Introduction

Klebsiella pneumoniae is a gram-negative pathogen that is a common cause of severe infections, such as pneumonia and urinary tract infections, as well as liver abscess, endophthalmitis, and meningitis [1]. Pyogenic liver abscess (PLA) caused by K. pneumoniae is an emerging infectious disease worldwide [2-4]. The highest incidence of such abscesses is reported in Asia [5]. In particular, PLA caused by serotype K1 K. pneumoniae has increased in incidence and can affect healthy adults without underlying diseases [6]. A PLA is a serious life-threatening condition, with a mortality rate of 6-14% [7, 8]. The prognosis of PLA has improved with the increased availability of imagological diagnostic methods, such as ultrasound (US) and computed tomography (CT), as well as the use of effective antibiotics. Early antibiotic treatment is essential to reduce morbidity and mortality [9]. In fact, the mortality rate of PLA was >50% before 1980 and decreased to 6.3% by 2011 [10].

Endogenous endophthalmitis (EE), a rare but devastating disease, is the most common and serious septic complication of PLA [11, 12]. EE is an infection inside the eye involving the vitreous and/or aqueous humor. EE, especially when associated with PLA caused by K. pneumoniae, can lead to poor outcome in terms of visual acuity (VA) [11, 12]. Little information on risk factors for EE in PLA patients is available.

We herein report a case of EE probably associated with PLA caused by K. pneumoniae in whom VA did not improve after treatment. We discuss the clinical characteristics and compare the case with past reports.

Case Report

A middle-aged woman presented to the emergency department of a secondary hospital with a 4-day history of fever (maximum temperature 39.5°C), malaise, and nausea. She also reported right eye pain in the last 24 h and a disturbance in VA. She had no underlying diseases but was taking various dietary supplements.

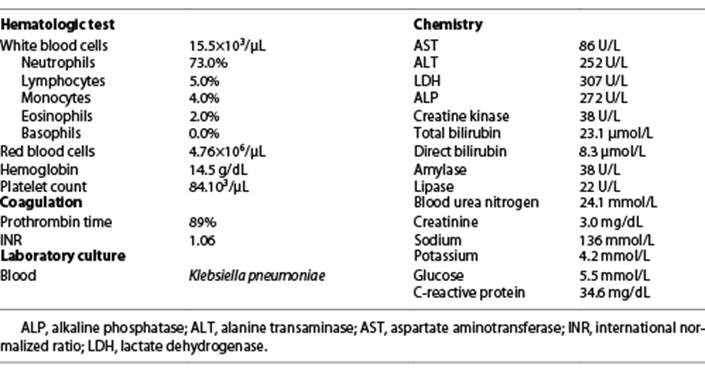

On admission, the patient was alert, her body temperature was 38.0°C, and her blood pressure was 88/50 mm Hg. Her right eye exhibited erythema and eyelid swelling. Her right eye VA was strongly impaired, and only her light sense was maintained. The results of heart, respiratory, and abdominal examinations were normal. Laboratory analysis revealed an inflammatory status, with a white blood cell count of 15,500/μL, a C-reactive protein level of 34.6 mg/dL, and acute renal failure with a creatinine level of 3 mg/dL. A few days later blood cultures grew K. pneumoniae that was resistant only to fosfomycin. Table 1 summarizes the laboratory findings on admission. Chest X-ray showed elevation of the right hemidiaphragm.

