Introduction

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a lifelong disease characterized by chronic and continuous inflammation of the colon and rectum. Acute severe ulcerative colitis (ASUC) is a particular disease setting in inflammatory bowel disease [1] and is diagnosed according to the Truelove and Witts [2] criteria, combining signs of clinical disease severity and systemic toxicity. Despite the recent advances in inflammatory bowel disease management, it still constitutes a clinical and therapeutic challenge, with a 10-20%risk of early colectomy [3-5].

Corticosteroid therapy is the mainstay of ASUC treatment, which is successful in around two-thirds of patients. In steroid-refractory patients, infliximab (IFX) is well established as a second-line treatment in ASUC management [1, 6, 7].

Several pathophysiologic characteristics, namely, high inflammatory burden, low albumin levels, and increased IFX clearance, suggest that higher IFX dosages would be required in this context [8, 9]. Thus, intensification regimens with higher induction doses or shorter intervals have been proposed and attempted in order to increase therapeutic success [10]. Their role, however, is not clearly established due to controversial findings and lack of well-designed randomized control trials. Nevertheless, the most recent British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines recommend accelerated regimens in patients who fail to respond to IFX standard dose after 3-5 days [6]. We present 3 cases of ASUC treated with IFX intensified/accelerated regimens and discuss the evidence for and against this strategy.

Case Presentation

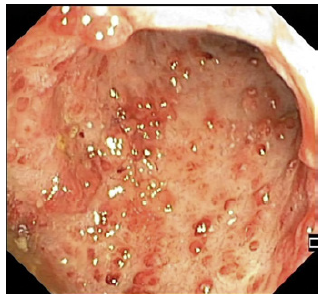

First, we present the case of an 18-year-old female with past medical history of asthma under inhaled corticosteroids. She presented in the emergency department with bloody diarrhea (>6 bowel movements/day), associated with 12% bodyweight loss, severe abdominal pain, and vomiting for 3 weeks. On physical examination, she was feverish (38.5°C), with increased heart rate (108 bpm) and diffuse abdominal tenderness with no signs of peritonitis. From blood analysis, severity signs were present, from which microcytic anemia (hemoglobin 11.9 g/dL), hypoalbuminemia (3.0 g/dL), and high C-reactive protein (CRP; 224 mg/dL) stood out. Hematological involvement with severe coagulopathy was also identified (INR 4.1). Proctosigmoidoscopy revealed the presence of deep ulcers throughout the visualized length (shown in Fig. 1a) compatible with severe UC, which biopsies confirmed. The patient underwent an abdominal computed tomography (shown in Fig. 1b) which revealed toxic megacolon and was then hospitalized under intravenous corticosteroids (1 mg/kg/day), after surgical team consultation.

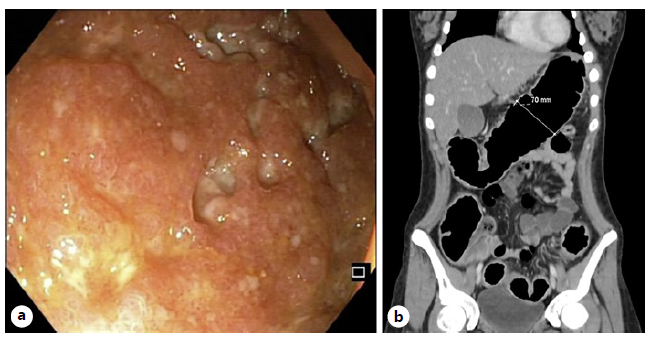

Fig. 1 a Proctosigmoidoscopy showing deep mucosal ulceration in the sigmoid (case 1). b Abdomen CT revealing trans-verse colon dilation, consistent with toxic megacolon (case 1).

