Introduction

Dyspepsia represents multiple and heterogeneous symptoms originating in the gastroduodenal area, including pain or discomfort in the epigastric region, gastric fullness, early satiety, nausea, or belching [1, 2]. Using a broad definition, dyspepsia is common in the adult population, with an estimated prevalence of 10-21% world-wide and an annual incidence of 1-5%, being more frequent in women [1-3].

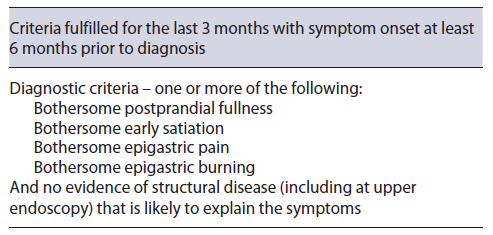

Dyspepsia can be associated with medication, infections, and several diseases, either systemic or locoregional [1, 4]. Given that symptoms are not a good differentiator between organic or functional dyspepsia (FD), an accurate diagnosis of FD requires exclusion of a structural disease in accordance with Rome IV criteria (Table 1) [2]. Also, in the latest Maastricht and Kyoto consensus [5, 6], infection with Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is considered a cause of dyspepsia (termed H. pylori associated dyspepsia) and so it should be included in the differential diagnosis [2, 5, 7, 8]. Even if dyspeptic symptoms can be caused by several etiologies, a majority of patients pre-senting with dyspepsia, after thorough search, will be diagnosed with FD [1, 4, 8, 9].

FD can be divided in two major subcategories: epigastric pain syndrome (EPS) - mostly related with pain and burning in the epigastric region - and postprandial distress syndrome (PDS) - associated with postprandial fullness and early satiety. It is estimated that PDS is more common than EPS (57-61% vs. 8-18%, respectively) and about 21-35% of patients will have an overlap of symptoms [3, 10]. The main objective in this subdivision is to differentiate the underlying pathophysiology and to adjust medical therapy, although there are conflicting data about the relevance of this subdivision in terms of treatment response and prognosis [11].

Several studies have highlighted multiple factors associated with and possibly causing FD, including environmental exposures, immunological mechanisms (duodenal inflammation, duodenal eosinophilia, and cytokines), impaired gastric emptying or accommodation, and visceral hypersensitivity or altered brain response to pain.

Even though the pathophysiology of FD has been a subject of recent discoveries, a multifactorial etiology is likely [1, 12, 13].

The heterogeneous and complex mechanisms behind FD make a targeted treatment difficult and a nonpharmacological approach with lifestyle recommendations is still the first-line treatment. Even so, an increased interest in drugs targeting FD’s pathophysiology has been rising [4, 11, 12, 14-16].

Some of the older treatment options for FD are acid-suppressing drugs, neuromodulators and prokinetics [4, 7, 8, 11, 16]. But new treatment options are just around the corner, including new drugs targeting old pathways and old drugs aiming newly discovered pathways (e.g., with the use of immunosuppressive drugs or histamine-1 receptor antagonists) [17-19]. In this work, we aim to revisit some of the pharmacological treatment options for FD, both well stablished and new, highlighting the efficacy, dosage, duration of therapy, and possible adverse effects (AE).

Methods

A nonsystematic review was performed using a bibliographic search on MEDLINE using the keywords: “functional dyspepsia”; “non-ulcer dyspepsia”; and “treatment”. Articles written in English, Spanish, or Portuguese were reviewed. Systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and guidelines published in the last 5 years were preferred.

