]. Our case matched all these requirements.

MALT lymphoma involving the colon may present with simultaneous lesions occurring at other sites in the GI tract, such as the stomach or the duodenum, which may be observed in up to 12% of the cases [12]. Synchronous lesions must be sought by performance of upper endoscopy, bone marrow biopsy, and thoracic and abdominal CT. Our patient underwent all of these procedures. Only the CT scan revealed disease involvement, showing nodular lesions on both lungs and a subsequent biopsy compatible with MALT lymphoma.

The majority of MALT lymphomas are of a low grade when first diagnosed. Extranodal MZL usually remain localized for a long period of time, but involvement of the lymph nodes or additional mucosal sites may be present at diagnosis, as was seen in this case. This disseminated form of the disease is particularly common in nongastric MALT lymphomas, being described in 25-50% of cases[18]. In previous reports, colorectal MALT lymphomas presented exclusively in the GI tract in around 70% of the patients [15], with disseminated extranodal involvement or concomitant nodal involvement seen in about 30% of the cases. MZL with lymph node or bone marrow involvement carry a worse prognosis, but the same is not verified in patients with involvement of multiple mucosal sites, as in our case [19].

Overall, colorectal MALT lymphomas carry a good prognosis compared to other lymphomas involving the colon and rectum, such as diffuse large B cell and T cell lymphomas, regardless of the initial stage of the disease [15]. Extranodal MZL-specific prognostic indices have been proposed, such as the MALT-IPI index [6], an accurate tool for both gastric and nongastric MALT lymphomas which classifies the patients as low-, intermediate- or high-risk. The 5-year event-free survival rate is significantly influenced by this index; however, it is still not a factor that influences the treatment decision. Our patient presented with a MALT-IPI index of 1 (age <70 years, normal lactate dehydrogenase, and an Ann Arbor classification IV), which predicts a 5-year event-free survival of 56% and an overall survival of 93%.

The classical gastric MALT lymphoma has better-known therapeutic options, as the mainstay of treatment for localized disease consists of antibiotic treatment for H. pylori infection, with complete remission being achieved in 70-80% of the cases [20]. As for colon disease, the same cannot be applied as there is no current standardized treatment. Anti-infective therapy cannot be currently recommended for this setting. Radiotherapy is the preferred option for treating localized disease, but one must be aware of its possible long-term complications. Surgery has not been shown to achieve superior results when compared to less invasive approaches to extranodal MZL [21]. For patients who require systemic treatment (disseminated disease, contraindications, a failure to respond to local therapy, and histological transformation), chemotherapy, immunotherapy, or a combination of both, are all effective. Generally accepted pharmacological choices include either rituximab alone or in combination with other agents such as chlorambucil, bendamustine, or lenalidomide [17]. Since the pathophysiology of colon MALT lymphoma is still a matter of debate and therapeutic options are not as well-known as those for gastric disease, enrolling patients in clinical trials should be encouraged.