Introduction

Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) is an inherited autosomal-dominant condition caused by a mutation of the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) gene, on the long arm of chromosome 5 [1]. It is marked by a high incidence of colorectal adenomas and cancer. Nevertheless, with adequate screening and prophylactic measures regarding colorectal cancer, duodenal disease has emerged as one of the most important causes of morbidity and mortality in affected patients [2]. Duodenal adenomas (DAs) occur in more than 90% and duodenal cancer in 3-5% of FAP cases [3-6]. The adenoma-carcinoma progression in this location may take up to 15-20 years [7]. Specific regions of the APC gene may be associated with severe disease, due to clustering of somatic mutations, and loss of the wild-type allele [2, 8].

International guidelines advocate regular endoscopic surveillance of the duodenum. Risk stratification, follow-up intervals, and therapeutic approaches are determined according to the Spigelman classification [9], which considers polyp number, size, and histology [9-14]. Excision is recommended for non-ampullary (and some ampullary) adenomas ≥10 mm [14], considering the balance between the risk of endoscopic/surgical resections and the risk of developing duodenal carcinoma. The chosen method is often endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR), which has proven to be safe and effective [15-18]. Significant recurrence rates have been reported, although it is not always straightforward whether they are true recurrences or simply disease progression [16-21]. Furthermore, despite these recommendations, it remains unknown whether DA resection truly changes the natural history of cancer risk since there is an underlying field defect in the duodenum [22].

When invasive disease is suspected, surgical approaches should be considered [14]. These include pancreas-sparing duodenectomy and pancreatoduodenectomy, which offer definitive therapy in preventing duodenal carcinoma, or segmental duodenal resection, for patients with dominant or limited disease, where removing a short segment allows safe endoscopic surveillance/treatment of the remaining bowel. Nevertheless, adenomatous disease may recur in the remaining small bowel, and these patients must be kept under regular surveillance [23, 24].

Additionally, medical treatment using the cyclooxygenase inhibitors sulindac and celecoxib has been studied, yielding conflicting results - due also to significant side effects, their use is not recommended in Europe [25-30]. The aim of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of endoscopic excision of large DAs in patients with FAP and to assess results in light of the most recent guidelines.

Methods

A retrospective study was developed in the familial cancer clinic of an oncological centre, where 151 families with FAP are currently accompanied. FAP families’ files from the familial cancer clinic were reviewed and all FAP patients submitted to endoscopic resection of DAs with at least 10 mm greatest axis, from January 2010 to February 2021, were included. These procedures were described as therapeutic endoscopies.

FAP patients undergo regular endoscopic surveillance according to international guidelines, having their first upper gastrointestinal endoscopy at the age of 20-25 or earlier in case of colectomy before 20 years old. Follow-up intervals are determined according to the Spigelman classification [9], which considers the number, size, and histological characteristics (architecture and dysplasia grade) of duodenal polyps. Spiegelman stage is then calculated by summing the points attributed to these criteria and patients with Spigelman stage 0/I, II, III undergo endoscopy every 5, 3, and 1 year, respectively; those with Spigelman stage IV must be considered individually, undergoing surgery or surveillance every 6 months. Surveillance intervals may be shortened after removal of polyps with higher risk of recurrence, such as those harbouring high-grade dysplasia or with a villous histology, especially if removed piecemeal. This is considered case by case.

Study Procedures

The exams were performed under propofol sedation by an An-aesthesiologist, in the Endoscopy Unit of the Gastroenterology Department of our institution in case of non-ampullary adenomas or in a tertiary hospital with expertise in endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in case of ampullary adenomas. Endoscopes and duodenoscopes belonged to Olympus series 190 and 180, respectively. EMR was usually performed after submucosal injection of a solution containing patent blue (25 mg/mL), adrenalin (1:100,000), and Gelafundin, but decision was made case by case, namely, in ampullary tumours, where submucosal injection was not always necessary. The choice of the snare varied according to endoscopist’s preference (10-25 mm snares were available). Current settings were cutting and coagulation of 120 W - Pulse Cut Slow (ESG-100, Olympus Inc., Tokyo, Japan) for non-ampullary lesions or Endocut 2 60 W (ICC 200, Erbe, Tübingen, Ger-many) for ampullary tumours.

