Introduction

Colonoscopy is the standard examination for colorectal cancer screening and the investigation of colonic diseases [1]. Quality parameters are key to improve colonoscopy efficacy and safety, and factors such as an appropriate colonoscopy indication, the obtention of patients’ informed consent, an appropriate adenoma detection rate (ADR), and an adequate bowel cleansing are some of the several points that should be checked regularly to achieve a proper quality colonoscopy [1]. The European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) recommends a minimum of 90% procedures with adequate bowel cleansing [2], being that an inadequate bowel preparation is associated with the need to repeat colonoscopy, lower cecal intubation rates, unsatisfactory patient experience, and lower ADR [3].

Colon capsule (CC) is a minimally invasive procedure, with established indications, such as incomplete conventional colonoscopy, suspected lower GI bleeding, and inflammatory bowel disease [4], that is gaining recognition in the field of colorectal cancer screening [5]. For CC to be as viable as conventional colonoscopy, quality performance criteria are a matter of diligent importance and must be adapted and further evaluated. Regarding colon cleansing, our group recently took a step further by creating the Colon Capsule CLEansing Assessment and Report (CC-CLEAR) [6], allowing a standardized bowel cleansing reporting for CC, aiming to improve the quality of examinations as a support for clinical decisions and research reliability and validity. From a practical point of view, to achieve adequate colon cleansing in CC is challenging, since, for instance, intraprocedural actions aiming to improve bowel cleansing, such as “washing” and “aspiration” are not available when compared with conventional colonoscopy. An inadequate bowel cleansing will exponentially hamper the colonic lumen and mucosa visualization in CC setting. Therefore, being able to identify the subgroup of patients that will mostly benefit from an optimized and stricter cleansing protocol would be a benefit when striving to optimize the rate of adequate bowel cleansing in CC. The ability to improve the odds of obtaining adequate CC bowel cleansings will lead to lower need for repeated examinations and ultimately a better allocation of healthcare resources. We aim to define predictive factors for inadequate bowel preparation in CC, guided by the CC-CLEAR.

Methods

We designed a retrospective cohort study including consecutive patients submitted to CC endoscopy, in the Gastroenterology Department of a University-Affiliated Hospital. This department is a center of excellence for capsule endoscopy and highly experienced. The study protocol conforms to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki. All patients signed an informed consent form and consensual contraindications for CC procedure were respected.

Participants

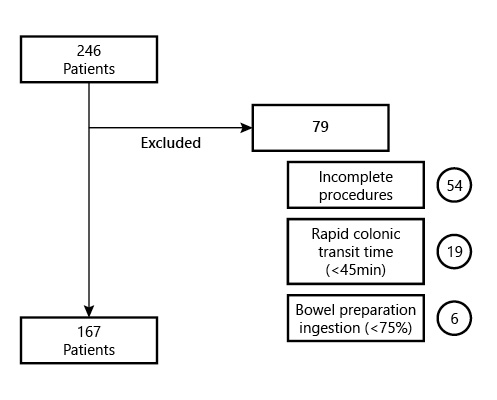

The participants included underwent CC from January 2015 until March 2021. The inclusion criteria were as follows: all adult patients (≥18 years old) who underwent CC endoscopy, regardless of clinical indication or comorbidities, with a complete procedure, meaning capsule exteriorization or at least visualization of the hemorrhoid pedicles within battery time. Exclusion criteria were pregnancy, known or suspected GI obstruction, incomplete procedures, CC with a colonic transit time inferior to 45 min, and patients not tolerating the ingestion of at least 75% of the bowel preparation regimen. Figure 1 represents the cohort’s exclusion criteria flowchart (Fig. 1).