At day 3 and 5, she showed only mild clinical response and our decision was to start IFX on a 10 mg/kg dosage. After first infusion, she had a good clinical response; however, this improvement only lasted for 3 days. Decision was agreed toward an accelerated induction regimen with this high-dose strategy and a new infusion was administered 5 days after the first. The temporary clinical improvement scenario repeated itself and the third infusion was taken after 6 days, completing the induction phase in just 11 days. IFX blood levels measured 3 days after drug induction conclusion were high (>20 μg/mL). This time and still under i.v. corticosteroids as adjuvant therapy, the clinical response got lasting and progressive, also with radiological normalization of colon diameter and metabolic correction of biomarker alterations and deficits, such as in iron and vitamin K. She was discharged with a 6/6 weeks IFX plan under proactive therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM), corticosteroid tapering, and plan to start combined therapy with immuno-suppression on the short term. No drug-related events were recorded and 1 year after the hospitalization patient remains in remission with this strategy.

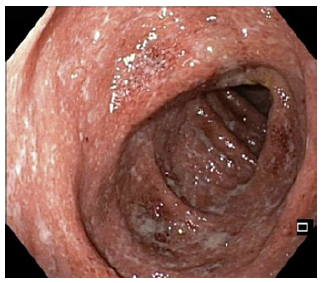

In second place, we present the case of a 26-year-old male diagnosed with left-sided UC for 2 years, under oral and topical mesalazine. He presented clinical deterioration for 3 months before being hospitalized. Workup revealed elevated CRP (83 mg/dL), hypoalbuminemia (1.9 g/dL), severe anemia (hemoglobin 8.3 g/dL), and an endoscopic Mayo score of 3 in the left colon (shown in Fig. 2). After partial clinical response to i.v. corticosteroids, symptomatic worsening was observed on day 4, when tapering was started, and IFX was initiated on the standard dose (5 mg/kg). He then maintained good clinical improvement and was discharged with corticosteroid tapering plan and a new scheduled IFX infusion in 2 weeks.

Two weeks after the second dose, he presented with an ASUC episode back in our institution and was hospitalized with i.v. corticosteroid resume and a new IFX infusion, this time at 10 mg/kg, when TDM revealed unmeasurable trough levels and no antibodies. During hospitalization, by reason of severe weight loss and poor nutritional status, partial parenteral nutrition was initially used and progressively withdrawn until the time patient was discharged, when clinically stable, with IFX 10 mg/kg regimen every 4 weeks. Treatment with azathioprine was included on the last days of hospitalization and the patient remains now, 2 years after this episode, on remission under combined therapy, with IFX standard dosage, after tapering driven by TDM.

Finally, the third case is a 78-year-old male, previously followed for an ulcerative proctitis for 12 years, under oral mesalazine, as he refused long-term topical therapy. He came to the emergency department due to new onset of bloody diarrhea (>20 episodes/day) and tenesmus for 1 month. At clinical examination, he presented with severe dehydration (blood pressure of 94/52 mm Hg and heart rate of 150 bpm). Blood analysis revealed high CRP (18 mg/dL), hypoalbuminemia (2.6 g/dL), and hyperlactacidemia (4.7 mmol/L). He underwent a colonoscopy that revealed an extensive UC with diffuse deep ulcerations (Mayo score 3, shown in Fig. 3), mainly in the sigmoid and rectum. He started high-dose i.v. corticosteroids with no satisfactory response at day 3 and day 5. It was then decided to start IFX at the standard dose (5 mg/kg) that was reinfused at the same dose after 6 days due to clinical worsening. During the remaining 7 days of hospitalization, he achieved clinical response, in association with partial parenteral nutrition sup-port, completing the induction phase in 13 days. Three years after this episode, he remains in disease remission under IFX standard maintenance plan.

Discussion/Conclusion

In this case series, we aim to illustrate 3 different types of patients and settings according to presentation and disease duration where ASUC is possible. Also, due to the absence of formal guidelines for IFX accelerated or intensified dose regimens, different strategies were considered depending on the episode’s and individual’s characteristics. Both accelerated and dose-intensified approach was used for the most severe case where it was observed rapid progression to toxic megacolon in a young female. On the other hand, a more cautious plan with standard dose acceleration was chosen for the older patient. It should be underlined that, although cyclosporine provides similar short-term outcomes compared to IFX, it is our institution current practice to prefer the anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) drug over the calcineurin inhibitor because of its easiness of use, the transition to the maintenance phase, and the less complex adverse event’s profile.