Results

Study Population Characteristics

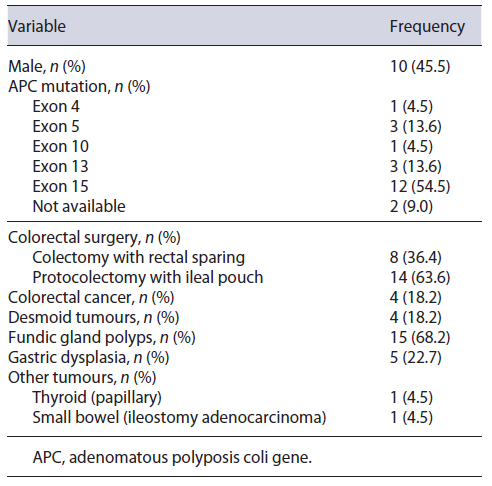

In a total of 151 FAP families, 22 patients from 21 families met the inclusion criteria (DAs with at least 10 mm greatest axis resected in the study period): 54.5% of the patients were female (Table 1), with a median follow-up time of 8.5 (IQR: 5.8-12.3) years after the first endoscopy and 3.7 (IQR: 1.0-5.3) years after the first therapeutic endoscopy. Most germline APC mutations occurred in exon 15 (54.5%). Eight (36.4%) patients had known family history of DAs. The highest Spigelman stage found in these relatives was I, II, III, and IV in 1, 2, 1, and 4 cases, respectively. Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The first screening upper endoscopy happened at 38.0 years of age (median) (IQR: 28.8-52.3) in the study population and DAs were detected in the first exam in 18 (81.8%) of them - staged as Spiegelman I, II, and III in 3, 13, and 2 cases, respectively.

Endoscopic Therapeutic Procedures

First therapeutic endoscopy (resection of ≥10 mm duodenal polyps) occurred at a median age of 41.0 (IQR: 33.0-58.2) years, and 9.1% (n = 2), 40.9% (n = 9), 45.5% (n = 10), and 4.5% (n = 1) of the patients were staged as Spiegelman I, II, III, and IV, respectively. The median time interval between the first screening endoscopy and the first therapeutic endoscopy was 60.3 (±39.1) months, corresponding to a median number of three endoscopies (IQR: 1-5) during that period, in which smaller adenomas were resected in 15 patients (68.2%).

After the first therapeutic endoscopy, a new procedure was required in 12 (54.5%) patients, once in 5 cases, twice in 4, three times in 2, and five times in 1 (median number of therapeutic endoscopies = 2, IQR 1-3), corresponding to a total of 46 therapeutic endoscopies and 50 lesions removed. The median time interval between therapeutic procedures was 20 (IQR: 14-23) months.

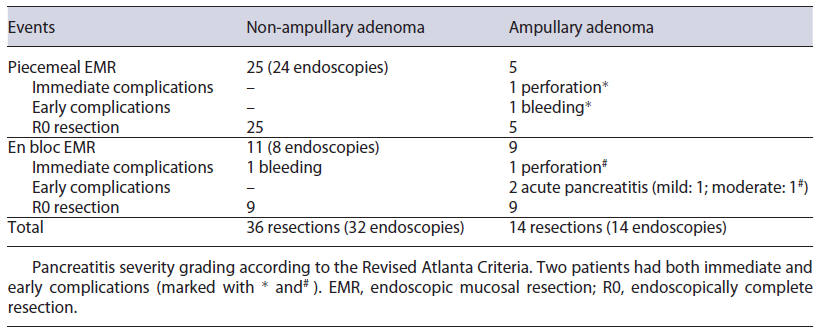

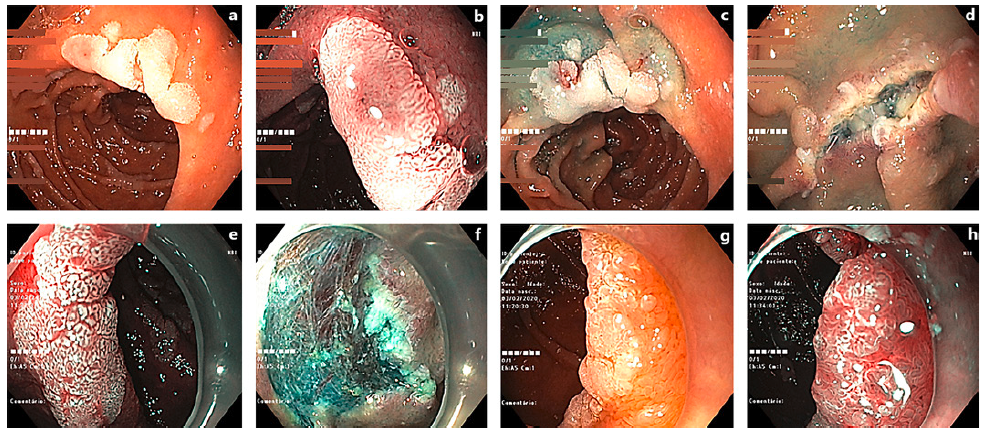

Most therapeutic procedures (69.6% of the procedures) included resection of only one large (≥10 mm) adenoma. The largest adenomas had a median size of 15 mm (IQR: 10-18 mm). The most frequently used technique was piecemeal and en bloc mucosectomy for non-ampullary and ampullary adenomas, respectively (Table 2). Prophylactic defect closure with clips was performed after resection of a 15 mm ampullary tumour and two non-ampullary lesions of 10 and 18 mm; visible vessels were coagulated with snaretip soft coagulation after resection of a 30 mm non-ampullary adenoma. Illustrating pictures can be seen in Figure 1. In 2 cases, resection was considered endoscopically incomplete - one due to scarring in previous resection site and the other due to difficult positioning. These patients were re-evaluated 3 and 5 months later and what was thought to be the residual lesion was successfully removed with cold snare in one and with biopsy forceps in the other case. Further endoscopic follow-up was per-formed annually and none developed adenocarcinoma. Complications occurred in 8.0% (n = 4) of the resected lesions - 3 after ampullectomy and one after a flat lesion mucosectomy (Table 2).