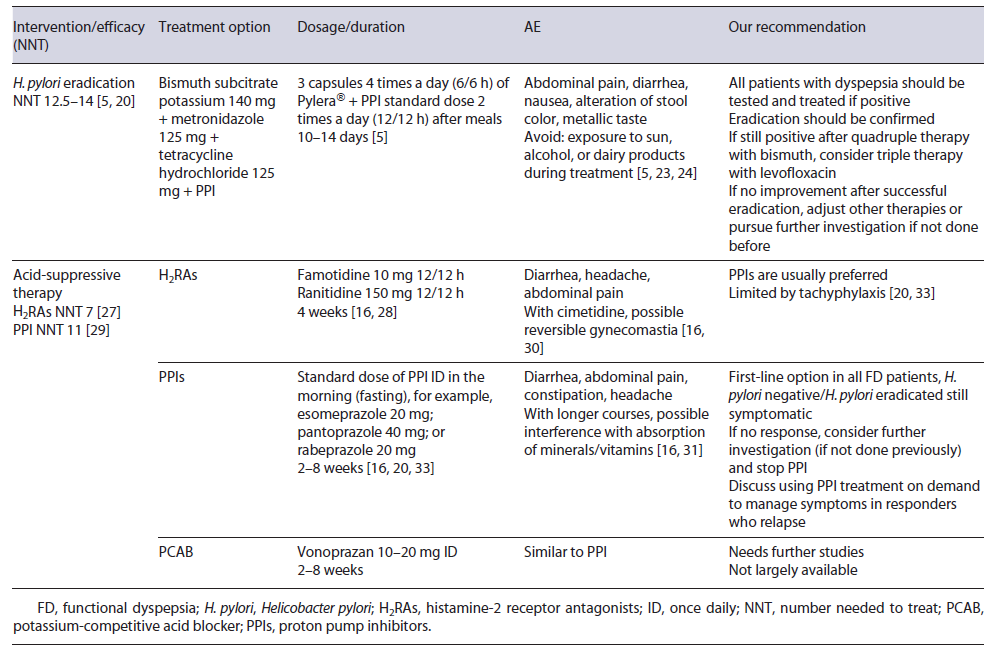

Treatment of H. pylori-Associated Dyspepsia

H. pylori infection is an organic cause of dyspepsia and should not be considered as FD [5]. As such, eradication is the first-line treatment in dyspeptic patients with H. pylori. Indeed, sustained symptomatic improvement is significantly increased after eradication (absolute difference of 10% when compared to placebo or acid suppression therapy; number needed to treat [NNT] 12.5-14), even if it can take up to 6-12 months to be reached [5, 6, 20]. Eradication therapy must have in account personal history (including previous attempts of eradication, recent prescription of antibiotics, and allergies) and local resistance to antibiotics. In settings where primary clarithromycin resistance exceeds 15%, quadruple therapy with or without bismuth is recommended [5].

In Europe, a recent study showed a high prevalence of clarithromycin and metronidazole resistance (21.4% and 38.9%, respectively) [21]. Portugal has also a high prevalence of clarithromycin and metronidazole resistance (42% and 25%, respectively), and thus quadruple therapy with bismuth and proton pump inhibitor (PPI) twice daily (BID) during 10 days is recommended [5, 22]. Most common AE include abdominal pain, diarrhea, and nausea, but they are usually mild and compliance is higher than 90% (need to discontinue of 2-3%) [23, 24]. It is important to alert patients to expected side effects: darker stools, metallic taste, diarrhea, and increased skin photo-sensitivity. Alcohol and dairy products should be avoided. Eradication rates >90% have been shown across Europe [23-25]. Assessment of the patient’s symptoms after eradication will tell if there is any need to pursue further investigation since a substantial percentage of patients will remain symptomatic after successful eradication and will, in the absence of other disease, be ultimately classified as having FD [5, 16].

Current Treatment Options for FD

Acid-Suppressive Drugs

PPIs and Histamine-2 Receptor Antagonists

Although FD is not usually related to an increase in acid output, an increased sensitivity to acid is a potential mechanism in FD [16, 20]. Waters et al. [26] showed that a PPI course decreases duodenal eosinophil counts in a small group of FD patients, which is also a possible explanation for symptom improvement with PPIs in FD.

The two main types of acid-suppressive drugs are PPIs and histamine-2 receptor antagonists (H2RAs). H2RAs decrease acid output by inhibiting histamine H2 receptors in parietal cells, and a 2006 Cochrane meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) reported a benefit in FD over placebo with a NNT of 7 [27]. The main issue with these trials is the inconsistent definition of FD (with inclusion of patients with GERD in older trials) [28].

