Introduction

Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is an inflammatory liver disease of unknown etiology. This condition primarily affects women and is characterized by autoantibodies, hypergammaglobulinemia, interface hepatitis, and plasma cell infiltration. AIH responds well to immunosuppressive therapy, mainly azathioprine and corticosteroids [1, 2].

Patients with AIH frequently exhibit characteristics of a chronic disease, including nonspecific symptoms such as fatigue, nausea, and arthralgias [1, 2]. However, acute-onset AIH has a clinical spectrum ranging from asymptomatic forms to an acute presentation simulating viral or toxic hepatitis or even a fulminant acute presentation [3-6]. Interestingly, most patients with acute-onset AIH exhibit histological features of chronic hepatitis or cirrhosis.

There is no consensus definition of acute presentation of AIH. Yamamoto et al. [7] proposed as definition of this form of presentation a duration of symptoms ≤26 weeks, aminotransferases higher than 10 times the upper limit of normality (xULN), and/or bilirubin higher than 5 mg/dL. In 2019, Rahim et al. [8] proposed that acute presentation of AIH should correspond to acute hepatitis (jaundice ≤26 weeks, without coagulopathy or encephalopathy), severe acute hepatitis (jaundice ≤26 weeks, with coagulopathy and without encephalopathy), and fulminant acute hepatitis (jaundice ≤26 weeks, with coagulopathy and with encephalopathy).

Independently of the definition, acute presentation of AIH corresponds to two different situations: acute exacerbation of chronic AIH, in which patients show clinical and laboratory findings of acute hepatitis and histology of chronic disease, and genuine acute AIH (GAAIH), in which patients exhibit clinical, laboratory, and histological features of acute hepatitis [9, 10]. Since these individuals frequently have low IgG levels, absence or low titers of autoantibodies, and unusual histological characteristics such as centrilobular necrosis in zone 3, diagnosing GAAIH might be difficult [4, 11-15]. Centrilobular necrosis in zone 3 is a common finding in patients with drug-induced acute liver injury [16], acute post-transplant rejection [17, 18], hepatic congestion or ischemia [19, 20], or even acute viral hepatitis. These factors hamper the diagnosis of autoimmune etiology due to low International Auto-immune Hepatitis Group (IAIHG) scores [21]. Furthermore, histological criteria for AIH are not completely clear. The previous published criteria aimed mainly the findings of chronic AIH with abnormalities in portal and periportal regions that cannot always be applied to acute presentation of AIH. More recently, the paper by Lohse et al. [22] defined probable AIH if there is predominance of lobular hepatitis with or without centrilobular necroinflammation associated to at least one of these characteristics: portal lymphoplasmocytic hepatitis, interface hepatitis, or portal fibrosis. These histological criteria include both acute and chronic presentation of AIH, however, without establishing clear histological criteria for genuine acute hepatitis. The present study aimed to identify the prevalence, clinical features, and biochemical and histological response to treatment in patients with GAAIH and compare these cases with patients with acute exacerbation of chronic AIH.

Materials and Methods

Study Population and Data Collection

This hospital-based descriptive study evaluated a prospectively maintained database of patients referred to a tertiary outpatient clinic between 1997 and 2014. It involved patients with acute presentation of AIH. The diagnosis of AIH was based on the criteria of the IAIHG for all patients [21]. Acute presentation of AIH was defined as acute onset of symptoms (≤26 weeks), total bilirubin levels higher than 5 mg/dL, and/or alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels higher than 10 xULN as well as no prior history of liver disease [7]. GAAIH was distinguished from the acute presentation of chronic AIH based on histological findings of mainly lobular hepatitis, with or without centrilobular necrosis, portal and lobular lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory infiltrate, and no degree of fibrosis.

Exclusion criteria were alcohol consumption of more than 20 g/day and evidence of liver disease of other causes (drugs, viral or metabolic causes). Patients presenting with acute liver failure and overlapping syndromes were also excluded.

