Introduction

Anastomotic leaks (AL) are one of the most worrisome complications in the early postoperative period, either after a total gastrectomy or an esophagectomy [1, 2].

The AL incidence after esophagectomy ranges from 5 to 40% [3-5]; for AL post gastrectomy, several groups have reported rates of 5-7% [6, 7].

AL results in high mortality, often requiring repetitive therapeutic interventions and is associated with prolonged hospitalization [7, 8]. Early diagnosis and timely treatment are of utmost importance to avoid serious AL-related complications. However, early recognition of AL can be difficult due to the different clinical scenarios, often indistinguishable from symptoms caused by physiological postoperative inflammatory response or infection [9].

AL treatment options include conservative approach, endoscopic interventions, or surgery. The nonsurgical approach should be the initial strategy, reserving surgical reintervention for conservative measures’ failure. Depending on the size and location of AL, a variety of endoscopic procedures can be selected, namely: endoscopic clips (mainly over-the-scope clips - OTSC), self-expandable metal stents (SEMS), endoscopic vacuum therapy and fibrin glue [10-12]. SEMS play a significant role in the management of these patients. There have been several reports of AL endoscopic treatment with SEMS placement [13, 14]. Only one case report described the use of an esophageal Mega-Stent in a patient with postesophagectomy gastropleural fistula [15]. Herein, the authors describe two examples of the utility of Mega-Stent in AL management.

AL results in high mortality, often requiring repetitive therapeutic interventions and is associated with prolonged hospitalization [7, 8]. Early diagnosis and timely treatment are of utmost importance to avoid serious AL-related complications. However, early recognition of AL can be difficult due to the different clinical scenarios, often indistinguishable from symptoms caused by physiological postoperative inflammatory response or infection [9].

AL treatment options include conservative approach, endoscopic interventions, or surgery. The nonsurgical approach should be the initial strategy, reserving surgical reintervention for conservative measures’ failure. Depending on the size and location of AL, a variety of endoscopic procedures can be selected, namely: endoscopic clips (mainly over-the-scope clips - OTSC), self-expandable metal stents (SEMS), endoscopic vacuum therapy and fibrin glue [10-12]. SEMS play a significant role in the management of these patients. There have been several reports of AL endoscopic treatment with SEMS placement [13, 14]. Only one case report described the use of an esophageal Mega-Stent in a patient with postesophagectomy gastropleural fistula [15]. Herein, the authors describe two examples of the utility of Mega-Stent in AL management.