CC Preparation

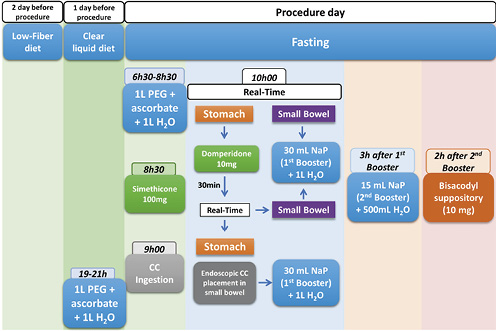

Bowel preparation was performed according to our center’s protocol [7-9]. Patients were instructed to have a low-fiber diet and ingest at least 10 glasses of water 2 days before the procedure. On the day before the procedure, a clear liquid diet was prescribed, as well as 1 L of polyethylene glycol (PEG) solution plus ascorbate followed by 1 L of water between 7 and 9 p.m. On the day of the procedure, another 1 L of this solution followed by 1 L of water was ingested (between 6:30 and 8:30 a.m.), and fasting was warranted afterward. Thirty minutes before capsule ingestion, patients were given 100 mg of simethicone. At 9 a.m., patients were instructed to ingest the capsule. One hour later, using the real-time viewing system, capsule progression to the small bowel was confirmed, and 10 mg of domperidone was administered if the capsule was still in the stomach. Thirty minutes later, capsule progression was assessed, and in the case of delayed stomach emptying, endoscopic capsule placement in the small bowel was performed. When the small bowel was reached, a booster of 30 mL of sodium phosphate solution (Fleet Phospho Soda; Casen-Fleet Laboratories, Madrid, Spain) was administered, followed by ingestion of 1 L of water; 3 h later, the second booster of sodium phosphate (15 mL) was administered, plus 500 mL of water. After another 2 h, if the capsule was not excreted, a bisacodyl suppository was given (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 The colon capsule cleansing protocol currently in practice in our Gastroenterology Department. CC, colon capsules; PEG, polyethylene glycol; NaP, sodium phosphate solution.

Capsule Reporting and CC-CLEAR Cleansing Scale

All procedures were performed with the PillCam® COLON 2 capsule (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA). Complete CC videos were reviewed by 2 independent experienced physicians (over 500 examinations) using the Rapid® Reader software version 9.0, in “twin head mode,” including both camera views from the CC displayed on-screen simultaneously at a rate of 8-15 frames per second [10, 11]. CC bowel cleansing was classified according to the CC-CLEAR scale [6]. Colon was divided into 3 segments as follows, right-sided, transverse, and left-sided colon, keeping in mind the main colon landmarks (hepatic and splenic flexures), and each segment was classified according to an estimation of the percentage of mucosa clearly visualized (0 points, <50%; 1 point, 50-75%; 2 points, >75%; 3 points, >90%), taking into account solid debris, clarity of liquid, and bubbles, which could compromise an adequate visualization. The overall cleansing classification was based on the sum of each segment’s score, grading between inadequate (0-5 points), good (6-7 points), and excellent (8-9 points). If any segment presented a classification of 1 or less, the overall classification given was inadequate, independent of the overall score punctuation.

Data and Variable Definition

The primary outcome variable was an inadequate bowel cleansing according to the CC-CLEAR cleansing scale (overall scoring of less than 6 points or at least 1 segment scoring less than 2 points). Co-variables included demographic characteristics, namely, age (collected as continuous variable and nominal variable, according to the cut-off 65 years old) and gender, grade of education (according to the cut off 9th grade of school education). We also assessed cohort comorbidities, including, multiple comorbidities (more than 3 chronic diseases), previous diagnosis of dementia, diabetes mellitus, obesity (IMC ≥30), previous history of abdominal surgery and impaired mobility (diagnosed by an expert physician, and meaning the need of external help for daily basis activities). We also assessed chronic constipation (diagnosed by an expert gastroenterologist, according to clinical history and physical examination [12, 13], keeping in mind the ROME criteria [14]), previous inclusion in a cleansing protocol, and CC and/or colonoscopy reporting inadequate bowel cleansings (regarding the latter, according to the Boston Bowel Preparation Scale [15]). Regarding drugs, we considered poly-medication (more than 3 drugs taken on a daily basis), taking chronic laxatives, opioid drugs, calcium channel blockers, and antidepressants (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, and tricyclic antidepressant). We also evaluated whether the patient was admitted to the hospital at the moment of CC, CC indication, CC-related complications, colonic transit time (meaning the time from the first image of the cecum until the exteriorization or at least visualization of the hemorrhoid pedicles, measured in minutes) and CC-CLEAR cleansing scale (measured as continuous variable - the final overall scoring per capsule; and as nominal variable - inadequate versus adequate classification, the latter considering all capsules not meeting the criteria for inadequate cleansing).