Initial Assessment and Follow-Up

The patients were submitted to clinical and laboratory evaluation at the disease presentation and during each visit. The visits were scheduled fortnightly at the beginning of follow-up, then monthly, and after that for 3 months. The laboratory tests included measurement of the liver enzymes ALT, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), γ-glutamyltransferase (GGT), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), total bilirubin and fractions, prothrombin time, and protein electrophoresis. ALT, AST, GGT, and ALP are expressed as an index: value obtained/xULN.

Detection of Autoantibodies

Antibodies to the smooth muscle (SMA), antibodies to liver/kidney microsome type 1 and anti-mitochondrial antibodies were identified by indirect immunofluorescence on rat liver, kidney, and stomach tissue sections. Antinuclear antibodies (ANA) were determined by standard indirect immunofluorescence on the imprint and HEp-2 cells. A titer higher than 1:40 was considered to be significant for ANA imprint and 1:80 for HEp-2 cells.

In addition, the other autoantibodies were investigated by immunoblotting: antibodies against soluble liver antigen/liver-pancreas, liver cytosol-specific antibody type 1 (LC1), antibodies to Ro 52 (anti-Ro52), anti-Sp100, and anti-gp210 (Euroimmun, Lübeck, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Patients positive for anti-LC1 were also tested by indirect immu-nofluorescence in rodent tissue.

Treatment Regimen

Patients with AIH were treated with prednisone at an initial daily dose of 50 mg, which was reduced to a daily maintenance dose of 10 mg, in combination with azathioprine at doses of 50-150 mg (mean dose of 100 mg). Either prednisone or azathioprine alone was used in case of contraindication of the combined therapy. Patients non-responsive to conventional therapy regimens were given alternative drugs, such as mycophenolate mofetil, tacrolimus, and cyclosporine.

Biochemical Response

The biochemical response was defined as the normalization of ALT, AST, bilirubin, and gamma-globulins evaluated at 6 months of treatment [23].

Statistical Analysis

Exploratory data analysis included mean, median, standard deviation, and range for continuous variables and number and proportion for categorical variables. Descriptive statistics, graphs, and the specific test for theoretical assumption of normality Shapiro-Wilk were considered to analyze the behavior of continuous variables. In accordance with the variable distribution, the Student’s t test or Mann-Whitney test was used to compare continuous variables between two independent groups; when appropriate, the Pearson χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test was used to compare categorical variables between two independent groups. Statistical analysis was performed using IBM-SPSS Statistics software version 28 (IBM Corporation, NY, USA) and R software. The tests were two tailed, and p values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