PPIs act by an irreversible covalent ligation with the H+/K+-ATPase proton pump, and they have been one of the most used drugs in FD [17, 20, 26, 29]. A 2017 Cochrane meta-analysis showed that PPI therapy was statistically more effective than placebo with a NNT of 11 [29]. No difference was found between low and standard dose of PPIs and it is unlikely that higher doses have a superior effect [20, 29]. Differences among response in PDS or EPS have controversial results, but in this meta-analysis no difference was found. Comparison between PPIs and H2RAs failed to show statistically significant differences between the two in ameliorating symptoms, but methodological classification of FD in older studies might be an issue [20, 29].

H2RAs have some AE like diarrhea, headache, and cimetidine specifically has a weak anti-androgen effect. The development of tachyphylaxis is also a problem as the effectiveness of this class may decrease with continued use [16, 30].

PPIs, on other hand, are relatively safe in short courses but can also cause diarrhea and abdominal pain. The increased risk of some infections, for example, by Clostridioides difficile might be worrisome. In longer courses, PPI-induced hypochlorhydria interfere with the absorption of vitamins (B12), drugs, or ions (calcium, iron), but the majority of recommendations is against routine evaluation of these ions [16, 29, 31].

Treatment with a standard dose of H2RA BID with a 4-week course is an option in FD [32]. With PPIs, the standard dose is usually employed, and esomeprazole and rabeprazole may be more appropriate where the prevalence of PPI extensive metabolizers is high, namely, in Europe and North America [5]. Most studies use a 2- to 8-week treatment duration, but therapy can be extended if needed [7, 16, 20, 29]. On-demand therapy (with a repeated course) in patients with intermittent symptoms is also an option after initial success. Deprescribing PPIs may be challenging and both dose tapering and abrupt discontinuation can be considered [33]. Due to their safety profile and higher acid-suppressing capacity, PPIs are indicated as the first-line therapy for all FD patients in recent guidelines, but more high-quality studies are needed [20, 34, 35].

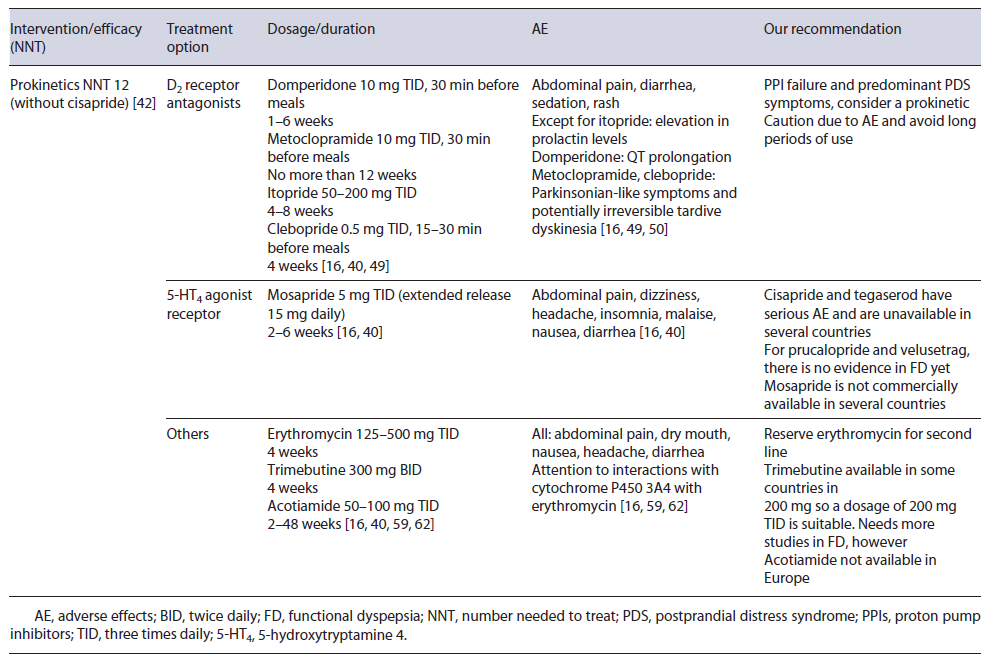

Potassium-Competitive Acid Blocker

Vonoprazan is an established potassium-competitive acid blocker and competitively blocks the potassium-binding site of the H+/K+-ATPase proton pump [36]. It appears to produce a stronger and more sustained acid suppression than PPIs, with a recent meta-analysis demonstrating that vonoprazan is more effective than PPIs in patients with severe erosive esophagitis [37]. It is given once daily (ID) in a dose of 10-20 mg and AE appear to be similar to PPIs, but they are not available in Western countries [38]. Regarding FD, clinical improvement was assessed in a small retrospective study with a 48.8% rate of symptomatic improvement, but further studies are needed [39, 40]. Table 2 summarizes medical treatment options for FD regarding H. pylori eradication and acid-suppressive drugs.

