Introduction

Pancreatic pseudocysts are fluid, homogeneous, and encapsulated collections [1] that may occur a few weeks after an episode of acute pancreatitis, on chronic pancreatitis due to an acute exacerbation or ductal disruption, and, more rarely, due to ductal disruption secondary to trauma [2].

In 4.5% of the cases, generally in the setting of chronic pancreatitis, these collections give rise to fistulous tracts to the pleural cavity, causing an exudative pleural effusion [3].

Case Description

A 61-year-old man was admitted to the emergency department with an insidious history of shortness of breath, malaise, loss of weight (7 kg), and anorexia in the previous 6 weeks. He denied chest pain, cough, fever, abdominal pain, or diarrhea. Past medical conditions included arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus type 2, and dyslipidemia. Chronic medications included acetylsalicylic acid, valsartan, atorvastatin, and metformin. He denied smoking and re-ported an alcohol intake of 20 g a week. He denied past history of acute pancreatitis or trauma and his family history was irrelevant.

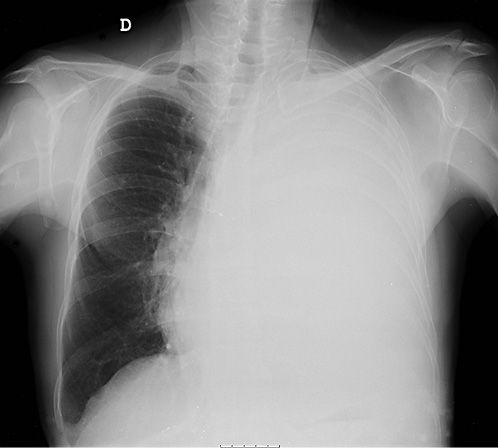

On physical examination, his vital signs were stable and he had no signs of respiratory distress. On pulmonary evaluation, the patient exhibited dullness to percussion and absent breath sounds on the left hemithorax. Blood studies were unremarkable. Chest radiograph showed hypotransparency of the whole left hemithorax (Fig. 1).

These findings were compatible with a pleural effusion of un-known etiology, causing respiratory distress. After a diagnostic and therapeutic thoracocentesis, the patient was discharged and a medical reevaluation was scheduled to the following week.

One week later, the patient was feeling well. Laboratory results regarding pleural fluid analysis revealed an exudate, with a raise on amylase (2,070 U/L) and bilirubin (6.2 mg/dL) levels and low levels of triglycerides and adenosine deaminase. Cytology of the fluid was negative for malignant cells.

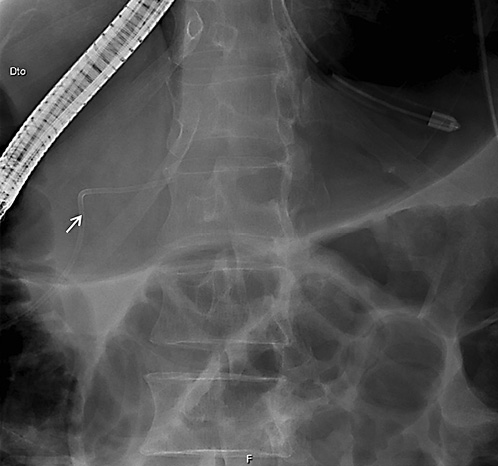

In light of these findings, a thoracoabdominal computed tomography (CT) was performed, revealing a homogeneous and fluid peripancreatic collection with a well-defined enhancing rim, close to the upper border of the pancreatic body, with a maximum diameter of 48 mm, which exhibited two fistulous tracts: one to-wards the spleen and another to the diaphragm (Fig. 2). No abnor-malities were found on the pancreatic parenchyma, gallbladder, and bile ducts and there were no abdominopelvic adenopathies.

Fig. 2 Thoracoabdominal computed tomography showing a peripancreatic collection with a fistulous tract towards the spleen (right image, white arrow) and another to the diaphragm (left image, white arrow).