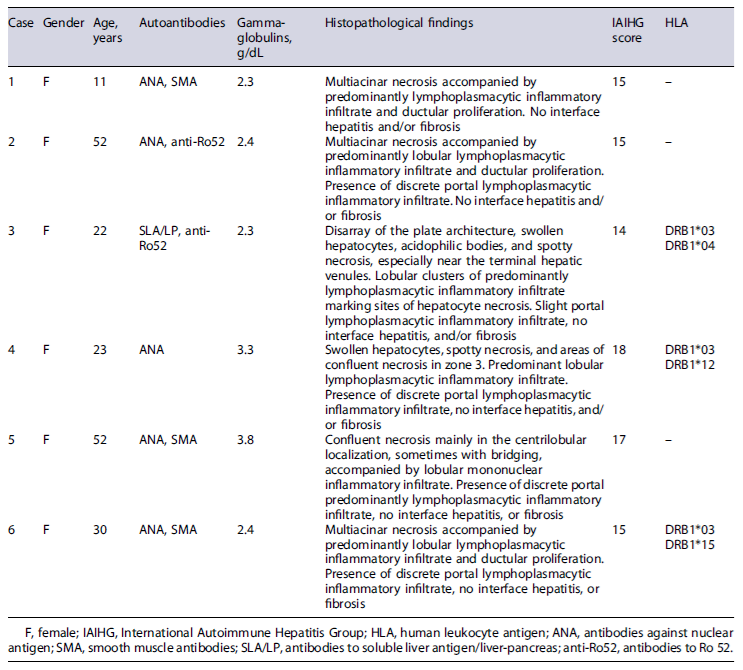

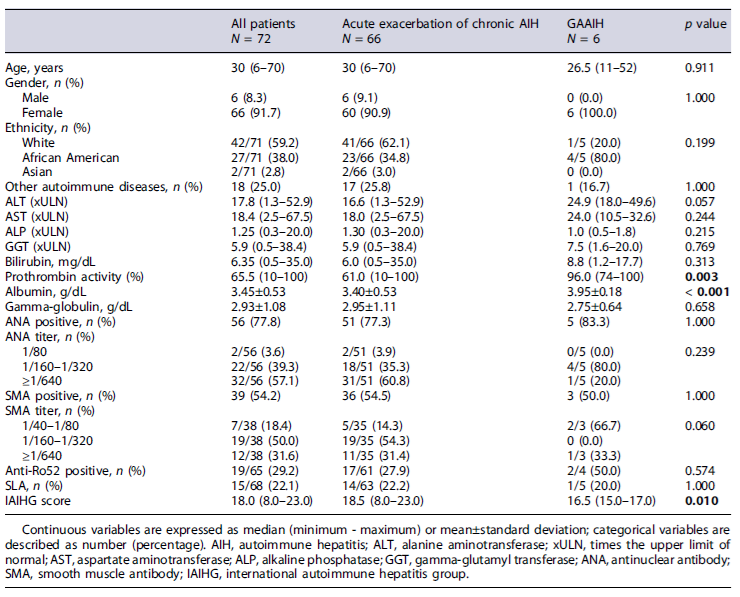

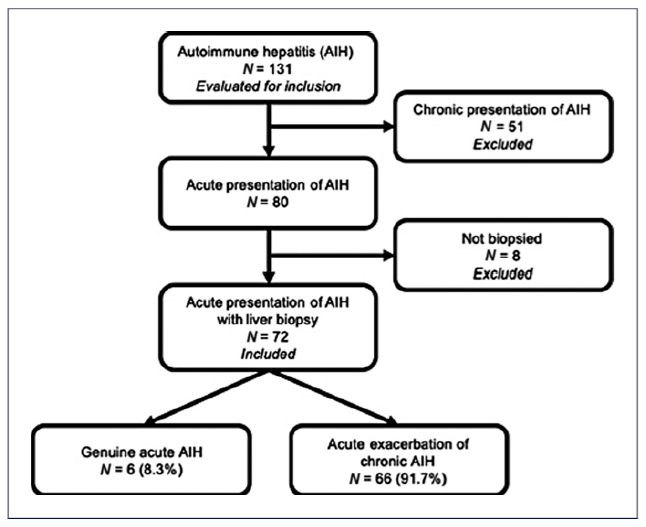

Over 17 years, 131 patients with AIH diagnoses were evaluated for inclusion in the study. Fifty-one patients with chronic AIH presentation and eight others for not having been submitted to a liver biopsy were excluded from the analysis. Thus, 72 patients with acute AIH symptoms were included (Fig. 1). Most patients (93.7%) were females, and the mean age was 32 (6-70) years; 59% of the patients were Caucasian. Only 6 patients (8.3%) presented histological criteria compatible with GAAIH; these patients’ clinical features are shown in Table 1. Sixty-six patients (92%) had a histological diagnosis of chronic hepatitis and 32 presented with liver cirrhosis.

Fig. 1. Flow diagram of the potential candidates for participation in the study, reasons for exclusion, and subjects enrolled.

