Introduction

Proctitis, an inflammatory syndrome arising in the rectum, is increasing in incidence. Both infectious and noninfectious etiologies may be implicated. Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), radiation, and diversion proctitis are some of the noninfectious causes [1]. On the other hand, infectious proctitis is also associated with nonsexually transmitted agents such as Escherichia coli, Shigella spp., Campylobacter spp., and Clostridioides difficile. Sexually transmitted agents, such as Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis, Treponema pallidum, and Herpes simplex virus (HSV) are increasing in prevalence, especially in men who have sex with men (MSM) [1-5].

C. trachomatis is a typical pathogen among patients with sexually transmitted anorectal infections [6]. Although lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV) is an uncommon cause of proctitis, more recently, outbreaks of sexually transmitted infections (STI) have been arising in western Europe. LGV can mimic more common conditions like IBD-related proctitis, other forms of infectious proctitis, and rectal adenocarcinoma or lymphoma [7].

A few cases of misdiagnosis of LGV-related proctitis as a rectal neoplasia were reported in the literature [7-14]. The similarity to rectal cancer presentation can delay the diagnosis, leading to high morbidity [7].

The diagnosis of rectal LGV requires a high index of clinical suspicion. An infectious etiology is usually low on the list of differential diagnoses for a rectal mass, but investigation for LGV should be considered more frequently, especially in high-risk patients such as MSM who are positive for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) [13, 14].

We present a case of LGV-associated proctitis in a middle-aged man with an unknown sexuality and HIV infection status, initially misdiagnosed as rectal neoplasia based on the clinic and imaging findings. The purpose of this case report is to increase the consciousness for rectal LGV amongst gastroenterologists, surgeons, and radiologists, to facilitate the early diagnosis and appropriate management of these patients.

Case Report

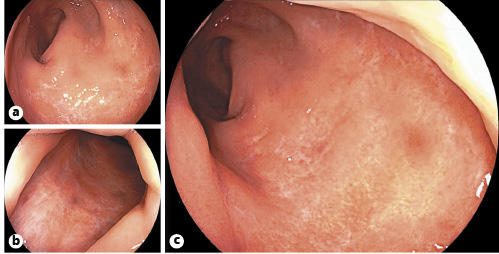

A 48-year-old Caucasian male with no significant previous medical history presented at the surgical emergency department of our hospital due to the suspicion of rectal neoplasia based on the results of an abdominopelvic computed tomography (CT) scan and pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) performed the day before at another institution. Imaging findings included a circumferential rectal wall thickening, with infiltration of the perirectal fat and invasion of the mesorectal fascia, associated with perirectal fat lymphadenopathy. A radiological diagnosis of a rectal malignant neoplasia staged as T4N2MX was given (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Coronal (a) and axial (b) contrast-enhanced abdominopelvic CT images and axial T1 (c) and T2 (d) pelvic MRI showing a diffuse circumferential rectal wall thickening associated with perirectal fat-stranding and lymphadenopathy.

The patient performed the previous exam due to complaints of anorectal pain, hematochezia, and constipation over the previous 2 weeks. He denied having fever, night sweats, abdominal pain, weight loss, or any other symptoms. He also denied abdominopelvic trauma, recent traveling to tropical destinations, anal sexual intercourse, and a personal or family history of colorectal cancer or IBD. He reported a family history of pancreas neoplasia (in a 2nd-degree relative) and cervical (a 1st-degree relative) and breast (2nd-degree relatives) cancer.

Physical examination was unremarkable and showed hemodynamic stability. Digital rectal examination identified a palpable circumferential rectal mass at 6-8 cm from the anal verge.

Laboratory results showed a white blood cell count of 8.5 × 109/L (N = 4.0-10.0), hemoglobin 14.3 g/dL (N = 13.0-17.5), and C-reactive protein 2.52 mg/dL (N < 0.50), with normal liver and renal function. Carcinoembryonic antigen was negative (3.5 ng/mL; N < 5.4).

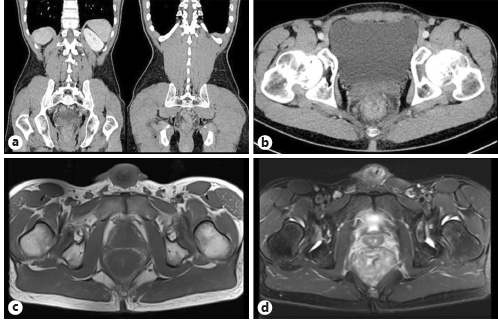

In view of the clinical and imaging findings, the patient was referred to rectosigmoidoscopy that revealed an extensive and circumferential ulceration of the rectal mucosa with elevated geographical borders and exudate. Some aphthoid erosions at the proximal limit of the endoscopic mucosal ulceration were also observed (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 Endoscopic images showing some aphthoid erosions at the proximal limit reached with the colonoscope (a), and a circumferential ulceration of the rectal mucosa with mucopurulent exudate (b, c).

