Introduction

Spontaneous esophageal perforation, known as Boerhaave’s syndrome (BS), is a predominantly longitudinal perforation of the distal esophagus due to forceful emesis. It is associated with a high mortality rate (20-40%) due to delay in recognition and treatment [1]. The classical triad of subxiphoid retrosternal pain, vomiting, and subcutaneous emphysema is present in only a few patients, posing a difficult diagnostic challenge. In fact, in a few patients, the injury occurs silently, without any relevant medical history [2]. The esophagogram may aid diagnosis, but it has a false-negative rate of 10%. In such cases, CT with orally administered water-soluble contrast provides the best diagnostic tool [3].

The BS management includes the resolution of the source of the infection, thoracic and mediastinal debridement, and surgical or nonsurgical closure of the defect. With the development of endoscopic procedures during the last decades, endoscopy represents a minimal or significantly lower burden in the diagnosis of BS and its treatment [4]. Endoscopic stenting and over-the-scope clip (OTSC) have been reported as an alternative to surgery in selected cases, with good results [5]. Here, we report 2 cases of successful endoscopic management of a spontaneous esophageal rupture using OTSC.

Case Reports

Case 1

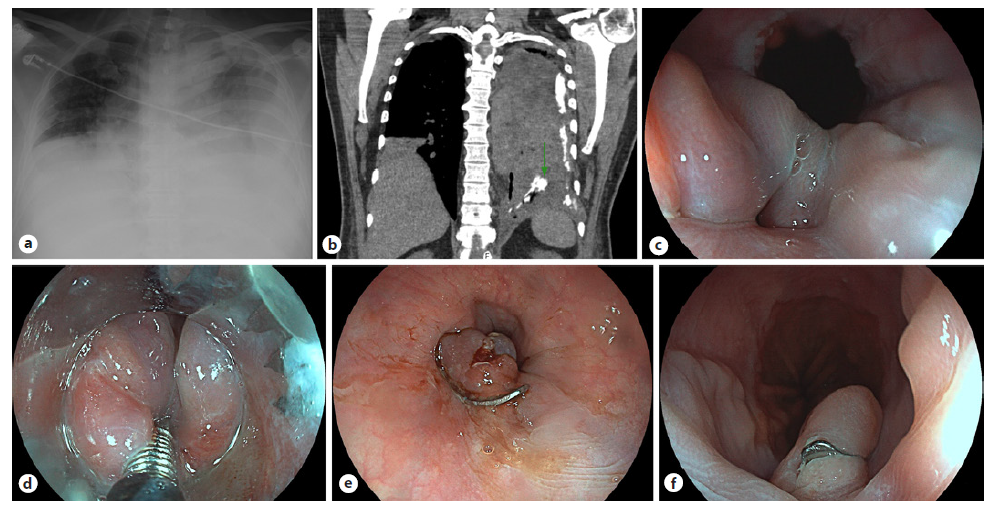

A 49-year-old man was transferred from a peripheral hospital following an episode of meat bone impaction during lunch which could not be removed by upper gastrointestinal endoscopy (UGE) on that Unit. The impaction was associated with spontaneous and self-induced retching. The patient was submitted to a rigid esophagoscopy under deep sedation with successful removal of the bone located immediately below the superior esophageal sphincter, with no evidence of severe wall damage. During the first day of recovery, the patient developed left and anterior severe thoracic pain associated with respiratory failure. Initial chest radiography revealed a left-sided pleural effusion and pneumothorax (Fig. 1a). Broad-spectrum antibiotics and oxygen therapy were immediately started. A thoracic catheter was inserted, allowing the drainage of a cloudy serous fluid with increased amylase, and positivity to methylene blue challenge, suggestive of a gastrointestinal tract perforation. Oral contrast cervicothoracic CT confirmed pneumomediastinum and left empyema with contrast leak at the lower esophagus level (Fig. 1b). After a multidisciplinary meeting, a UGE was performed on the 4th day, showing superficial laceration at the proximal esophagus related to the recent impaction and a 10-mm recent esophageal perforation in the distal esophagus (Fig. 1c). An 11-mm t-type OTSC (Ovesco, Tübingen, Germany) was selected. The perforation edges were grasped and captured into the cap using a harpoon device (OTSC anchor®) (Fig. 1d). The clip was then released and the perforation hole was successfully closed (Fig. 1e). On the fourth day after clipping, an esophagogram showed no leak, and oral intake was started. The patient was discharged on the 15th day postendoscopic closure, clinically well with resolution of empyema. Three months later, revision UGE revealed OTSC in situ (Fig. 1f) with effortless passage into the stomach. The patient remains clinically well on a complete diet.