Statistical Analysis

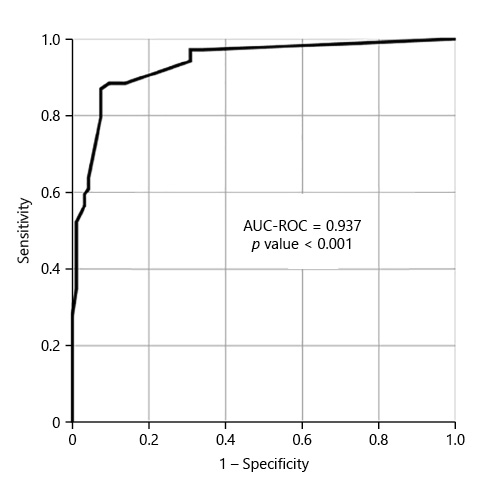

Categorical variables were described using absolute frequencies and percentages, while continuous variables were described using medians and interquartile ranges. We compared the frequency of inadequate bowel cleansing according to the different collected variables. Categorical variables were analyzed using Fisher’s exact test or χ2 test, as appropriate. Continuous variables were analyzed using Student’s t test or Mann-Whitney U test. Independent variables with statistical association with the outcome variable (p < 0.005) in univariable analysis were simultaneously tested in a multivariable logistic regression model. In order to avoid the inclusion of an excess number of variables in relation to our sample size (with 71 inadequate bowel cleansings, and considering a need for 10-15 events per covariate, no >5 covariates should be simultaneously introduced in the model), we included 5 covariates, keeping in mind clinical value, easy applicability and the crude univariate odds ratio. We assessed the performance of the multivariate final model for the prediction of inadequate bowel cleansing by means of a receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) - we determined the area under the curve (AUC-ROC) and the respective 95% CI. Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS version 26.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). All reported p values are 2-tailed, with p < 0.05 indicating statistical significance.