Table 2 Current medical treatment options for FD regarding H. pylori eradication and acid-suppressive drugs

Prokinetics

Gastric dysmotility is a proposed mechanism for FD through impaired gastric accommodation (present in 15-50% of FD patients) and delayed gastric emptying. Thus, prokinetics are considered one of the treatment options, especially in PDS [7, 16, 34, 36]. Korean guidelines, for instance, assume that prokinetics can be useful as a first-line therapy in PDS [41].

In 2019, a meta-analysis showed that FD patients treated with prokinetics had a statistically significant reduction in global symptoms compared to placebo (NNT of 7; 12 when cisapride was removed from analysis) [42]. However, heterogeneity among pharmacological classes and older studies may limit generalizability [16, 36, 42, 43].

Most prokinetic drugs act either as a dopamine 2 (D2) receptor antagonist, 5-hydroxytryptamine 4 (HT4) receptor agonist, or motilin agonist. More recently, the acetylcholine pathway has been modulated [16, 41, 42]. Domperidone, metoclopramide, levosulpiride, clebopride, and itopride are some of the most prominent D2 receptor antagonists.

Domperidone is one of the most frequently used prokinetics [42, 44, 45]. Older studies demonstrated its efficacy in FD, but the risk of bias may be an issue [41, 43].

One of the most feared AE is the potential for QT prolongation, estimated in up to 6-10% with a baseline electrocardiogram being recommended [46-48]. A normal dosage is 10 mg three times daily (TID) between 2 and 4 weeks [41]. Even so, longer periods (6-12 months) and higher doses (up to 20 mg TID) have been used in gastroparesis without major AE, but a follow-up electrocardiogram during treatment is advised [46-49].

Metoclopramide is a D2 receptor antagonist and a 5-HT4 agonist/5-HT3 receptor antagonist that can pass the blood-brain barrier and cause extrapyramidal symptoms in 1-6% and hyperprolactinemia [4, 7, 16, 50, 51]. Studies propose a dosage of 10 mg three to four times daily and it should not be used for longer than 12 weeks [45, 50, 52].

Itopride and clebopride also belong to D2 antagonist’s class, with the second one passing the blood-brain barrier and possible causing extrapyramidal symptoms. Their use in FD is sparse, but few older studies show symptom improvement [11, 53, 54].

Cisapride facilitates the release of acetylcholine in the myenteric plexus via 5-HT4 receptor agonism. There is evidence that cisapride improves FD symptoms, with an NNT as low as 4 [42]. Then again, heterogeneity among trials makes it difficult to reach a conclusion [36, 43]. Worrisome about potentially fatal AE makes this treat-ment not commercially available in several countries [11].

Mosapride, another 5-HT4 receptor agonist, facilitates gastrointestinal motility and gastric emptying, but a 2018 meta-analysis did not show improvement of FD symp-toms when compared to placebo [41, 43]. On the other hand, in a Bayesian network meta-analysis, mosapride was more effective than itopride and acotiamide in treating FD patients [55]. Mosapride has the advantage of no arrhythmia-related AE and recently a once-daily formulation was developed which can improve compliance [41]. A usual regime is 5 mg TID (the extended release 15 mg/daily), between 2 and 6 weeks [16, 41]. Given the current evidence, there is a chance for mosapride to be used in clinical practice, but more data are needed

Prucalopride and Velusetrag are potent high specificity 5-HT4 agonists theoretically leading to less cardiovascular risk. Studies in constipation and gastroparesis are ongoing. Further studies in FD may reveal a potential benefit [7, 16, 36, 56, 57]

Erythromycin, a motilin receptor agonist, has already been shown to improve gastric emptying [58]. Nowadays, its use is almost reserved in gastroparesis, but one study demonstrated its efficacy in bloating [59]. A usual dose between 125 and 500 mg TID for a few weeks may be employed. Tachyphylaxis may develop and decrease treatment efficacy [41, 58].