Fig. 1. a Chest radiography showing left pneumothorax and pleural effusion, with complete opacification of the left hemithorax and the trachea shifted to the right. b Cervicothoracic CT revealed an oral contrast leak at the distal esophagus (arrow). c Upper gastro-intestinal endoscopy showing a hole in the distal esophagus. d Perforation’s edges were captured with the OTSC anchor® into the cap, before clipping. e Perforation hole was successfully closed using OTSC. f Three months later, UGE revealed OTSC in situ, with no signs of esophagus obstruction.

Case 2

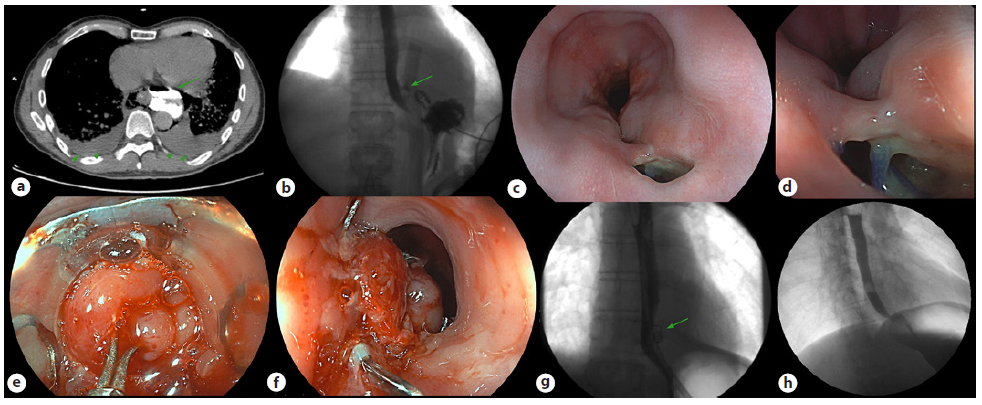

A 50-year-old man with no relevant medical history was admitted to the Emergency Department with severe chest pain after an episode of vomiting. A cervicothoracic CT showed an exuberant pneumomediastinum, extending to the muscular planes of the neck and presenting subcutaneous emphysema. The passage of oral contrast to the mediastinum confirmed the diagnosis of BS (Fig. 2a).

The patient was initially submitted to surgical treatment, with esophageal suture and drainage of the mediastinum. Thereafter, he was admitted to the intensive care unit, under invasive mechanical ventilation, antibiotics, and prolonged need for aminergic support. On the 12th day, an esophagogram showed persisting contrast leakage from the left wall of the distal esophagus in close communication with the multicapillary drain placed in the mediastinum (Fig. 2b). A UEG was performed showing two adjacent holes at the level of the distal esophagus, the largest with 12 mm of diameter, through which it was possible to observe suture points and the multicapillary drain (Fig. 2c, d).

It was decided to close it with 11 mm t-type OTSC using the OTSC anchor® with complete closure encompassing both holes (Fig. 2e). At the end of the procedure, a mild reduction of the esophageal lumen at the OTSC level was observed (Fig. 2f).

There was a favorable clinical and analytical response in the following days, with the progressive withdrawal of all supportive measures. After 10 days, the esophagogram revealed the OTSC in place and no signs of contrast leakage (Fig. 2h). The patient was discharged after 15 days tolerating an oral diet. Nine months after the procedure, the patient was asymptomatic and repeated an esophagogram and cervicothoracic CT, showing no signs of esophageal leakage or OTSC presence.

Fig. 2. a Cervicothoracic CT showing oral contrast extravasation from the esophagus into the mediastinum (arrow) and bilateral pleural effusion (arrowheads). b Esophagogram performed 12 days after surgery showing persistence of oral contrast extravasation (arrow) near the left distal esophagus wall. c, d Endoscopic view of two adjacent holes in the distal esophagus, being possible to look at some suture points. e Holes’ edges being pulled by OTSC anchor® into the cap, before clipping. f Esophagus after OTSC application, encompassing both holes. g Ten days postprocedure esophagogram showing OTSC in situ (arrow) with no contrast extravasation or signs of esophagus obstruction. h Nine months postprocedure esophagogram with no signs of OTSC, esophageal leakage, or esophageal stricture.

Discussion

Although no consensus exists regarding the best strategy, the current treatment of BS should be fitted to the patient’s presentation, the type and extent of the rupture, the delay to the diagnosis, and the consequent viability of the esophageal wall [4]. Conservative management includes intravenous broad-spectrum antibiotics, restriction of oral intake, derivation of nasogastric content, pain control, gastric acid suppression, and hemodynamic monitoring and support. However, due to the high mortality associated with BS, an exclusive conservative approach can only be considered plausible under the following conditions: perforation already 5 days old and absence of signs of severe sepsis, esophagogram showing a contained perforation that drains freely back into the esophagus, and absence of contamination in the pleural space [6]. Unfortunately, this is hardly the rule, frequently occurring a more severe presentation and a worse prognosis due to septic complications.

