Introduction

Since its emergence in December 2019, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has spread into a global pandemic of a disease known as COVID-19, with significant public health implications around the globe [1].

The SARS-CoV-2, an enveloped RNA virus, is predominantly transmitted via respiratory droplets [2]. After contact with the virus, it enters the human cells via the angiotensinconverting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor using its spike protein S1 subunit. While primarily expressed in the lungs, the ACE2 receptor is also expressed in many extrapulmonary tissues, including the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. High levels of ACE2 receptors were found on the luminal surface of differentiated epithelial cells in the terminal ileum and colon [2-4].

Acute COVID-19 infections in pediatric patients have been milder in severity, with quicker recovery and fewer sequelae compared to adult infection [4, 5]. This difference is believed to be due to multiple factors such as variations in the distribution of ACE2 receptors, T-cell and B-cell responses, and the balance of modulating and pro-inflammatory cytokines [2].

Concerning the pediatric population, as of April 2021, the estimated incidence of COVID-19 in Portugal was almost 15% of all cases [6]. Yet, according to the Surveillance Epidemiology of Coronavirus Under Research Exclusion for Inflammatory Bowel Disease (SECURE-IBD), only 103 cases were reported [7].

Until the moment, the knowledge concerning the risk of COVID-19 in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients, particularly pediatric IBD patients, is still scarce [8, 9]. Recent studies seem to show that IBD patients are at no greater risk than the general population [9].

This report aims to review the experience of our center and describe the disease course of COVID-19 in our sample of pediatric IBD patients.

Materials and Methods

This retrospective study included all patients under 25 years with IBD infected by SARS-CoV-2 between December 2019 and April 2021 and followed by the Unit of Pediatric Gastroenterology in Centro Hospitalar São João anytime during that period.

Telephone inquiries were performed, in addition to consultation of medical records, and the following variables were collected: demographic data (age, gender), clinical data at the time of COVID-19 (type of IBD, IBD extension according to Paris classification, medication for IBD, disease activity according to the PUCAI and PCDAI scores measured in the last visit previous to infection as well as fecal calprotectin measured within the same timeframe, and presence of comorbidities and COVID-19 data [vaccination status, severity and length of symptoms, presence of GI symptoms, whether medication for IBD was stopped during infection, complications, and need for hospitalization]). COVID-19 severity was determined as stated in the World Health Organization (WHO) definition, being mild when symptoms were present with no evidence of viral pneumonia or hypoxia and moderate when there were clinical signs of non-severe pneumonia [10].

A descriptive analysis was performed. Continuous variables with asymmetrical distribution were presented as a median (minimum-maximum).

The study was approved by the ethical committee of our insti-tution. All information is anonymous and confidential.

Results

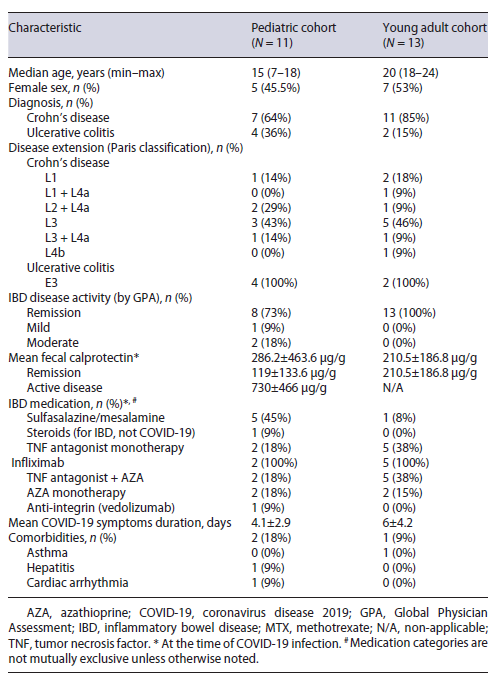

Of the 338 patients with IBD included, only 268 were available to answer the telephone inquiry. Of these, 24 participants had COVID-19 (Table 1). Overall, the mean age was 19 years old (minimum seven and maximum 24 years old). Specifically, there were 11 (45%) pediatric patients under 18 years old (mean 15 years) and 13 (55%) young adults (mean 20 years). Both groups had an equal gender distribution (male-to-female ratio of 1:1).

Table 1 Demographics, disease characteristics, and clinical outcomes of pediatric and young adult IBD patients with COVID-19 infection

Concerning the IBD classification, 75% (n = 18) had Crohn’s disease, whereas only 25% (n = 6) had ulcerative colitis. Among patients with Crohn’s disease, four had ileal disease, three had colonic disease, ten had ileocolonic disease, of which two had concomitant involvement of the distal esophagus, and one patient had exclusive upper disease distal to the ligament of Treitz. All patients with ulcerative colitis had extensive disease according to the Paris classification.

Most patients were in clinical remission (n = 21) with only one case of mild disease activity and two cases of moderate disease activity. All three patients with active disease had ileocolic Crohn’s disease and a mean disease duration of almost 6 years at the time of COVID-19. Fecal calprotectin had a mean value of 730 ± 493 μg/g in the group of patients with active disease and of 158 ± 213 μg/g in the remission group.