Trimebutine maleate is also a prokinetic drug with antimicrobial properties [60, 61]. An RCT comparing trimebutine 300 mg BID to placebo for 4 weeks in FD patients showed a statistically significant reduction in FD symptoms [62].

Acotiamide is a selective antagonist of acetylcholinesterase and M1/M2 muscarinic receptors in the presynaptic neuron, improving gastric emptying/accommodation, and appears to act in the gut-brain axis via vasovagal response [36, 63]. Several studies have demonstrated its efficacy in FD and a NNT of 20 was estimated in 2018 [36, 43]. Acotiamide appears to have particular benefit in PDS symptoms [16, 41]. It has a good safety profile and minimal dopaminergic receptor effects [36, 64]. Doses between 50 and 100 mg TID are suitable and improvement in symptoms may occur after 2 weeks [16, 64, 65]. However, acotiamide is not commercially available in Europe. Main prokinetics used in FD are summarized in Table 3.

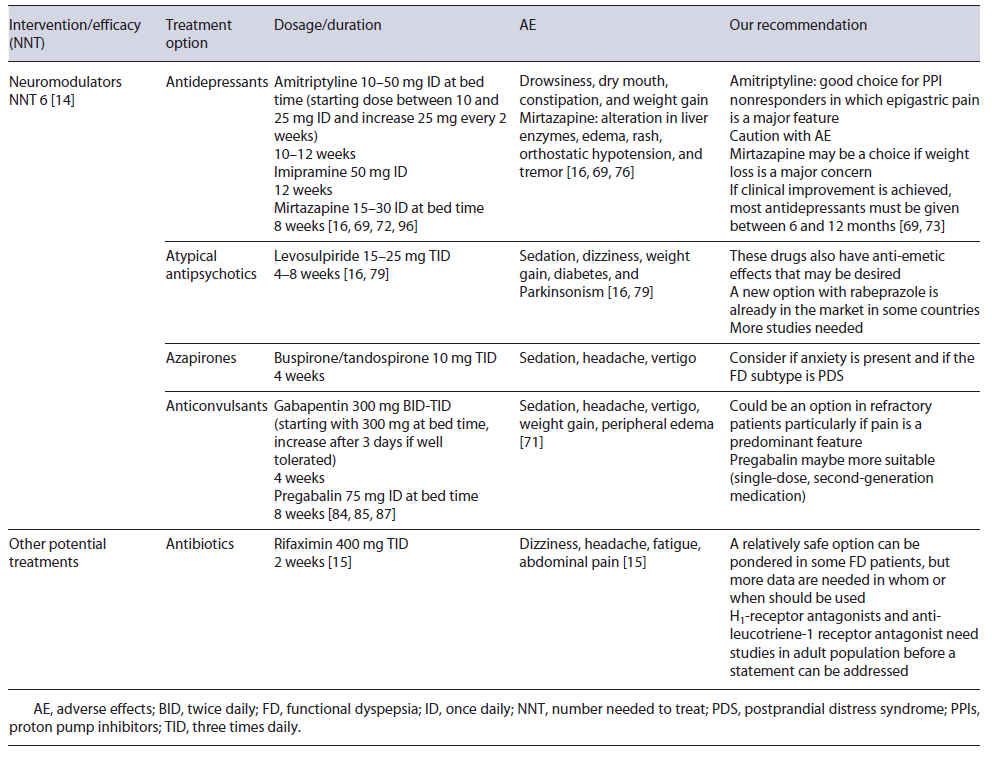

Neuromodulators

Some of the multiple and varied mechanisms involved in FD are related to the gut-brain axis and for this reason it seems logical that targeting this pathway may be beneficial [8, 14, 66, 67]. A significant association between FD with depression and anxiety has already been proved, with the prevalence of depression and anxiety symptoms being 2.5-3 times higher in patients with refractory FD [68].