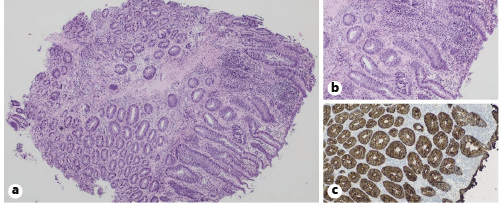

Biopsy specimens showed acute ulcerative proctitis with reactional changes of the crypts, goblet cell depletion, diffuse lymphoplasmocytic inflammatory infiltrate, and granulation tissue in the lamina propria. No microorganisms, spirochetes, or cytomegalic inclusion bodies were identified. Immunohistochemistry for Cytomegalovirus (CMV) was negative. There was no evidence of dysplasia or malignancy in these samples (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3 Histopathological images showing an acute mucosal ulceration, with reactional changes of the crypts, goblet cell depletion, diffuse lymphoplasmocytic inflammatory infiltrate, and granulation tissue in the lamina propria. HE. a ×40. b ×100. c Immunohistochemistry for cytokeratin AE1/AE3 was negative. ×100.

A full STI screening was performed. HIV-1 serology proved positive with CD4+ count of 251/mm3 (N = 700-1,100). Additionally, an elevated C. trachomatis IgA-specific antibody titer (52.000; N < 5.0) suggested LGV disease. The diagnosis was confirmed by C. trachomatis positivity on nucleic acid amplification testing on a rectal swab.

Other infectious causes of acute proctitis, including N. gonorrhoeae, T. pallidum, HSV, CMV, other fecal bacteria, and parasites, were excluded. When faced with these results, the patient ended up mentioning that he had had unprotected anal sex with men before the onset of symptoms.

A diagnosis of LGV-associated proctitis in a newly diagnosed HIV-infected man was made. The patient started treatment with doxycycline 100 mg twice a day for 21 days. He also underwent antiretroviral therapy with bictegravir, emtricitabine, and tenofovir for HIV infection.

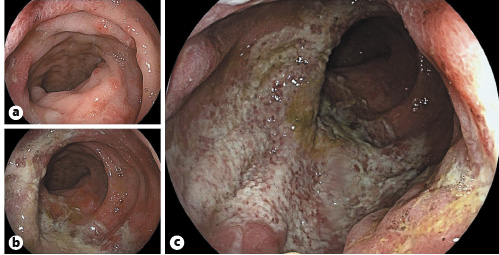

His symptoms dramatically improved after beginning antibiotic therapy. Two weeks later, rectosigmoidoscopy was repeated and there were clear signs of a progressive resolution of the ulcerative proctitis. A 3-month follow-up colonoscopy showed complete mucosal healing with scattered scars on the rectal mucosa (Fig. 4).

Discussion

In this clinical case study, we present a patient with acute proctitis, whose imaging findings raised the suspicion of rectal neoplasia. However, a detailed clinical history combined with endoscopic, histologic, and laboratory results suggested, instead, an infectious etiology, which led to a final diagnosis of LGV-proctitis in a newly diagnosed HIV-infected man.

Infectious proctitis is often sexually acquired. C. trachomatis is one of the most common agents of STIs [1, 2, 6, 15, 16].

C. trachomatis serovars A-K remain confined to the mucosa and are usually associated with a mild inflammatory rectal syndrome, requiring only 1 week of antibiotic therapy. In contrast, L strains are invasive, causing severe ulcerative proctitis, and can disseminate via underlying connective tissue and spread to regional lymph nodes, thus demanding a longer course of antibiotics [15, 17].

LGV is a STI caused by L serovars (L1-L3) of C. trachomatis by direct inoculation. The subvariant L2b is the causative strain in the majority of cases in Europe [17, 18]. Depending on the site of inoculation, LGV may determine inguinal disease (after inoculation via the genitalia or anal area) or anorectal syndrome (after inoculation via the rectum) [17].

Although an uncommon cause of acute proctitis, LGV has become a major cause of sexually transmitted proctitis, being endemic among MSM [5, 6, 17].

Inoculation via the rectum usually determines an isolated proctitis without lymphadenitis (in 83%). Patients can present with a wide range of symptoms including severe anorectal pain, rectal mucopurulent discharge, bleeding per rectum, tenesmus, and constipation due to mucosal and perirectal edema. In cases of severe inflammation, a prominent rectal wall thickening, rectal mass, or lymphadenopathy may occur, mimicking a rectal neoplasia [2, 5, 7, 9, 14, 17, 19].