ASUC is a medical emergency and a potential life-threatening condition. Approximately 1 in 5 patients with UC will face an acute exacerbation that requires hospitalization, often at the time of disease onset [11]. As the Truelove and Witts criteria remain the current severity stratification tool over time, also corticosteroids keep their role for decades as the cornerstone treatment for ASUC with response rates around 67% [12]. For the remnant portion of patients, in the absence of clinical improvement, although surgery must be taken into consideration, medical rescue treatments, including cyclosporine and IFX, can be used with proved efficacy [5].

In this setting of patients, IFX is reported to achieve response rates of 44-75%, although early colectomy rates remain relatively high, between 24% and 48% [13-15]. As previously mentioned, the best IFX induction regimen for salvage therapy is not yet well determined due to lack of supporting literature comparing different strategies, although accelerated regimens seem superior taking into account early colectomy-free survival [5]. Therefore, the approach chosen by each healthcare provider team still depends on the institution experience and some of the patient’s characteristics and perceived risks.

There are some pathophysiological and pharmacokinetic factors that provide a rationale for the use of intensified or accelerated strategies in these severe cases. High inflammatory burden, or by other words disease severity, in ASUC translates into high TNF circulating levels. The clearance of IFX is directly associated with TNF in the systemic circulation, mainly due to the formation of immune complexes and consequent faster proteolytic degradation by the reticuloendothelial system [10]. Additionally, a study by Brandse et al. [16] clearly showed that high levels of IFX in stools of patients with UC were associated with nonresponse to treatment, especially in the severe cases, suggesting a role for repeated infusions to counterbalance monoclonal antibodies fecal loss. The damage of the intestinal epithelial barrier due to extensively ulcerated mucosa is also known for being responsible for protein loss and high incidence of hypoalbuminemia; therefore, it is reasonable to use albumin as a biomarker of drug clearance. The serum level of albumin and C-reactive protein (CRP) reflect the inflammatory status in daily practice, being associated with poorer outcomes, such as early and late colectomy [17], and recently a uni-center-based group proposed a protocol based on CRP/albumin ratio at presentation for the decision of intensified dose use and CRP at day 3 for accelerating dosing [18].

The results of this last single-center retrospective study did not detect a significant difference on early colectomy rates in those exposed to accelerated and standard strategies; however, the cohort for the first group had higher CRP levels at IFX start. This tendency is corroborated by a meta-analysis by Nalagatla et al. [19], where no association is found between accelerated IFX induction therapy and lower rates of colectomy; however, as a retrospective study, the possible bias of different disease severity in both groups might play a role in the final results. Additionally, another systematic review and meta-analysis examining the impact on colectomy-free survival of different IFX induction dosages in ASUC conclude that the results were not statistically different between the standard induction group versus the accelerated or intensified induction dose groups, but again the meta-regression performed revealed higher CRP and lower albumin levels in the intensified group, both of these two prognostic factors being associated with higher risk of colectomy [20]. Partially pointing in an opposite direction, Gibson et al. [9] performed a retrospective analysis of a small group of patients with ASUC, showing that an accelerated induction may bring benefits in the shorter term with lower colectomy rates during induction, although no differences in colectomy during follow-up were seen.

