Introduction

The management of head and neck cancers is often demanding, requiring radical surgical resections with complex reconstructive surgery and/or radiotherapy. Pharyngoesophageal stenosis is frequent sequelae that can lead to swallowing dysfunction, malnutrition, and reduced quality of life. Ultimately, it can progress to complete esophageal obstruction (CEO) with aphagia.

Surgical approaches attempting to re-establish esophageal luminal patency, such as esophagectomy with colonic interposition, gastric transposition, or myocutaneous flap repair, are technically complex and associated with perioperative complications [1]. As a result, endoscopic techniques have been attempted as less invasive and traumatic therapeutic alternatives. A combined anterograde-retrograde rendezvous procedure with recanalization and dilatation to restore the esophageal continuity through endoscopy was first described by van Twisk et al. [2]. Since then, some case reports and case series for lumen restoration in CEO using a combined anterograde-retrograde endoscopy have been published [3-19] and a recent systematic review and meta-analysis has confirmed its safety and efficacy [20].

The aim of this case report is to describe our approach of endoscopic anterograde-peroral and retrograde-transgastric rendezvous with transillumination and fluoroscopy for esophageal recanalization in a patient with CEO following surgery and chemoradiation due to a neck cancer who had been aphagic for more than 5 years.

Case Report

A 70-year-old patient came to our outpatient clinic, in the patient’s own words, “asking for a miracle.” He had been submitted to multiple surgeries and chemoradiation due to a recurrent squamous cell carcinoma of the hypopharynx, ending in a major cervical amputation, construction of a neopharynx, and definitive surgical closure of the esophagus. After years being fed through a gastrostomy, he had not lost his hope to be able to eat again.

Eight years before, the patient, a heavy smoker and social drinker, was diagnosed with a cT2N1 pyriform sinus squamous cells carcinoma. He underwent chemoradiation therapy, complicated by bilateral neurosensorial hearing loss, and implantation of a hearing aid.

One year later, a left epiglottic tumoral recurrence was histologically confirmed. The patient underwent a total laryngectomy with left hemi-thyroidectomy and implantation of a voice prosthesis (Provox®).

After additional radiation therapy, he developed an esophageal stricture and a new tumoral recurrence at the hypopharynx. He then underwent subtotal pharyngectomy, an orostomy, and an esophagostomy with deltopectoral flap. Recovery was complicated with carotid artery exposure and necrosis of the flap requiring an urgent repeated surgery. A myocutaneous pectoralis major flap and a free cutaneous flap were used for wound closure, and surgical reconstruction was later performed: pharyngoplasty with a myocutaneous flap of the left pectoralis major, closure with the right deltopectoral fasciocutaneous flap and tracheoplasty, closure of the proximal esophagus, and placement of a gastrostomy for definitive feeding.

When the patient presented 5 years later, he was under oncological surveillance and the cancer was in remission. After detailed explanation, he consented for an attempt at endoscopic reconstruction. A combined endoscopic examination was undertaken by 2 endoscopists under general anesthesia to evaluate the pharyngeal and the superior esophageal closures and the distance between them: (1) using a therapeutic endoscope (Olympus GIF1T190, Hamburg, Germany) through the mouth up to the neopharynx pouch, and (2) using an ultra-slim (Olympus GIFP190) endoscope in a retrograde approach through the gastrostomy, passing the stomach and the cardia up to the proximal portion of the esophagus.

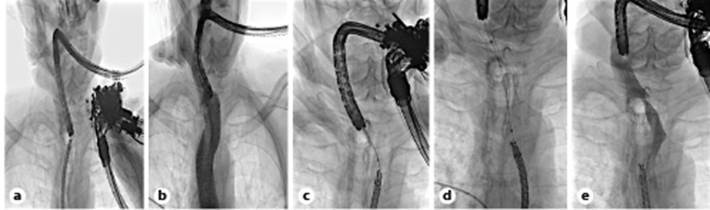

Fluoroscopically, before and after contrast injection through both approaches, it was possible to confirm that the distance between both ends was <10 mm (Fig. 1a). Transillumination was evident (after turning off the light of the slim scope) and an imprint on the closed proximal esophagus was visible from the esophageal lumen when manipulating a closed biopsy forceps from the pharyngeal pouch (shown in Fig. 2a).