There are no pathognomonic features of rectal LGV. The clinical, imaging, endoscopic, and/or histological findings may be similar to those caused by IBD and rectal adenocarcinoma or lymphoma. A high degree of clinical suspicion based on a detailed clinical history is essential to achieve the diagnosis of rectal LGV, particularly when a patient’s HIV status is unknown [5].

Imaging findings can show a diffuse rectal wall thickening, perirectal fat-stranding, submucosal edema, seminal vesicle enlargement, and pelvic and/or retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy in patients with LGV-proctitis. On the other hand, colorectal cancer can present as a focal or diffuse irregular wall thickening and can spread beyond the rectal serosa [7].

Endoscopic manifestations of LGV-proctitis can range from a mild mucosa erythema and aphtha to circumferential rectal ulcers, with friability and mucopurulent exudate, and tumor-like masses [17, 19, 20].

Histopathological findings of LGV-proctitis include mucosal ulceration, diffuse lymphohistiocytic infiltrate, hyperplasia of lymph follicles, crypt abscesses, or nonnecrotizing granulomatous inflammation [7, 17].

Definitive diagnosis of LGV-proctitis relies on the identification of the causative agent. Nucleic acid amplification tests are the current gold standard for the detection of chlamydial infections, with higher diagnostic performance in terms of sensitivity, specificity, and response-time than the previously used culture and immunological techniques [2, 16, 19]. Different types of samples can be used, such as anogenital lesion (ulcer exudate), rectal swab (when anorectal LGV is suspected), bubo aspirate (suspicion of inguinal LGV), or urine (when inguinal lymphadenopathy is suspected) [16]. If available, genotyping of C. trachomatis from the suspected clinical sample where C. trachomatis DNA was detected can also be performed to identify invasive genotypes (L1-L3) [17]. A presumptive LGV diagnosis can be made based on a C. trachomatis IgA-specific antibody test. A significant elevation in antibody titer, particularly IgA anti-major outer membrane protein antibodies, in combination with LGV symptomatology, strongly suggests a diagnosis of LGV [2, 17]. It is important to highlight that serologic testing has some drawbacks: diagnostic sensitivity and specificity are suboptimal, interpretation for LGV infection is not standardized, the absence of appropriate validation for rectal infections, and an inability to differentiate between past and current infection. Diagnosis of LGV infection based on cell culture methods is now outdated, because it is labor-intensive, expensive, and rarely available, besides having a suboptimal diagnostic sensitivity [17].

HIV infection is strongly associated with LGV transmission, with a prevalence of HIV among MSM with LGV ranging from 67 to 100% [17, 18]. Therefore, when a diagnosis of LGV is suspected, it is mandatory to test for HIV and other blood-borne viruses (hepatitis B and hepatitis C) if the serostatus is unknown [17].

Additionally, in case of proctitis in MSM, screening for other STIs is also recommended (including syphilis, gonorrhea, and HSV), as these may be the cause of the proctitis or coexist with LGV [16]. In about 20% of anorectal infections, > 1 sexually transmitted agent is observed [6].

LGV-proctitis can be associated with significant comorbidity, including fissure, fistula, abscess, scarring, and stricture. Patients with a clinical syndrome consistent with LGV-proctitis should thus immediately start treatment, even if no LGV diagnostic test is readily available [17]. LGV treatment consists of a course of doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 3 weeks [16, 17]. An alternative treatment regimen is azithromycin 1 g weekly for 3 weeks, but in rectal infections doxycycline achieves higher eradication rates [16].

LGV represents a compulsory notifiable disease. An essential requirement for the management of this STI includes the partner notification. Sexual partners from the last 3 months must be tested and, even if asymptomatic, should be treated with a course of doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 1 week [17]. Patients should abstain from any sexual contact until they have completed therapy [17].

In anorectal disease, symptoms should resolve within 1-2 weeks from the beginning of antibiotic therapy [17]. In case of complicated disease with fistulas or anal strictures, surgery or aspiration and drainage of lymph nodes may be needed [19].

LGV-associated proctitis, often undervalued, is a reemerging disease, which should always be considered a benign cause of rectal mass to avoid a delay in diagnosis and the development of complications. The diagnosis requires a high index of clinical suspicion, since clinical, imaging, endoscopic, and histological findings can mimic multiple benign or malignant conditions such as IBD, rectal adenocarcinoma, and lymphoma. Diagnosis becomes more challenging in patients with an unknown HIV status. A detailed clinical history, including sexual behaviors, is a vital step to achieve the final diagnosis.