The majority of patients were under treatment with a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) antagonist (58%, n = 14), most commonly infliximab. Of these, 50% were treated with anti-TNF monotherapy and the other 50% with an association of anti-TNF with azathioprine.

Most patients had no comorbidities other than IBD (83%).

Regarding the COVID-19 disease, 17% (n = 4) were asymptomatic, and the remaining patients had mild disease. Average symptom duration was 4 days. In one case, a 19-year-old patient, COVID-19 infection occurred after the first dose of vaccination against COVID-19 (the vaccine used is unknown). There were no reported gastrointestinal complaints. There were no reports of complications or hospitalizations due to COVID-19, and most patients (90%) did not require interruption of their IBD treatment. The three patients who did interrupt their treatment did so for mandatory quarantine, which prevented them from going to the hospital to receive their intravenous treatment.

Discussion/Conclusion

We analyzed a total of 24 patients with IBD, less than 25 years of age, infected with SARS-CoV-2.

Despite being commonly referred to as a respiratory illness, it is now clear that COVID-19 can also affect the GI system, particularly in the pediatric population, as evidenced by a prevalence of 6% of GI symptoms found in a metanalysis of 1,810 healthy pediatric patients [11]. In our study, however, no GI symptoms were observed. This might be explained by the median age in our sample, which was higher than the median age in the metanalysis by Badal et al., even when adjusted to include only the pediatric patients (15 years [7-18] compared to 8 years [6-10]).

We reported no hospitalizations and no complications from COVID-19. These findings are in line with other studies, such as the SECURE-IBD registry that found a rate of 7% hospitalization, a 2% ventilation support requirement, and no deaths in a pool of 209 COVID-19 cases with pediatric IBD [4]. In addition, an observational study of 522 IBD patients, including 59 children in an Italian tertiary referral center, reported no admissions for SARS-CoV-2 infection [12]. Our findings are also identical to reports on young adults who are generally described to have a milder disease with a good prognosis and low hospitalization rates [3]. In fact, our sample results showed a significant overlap between both age groups, which can be explained by the high mean age found in the pediatric group.

The reasons why IBD patients appear to be less affected and develop milder clinical pictures are still unknown. It has been suggested that the lower infection rate may be a consequence of improved adherence to shielding recommendations [13]. Among the possible risk factors for severe COVID-19 described in the literature are IBD treatments such as steroids and thiopurines, whereas the use of TNF-antagonists was reported as protective [4, 14, 15]. Of note, despite concerns shown by the patients and their parents of a higher risk of infection in patients under biologic treatment, it appears that the blockage of the cytokine storm by immunomodulators taken for IBD, which lead to the control of bowel inflammation, may assist in the prevention of COVID-19 severe symptoms [5, 16]. In fact, a study conducted during the first pandemic wave found that up to 23% of pediatric patients who delayed or temporarily discontinued their biologic therapy due to the lockdown experienced a disease exacerbation [17]. Moreover, Turner et al. showed that pediatric patients who interrupted their IBD treatment had a significant rate of developing flairs while those who continued treatment had no complications [18].

The cumulative experience of the last 2 years is in favor of continuing ongoing IBD therapy and not delaying the beginning of conventional immunomodulators or biological therapy because of the pandemic situation, in patients without COVID-19 [19, 20].

An open question is the need for treatment interruption in patients with COVID-19.

The ECCO-COVID Task Force and the IOIBD recommend the interruption of anti-TNF, thiopurines, and corticosteroids in patients with SARS-CoV-2, regardless of symptoms [15, 21, 22].

In our sample, three patients had to delay their intravenous treatment during COVID-19 infection due to mandatory quarantine. The expected half-life of anti-TNF such as infliximab is almost 10 days, but its effect is largely potentiated by the use of thiopurines like azathioprine whose immunosuppressive effect goes beyond their half-life. Perhaps, while more evidence is awaited, a personalized approach should be considered according to severity and clinical course of the disease.

Additional risk factors found for hospitalization in pediatric IBD patients with COVID-19 included other comorbidities besides IBD, moderate or severe IBD disease activity, and presence of gastrointestinal symptoms [4]. In our sample, comorbidities were found in a rather small number of cases, and only two patients had moderate disease activity. Regardless, no complications nor hospitalizations were reported in this group.

This study has limitations. First, its retrospective nature might have led to the underestimation of the severity and length of the symptoms by the participants. Secondly, no statistical analysis was performed due to the sample size.

In conclusion, we present the reassuring experience of our center in the follow-up of pediatric and young adult patients with IBD who developed COVID-19. Our data suggest that pediatric IBD patients have a low risk for complications and hospitalization, regardless of the IBD treatment. A larger multicentric study with longer follow-up would be required to draw more conclusions, but we believe that this report is encouraging and allows for safe counseling regarding treatment options and school attendance in pediatric and young adult IBD patients.