Introduction

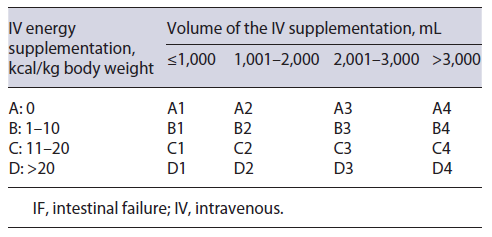

According to the European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN), intestinal failure (IF) is defined as the reduction in gut function below the minimum necessary for the absorption of macronutrients and/or water and electrolytes, such that intravenous supplementation (IVS) is required to maintain health and/or growth [1]. IF can be classified according to functional, pathophysiological, and clinical features. From a functional perspective, IF can be classified into three types. In type I, short-term IF, IVS is usually required over a period of days to a few weeks. Type II is a long-term, subacute condition, where IVS is maintained for weeks/months, and type III is a chronic condition, with metabolically stable patients requiring IVS over years, sometimes during all their lives [1, 2]. Regarding pathophysiological classification, there are five major pathophysiological mechanisms for IF: short bowel, intestinal fistula, extensive small bowel mucosal disease, intestinal dysmotility, and mechanical obstruction. From a clinical perspective, classification is based on the weekly IVS energy and volume requirement. It can be categorized from A to D regarding the IVS energy supplied weekly, and from 1 to 4 for the volume of the IVS [1]. The clinical classification is illustrated in Table 1.

IF treatment aims to restore bowel function through nutrition, pharmacological, and/or surgical therapy [3]. In long-term IF, mainly in type III, although some oral nutrient intake is possible in most individuals, home parenteral nutrition (HPN) and/or home parenteral hydration (HPH) remain the foundation of treatment. This comprises the administration of macro- and micronutrients, fluids, and electrolytes via a central venous catheter at the patients’ home [4]. Long-term IF patients require a multidisciplinary approach since treatment is complex and requires differentiated expertise.

Although type I IF is very common in surgical wards, type III chronic IF is rare and is, usually, considered the rarest of chronic organ failures [5, 6], and type II is even less frequent. Due to the rarity of long-term IF, comprehensive studies are scarce. To the best of our knowledge, there is minimal literature on the effect of HPN/HPH on nutritional status and survival in patients with IF. The authors here outline their experience of the use of HPN/HPH, amounting to 10 years of experience. The aim of this study was to assess the impact of HPN/HPH on nutritional status and survival of long-term IF patients, as well as HPN/HPH-related complications.

Materials and Methods

The authors performed a retrospective analysis of patients with IF who underwent, or were currently under HPN and/or HPH, followed in a single large tertiary Portuguese hospital. IF outpatients were managed in our hospital’s Artificial Nutrition Outpatient Clinic, by a multidisciplinary nutrition support team (NST) including physicians (gastroenterologists and surgeons), a dietitian, and a nurse. After the outpatient appointment, the nutritional decisions were discussed with the team pharmacists and, whenever needed, with other physicians. The criteria for acceptance into the HPN/HPH program included the inability to maintain a normal nutritional status with oral/enteral support after hospital discharge, due to IF from underlying disease, as well as patient commitment to ensure compliance with treatment and adequate hospital follow-up. Some patients presented the competence and skills to achieve autonomy for self-administration of parenteral nutrition. For those patients where self-administration or administration by a relative or caregiver is impossible, the hospital nurses from home care provided daily home support.

Before entering the HPN/HPH program, all subjects and/or their legal caregivers were carefully informed in detail about the risks and benefits of this therapy and gave their informed consent. The present study is retrospective and the only initial exclusion criteria was an incomplete clinical file.

The following clinical data were collected for each patient: age, gender, underlying condition motivating IF, IF classifications (functional, pathophysiological, and clinical classification), anatomical characteristics, duration and characteristics of parenteral support during most of the HPN/HPH period (after initial stabilization and before the final withdrawal period before finishing parenteral support), body mass index (BMI) at the beginning and at the end of follow-up, HPN/HPH-related complications requiring hospitalization, and current patient status (deceased, alive with HPN/HPH, or alive without HPN/HPH). For the deceased patients, the date of death was recorded, and survival was calculated in months after the beginning of HPN/HPH. For the remaining patients, survival was calculated in months from the beginning of follow-up until August 2021. The cause of death was also assessed (HPN/HPH related, comorbidity related, or due to acute infection, other than catheter related).