Results

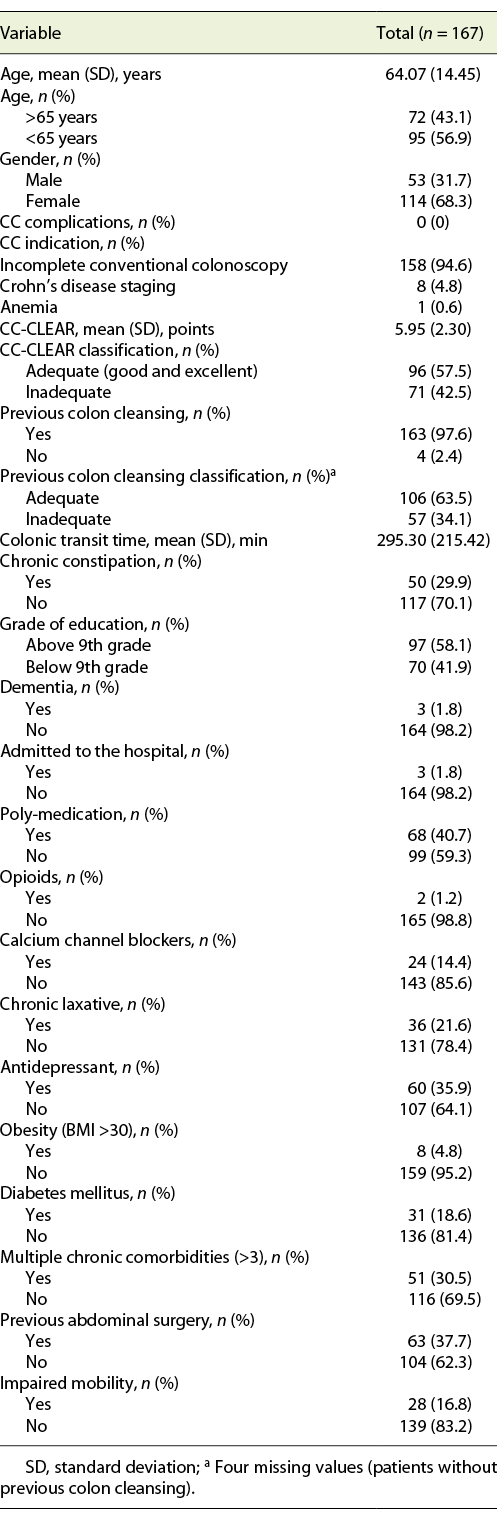

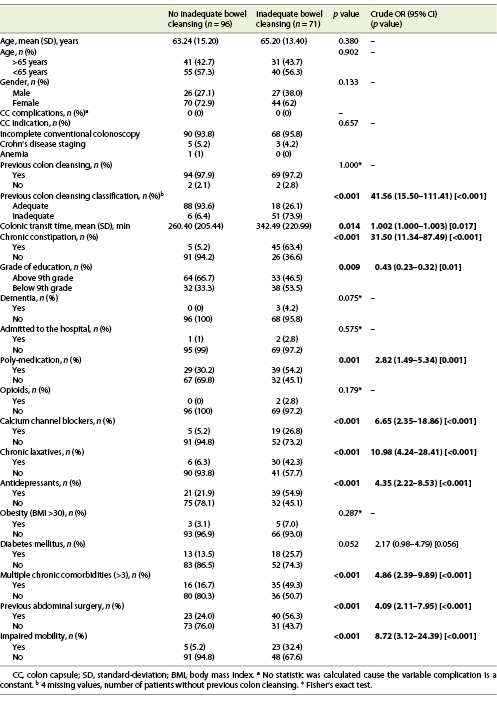

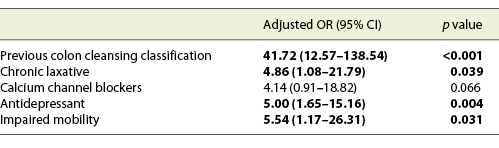

We included 167 consecutive CCs, from 2015 to 2020. Sixty-eight percent (n = 114) were female, with a mean age of 64 years. The main indication for CC was incomplete colonoscopy, in 158 patients (94.6%). The CC cleansing was graded as good or excellent in 96 patients (57.5%) and as inadequate in 71 (42.5%), according to CC-CLEAR. Table 1 lists the descriptive analysis of all variables included. Table 2 lists the results of the univariable analysis and the crude odds ratio comparing patients who presented an inadequate bowel cleansing versus the remaining. The following variables presented statistically significant association with inadequate bowel cleansing (Table 2): previous inadequate colon cleansing classification (p < 0.001; OR crude 41.56 [95% CI 15.50-111.41], p value < 0.001); chronic constipation (p < 0.001; OR crude 31.50 [95% CI 11.34-87.49], p value < 0.001); grade of education (p = 0.009; OR crude 0.43 [95% CI 0.23-0.42], p value 0.01); poly-medication (p = 0.001; OR crude 2.82 [95% CI 1.49-5.34], p value 0.001); calcium channel blockers (p < 0.001; OR crude 6.65 [95% CI 2.35-18.86], p value < 0.001); chronic laxative (p < 0.001; OR crude 10.98 [95% CI 4.24-28.41], p value < 0.001); antidepressant (p < 0.001; OR crude 4.35 [95% CI 2.22-8.53], p value < 0.001); multiple chronic comorbidities (p < 0.001; OR crude 4.86 [95% CI 2.39-9.89], p value < 0.001); previous abdominal surgery (p < 0.001; OR crude 4.09 [95% CI 2.11-7.95], p value < 0.001); impaired mobility (p < 0.001; OR crude 8.72 [95% CI 3.12-24.39], p value < 0.001); and colonic transit time (p = 0.014; OR crude 1.002 [95% CI 1.000-1.003], p value 0.017). Five co-variables were included in the multivariate logistic regression model, keeping in mind clinical value, easy applicability, and the crude univariate odds ratio. Table 3 lists the co-variables included in the multivariate logistic model. The following variables remained statistically associated with the outcome (inadequate bowel cleansing): previous inadequate colon cleansing (OR adjusted 41.72 [95% CI 12.57-138.57], p value < 0.001); chronic laxative (OR adjusted 4.86 [95% CI 1.08-21.79], p value = 0.039); antidepressant (OR adjusted 5.00 [95% CI 1.65-15.16], p value = 0.004) and impaired mobility (OR adjusted 5.54 [95% CI 1.17-26.31], p value = 0.031). By means of a ROC, we tested the performance of the model. The model presented an excellent discriminative power and optimal accuracy when tested against the outcome variable, as indicated by the area under curve (AUC) of the ROC in Figure 3 (AUC-ROC 0.937 [95% CI 0.899-0.975], p value < 0.001).