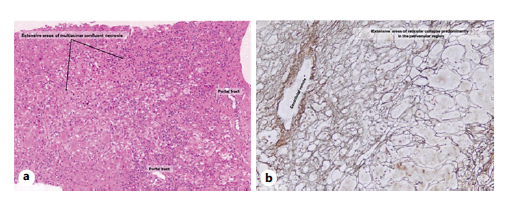

All cases with GAAIH had elevated levels of gammaglobulins. ANA were detected in 5 of the 6 cases, associated to SMA in 3 cases and with anti-Ro52 in 1 case. The only patient who did not exhibit ANA or SMA was positive for antibodies to soluble liver antigen/liver-pancreas and anti-Ro52. Concerning the histological findings in patients with GAAIH, we observed the presence of predominantly lobular lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate in all the cases, multiacinar necrosis in 3 cases, and confluent zone 3 necrosis in 2 cases (Fig. 2). A definitive and probable diagnosis of AIH according to the IAIHG score was observed in 2 and 4 patients with GAAIH, respectively.

Fig. 2 a,b Liver biopsy of a patient with GAAIH exhibiting confluent necrosis mainly in the centrilobular localization, sometimes with bridging, accompanied by lobular mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate. Presence of discrete portal predominantly lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory infiltrate. Absence of interface hepatitis or fibrosis.

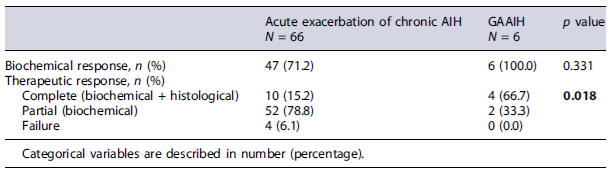

Comparative analysis between patients with GAAIH and acute presentation of chronic disease (Table 2) revealed a trend toward higher ALT levels in GAAIH (24.9 vs. 16.6 xULN; p = 0.057). There were no differences in AST, bilirubin, ALP, GGT, and gamma-globulin levels or ANA and SMA titers. Prothrombin activity (96.0 vs. 61.0%; p = 0.003) and albumin levels (3.95 ± 0.18 g/dL vs. 3.45 ± 0.53 g/dL; p < 0.001) were higher in patients with GAAIH. The IAIHG score was higher in patients with acute exacerbation of chronic AIH (18.5 vs. 16.5; p = 0.010). Sixty-six percent of patients with true GAAIH and 15.2% with acute exacerbations of chronic AIH experienced full treatment response (p = 0.018; Table 3).

After a mean follow-up of 9 ± 4.7 years, all 6 patients with GAAIH underwent a new biopsy; two of them had progressive liver disease, while the other four showed recovery and had little histological changes (reactional liver). During follow-up, 2 of these patients relapsed after discontinuation of treatment and 2 remained in clinical and biochemical remission to date. After reintroduction of immunosuppression, the 2 relapsed patients normalized aminotransferases and IgG levels and are in remission of the disease to date. During the follow-up, the survival in the group with GAAIH was 100%, while among the patients with acute exacerbation of chronic hepatitis, it was 42%.

Discussion

The diagnosis of acute presentation of AIH is challenging. Since the first report of acute AIH in 1984 by Lefkowich [24], some groups have been studying this condition. Still, many aspects, such as the correct diagnosis and prognosis of this particular form of presentation, remain unclear. The clinical spectrum of acute presentation is broad, ranging from asymptomatic conditions [24] to severe acute disease and fulminant hepatic failure [4-6].

Acute presentation of AIH is reported as infrequent, varying from 20% to 55% [4, 7, 25-28]. A difference in the frequency of acute-onset AIH may be due to differences in the population of patients and in the criteria used to define acute onset. Interestingly, the percentage of patients with acute presentation in our study (61%) was much higher than the cited references (20-55%). Comparing our data with those from Yamamoto, who used the same definition criteria as ours, our proportion of acute presentation was higher (61% vs. 38.5%)[7], perhaps due to ethnic differences. Certain ethnicities may be prone to developing a complicated AIH course [29, 30]. However, despite the high acute-onset AIH in this study, most patients exhibited histological characteristics of chronic disease, in agreement with other studies. Overall, we found a small number of patients with GAAIH, reflecting the rarity of this form of presentation of AIH.