Statistical analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (IBM SPSS® Statistics, version 25.0). Categorical variables are presented as frequencies and percentages, and continuous variables as means and standard deviations. Normal distribution was checked using the Shapiro-Wilk test or skewness and kurtosis. A parametric independent t-test was used to compare variables normally distributed. All reported p values are two-tailed, with a p value below 0.05 indicating statistical significance.

Results

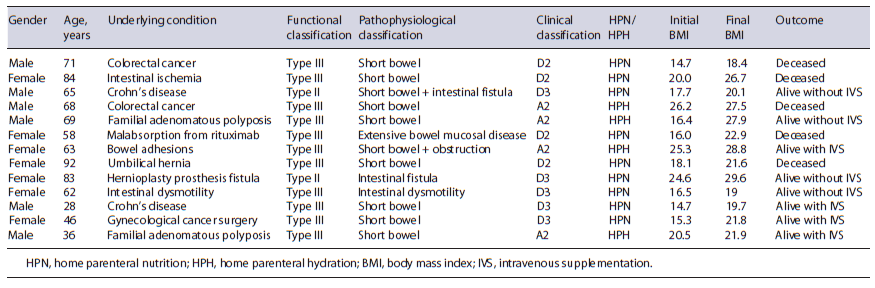

From the total HPN/HPH patients, 3 were excluded due to incomplete clinical files. A total of 13 adult patients with IF under HPN/HPH were included: 7 females (53.9%) and 6 males (46.1%), aged between 28 and 92 years (mean 63.46 ± 18.433 years), with a follow-up period ranging from 6 to 114 months (mean 28.8±29.207 months). The majority of patients (n = 11, 84.6%) presented type III IF, while the remaining 2 patients presented type II IF (15.4%), both with long-term type II IF, allowing sufficient metabolic stability to continue treatment at home with HPN. Most patients (n = 10, 76.9%) presented IF due to short bowel syndrome (SBS) of several causes: abdominal cancer surgery (n = 3), Crohn’s disease (n = 2), familial adenomatous polyposis (n = 2), intestinal ischemia (n = 1), multiple bowel adhesions (n = 1), and incarcerated umbilical hernia (n = 1). Of the SBS patients: 6 presented terminal ileostomies, 3 presented terminal jejunostomies (all 3 with less than 100 cm of small bowel), and 1 patient presented ileostomy plus colostomy. In all patients, a subcutaneously tunneled central catheter (Hickman catheter) was placed. Nine patients (69.2%) were receiving HPN, and 4 patients (30.8%) were under HPH. No patient received glucagon-like peptide 2 (GLP-2) analogues. At the beginning of HPN/HPH, 8 patients (61.5%) were underweight (BMI <18.5) and 5 patients presented a normal BMI. The characteristics of the study population are described in Table 2.

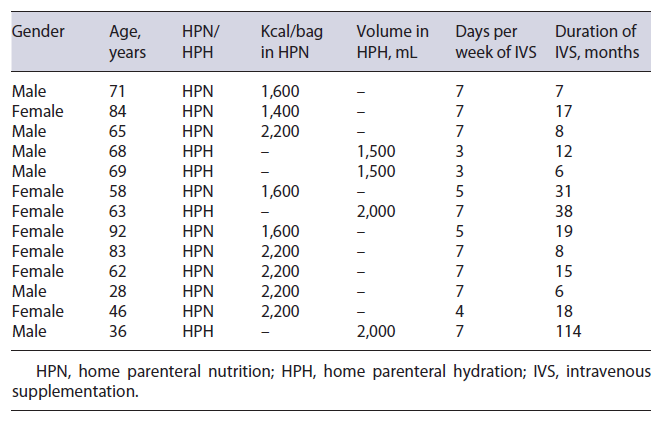

The mean duration of HPN/HPH was 23 months. HPN was administered for a mean period of 6.2 days/week and HPH for a mean of 4.6 days/week. Table 3 summarizes HPH/HPH support characteristics and duration for each patient. All patients improved their BMI during the follow-up period (mean BMI at the beginning of follow-up 18.9 vs. 23.5 at the end, p < 0.001). Regarding clinical outcome at the end of follow-up, 4 patients (30.8%) were alive without IVS, 4 patients (30.8%) maintained IVS, and the other 5 patients (38.4%) died (Table 2).