Table 2 Results of the univariable analyses and crude odds ratio assessing the potential association between patients’ demographic, clinical, and laboratory variables and the occurrence of inadequate bowel cleansing according to CC-CLEAR

Table 3 Results of the multivariable logistic regression analyses assessing the association between patients’ co-variables and the occurrence of inadequate bowel cleansing according to CC-CLEAR in the colon capsule

Discussion

An adequate bowel cleansing is the cornerstone for a high-quality colonoscopy, impacting the examination diagnostic efficiency and being crucial for optimal colonic visualization [1, 2]. For a reliable CC, an adequate colon cleansing is even more indispensable, since intraprocedural actions aiming to improve bowel cleansing, such as “washing” and “aspiration” are not available when compared with conventional colonoscopy. We are also unable to modify the patients’ position, insufflate the colonic lumen, and, since CC is not operator dependent, we lack motion control over the twin-head camera direction. These conditions make an inadequate bowel cleansing in CC a factor that exponentially hampers overall examination quality when compared with conventional colonoscopy. Therefore, we can only rely on preprocedural modifiable aspects to optimize CC bowel cleansing.

We included 167 consecutive CCs, 71 (42.5%) graded with inadequate bowel cleansing, according to CC-CLEAR. The comparison with the literature reported cleansing rates is biased, mainly due to the overwhelming subjectivity associated with previous CC bowel cleansing classifications. For instance, Spada et al. [16] reported CC inadequate preparation in 57.5% of cases and Kastenberg et al. [17] in 24.1% of cases. For conventional colonoscopy, the rates of inadequate bowel cleansing are also widely variable and go from 12 up to 50% [18-22].

With the guidance of the CC-CLEAR to optimize result reliability [6], we were able to report independent predictive risk factors for an inadequate colon cleansing in CC. A previous inadequate colon cleansing, impaired patient mobility, and chronic usage of antidepressants and laxatives were the independent factors that showed a correlation towards an inadequate bowel cleansing in CC. The final model including these variables showed an excellent discriminative power and optimal accuracy in predicting inadequate bowel cleansing, by means of an AUC-ROC of 0.937 (CI 95% 0.899-0.975; p value < 0.001). The literature is scarce in the topic of predicting inadequate bowel cleansing in CC. However, several studies have been published regarding the prediction of inadequate bowel preparation for conventional colonoscopy, reporting similar predictive factors. In their multicenter observational study that included 1,032 patients, Fuccio et al. [18] reported that meetings with physician, educational instructions in bowel preparation, admission to gastroenterology unit, split-dose regimens, the usage of 1 L PEG-based preparation, and the ingestion of at least 75% of bowel purge were associated with adequate bowel cleansing. On the other hand, a bedridden status, constipation, diabetes mellitus, use of antipsychotic drugs, and 7 or more days of hospitalization were associated with inadequate bowel cleansing. Dik et al. [19] studied a cohort of 1,331 colonoscopies, and concluded that an ASA score ≥3, chronic use of tricyclic antidepressants and opioids, diabetes mellitus, chronic constipation, previous abdominal surgery, previous inadequate bowel preparation, and current hospitalization were factors associated with inadequate bowel cleansing, reporting a good model discriminative power with an AUC-ROC of 0.77. Yadlapati et al. [20], from a cohort of 524 patients, reported that a lower income, chronic opiate or tricyclic antidepressant, afternoon colonoscopy, an ASA class ≥3 and nausea/vomiting were related to inadequate preparation. Gimeno-Garcia et al. [21] developed a predictive model for inadequate bowel preparation, from a cohort of 541 patients, based on antidepressants, comorbidity, constipation, and previous abdominal surgery (AUC-ROC of 0.72). Garber et al. [22], concluded based on 8,819 colonoscopies that opiate use, colonoscopy after 12:00 p.m., and solid diet the day before colonoscopy are related to inadequate bowel cleansing. They recommend avoiding opiates before colonoscopy, performing colonoscopy before noon, and maintaining patients on a liquid diet to reduce inadequate bowel cleansing rates in 5.6%. In conclusion, and concerning the predictive model proposed in this study, including the variables previous inadequate colon cleansing, impaired mobility, chronic usage of antidepressant and laxative, it is reasonable to assume that there is a predictive factor overlap when compared with conventional colonoscopy studies.

A rather consistent predictive factor is chronic constipation, and we deem it necessary to explain the rationale behind the option to withdraw the diagnosis of chronic constipation from our final model. Chronic constipation is a very common gastrointestinal disorder with a prevalence of almost 20% in the general population [23], and as stated above, it is associated with higher rates of inadequate bowel cleansing. Guo et al. [24] reported that more than 1/3 of patients with functional constipation had inadequate bowel cleansing. Nevertheless, chronic constipation is very challenging to diagnose [12], and to avoid variable overlap, since a large proportion of patients with chronic constipation consume laxatives, we opted to include chronic laxative usage instead, as it is an easier and more reliable variable to evaluate, whilst still selecting patients at a higher probability of inadequate bowel cleansing.