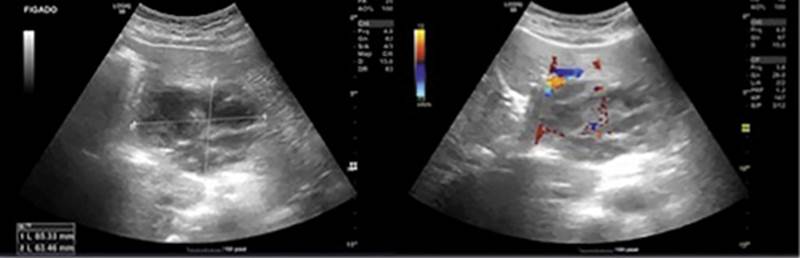

Abdominal US demonstrated a 6.7-cm solid hypoechogenic nodule in the left liver possibly representing an abscess or a hydatid cyst. Abdominal CT was subsequently performed to clarify the US findings and a diagnosis of hydatid cyst was presumed. After being evaluated by an internal medicine physician and an ophthalmologist, the patient was hospitalized. Sepsis with no determined origin and uveitis of the right eye were assumed and empiric antibiotic therapy with ceftriaxone 2 g i.v. and topical dexamethasone 1 mg/mL for uveitis was initiated.

Four days later, after hemodynamic stabilization and due to worsening eye complaints (worsening of pain with more erythema and eyelid swelling without recovery of VA), the patient was transferred to a tertiary hospital for observation and guidance by ophthalmology. At this point she had exuberant chemosis of the conjunctiva, decompensated cornea, hypopyon, as well as dense and organized vitreous echoes, suggestive of endoph thalmitis. She was advised about the poor prognosis regarding the recovery of VA. Eye exudate was collected for culture, later showing a negative result, and a new blood culture was also taken, with a negative result as well. An intravitreal antibiotic injection (vancomycin 0.1 mL and ceftazidime 0.1 mL) was performed, followed by vitrectomy. The patient was subsequently medicated with phenylephrine 100 mg/mL, dexamethasone 1 mg/mL, dorzolamide + timolol 20 mg/mL + 5 mg/mL, oxytetracycline 5 mg/g, brinzolamide 10 mg/mL, and cyclopentolate 10 mg/mL.

Four days later, despite an improvement in some liver tests (AST 43 U/L, ALT 32 U/L, ALP 336 U/L, total bilirubin 8.6 µmol/L), she maintained elevated inflammatory parameters and fever. A new abdominal US was performed, which revealed a nodular lesion with slightly ill-defined, lobulated contours in the left liver lobe, with no other alterations. This lesion had mixed characteristics with echogenic and anechogenic areas. Once more, the following diagnostic options were considered: hydatid cyst in stage 4, abscess, and cystic tumor (cystadenoma). There was no dilation of the bile ducts (Fig. 1).

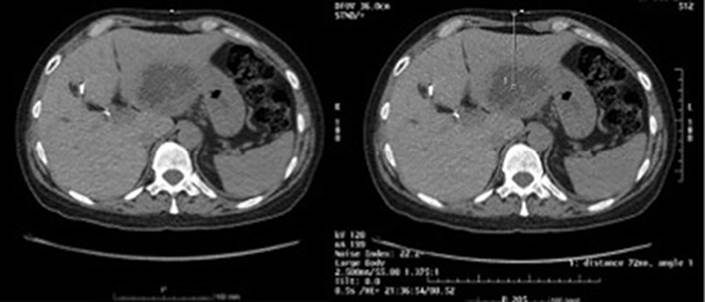

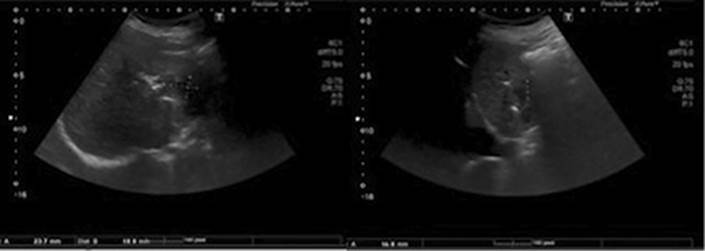

By now it was decided to perform a second abdominal CT, which revealed (1) dilation of the intrahepatic bile ducts, with left aerobilia and spontaneously hyperdense material in the right bile ramifications, which seemed to correspond to intrahepatic stones and (2) an organized liquid collection of lobulated contours, multiseptated and with a thickened wall measuring 6.8 × 6.3 cm of greater axis in the lateral segments of the left liver lobe. This collection presented parietal and septal enhancement and was suggestive of intrahepatic abscess (Fig. 2). In view of these findings, metronidazole 500 mg 8/8 h was added to ceftriaxone 2 g i.v. and a CT-guided drainage of the liver abscess with a 10-Fr catheter was performed and a sample was sent to culture, but the results were negative. Four days later a follow-up US revealed a small residual collection (Fig. 3) and the drain was removed. With these data it was possible to assume a diagnosis of EE of the right eye with its origin in the liver abscess.