Comparative analysis of the two groups showed higher levels of ALT in patients with GAAIH, a finding also described in other case series reported in the literature [3, 4, 12, 29, 31]. Patients with GAAIH often have low levels of gamma-globulins and IgG [3, 4, 8, 28] and absence or low titers of autoantibodies [4, 12]. Our study found no difference in gamma-globulin levels or ANA and SMA titers.

Our results showed higher levels of albumin and higher prothrombin activity in the group with GAAIH, in con-trast to the findings of Yamamoto et al. [7]. The explanation for this finding may be the fact that the present study has included only patients from an outpatient clinic, without having patients with fulminant or severe forms of acute presentation. These data suggest that genuine acute hepatitis is associated with fewer functional impacts due to a better hepatic residual liver function, except for fulminant liver failure patients. It has been reported in the literature that patients with acute severe autoimmune hepatitis may benefit from corticosteroids [32-34].

Five of 6 patients in this study had multiacinar or confluent zone 3 necrosis on liver biopsy and all had predominant lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates. The findings support the need for liver biopsy in cases with a clinical suspicion of autoimmune etiology if these histological characteristics are present.

We found predominantly lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates in all patients, even though we did not find all classical histological characteristics of AIH in our cases. This finding, along with the observation of positive autoantibodies and elevated gamma-globulin levels, resulted in IAIHG scores compatible with definite (2 cases) and probable (4 cases) AIH. These results show that, although higher in patients with acute exacerbation of chronic AIH, this score is helpful forthediagnosisofpatientswithGAAIH.

Four out of the 6 patients with GAAIH had a complete response to treatment (biochemical plus histological). However, total bilirubin levels were above 10 mg/dL on presentation in 3 of the 5 patients of this group (data not shown), a poor prognostic factor of response to treatment [4]. These results may suggest that the degree of functional reserve has a positive impact on the therapeutic response. Insignificant fibrosis has previously been related to bio-chemical response to treatment [29]. The fact that none of

the patients presented prothrombin activity <40% (data not shown), a factor related to poor prognosis [7], may have contributed to the good clinical response observed in this study. Nonetheless, liver dysfunction has been reported as a predictor of biochemical response to treatment [29]; a study with fewer patients evidenced no difference regarding treatment failure and clinical presentation [26]. At long-term follow-up, 2 patients presented progressive liver disease with classical AIH periportal activity, as seen in other studies [11, 15].

There are some possible limitations to the present study. Although the total number of patients included in the study was representative of the overall population, we examined feasible associations between certain factors and GAAIH, noticeably reducing the number of subjects presenting particular variable combinations and, consequently, the power of statistical tests. Although it is not a strict rule, maintaining a minimum of ten events per variable is advised for logistic regression analysis. This recommendation is based on studies that showed increasing bias and variability, unreliable coverage of confidence intervals, and problems with model convergence as the events per variable declined below ten [35-37]. Another limitation of this study is its retrospective design, which was minimized by using a standardized protocol and the absence of severe or fulminant cases.

In summary, this study showed that acute biochemical presentation of AIH was frequent (61%), while GAAIH was uncommon (8.3%). The autoimmune etiology of acute hepatitis should, therefore, always be considered. The IAIHG score contributes to the diagnosis. A biopsy should be performed whenever possible, as it is very useful for identifying these cases, permitting the early institution of treatment before a significant functional loss occurs and thus improving the prognosis of these patients. Patients with GAAIH had a better complete therapeutic response, suggesting a more preserved liver function at presentation, and early diagnosis has a positive therapeutic implication.