Fig. 1. Examples of resected DAs. a A 12-mm lesion (Paris 0-IIa) in white light examination (WLE). b Same lesion under narrow band imaging (NBI). c After submucosal injection. d During the resection procedure. e 15-mm DA (Paris 0-IIa) in WLE. f Post-polyp resection. g 12-mm lesion (Paris 0-IIa) in WLE. h Under NBI.

Two patients had both immediate (first 24 h) and early (first 7 days) complications; the others had early complications. Immediate complications consisted in intraprocedural bleeding after non-ampullary tumour resection, and perforation after ampullectomy, successfully managed endoscopically. Early (during the first week after the intervention) complications included 1 case of bleeding in a patient who had prophylactic defect closure with through-the-scope clips after ampullectomy, controlled in a repeat endoscopy; 2 cases of acute pancreatitis; one perforation after ampullary tumour resection that was undetected during the procedure. Both pancreatitis occurred after ampulloma resection, despite prophylactic pancreatic stent placement. According to the Revised Atlanta Criteria, one was mild and the other was moderate due to local complications. The latter happened in the same patient in whom a duodenal perforation was diagnosed more than 24 h after the procedure. This patient underwent surgery, with construction of a feeding jejunostomy and pancreatic necrosectomy. He did not require organ support and had a favourable outcome.

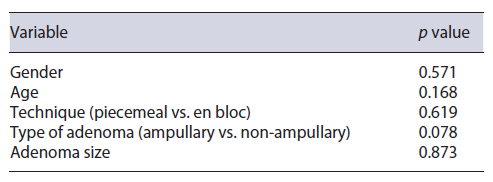

Occurrence of complications was not significantly associated with the technique (piecemeal vs. en bloc mucosectomy) (p = 0.619), type of adenoma (ampullary vs. non-ampullary) (p = 0.078), or adenoma size (p = 0.873) (Table 3). Histology revealed adenomas harbouring low-grade dysplasia in 89.1% (tubular adenomas 76.1%, tubulovillous 13.0%); high-grade dysplasia in 4.6% (n = 2) of cases; no adenocarcinomas were found.

One patient underwent elective duodenopancreatectomy, which did not harbour duodenal cancer. This patient had Spiegelman stage IV disease with three large (>30 mm) lesions that were considered to have a high risk of recurrence/treatment failure after endoscopic resection - one involving the bulbus with a bulky sessile component, one in the transition to the second portion of the duodenum, and the other adjacent to the papilla, close to a fibrotic area of previous resections. All other patients remain under active surveillance.

Discussion

Adenomatous duodenal disease is a known morbidity factor in FAP patients. Endoscopic resection of DAs has a high success rate, with reported complete resections in 86-100% of the cases [16, 21, 31-33]. Even though reported recurrence rates are 10-37% [18, 31-33], the natural history of DAs in FAP patients makes it difficult to distinguish disease progression from local recurrence. In our series, most patients required 2 therapeutic endoscopies during follow-up, reflecting this characteristic.

Endoscopic resection was a safe technique in our series, with an 8.0% complication rate, but with most cases amenable to conservative or endoscopic approaches. This rate is similar or even lower than that reported in other series, and it is also similar in terms of severity of the adverse events. As stated in the literature, most complications occurred after resection of ampullary adenomas, even though it did not reach statistical significance, probably due to our series’ small numbers. Particularly, acute pancreatitis occurred in 2 of 14 ampullary tumour resections despite pancreatic stent placement, in line with previous reports [18, 34-36]. Notably, intraprocedural bleeding rates were lower than expected from literature review [31, 32, 37].

The duodenum remains a challenging location for endoscopic therapy and mucosal resection is the first-line endoscopic resection technique for non-malignant large DAs [38, 39]. However, when EMR is not feasible and considering the risks associated with the surgical alternatives, endoscopic submucosal dissection can be considered by experienced endoscopists [39, 40]. In our series, duodenal surveillance started later than recommended in international guidelines since a significant number of patients were referred to our clinic only in adult age after a CRC diagnosis in the patient or in a family member.

There were no cases of duodenal cancer during follow-up, reflecting the effectiveness of endoscopic surveillance according to the Spigelman stage. Therefore, this work further strengthens current recommendations of DAs surveillance in FAP patients and legitimates the choice of endoscopic resection as the first-line treatment.