The patient completed a total of 4 weeks of antibiotic therapy (20 days of ceftriaxone 2 g i.v. then switched to oral cefuroxime 500 mg 12/12 h and metronidazole 500 mg 8/8 h) and presented a good clinical evolution concerning the liver abscess. While still in hospital, she underwent ERCP in order to eliminate biliary lithiasis shown on the CT scan. The procedure went without complications. However, regarding endophthalmitis, she showed improvement in the eye pain complaints but did not recover VA.

The patient remains in follow-up in external consultation with imaging surveillance and periodic blood analyses. There was absence of recurrence or other complications until a current 15-month follow-up.

Discussion and Conclusion

PLA, especially when caused by K. pneumoniae, has a severe prognosis [13]. K. pneumoniae is often found in the intestinal flora of healthy individuals and can infect the liver via the portal system or intestinal epithelium [14]. K. pneumoniae is the most common bacterial isolate to cause metastatic infections [15]. Patients with K. pneumoniae hepatic abscess commonly present with fever, right upper quadrant tenderness, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, leukocytosis, as well as elevated ALT, AST, ALP, and bilirubin. Approximately 13% of patients with a primary liver abscess develop metastatic infections, with the most common manifestations being endophthalmitis, meningitis, and cerebral abscess [5, 6, 16]. Park et al. [17] in 2015 showed that the presence of another systemic infection (OR = 6.13, p = 0.002), K. pneumoniae infection (OR = 4.29, p = 0.018), an abscess in the right superior segment (OR = 4.9, p = 0.041), and underlying diabetes mellitus (OR = 3.17, p = 0.048) were significant risk factors for EE in PLA patients.

Extrahepatic infections are occasionally the first manifestations, and a high degree of suspicion for liver abscesses is essential to avoid delays in diagnosis [18]. This is reflected in the finding that the median duration of symptoms before diagnosis is a week, with a further quarter of patients having symptoms between 1-2 weeks [19-21].

In the present case, the patient had been presenting a 4-day history of fever, malaise, and nausea, but it was the ocular manifestations that motivated the visit to the emergency department. She only went to the hospital when she already had visual impairment.

In patients with signs of sepsis and no obvious source of infection, an abdominal US must be performed as soon as possible. However, CT imaging of the liver is the most sensitive method for diagnosing an abscess [22]. CT findings suggestive of an abscess by K. pneumoniae include a single solid and/or multiloculated lesion, with unilobar involvement [23]. In the present case a liver lesion was identified but misinterpreted initially as a hydatid cyst. Even so, systemic antibiotic treatment was implemented with ceftriaxone 2 g i.v., although it was only optimized with metronidazole a few days later, when an imagological reevaluation suggested a hepatic abscess. CT imaging was essential for diagnosis, but the first image interpretation favored a hydatid cyst. Hydatid cyst is a differential diagnosis of liver abscess; regarding imagological findings it usually presents as a fluid density cyst, with frequent peripheral focal areas of calcification, which usually indicates no active infection if completely circumferential. Septa and daughter cysts may be visualized. The water-lily sign indicates a cyst with a floating, undulating membrane, caused by a detached endocyst. It may also show hyperdense internal septa within a cyst showing a spoke-wheel pattern. The fluid is of variable attenuation, depending on the amount of proteinaceous debris. It may show dilated intrahepatic bile ducts due to compression or rupture of the cyst into bile ducts [24]. Liver abscesses generally appear as peripherally enhancing, centrally hypoattenuating lesions. Occasionally they appear solid or contain gas. The gas may be in the form of bubbles or air-fluid levels. Segmental, wedge-shaped, or circumferential perfusion abnormalities, with early enhancement, may be seen [25]. A second evaluation of the first CT scan would probably be useful. Additionally, CT revealed the etiology of the abscess since intrahepatic biliary stones were identified. Taking into account the existence of calculi of the intrahepatic biliary tree, aerobilia, dilation of the bile ducts, and elevation of ALP, this is the most likely cause for the occurrence of intrahepatic abscess and the patient was proposed to undergo an ERCP in order to eliminate biliary lithiasis shown on the CT scan.