On abdominal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), this collec-tion showed no signs of suspicion, namely septations or mural nodules with enhancement, and no changes on the pancreatic parenchyma were identifiable, nor dilatation of the duct of Wirsung. The diagnosis of a pancreatic pseudocyst with a pancreaticopleural fistula (PPF) and a pancreaticosplenic fistula was made.

Four weeks later, the patient was readmitted to the emergency department with similar complaints, exhibiting a relapse of the pleural effusion on chest radiograph. After multidisciplinary dis-cussion, conservative treatment with therapeutic thoracocentesis, octreotide, and an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatogra-phy (ERCP) for Wirsung evaluation and pancreatic stenting was proposed.

On ERCP, the Wirsungogram identified a point of ductal leak-age in the body of the pancreas, with contrast spreading to the middle of the column (most likely to the pseudocyst lumen) (Fig. 3). Pancreatic sphincterotomy and placement of a double-flanged straight 5-Fr plastic stent with 9 cm (the longest one avail-able in the unit) in the duct of Wirsung, up to the ductal disruption site (Fig. 4), were performed.

Fig. 3 Wirsungogram performed on the first endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, revealing a ductal leakage in the body of pancreas (white arrow).

Fig. 4 Radiograph showing the pancreatic plastic stent after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.

Four months after discharge, the patient reported no relapse of the initial symptoms. An abdominal MRI was repeated, revealing an almost complete reabsorption of the collection, resolution of the fistulous tracts and no abnormalities on the pancreatic parenchyma or in the duct of Wirsung.

Elective ERCP was also undertaken to remove the pancreatic stent and to evaluate Wirsung patency, which had no signs of leak-age after contrast injection (Fig. 5). A prophylactic short plastic stent was placed during 1 week, to diminish the risk of potential post-ERCP pancreatitis.

On a 5-month follow-up, the patient is feeling well, with no pleural effusion on chest radiograph.

Discussion

This report describes a case of an idiopathic pancreatic pseudocyst, complicated with a PPF and a pleural effusion. In fact, this patient had no history of trauma or acute pancreatitis and did not have any known risk fac-tors for chronic pancreatitis, nor pancreatic parenchyma alterations on MRI.

PPF is a very rare entity, thus optimal approach of this uncommon condition has not been evaluated in large studies [4].

Wronski et al. [5] have proposed an approach based on MRI findings. Medical management (thoracocentesis and somatostatin analogs to reduce the fistula output) is reserved for patients with no ductal alterations. Endo-scopic management, with stent placement to bridge the ductal disruption site, and thus enabling closure of the fistula, is indicated for patients with ductal disruption in the head/body of the pancreatic or distal ductal stenosis. Cases of complete ductal disruption, proximal ductal ob struction, and failure of medical/endoscopic treatment should prompt for a surgical approach. Furthermore, relapse of the PPF is not infrequent, which also demands for surgical intervention [6].

In this case, ERCP identified a ductal disruption in the body of the pancreas. Pancreatic sphincterotomy and stent placement, combined with medical manage-ment, allowed fistula closure and no relapse of the pleural effusion, as well as reabsorption of the pancreatic pseudocyst. Few studies have reported optimal results with this more conservative approach, with resolution of the ductal disruption in almost every case, as the authors describe in this case report [7, 8]. However optimal duration of the stent placement is still controversial ]9]. An important point to discuss on the diagnostic work-up of this patient was the absence of an endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) to evaluate a fluid peripancreatic collection in a patient with no history of acute or chronic pancreatitis, trauma, and pancreatic surgery. Although the abovementioned imagiologic features were highly predictive of a pancreatic pseudocyst, EUS outperforms both CT and MRI in visualizing pancreatic cystic lesions and to distinguish between benign and malignant ones [10]. Cyst fluid sampled by EUS-guided fine needle aspi-ration could also aid on the differential diagnosis in this intriguing scenario [11].

The relevance of this case lies not only in its rarity but also as it highlights the importance of a multidisciplinary approach to optimize patient management.