Fig. 1 Fluoroscopic views: short distance between both scopes (a); same as a after contrast injection (b); dilation of the tract (c); stent placement before (d) and after (e) contrast injection.

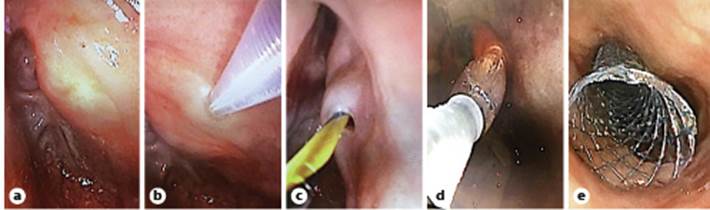

Fig. 2 Endoscopic views: transillumination of the therapeutic scope observed in the superior portion of the esophagus (a); puncture of the neopharynx with the Zimmon® knife (b); passage of the Jagwire (c); dilation of the tract (d); stent placement (e).

Using a Zimmon® diathermic needle (COOK Medical, Winston Salem, NC, USA) and under fluoroscopic and endoscopic control both proximally and distally (to visualize the bulging at the time of needle compression), we punctured (using a pure cutting current) through the neopharynx into the distal esophagus (shown in Fig. 2b). A 0.035-inch Jagwire was then placed (Fig. 2c) and grasped with a snare through the working channel of the ultra-slim endoscope. Dilation of the tract was then performed using a MaxforceTM through-the-scope balloon (6 mm/4 cm, Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA, USA; shown in Fig. 1c, 2d) and a fully covered biliary WallFlexTM stent 60 × 10 mm (Boston Scientific) was placed under endoscopic and fluoroscopic control (shown in Fig. 1d, e, 2e). Antibiotic prophylaxis with amoxicillin/clavulanic acid 2.2 g intravenous was administered before the procedure and in the following 48 h.

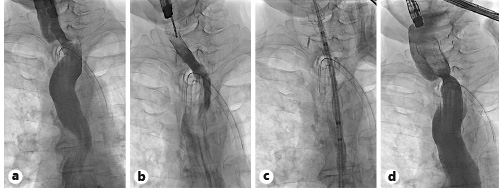

One week later, a second endoscopy was performed. After confirming the adequate position of the stent and free progression of the contrast through its lumen (Fig. 3a), the stent was removed (Fig. 3b) using a rat tooth grasping forceps. The upper part of the re-permeabilized segment was marked with a clip and a partially covered esophageal UltraflexTM esophageal stent 18 × 23 × 120 mm (Boston Scientific) was implanted (shown in Fig. 3c, d) over a metallic Savary guidewire.

Fig. 3 Fluoroscopic views: contrast injection through the WallflexTM stent, documenting good contrast progression (a); WallflexTM stent removal with a foreign-body forceps (b); UltraflexTM stent placement (c); contrast injection through the UltraflexTM stent, documenting good contrast progression and no complications (d).

Oral intake with a liquid diet was then started and quick progression to pasty food was possible, with excellent tolerance. Four weeks later, a tailored fully covered esophageal WallstentTM was placed inside the previous stent, and 1 week after both stents were removed without complications.

One month after the removal of the stents, the patient complained of slight dysphagia for pasty food and a dilatation up to 20 mm with a CRETM balloon (Boston Scientific), with complete disappearance of the waist, was performed at the level of the neopharynx-esophagus stenotic anastomosis. Regular endoscopic surveillance will be maintained to control/treat the luminal stenosis of the neoesophagus. Logopedic treatment is ongoing to further improve deglutition/swallowing.

Discussion

Endoscopy has been increasingly reported as a modality for re-establishing patency of an obstructed esophagus. Endoscopy provides a precise tool for characterizing the obstruction, assessing its degree and breadth, and, using the combined anterograde-retrograde rendezvous approach, provides a controlled re-anastomosis of proximal and distal ends of the esophagus.