Neuromodulators seem, for this reason, a strategical treatment for FD. A 2017 systematic review showed the benefit of these drugs, with a NNT of 6, although on sub-group analysis improvement was limited to antipsychotics and tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs). Moreover, when only studies on individuals with no coexistent mood disorder were considered, this benefit was not proven [14]. As suggested by the Rome Foundation, augmentation therapy (combining a second neuromodulator) can also be considered if there is no success of single-agent therapy or if single-agent therapy produces side effects at higher doses [69].

Antidepressants

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are one of the most used drugs for mood disorders, but trials have not shown significant improvement in FD symptoms and a meta-analysis concluded that selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors were not effective in the management of FD [70]. TCAs, such as amitriptyline and imipramine, act on several neuronal pathways [7]. Amitriptyline is one of the most studied antidepressants in FD. Ford et al. [11] in a 2021 meta-analysis showed that amitriptyline was superior than placebo in FD. TCAs appear particularly interesting in EPS or in patients where pain is a major feature [11, 14, 41, 71]. Due to their mechanism of action, TCAs are more prone to cause AE than placebo, but withdrawal due to them was not increased [11]. Drowsiness, dry mouth, constipation, weight gain, sexual dysfunction, arrhythmias, and suicidal intention may be potential AE [16, 69]. Therapeutic dosage of amitriptyline is between 10 and 50 mg daily and periods of 10-12 weeks have been studied in the management of FD [16, 71, 72]. Even so, if clinical improvement is achieved most antidepressants must be given between 6 and 12 months [69, 73]. While more evidence is needed, amitriptyline can be a next first line for FD treatment, especially in EPS, but AE and contraindications must be taken seriously [14, 69].

Imipramine is another TCA studied in FD. An RCT with refractory FD patients showed that imipramine 50mg for 12 weeks was associated with significant symptom relief compared to placebo, but discontinuation due to AE occurred in 18% [74].

Mirtazapine is a tetracyclic antidepressant and it is as-sociated with weight gain [75]. Weight loss, considered an alarm symptom, may be present in up to 40% of tertiary care FD patients [75, 76] and so weight gain may be desirable. An RCT to assess the efficacy of 15 mg of mirtazapine for 8 weeks versus placebo observed that mirtazapine was associated with significant recovery of weight loss and quality of life. A trend was found for im-provement in overall dyspepsia symptoms at week 4 but not at week 8 [75]. Besides this, mirtazapine’s antagonism of the H1 receptor requires further study [19]. Given this evidence, mirtazapine 15-30 mg during 8 weeks may be beneficial to those with FD and weight loss. AE, other than weight gain, may be increased liver enzymes, edema, rash, orthostatic hypotension, and tremor [34, 75].

Venlafaxine is a serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor that exhibits some peripheral gastric effects [7, 16, 77]. However, in an RCT venlafaxine was not more effective than placebo in FD, which may be explained by the lower dosage used (75-150 mg) [7, 77]. In the future, higher doses may be tried, but for now, venlafaxine is not an option in the treatment of FD.

Atypical Antipsychotics

Sulpiride and levosulpiride are atypical antipsychotic agents which block the presynaptic dopaminergic D2 receptors and also have a potential 5-HT4 agonism [69]. Due to this, they are also recognized as an antiemetic drug [78]. In a 2021 meta-analysis, levosulpiride was significantly more effective in treating FD than several other drugs, including some PPIs, prokinetics, and antidepressants, despite uncertainty around the results (small number of trials and patients) [79]. Levosulpiride dosage is 15-25 mg TID for a short period [41, 78]. AE may include sedation, dizziness, weight gain, diabetes, and Parkinsonism-like symptoms [41, 69].

Azapirones

Buspirone and tandospirone (azapirones) were developed as anxiolytics drugs [7, 69]. Peripherally, they promote relaxation of the proximal stomach, improving gastric accommodation [7, 16, 80]. In 2012, a study with 17 FD patients showed that buspirone significantly reduced the overall symptom severity compared to placebo [81]. Also, a study of tandospirone showed an improvement in upper abdominal pain and discomfort versus placebo [82]. Despite this, in meta-analysis, azapirones were unsuccessful in providing improvement in FD patients [14]. This negative result can be at least somewhat explained by the small number of trials and patients included [14]. Possible AE are sedation, headache, and vertigo. A dose of 30 mg daily in divided doses (TID) for 4 weeks has been used [7, 16, 34, 81, 82].