Four patients were able to discontinue home parenteral support (2 presented type II IF and 2 type III IF). The 2 patients with type II IF could be treated and resumed oral feeding: one had severe Crohn’s disease and required multiple surgical interventions, namely ileostomy, resulting in SBS, and required HPN for 8 months, but after reconstruction and medical therapy optimization he was able to resume exclusive oral intake; the other type II patient presented IF due to a jejunal fistula that resulted from a hernioplasty surgical complication and required 8 months of HPN. Once the fistula was surgically corrected, the patient resumed oral intake. Also, 2 type III IF patients resumed oral feeding: one underwent total proctocolectomy with terminal ileostomy due to familial adenomatous polyposis, and required 6 months of HPH until ileostomy output was stabilized. The fourth patient presented IF due to intestinal dysmotility and required 15 months of HPN. Afterwards, this fourth patient was able to maintain an adequate nutritional status with oral in-take plus enteral supplementation. The 4 other non-deceased patients who maintained home parenteral support all presented type III IF.

Eight patients (61.5%) were hospitalized due to catheter-related complications, 3 of them with more than one hospital admission (mean hospitalization episodes of 2.25 per patient, with a mean hospital stay of 24.5 days, minimum 3 days and maximum 143 days). From the total of 18 hospitalizations, catheter-related blood stream infections (CRBSI) accounted for the majority of hospital admissions (66.7%, n = 12). Other catheter-related complications included catheter exteriorization/dysfunction (22.2%, n = 4) and venous thrombosis (11.1%, n = 2). Regarding the causes of death for the deceased patients: 3 patients died with acute infection (other than CRBSI), and 2 patients died from comorbidities. There were no deaths related to HPN/HPH.

Discussion

The present study included adult patients with IF from multiple etiologies, referred to a single center with a multidisciplinary NST, dedicated to IF patients and capable of providing specialized care to this complex condition. IF may occur due to acquired or congenital, gastrointestinal or systemic, benign or malignant diseases [7]. It may be a self-limiting short-term disorder (type I IF), or may become a long-lasting, chronic condition (type II or type III IF). According to a previous European cross-sectional study, SBS was the main cause of long-term IF, accounting for 74.7% of HPN indication in adults [8]. SBS is a rare disease that results from extensive intestinal resection, leading to a residual small bowel length of less than 200 cm, which translates into loss of absorptive intestinal surface. HPN/HPH represents the standard-of-care and life-sustaining therapy in long-term IF patients [4]. Although IF may be reversible in SBS patients through intestinal adaptation and rehabilitation programs, HPN weaning off is more likely to occur in patients with partial or total colon in continuity, and less likely in patients with less than 100 cm of small bowel length [9].