Classical surgical intervention consists on open primary esophageal repair (laparotomy and/or thoracotomy). General principles of this approach include excellent exposure, debridement of nonviable tissue, closure of the defect, use of buttress to reinforce esophageal sutures, and adequate tube drainage. Overall mortality after open surgery for esophageal perforation is around 20%; however, prompt surgical intervention can reduce that mortality by 50% [7].

Less invasive techniques in the setting of esophageal surgery, such as laparoscopy and left video-assisted thoracoscopy, may be beneficial in minimizing operative surgical trauma, reducing postoperative pain, improving ventilation, and facilitating early mobilization. Early presentation, stable vital signs, and expertise of the surgical team are required [4].

Given the increasing improvements in advanced imaging, diagnosis, and therapeutic techniques, endoscopic treatment has become an effective and valid alternative to surgery in many clinical conditions, including BS in selected patients. Most data about the endoscopic approach to esophageal perforation come from the endoscopic management of iatrogenic perforation during endoscopic procedures. The most decisive factor in the selection of endoscopic modality seems to be the size of the esophageal wall defect. Through-the-scope clips have shown to be effective for small defects (less than 10 mm), while OTSC can be applied in moderate-size perforations up to 20 mm. Larger perforations in the mid and lower esophagus can be managed with the temporary placement of self-expandable metal stents [8].

Endoscopic vacuum therapy (EVT) and more recently endoscopic suturing should also be considered in larger defects. EVT uses negative pressure to absorb secretions and promote wound healing by secondary intention, having proved to be especially useful in patients with postoperative anastomotic leaks. The evidence on endoscopic suturing is still scarce and there are technical difficulties in applying it to the esophagus [9, 10].

Early perforations (those diagnosed within 24 h) are described as having the best outcomes, as tissues have no edema, facilitating defect closure, and there is no active bacterial infection in the thoracic cavity or mediastinum. Therefore, apart from the perforation size, the timing of the intervention and the presence of inflammation or poor surrounding tissue quality with ischemic/necrotic wound edges may be relevant factors to take into account in the selection of the endoscopic approach. Even so, there are no comparative studies between different endoscopic modalities.

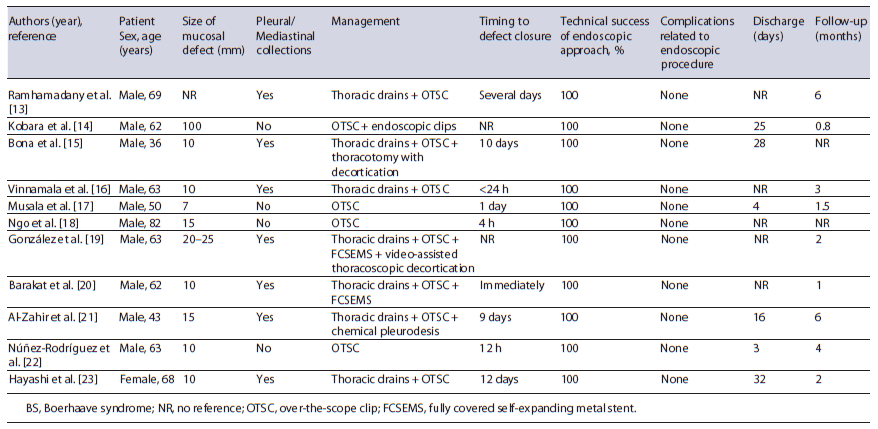

Concerning BS, case series also demonstrate that endoscopic management represents a valuable option [11, 12]. Table 1 summarizes the main characteristics and pa-tients’ outcome of several case reports of BS managed with OTSC published over the last decade, emphasizing the efficacy of the procedure with no reported direct complications [13-23].

Table 1. Baseline characteristics and individual outcomes of cases of patients with BS managed with OTSC

In the 2 cases presented, the size of the perforations (and the complexity in case 2), the time elapsed since the presumed occurrence and the associated thoracic manifestations, led to the choice of OTSC as the most adequate approach to secure an effective transmural closure. However, a self-expandable metal stent has also proven to be appropriate in this context, covering esophageal leaks and preventing fistula formation. Furthermore, with the possible exception of EVT, the endoscopic management of BS complicated with mediastinal or pleural collections should always be combined with percutaneous or surgical drainage of the extraesophageal contamination, as was the case [4]. In conclusion, the standard of care for patients with BS should be based on a multidisciplinary and case-to-case personalized approach including conservative, endoscopic, and/or surgical treatment. Our case re-port highlights that esophageal defect closure with OTSC may be a suitable minimally invasive option in a delayed scenario of BS, both as primary and rescue therapy, provided that it is technically feasible and mediastinal or pleural infection are sought and adequately drained.