Anticonvulsants

Some anticonvulsants (e.g., gabapentin and pregabalin) are employed nowadays in controlling neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia [69, 83]. Reducing neurotransmis-sion in overly active pain circuitry is likely the underlying mechanism behind their efficacy [69, 83, 84]. Gabapentin and pregabalin reduce excessive release of excitatory neurotransmitters such as glutamate and both have been recently studied in FD [69].

Gabapentin led to a significant improvement of dyspeptic symptoms such as abdominal pain and postprandial fullness in a retrospective study [85]. An RCT on 126 refractory FD patients, either taking omeprazole 20 mg ID plus placebo or omeprazole 20 mg ID plus gabapentin 300 mg BID, showed that both groups had a reduction in the severity of symptoms that was higher in the gabapentin group, although without statistical significance [86]. The studied treatment duration in gabapentin was 4 weeks and a dosage up to 900 mg daily (300 mg TID) may be used. Treatment should begin with a small dose, such as 300 mg at bed time, and increased after 3 days if tolerated [85, 86]. Main AE of these drugs are sedation, headache, vertigo, weight gain, and peripheral edema [69].

Pregabalin, a second-generation drug, appears to have a better profile in potency, pharmacokinetics, and less AE compared to gabapentin [69, 83, 86]. An RCT of 72 enrolled patients with FD, including PPI nonresponders, showed that pregabalin for 8 weeks led to significant im-provement of dyspeptic symptoms compared to placebo, especially in patients with epigastric pain. No serious AE were reported [83]. The duration period was 8 weeks, with a dosage of 75 mg daily. Though this class may become a valid strategy particularly in those whom pain is a predominant feature, additional evidence is needed.

New Targets: Immune Response and Dysbiosis

New data about altered local immune response, main-ly in duodenum, make it attractive to new treatment targets [12, 36]. Steroids are one of the most commonly used immunosuppressive drugs. Budesonide has a good pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profile, and it is safely used in several gastrointestinal diseases which makes it appealing in FD [87-89]. Even so, most of the formulations available do not deliver budesonide in the upper gastrointestinal system [88].

Talley et al. [89] tried a budesonide 9 mg/day liquid form versus placebo in an RCT with 162 patients with FD for 8 weeks. There was no significant change in eosinophil count from baseline to post-treatment in either group, but a drop in duodenal eosinophil count was significantly correlated with a decrease in postprandial fullness severity and frequency as well as early satiety severity. These results show a lack of efficacy of this formulation but validate the theory that a decrease in duodenal eosinophil counts may be associated with FD symptom improvement [89].

Histamine and mast cell infiltration have likewise been linked with FD. For this reason, anti-allergic therapies may seem a good option for new studies. Antagonism of H1 receptor was studied in visceral hypersensitivity in irritable bowel syndrome and appears to be effective in children with FD [12, 90]. A combination of histamine-1 and histamine-2 receptor blockade was reported in a case series in Australia. Fourteen patients with FD received ranitidine 150-300 mg BID and loratadine 10-20 mg ID during 1-24 months (median 4 months). Treatment resulted in symptom improvement in 10 patients, and those who responded had significantly higher baseline duodenal eosinophil counts versus nonresponders [18].

Montelukast, an anti-leucotriene-1 receptor antagonist, was studied in children with FD, with a statistically significant symptom improvement [91]. On the other hand, RCTs to access the response to these drugs in the adult population are lacking. These drugs are generally well tolerated, with few AE, and may have potential to ameliorate FD symptoms [12].

The alteration in gut microbiota has been studied in both functional and inflammatory GI disorders [12]. Gastrointestinal infection can induce FD and an interest in modulating gut microbiota has emerged [92].

Rifaximin is a poorly absorbed oral antibiotic with a good safety profile. In FD, an RCT including 86 individuals examined the efficacy of 2 weeks 400 mg of rifaximin TID versus placebo. Patients were observed at week 2 (end of the treatment), 4, and 8. At week 8, a significantly difference was observed in symptom relief in the rifaximin’s group. The effect was more pronounced in women and a similar incidence of AE was reported [15].