Case Report

Case 1

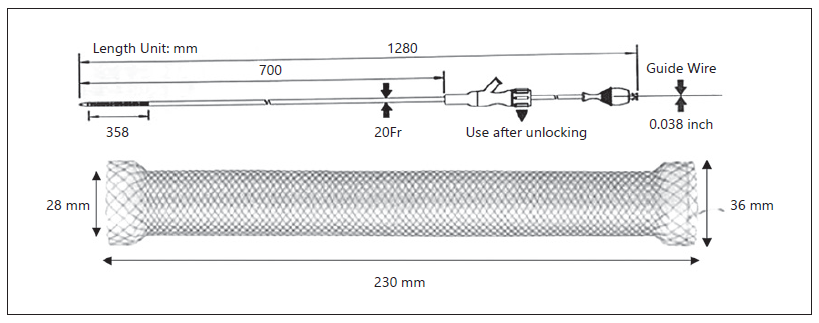

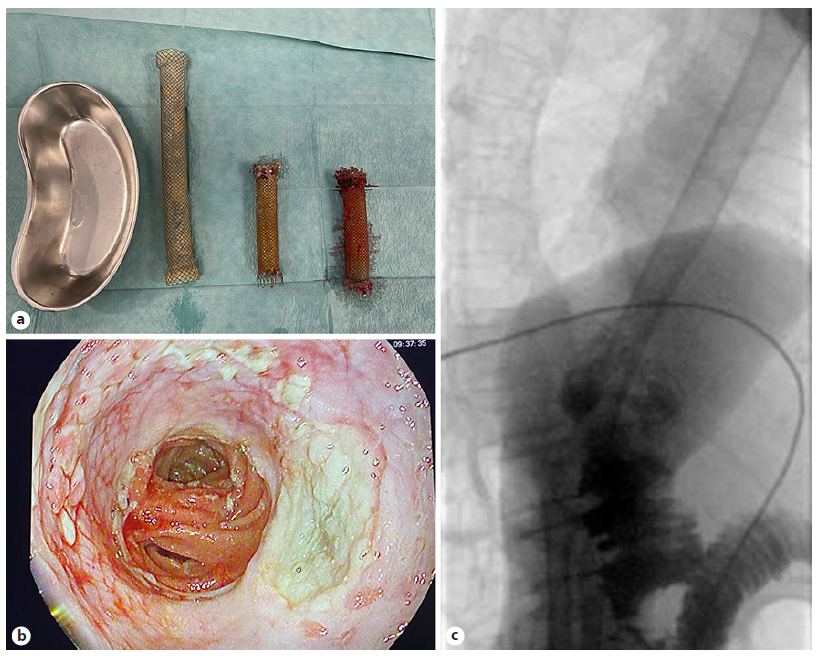

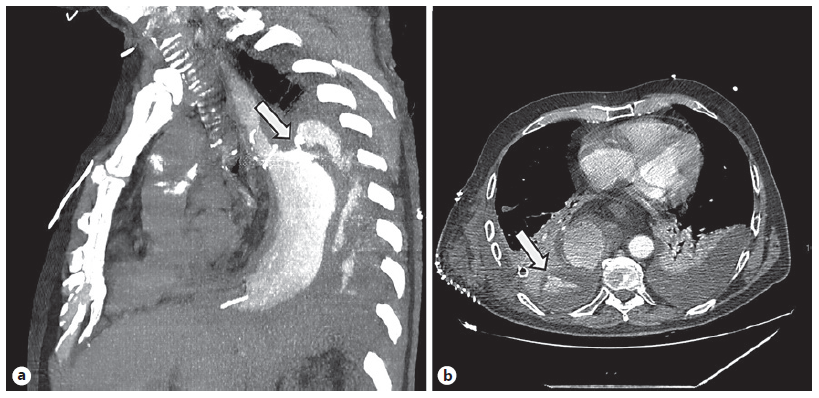

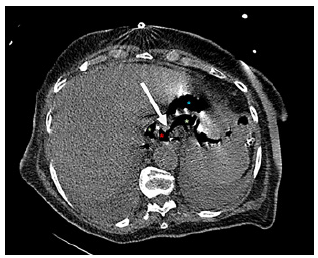

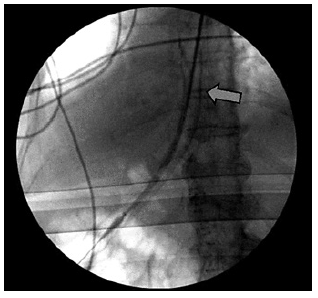

A 67-year-old male was referred to the Surgery Outpatient Clinic with a 4-month history of dysphagia and weight loss. The patient was a former smoker. Other relevant past medical history included squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the head, surgically resected in the previous year, and colorectal cancer diagnosed 10 years before, that underwent right hemicolectomy. The upper GI endoscopy revealed a SCC of the distal esophagus. Clinical staging was cuT3N3aM0, according to computed tomography (CT), endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) and fluorodeoxyglucose positron-emission tomography (FDG-PET) findings. The patient underwent neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy and control CT showed clinical response. Afterwards, an Ivor-Lewis esophagectomy was performed without immediate complications. Two days after the procedure, the thoracic drain poured biliary fluid. Endoscopy with fluoroscopic control was performed, confirming the suspicion of AL of the gastric staple line of the esophagogastric anastomosis (EGA). An OTSC was placed in the dehiscence orifice. The patient started total parenteral nutrition (TPN). Three days later, fever was noted and thoracic CT revealed extraluminal oral contrast from the gastric conduit to the right pleura, confirming the presence of a gastropleural fistula (Fig. 1). Repeated endoscopy identified the OTSC previously placed in situ (Fig. 2a). Immediately below the EGA, in the posterior wall of the gastric conduit, a small orifice was seen, and a fluoroscopic image confirmed extraluminal contrast leakage (Fig. 2b). The previous OTSC clip was removed with a grasp and soft coagulation with Argon Plasma was applied at the orifice margins. Another OTSC was placed over the dehiscence orifice, and no further extraluminal contrast was observed at fluoroscopic evaluation. Given the friability of the tissue surrounding the OTSC and the failed first attempt with this method, we complemented therapy with a fully covered metal stent (FCMS). A Niti-STM MEGATM Esophageal Stent (Mega-Stent) from Taewoong Medical measuring 28 × 230 mm (Fig. 3) was chosen to ensure gastric conduit exclusion and facilitate healing. The proximal end of the stent was anchored in the esophagus and the distal end in the proximal bulbus (Fig. 2c). Three through-the-scope (TTS) clips were also used at the proximal end of the Mega-Stent to avoid migration. The patient improved and subsequent radiologic control showed progressively AL resolution. Several infectious complications significantly increased hospital in-stay length. TPN was maintained during most of the hospital admission. Enteral nutrition was started on the 36th day after Mega-Stent placement and parenteral support was discontinued after 40 days. Before patient discharge, repeated CT confirmed absence of AL and ambulatory endoscopy was scheduled for 6 weeks later to remove the stent which was easily performed with a grasp. Scar tissue was observed in the previous AL location, and no extraluminal contrast was observed at fluoroscopic evaluation, thus confirming successful of endoscopic treatment.