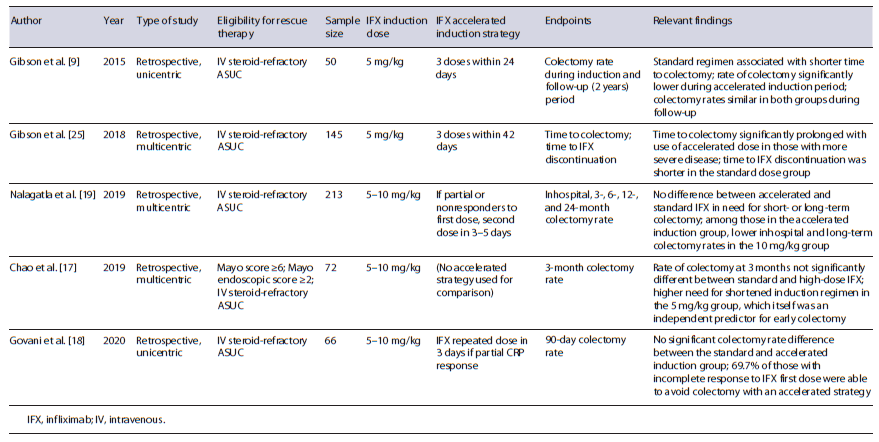

As it becomes clear, there is much need for a robust randomized clinical trial that could unveil the beneficial outcomes of an accelerated or intensified induction strategy, currently used in a heterogeneous and irregular man-ner, comparing to standard regimens originated from pivotal studies (Table 1). Thus, we are eagerly looking forward to the results of the PREDICT-UC (Clinicaltrials. gov: NCT02770040), the only controlled trial of IFX dosing in ASUC, knowing that some questions will remain unanswered. Other aspects like identification of IFX induction levels threshold or additional clinical predictors which could indicate the need for either accelerated or intensified strategies should also be pursued. To date, there are still insufficient data to indicate what is the target trough level during ASUC treatment and consequently the role for TDM becomes unclear. A single study identified IFX serum concentrations of <16.5 and <5.3 μg/mL at week 2 and 6, respectively, as independent predictors for colectomy [21]. Curiously, it was also shown by Ungar et al. [22] that primary nonresponders did not have lower IFX levels compared to responders at week 2; however, a significant difference was seen at week 6. This points to the fact that pharmacokinetics is not the only driver for induction and that TDM role is limited to auxiliate on the assumption of treatment failure, when no clinical improvement is registered despite high IFX serum concentrations, rather than being a tool to pursuit a optimal value.

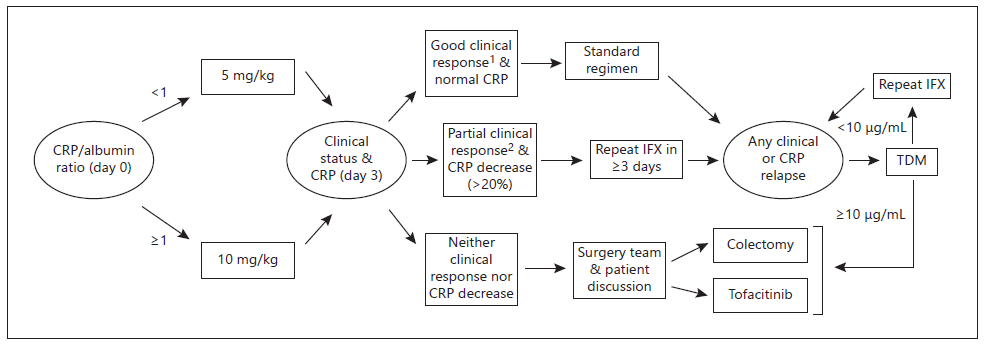

Taking in consideration what we found wiser from each protocol of accelerated regimens used in the studies available to date, we propose a possible algorithm of action in the steroid-refractory ASUC setting (shown in Fig. 4). Additionally, we considered as a possible salvage medical treatment option the rapidly acting janus kinase inhibitor, tofacitinib, although it is still controversial and lacking supporting evidence. The biggest retrospective study to date by Berinstein et al. [23] evaluating the effect of high-dose tofacitinib (together with corticosteroids) in biologic-experienced ASUC patients confirmed its beneficial effect on reducing the 90-day colectomy rate. Similarly, a case series published in 2022 revealed that 4 out of 5 IFX-refractory ASUC patients responded to high-dose tofacitinib, all remaining colectomy free at day 90 [24]. In the near future, we hope that recognition of in-flammatory pathways specific for each patient can modulate therapeutic approaches bringing to clinical practice the goal of personalized medicine.

Fig. 4 Proposed decision algorithm for steroid-refractory acute severe colitis. 1<4 bowel movements/day and no rectal bleeding. 2Significant improvement on number of bowel movements/day and resolution of rectal bleeding. CRP, C-reactive protein; IFX, infliximab; TDM, therapeutic drug (IFX) monitoring