Association with thrombophlebitis and hematogenous septic complications are also more frequently observed in patients with PLA caused by K. pneumoniae than with other pathogens [23]. As patients are susceptible to septic pulmonary emboli, chest X-ray is recommended. Multiple, ill-defined peripheral round opacities on X-ray indicate the need for further imaging, commonly chest CT. As recommended, our patient underwent an X-ray, which did not reveal changes suggestive of thromboembolism.

In terms of microbiological diagnosis, a K. pneumo niae isolate taken from a blood or liver abscess with the hypermucoviscous phenotype is suggestive of an invasive K. pneumoniae strain, and the attending clinician should be notified as soon as possible [26].

K. pneumoniae endophthalmitis classically presents with swelling, redness, sudden onset of blurred vision, and pupillary hypopyon [12]. The diagnosis is confirmed by positive swab microbiology or blood cultures [3, 27]. The visual outcome tends to be poor, with sight limited to hand motion if light can be perceived. Good vision at diagnosis is a predictor of better visual outcomes [28]. Our patient had all the criteria of a bad prognosis. Initial blood cultures were positive for K. pneumoniae but swab microbiology was negative. This is understandable since the patient was already on antibiotic treatment when the specimen was collected.

The correct diagnosis of EE is often delayed or the disease is even initially misdiagnosed. In 45% of patients, ocular symptoms were the initial manifestation of K. pneumoniae septicemia, in which a liver abscess was subsequently discovered. Fulminant rapid progression of endophthalmitis was the typical clinical course [12]. Most patients with EE have a poor visual outcome. This is generally attributed to the highly virulent organism as well as delayed recognition. Yang et al. [12] reported that a more than 2-day delay in the initiation of treatment for EE resulted in a severe visual outcome. Chen et al. [29] in 2019 also reported that poor initial VA (OR = 4.6, 95% CI 1.6-13.4, p = 0.004), positive K. pneumoniae aqueous or/and vitreous humor culture (OR = 4.9, 95% CI 0.9-26.4, p = 0.059), and the diagnosis of EE before PLA (OR = 5.1, 95% CI 1.6-26.6, p = 0.007) were important risk factors for poor visual outcomes. However, sometimes useful vision can be preserved in patients treated with intravitreal antibiotic injections and/or vitrectomy.

In our case, the duration of ocular symptoms before the diagnosis of EE was not shorter than 2 days, and the VA was already impaired at admission. Although the patient was treated with intravenous antibiotics before the correct diagnosis of EE, we considered that these treatments were incomplete. As seen in our case, some patients were reported to have a rapid deterioration of VA; this sudden aggravation of VA should be taken into consideration when managing patients.

Our empirical antibiotic choice and the duration of treatment are similar to those reported elsewhere in the literature [19, 30]. The duration of treatment is determined by the resolution of fever, neutrophilia, and liver abscess. In the case presented, a 4-week course of antibiotic therapy (cephalosporin plus metronidazole) was completed. Cephalosporins have a good and fast penetration to the aqueous humor of the eye, cerebrospinal, synovial, and pericardial fluid [19, 30]. The liver abscess itself requires early percutaneous drainage, like in our case, but sometimes surgical treatment is needed.

This case report reminds us that a liver abscess should be thought of in patients with high fever and markedly high C-reactive protein. Physicians should recognize the potential for extrahepatic septic metastases and their complications, and a strong multidisciplinary therapy should be administered immediately to prevent PLA complications, including EE.