Fig. 1 Computed tomography. a Dehiscence of the gastric staple line of the esophagogastric anastomosis (arrow). b Gastropleural fistula with oral contrast in the pleural cavity (arrow).

Fig. 2 Fluoroscopic image. a OTSC clip (arrow) placed in the first esophagogastroduodenoscopy. b Extraluminal contrast leakage (arrow) from the gastric conduit. c Niti-STM MEGATM Esophageal Stent (Mega-Stent), placed between the esophagus and the bulbus (arrows).

Case 2

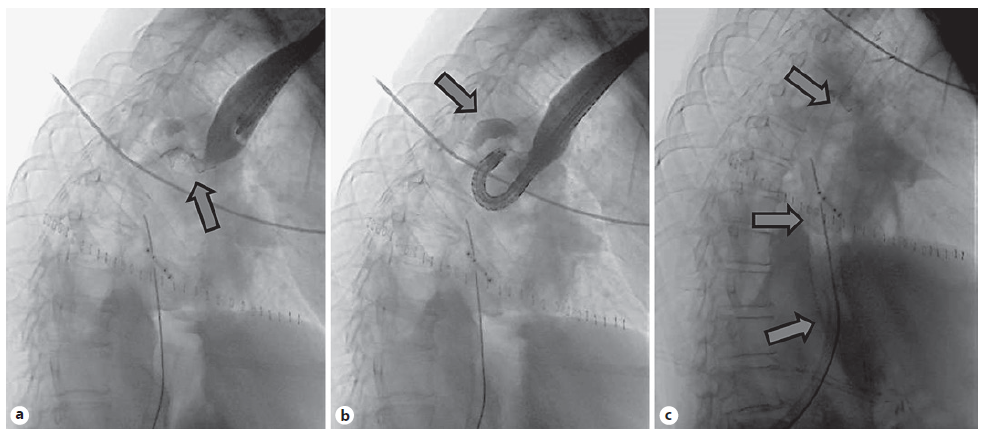

An 86-year-old woman was referred to the Surgery Outpatient Clinic with a 1-month history of low solid food dysphagia. Relevant medical history included left nephrectomy due to tuberculosis and iodine contrast allergy. Endoscopy revealed ulcerated gastric neoplasia, involving the anterior wall of the distal corpus and proximal antrum. Biopsies were consistent with well-differentiated gastric adenocarcinoma. CT and FDG-PET showed local lymph node involvement but no distant metastasis. Staging laparoscopy did not reveal peritoneal metastasis. Given the patient’s good performance status (ECOG-0/Karnofsky-90), total gastrectomy with Roux-en-Y esophagojejunostomy was performed without immediate complications after a thorough informed consent had been obtained. A feeding jejunostomy was also left for immediate nutritional support. On the third postoperative day, the patient presented fever, thoracalgia and dyspnea. Thoracic CT confirmed AL (Fig. 4). Endoscopy did not identify a clear dehiscence orifice. However, at fluoroscopic evaluation, extraluminal contrast was seen at the esophagojejunal anastomosis (EJA) site. A 23 × 125 mm PCMS was placed to cover the EJA (Fig. 5). The patient started TPN. Ten days after surgery, biliary drainage was noted in the thoracic drain. CT demonstrated oral contrast leakage at the proximal end of the PCMS. EGD with fluoroscopic control confirmed minimal extraluminal contrast at the proximal third of the stent. A new 23 × 125 mm PCMS was placed to cover the leakage area, the proximal end located 5 cm above the previous stent, secured with 3 TTS clips. After this intervention, the patient presented clinical improvement. Repeated CT confirmed absence of leakage. She was weaned off TPN, being discharged after 47 days due to several infectious complications. Endoscopic removal of both stents was scheduled for 10 weeks after discharge. Due to granulation tissue on both ends of the PCMS, the endoscopy team decided to place a Mega-Stent to cover both uncovered tops (stent-in-stent technique). Two weeks later, the three stents could be easily removed using a grasp without complications (Fig. 6a). The anastomosis presented no dehiscence (Fig. 6b) and, at fluoroscopic evaluation, no leakage was seen (Fig. 6c).

