Case Report

A 78-year-old woman presented with watery diarrhea and weight loss - 20 kg, 33% of body weight - in the previous 5 months. She denied fever or relevant epidemiological context. Her previous history was unremarkable.

Blood analysis showed anemia (hemoglobin 8.4 g/dL), leukocytosis with neutrophilia and high C-reactive protein (73.8 mg/L). Fecal analysis was negative for microbiological, parasitological and Giardia presence; fecal calprotectin was unchanged. Magnetic resonance enterography described normal small bowel and colon appearance, mesenteric fat densification and prominent mesenteric ganglia.

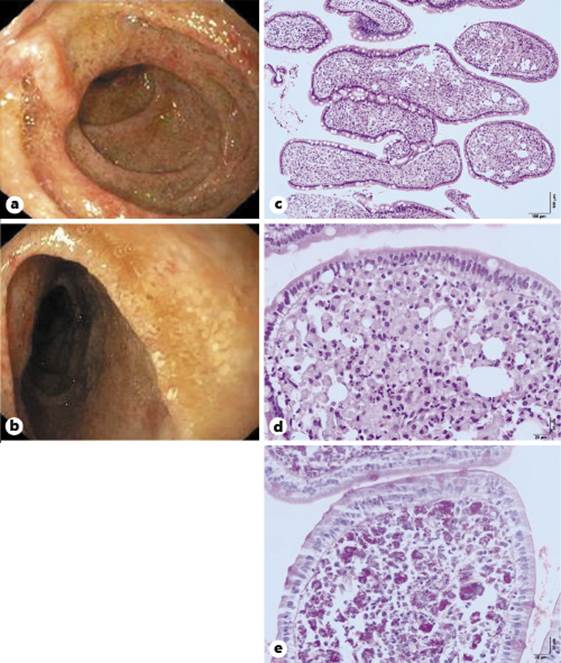

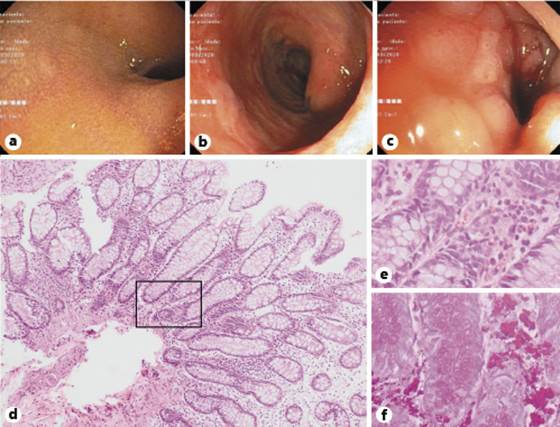

Upper endoscopy revealed enlarged duodenal folds, lymphangiectasias, focal hyperemia and friability of the duodenal mucosa (Fig. 1a, b). Ileocolonoscopy revealed continuous edema, hyperemia and friability of the distal ascending colon, associated with erosions and superficial ulcers, as well as a reduced distensibility (Fig. 2b, c). There were no endoscopic alterations in the remaining segments, including the terminal ileum (Fig. 2a). Histological examination of duodenal (Fig. c-e), ileal and ascending colonic samples (Fig. 2d-f) identified the presence of foamy macrophages, with periodic acid-Schiff (PAS)-positive intracytoplasmic granules, which were Ziehl-Neelsen-negative. Despite having no clinical neurological involvement,Tropheryma whippleiDNA was detected in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF).

Fig. 1 Upper endoscopy findings and histological examination.a,bEnlarged duodenal folds, lymphangiectasias and focal hyperemia and friability of the duodenal mucosa (c-e) fragment of duodenal mucosa, showing villous thickening due to macrophage cell infiltrate with clear and mucinous cytoplasm, with PAS+ intracytoplasmic granules. Hematoxylin and eosin, ×100 (c) and ×400 (d), and PAS stain, ×400 (e).

Fig. 2 Lower endoscopy findings and histological examination.aNormal mucosa of the terminal ileum.bHyperemia, edema and erosions of the ascending colon mucosa.cEdema, friability and reduced distensibility of the ascending colon mucosa.d-fFragment of colon mucosa, showing infiltration of the chorion by foamy macrophages, with PAS+ intracytoplasmic granules. Hematoxylin and eosin, ×100 (d) and ×400 (e), and PAS stain, ×400 (f).

The patient completed a 14-day course of once daily 2 g intravenous ceftriaxone, followed by a 12-month course of twice daily 800 + 160 mg oral trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, which is currently under way. Diarrhea resolved in the first weeks of antibiotic therapy, and full weight recovery occurred after 4 months.

Whipple’s disease is a very rare and potentially fatal systemic disease. It usually develops over the course of many years in genetically predisposed patients. The classic presentation is characterized by diarrhea and weight loss, often preceded by joint complaints. Other symptoms include abdominal pain, low-grade fever and adenopathy. The diagnosis is based on characteristic findings in duodenal or jejunal biopsies. Although typical, the presence of foamy PAS-positive macrophages remains nonspecific and may be seen in other infections, particularly in immunocompromised patients, such asMycobacterium avium,Rhodococcus equi, extrapulmonary pneumocystosis, leishmaniasis and histoplasmosis [1]. Ziehl staining is helpful to excludeMycobacteriumbut a definite diagnosis impliesT. whippleiidentification by a second diagnostic test: immunohistochemistry or identification of bacterial DNA with polymerase chain reaction. The search for the bacteria in the CSF was of diagnostic value in our case. Yet, it is recommended in all cases to accurately evaluate central nervous system (CNS) involvement, which occurs in about half of the patients. In those cases, treatment should include an antibiotic with good penetration of the blood-brain barrier such as co-trimoxazole and should aim PCR negativity, since CNS disease may progress or relapse and is one of the major death causes [2].

Few works have addressed the endoscopic findings in Whipple’s disease, which are generally limited to the small bowel [3]. Colonic involvement was rarely described in the literature [4]. A very recent work reports the case of a child with chronic bloody diarrhea and an endoscopic appearance resembling ulcerative colitis, whose histological evaluation was diagnostic for Whipple’s disease [5]. In our work, we document small bowel mucosal appearance, as well as colonic endoscopic changes.