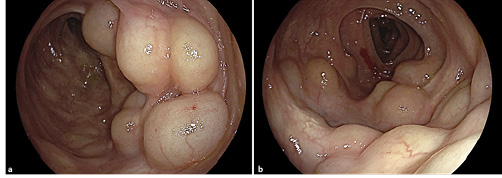

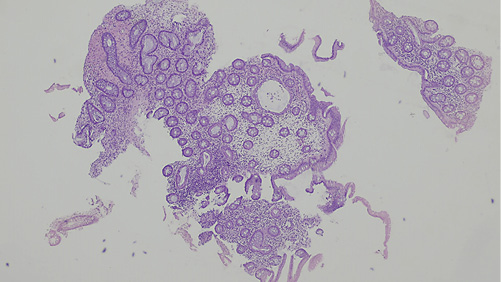

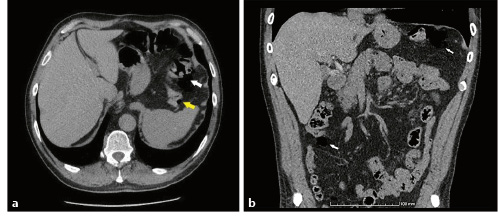

A 51-year-old man, former smoker (20 pack-years), with hemorrhoidal disease, irritable bowel syndrome, pulmonary emphysema and a mechanical prosthetic aortic valve under warfarin, presented for post-polypectomy surveillance colonoscopy. He complained of frequent tenesmus, diarrhea (2-3 liquid dejections in the morning), bloating and abdominal discomfort. Several polypoid grape-like submucosal masses were identified in a 10-cm segment of the descendent colon (Fig. 1a, b). Since the lesions were easily indented with gentle pressure and had a bluish hue, pneumatosis cystoids intestinalis (PCI) was suspected. Biopsy of one of these masses caused immediate deflation, confirming the diagnosis. Histopathological evaluation showed normal crypt architecture and a congestive edematous lamina propria with minimal inflammatory infiltrate suggesting reactive changes (Fig. 2). The patient had no history of abdominal trauma and no pharmacological (alpha-glucosidase inhibitors, steroids) or infectious (Clostridioides difficile, tuberculosis, human immunodeficiency infection) causes. Over a long-term follow-up of 12 years, the mild symptoms were managed conservatively with loperamide, spasmolytics and probiotics, which showed an improvement. In this period, two surveillance colonoscopies were performed showing the same unchanged endoscopic findings described above. Recently, due to surveillance of an ascending aortic aneurysm, a contrasted chest computed tomography (CT) identified a small pneumoperitoneum in the left subphrenic region. Abdominal CT extension showed more free peritoneal air in the left hypochondrium and air bubbles adjacent to the lumen of the bowel, some of them being subserosal (Fig. 3a, b).

Fig. 2 Pathological findings with hematoxylin and eosin stain (×40): normal crypt architecture and a congestive edematous lamina propria with minimal inflammatory infiltrate suggesting reactive changes.

Fig. 3 a, b Abdominopelvic CT scan, axial section (a) and coronal section (b). Pneumoperitoneum and air bubbles adjacent to the lumen of the bowel (white arrows), some of them in subserosal location (yellow arrow).

The prevalence of PCI is 0.03% in the general population and its pathogenesis is poorly understood [1]. PCI is characterized by the presence of gas, forming multilocular cysts, in the intestinal wall ranging from an incidental finding to a life-threatening intra-abdominal condition [1, 2]. In 85% of cases, PCI is secondary to several conditions including immunological disturbances, infections, pulmonary disorders and diseases affecting gastrointestinal motility [3, 4]. In these cases, the main symptoms and also treatments are related to the primary disease. In the remaining 15%, PCI is idiopathic [3]. Most patients are asymptomatic or paucisymptomatic and do not need treatment [1, 2]. When symptomatic, PCI can present with diarrhea, hematochezia, abdominal pain and/or distention, constipation, flatulence, loss of appetite and tenesmus [1, 2]. Antibiotics, elemental diet as well as inhalational and hyperbaric oxygen therapy have been used, although the evidence to support their efficacy is limited and the recurrence rate is high. The diagnosis of PCI is based on endoscopy or imageology [1, 2]. Endoscopically, cysts have a pale or bluish appearance and vary in size from a few millimeters to several centimeters, and when biopsied, they can rapidly deflate with an audible hiss [1, 5]. Characteristic findings on abdominal CT are collections of air adjacent to bowel lumen, with subserosal cysts commonly seen in small intestinal pneumatosis, but free peritoneal air has rarely been reported [1]. Complications associated with PCI occur in approximately 16.3% of cases and include intestinal obstruction or intestinal perforation [2].

This case highlights PCI as a benign entity and focuses on the role of patients’ clinical assessment in the management. It also emphasizes PCI as a cause of benign pneumoperitoneum. Although the patient did not meet the diagnostic criteria for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease that has been associated with PCI, we recognize the potential role of pulmonary emphysema in the etiology.