Fig. 4 Computed tomography showing anastomotic dehiscence (arrow). Red asterisk: esophagojejunal anastomosis. Blue asterisk: jejunum. Green asterisk: extraluminal air.

Fig. 5 Fluoroscopic image of partially covered metal stent placed in the esophagus, covering dehiscence.

Discussion

AL after oncologic surgery is a very serious and challenging problem. Gastrectomy plus lymphadenectomy followed by EJA is the standard treatment for gastric cancer. Despite advances in surgical techniques and perioperative management, EJA leak remains a serious and potentially fatal complication of total gastrectomy [16]. Overall, the mortality rate associated with EJA leak is approximately 30% [7]. Esophagectomy, on the other hand, is a technically challenging procedure, prone to high incidence of complications. AL after cancer resection remains one of the most feared complications, associated with high mortality [17].

Isolated AL can sometimes be successfully managed with conservative treatment, including antibiotics, nil by mouth, nasojejunal tube or parenteral feeding. Several endoscopic approaches including SEMS, endoscopic vacuum therapy and clips have been reported to be useful in treating AL and can result in healing with minimal morbidity [11-14]. Revisional surgery presents a challenge and carries a risk of further complications. However, surgical intervention is sometimes required for refractory AL cases after failed conservative or endoscopic approach. No evidence supporting a specific treatment option for AL has been defined for lacking high-quality studies [18, 19].

Vacuum therapy has shown good results in the literature, but in both our cases, only small dehiscence orifices were observed, without a cavity contacting with esophageal lumen, thus making it an inadequate scenario to apply vacuum therapy. Also, we have little experience with this treatment, as opposed to OTSC and luminal stents. The endoscopic SEMS placement for cases of AL or fistula presents a safe and well-established therapeutic technique, with low overall procedure-related mortality. However, stent migration and failure to completely cover large AL are the main pitfalls of the procedure [20]. The use of multiple or larger stents can be a way of overcoming such limitations. Several reports described the use of a Mega-Stent for managing leaks after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy [21-23]. In fact, the Mega-Stent was developed for management of leaks after sleeve gastrectomy, but the EGA leak presents a similar behavior, thus Mega-Stent is a valid option in this situation. Only one case report described clinical success using a Mega-Stent in a case of postesophagectomy gastropleural fistula [15].

In our first case, the patient underwent an esophagectomy and presented AL in the proximal part of the gastric conduit. The choice of the Mega-Stent arose after a first failed attempt of AL treatment using an OTSC. Considering the abrupt diameter transition between the esophagus and the stomach, a standard sized SEMS would not properly seal the AL. Also, since conventional stents would present a significant migration risk, an esophageal Mega-Stent was selected to ensure gastric conduit exclusion and facilitate healing while minimizing dislodgment, as it could be placed and anchored between the esophagus and the bulbus. Nevertheless, we chose to place 3 TTS clips in the proximal end of the Mega-Stent to guarantee stent fixation. OTSC and endoscopic suturing are recommended to prevent stent migration. Unfortunately, we had no more OTSC with adequate size for this purpose available at that moment in our unit. Furthermore, the placement of an OTSC would be a more expensive strategy just for preventing stent migration. As endoscopic suturing was not available in our center, we considered the placement of TTS clips to be the best choice in this case. The AL was successfully treated.

Regarding the second patient, with an EJA leak after a total gastrectomy, a first PCMS was placed in attempt to treat the AL. The choice of a PCMS was to prevent stent migration. However, one stent could not resolve the AL, so we placed a second PCMS, successfully treating the AL. Stent removal was scheduled 10 weeks thereafter, but due to granulation tissue on both PCMS, we opted to perform a stent-in-stent technique using an esophageal Mega-Stent. The use of a single standard size FCMS would not have enough length to cover both uncovered portions of the previously placed stents. The alternative would be to place two FCMS, either in the same endoscopic procedure or in different endoscopic times and removing them sequentially in two stent-in-stent approaches. In this case, the Mega-Stent proved very useful in this case since we removed all three stents 14 days later without complications. This case illustrates an alternative application of the Mega-Stent in AL management.

The authors believe that the Mega-Stent can be an emerging tool for endoscopic management of surgical AL since it is safe, easy to place, able to treat large AL and reduces the risk of stent migration. It can also be used in stent in-growth cases, avoiding the need for multiple FCMS, thus simplifying the procedure.