The majority of CEO cases treated endoscopically were due to radiotherapy [3-7, 10-18, 21, 22]. The distinctiveness of this case is related to the fact that recanalization was made between a neopharynx, created with a myocutaneous flap, and a closed esophagus, with disappearance of the upper esophageal sphincter. In addition, the patient had been submitted to radiotherapy and had a longstanding aphagia of around 5 years. As such, we would anticipate that although the mechanical obstruction was treated, the functional behavior of this new feeding route would be unpredictable. Even if no risk of aspiration existed due to the presence of a tracheostomy, it was possible that due to the sustained damage of several structures involved in deglutition, the patient could have lost the ability to swallow. Interestingly, this was not the case, even before starting re-education. The clinical success on refeeding was impressive and it was achieved without any complications.

In general terms, the recanalization method of an esophageal disruption depends on the length of the gap between both ends, measured as the distance between the endoscopes on fluoroscopy. Blind anterograde puncture should be avoided due to risk of perforation or inadvertent injury to surrounding critical structures in the neck and chest.

If there is a short gap between the scopes (<3 cm), a combined anterograde-retrograde endoscopic rendezvous procedure offers good visualization and a safe technique. In this technique, the proximal and distal ends of the stricture are endoscopically reached and the puncture is performed after achieving transillumination. Endoscopists can use a biopsy forceps [5, 11, 16, 18, 23], needle-knife [13, 15, 21], or endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle puncture [8, 10, 11, 19, 22]. Then, dilation with a balloon is performed and a self-expanding metal stent can be placed, to calibrate the stricture, and/or a nasogastric tube, to ensure access to the stricture for the next procedure and prevent leakage. In our case, the procedure was mainly guided by endoscopic view under fluoroscopic control. The distance between the scopes was extremely small. Furthermore, we checked the position of the 2 endoscopes and the direction of the needle at several time points, and in different planes, using different radiographic axes to ensure that we were following the best route and avoiding the creation of false paths. If the gap was longer, a computed tomography scan could be performed before puncturing, to confirm the absence of vessels or other structures in the area. Stent placement [8, 10, 15, 17, 22] is not consensual as it is not proven to reduce the need for subsequent dilations and may result in serious complications [10]. We placed a stent to maintain luminal patency after creating the neoesophagus, since it did not pose the risk of airway compression and could reduce the risk of leakage and promote re-epithelization.

In esophageal disruptions in which there is a long CEO (>3 cm) and there is no transillumination, the success of endoscopic recanalization is poorer due to the lower feasibility of having 2 endoscopes approaching each other and aligned in close proximity. Surgery is an option (or a combined endoscopic-surgical approach, requiring a head and neck surgeon [8]) but often not viable in patients with multiple comorbidities and prior history of surgery and/or irradiation of this area. As such, new techniques are being developed. The recently reported Per-Oral Endoscopic Tunneling for Restoration of Esophagus (POETRE), using endoscopic submucosal tunneling with combined anterograde-retrograde endoscopic dilatation, may be an alternative [22, 24]. A neoesophagus can be created through submucosal tunneling into obstructions previously felt to be too long for a standard rendezvous procedure. Another interesting option would be to use magnets to create a path. Indeed, magnetic compression anastomosis (magnamosis) has also been successfully tested in cases of long-gap esophageal atresia, for creating esophagoesophageal anastomosis [25].

A limitation of this recanalization technique is that it requires long-term commitment of the patient to repeat follow-up, as re-establishing luminal patency usually is only the first step in a series of interventions to maintain the esophageal lumen. Residual stenosis is frequent and has not always been successfully treated, especially in obstructions at the level of the larynx or pharynx, as in this case [9].

This case adds to the growing evidence in support of the endoscopic rendezvous approach as an effective method to achieve recanalization in complex and long-standing cases of aphagia, including due to CEO after neck surgeries with reconstruction of the neopharynx and closure of the esophagus. This has now become part of the multidisciplinary armamentarium for such difficult cases.