We propose an accurate model to select patients for an optimization of the CC preparation protocol, recognizing, however, that this optimization is per se a controversial topic.

PEG-based purges seem to be safer and more efficient when compared to non-PEG ones. In conventional colonoscopy, low volume (2 L) PEG also seems to be as efficient as large volume purges (4 L) and is better tolerated by patients [25]. In the setting of CC, controversy surrounds the efficacy of low-volume PEG purgatives. Argüelles-Arias et al. [26], in a head-to-head comparison study with a 4 L PEG protocol, proposed the addition of ascorbic acid to a 2 L PEG purgative, reporting better rates of adequate preparations and complete procedures. Vuik et al. [5], in a recent systematic review, reported a rate of CC adequate colon cleansings up to 92% for 4 L PEG formulations compared to 70% for low-volume PEG protocols. The current CC ESGE guidelines still recommend classic 4 L PEG formulations [4]. For CC to remain a patient appealing procedure, the balance between cleansing protocol tolerability and efficacy is thin, but nevertheless, when striving for optimal CC cleansings, conventional high-volume PEG-based purges could be a reasonable recommendation. Since CCs are usually early morning examinations, the split-dose regimen is the most efficient and tolerated protocol timing to recommend [27]. Regarding diet, a low-fiber diet a day before the conventional colonoscopy seems to be as efficient as a clear liquid diet for cleanliness levels and encompasses better patient adhesion and satisfaction [28]. However, evidence is scarce concerning CC, and a clear diet the day before the procedure is associated with a higher diagnostic yield [4]. In selected cases, the recommendation of a clear diet for 2 or more days before the procedure may be a strategy to implement [16]. Adjunctive drugs are proven essential to improve overall cleanliness and capsule expulsion, and some are already a part of our regular preparation protocol, namely, ascorbic acid, simethicone (100 mg), prokinetics (domperidone 10 mg), a booster of 45 mL of sodium phosphate solution, as well as bisacodyl suppository on the procedure day [29]. In patients at higher risk for inadequate CC cleansing, it would be reasonable to assume a benefit from the implementation of laxatives a day or 2 before the procedure, such as, bisacodyl or senna tablets. Spada et al. [16] suggested that the inclusion of 4 senna tablets the day before procedure was safe and effective. In conventional colonoscopy, a bisacodyl (10 mg) suppository administered 2 h before the start of bowel cleansing allowed the reduction of PEG purgative volume with similar cleansing efficiency and increasing patient compliance [30, 31]. Specifically, regarding chronic obstipation, the inclusion of an oral lactulose solution (30 mL) 1 day before colonoscopy [32], or rectal fleet enemas (sodium hydrogen phosphate and disodium hydrogen phosphate) prior to oral purgative may increase colon cleansing [33].

Additionally, and regarding modifiable aspects, we recommend implementing educational sessions, guided by physicians, to approach the cleansing protocols. In a recent meta-analysis, Gkolfakis et al. [34] concluded that education over the bowel preparation regimen improves adequate bowel preparation rates, from 50 up to 77%.

Captivating patients’ adhesion towards the cleansing preparation should also be a priority. Adjunct agents to improve patients’ experience may have a role in increasing palatability, without hampering cleansing levels, namely, substituting water for orange juice, pineapple juice or green tea, and the inclusion of gum chewing and menthol candy drops [35].

It is key to understand that the ideal bowel preparation regimen for CC remains to be determined, and no single intervention has been proven to be optimal. We may only assume that combined optimization strategies will potentially improve the final CC cleanliness.

We acknowledge some limitations of the present study, namely its retrospective design, the single hospital center nature and the absence of an external validation for comparison. We recognize that further multicentric, prospective validation of the CC-CLEAR, and its influence in daily clinical practice will strengthen our results.

However, this article also presents several strong points. First, it raises awareness towards the importance of establishing quality criteria for an optimal capsule colonoscopy. To our knowledge, this is the first study addressing the topic of inadequate colon cleansing prediction in the setting of CC, based on the new cleansing reporting scale, the CC-CLEAR, a quantitative objective scoring index to enhance objectivity when assessing the quality of bowel preparation in CC. We herewith provide an accurate model that identifies patients at a higher risk for inadequate cleansing examinations, which paves the way for tailored optimization of bowel preparation protocol for CC in those settings.