Our study population presented a heterogeneity of underlying diseases motivating IF, with SBS being the major cause. However, even patients within the same patho-physiological IF class suffered from several underlying disorders and formed a very heterogeneous group. In the present study, we did not include any patient with type I IF, which is the classic situation occurring after abdominal surgery, with IVS usually being required over a period of days to a few weeks and normally administrated during a hospital stay. Most patients in our study presented type III IF, a chronic condition in which patients are metabolically stable, and usually require long-term IVS over years. In the study population, all non-deceased patients who maintained home parenteral support at the end of follow-up presented type III IF. Of the 4 patients who were able to discontinue home parenteral support, two presented type II IF and two type III IF. Type II IF is a long-term subacute condition where IVS is maintained for weeks/months. Typically, these are metabolically unstable patients, frequently with multiple digestive fistula, needing an interdisciplinary intervention. They may need hospital care for several weeks but may also be home treated for several months with HPN, in order to become fit enough for reconstructive surgery. The 2 patients with type II IF who resumed oral feeding presented a clinical condition that could be surgically reverted after a few months of home parenteral support, reinforcing the role of reconstructive surgery in weaning off parenteral sup-port. Regarding the two type III IF patients alive without home parenteral support, one required months of HPH after terminal ileostomy, until fistula output was stabilized, and the other required over a year of HPN due to intestinal dysmotility, but was finally able to maintain an adequate nutritional status with oral intake plus enteral supplementation. Besides reconstructive surgery, intestinal adaptation plays an important part in weaning off parenteral support. Intestinal adaptation is the natural compensatory process that occurs after massive intestinal resection and sometimes nutritional autonomy may be achieved. Adaptation is a complex process that responds to nutrient and non-nutrient stimuli [10, 11]. Stimulating the remaining bowel with enteral nutrition enhances this process. GLP-2 is an enteroendocrine peptide, released in response to luminal nutrients, responsible for initiating and maintaining small bowel adaptive responses after resection, thus improving nutrient absorption [12-14]. Teduglutide is a long-acting GLP-2 analogue, and has been approved for SBS patients as a long-term aid to parenteral nutrition weaning [15, 16]. Teduglutide’s use is usually reserved for SBS patients who are unable to be weaned from parenteral nutrition despite aggressive use of the more conventional measures, particularly in those SBS patients who have developed significant complications or describe severe impairment in quality of life related to parenteral nutrition use. Gastrointestinal neoplasia constitutes a contraindication for Teduglutide’s use, which some of our patients present. Also, the cost for this medication is significantly high and its accessibility is limited. In our center, no patient has yet received treatment with any GLP-2 analogue.

To the best of our knowledge, there are limited data on the effect of HPN on long-term IF patients’ nutritional status. In a small retrospective study of 12 patients with systemic sclerosis, HPN significantly improved nutrition status [17]. In our study, home parenteral support was associated with a significant increase in BMI in all patients with IF.

For long-term IF patients with benign disease, long-term survival under HPN/HPH can reach 80% at 5 years [9]. However, treatment-related morbidity and mortality are dependent on adequate patient management and follow-up by a multidisciplinary NST [2, 9]. A systematic review that aimed to assess the role of NSTs in the over-sight of parenteral nutrition administration in hospitalized patients demonstrated a decreased incidence of inappropriate parenteral nutrition use in centers with NST compared to centers with no such multidisciplinary team [18], thus suggesting the benefit of an NST in managing patients under parenteral nutrition. The main long-term HPN complications are catheter related, in particular CRBSI, which can be responsible for up to 70% of hospitalizations [4]. Treatment-related complications are reported to account for around 14% of deaths in patients with long-term IF [19]. Preventing CRBSI relies on patient/caregiver education on adequate hand washing and disinfection policy, correct catheter manipulation, and regular change of intravenous administration sets [2, 4]. As for catheter-related venous thrombosis, we do not routinely use pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis for primary prevention, in accordance with the guidelines [2]. Despite optimal conditions of catheter placement, and extensive education of caregivers on catheter handling, we observed that infections and mechanical complications are still common in IF patients under HPN/HPH. Catheter-related complications, mainly CRBSI, were responsible for two thirds of hospitalization episodes, which is in accordance with the available literature [2, 4, 20]. In a large study of patients under HPN, 15% of reported deaths were due to HPN-related complications, namely central line infections and associated liver disease [21]. In the present study there were no deaths directly related with HPN/HPH, which may result from the existence of an experienced multidisciplinary NST responsible for managing these patients.

This study presented some limitations. It was carried out in a single hospital, data collection was dependent on each patient’s clinical files, and the study population was small, in relation to the rarity of this clinical entity. Also, long-term complications from HPN such as cholestasis, liver disease, and osteoporosis were not accessed. Nevertheless, the present study suggests that, even in a health system where there is no tradition of long-term management of IF patients and with only a few teams with some experience, home parenteral support can be a safe and effective therapy.

In conclusion, home parenteral support remains the gold-standard and life-sustaining therapy of long-term IF due to any underlying condition. In this study, HPN significantly improved IF patients’ BMI. Although HPN/HPH-related hospitalizations were common due to CRB-SI, no deaths were attributed to the parenteral support, thus suggesting that HPN/HPH is an adequate and safe therapy for IF patients, especially if patients benefit from an experienced nutrition team.