More RCTs are mandatory before a definitive role for immune and microbiota modulation in FD’s treatment becomes a reality. Table 4 summarizes treatment options for FD regarding neuromodulators and new therapies.

Other Therapies

Bismuth salts can suppress H. pylori and so its use in eradication treatment. Role for bismuth salts in FD can also be present since it inhibits peptic activity. Even so, beneficial effect with bismuth salts in FD in older studies is difficult to validate nowadays, without newer studies not including H. pylori-infected patients [20, 93].

Simethicone is a defoaming agent. Older studies show overall improvement in FD with similar results to those achieved with cisapride and with faster relief. A clinical plausibility due to decrease in abdominal gas makes it appealing in those patients where bloating is a major complain. A dosage between 84 and 105 mg TID during 8 weeks has been used. AE are infrequent but nausea, diarrhea, and constipation may occur [94, 95].

Clinical Management: More Than a Disorder, a Patient!

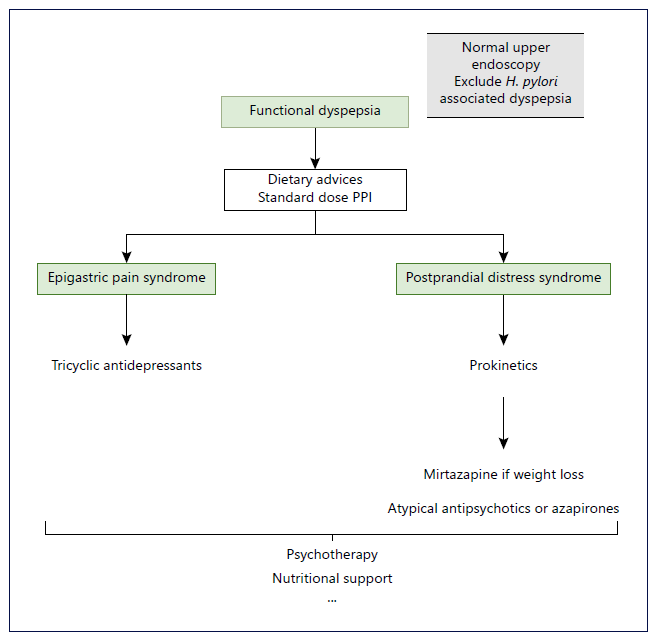

As we all know, FD is a complex and heterogeneous en-tity. The most important step in treating these patients is to manage expectations. One treatment may not work and there may be a need to proceed to others. Clinical evaluation should be done between 4 and 12 weeks after a new therapy has been started. If failed, choosing the next target should take into account the patient’s predominant complaints and previous comorbidities. Attention to contraindications of some of these therapies must be present and it is advisable to explain the potential AE of the new treatment. Figure 1 represents a schematic algorithm proposed for the management of FD.

Although treating FD is a hard task, do not give up! A tailored approach is probably the best option so far.

Fig. 1 Schematic representation of a pro-posed algorithm for the management of functional dyspepsia. H. pylori, Helicobacter pylori; PPIs, proton pump inhibitors. *Dietary advices may be eating slowly at regular intervals, decrease the lipid sup-ply and reducing consumption of coffee-and carbonated drinks. **Standard dose PPI may include esomeprazole 20 mg, pantoprazole 40 mg; rabeprazole 20 mg and lansoprazole 30 mg.

Conclusion

FD is a multifactorial disorder, with recent discoveries in some of the pathways involved, including the role of the immune system. Current treatment options are not ideal in terms of efficacy, but also regarding AE. Likewise, targeting the pathophysiology of FD still needs to be refined.

Future studies should focus on accurately defining FD, according to Rome IV criteria, and on analyzing FD sub-division according to predominant symptoms. Standardization of dose and duration of treatment is also a point to look for. Trials with new medications are missing and some of the old drugs should be revisited. Furthermore, management of symptom relapse after successful treatment is still a matter of doubt: should we use the same drug or try a different option? This is another question for future studies to answer. For now, treatment of FD remains an old story revisited, but a new story to be told is not so far away.