Introduction

Chronic hepatitis delta is the most aggressive form of viral hepatitis [1-3]. Although universal testing of patients with positive hepatitis B virus (HBV) surface antigen has been proposed by European recommendations for more than 10 years [4], diagnosis can sometimes be hindered by laboratorial shortcomings, especially when considering less frequent genotypes [5].

The association of hepatitis delta virus (HDV) infection with positive autoantibodies and autoimmune features has been known for decades [6, 7]. However, to date, very few cases of clinical autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) have been reported in association with HDV infection, most of them being in the context of treatment with peginterferon [8, 9]. In this clinical case study, we describe the challenges faced in the diagnosis and treatment of a patient with autoimmune hepatitis that we believe was induced by HDV.

Case Report

The case refers to a 46-year-old woman born in Guinea-Bissau, where she worked as a teacher. Her past medical history was positive for hypertension, treated with losartan 50 mg since 2016, and a cholecystectomy. The patient moved to Portugal in 2018 to investigate complaints of diffuse nonspecific abdominal discomfort and nausea with 2-month duration. She denied alcohol intake or exposure to hepatotoxic drugs. She had no known family history of liver disease, viral infections, or cancer.

Physical examination was unremarkable. The patient’s weight was 45 kg and height was 1.60 m, corresponding to a body mass index of 17.5 kg/m2. Initial blood work-up showed elevated liver enzymes, namely, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 540, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 686, alkaline phosphatase 111, and gamma-glutamyl transferase 198 U/L, with INR 1.2 and normal bilirubin and platelet count. Abdominal ultrasound revealed a normal liver, slight main biliary duct dilatation due to previous cholecystectomy, and no splenomegaly, ascites, or venous thrombosis. She was admitted in the Internal Medicine Department for investigation. Further testing showed positive HBsAg, HBcAb, and HBeAb, with negative HBeAg and HBsAb and undetectable HBV DNA. Total anti-HDV was positive, with negative IgM and undetectable RNA. Other hepatotropic viruses were excluded, with negative anti-hepatitis C virus (HCV), anti-hepatitis E virus IgG and IgM, and anti-human immunodeficiency virus; positive anti-hepatitis A virus IgG with negative IgM; positive anti-CMV (cytomegalovirus) IgG with negative IgM; positive Epstein-Barr virus VCA IgG and IgM and EBNA IgG, with negative DNA. Rickettsia, Coxiella, and Plasmodium falciparum were also excluded. The patient had mild peripheral eosinophilia and a positive

IgG antibody for Strongyloides stercoralis (12.59 [<1.00]), which was also identified in stool. Autoimmune panel was positive for antinuclear antibodies (ANA), fine-speckled, and with a titer of 1/ 320, but negative for anti-smooth muscle, anti-liver kidney micro-somal type 1 (anti-LKM1), anti-liver cytosol type 1 (anti-LC1), and anti-soluble liver antigen (anti-SLA) antibodies, as well as anti-mitochondrial antibodies. Serum protein electrophoresis showed a polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia. Serum immunoglobulin G (IgG) was elevated at 2,570 mg/dL, while immunoglobulin M was normal. Alpha-1 antitrypsin, ceruloplasmin, urinary copper, serum iron, and serum ferritin levels were within normal range.

The patient was treated with ivermectin for Strongyloides stercoralis infection. Following treatment, the eosinophilia resolved in 4 days, and repeat stool testing was negative for parasites. There was a decrease in transaminases (AST 100, ALT 141 U/L), and the patient was discharged.

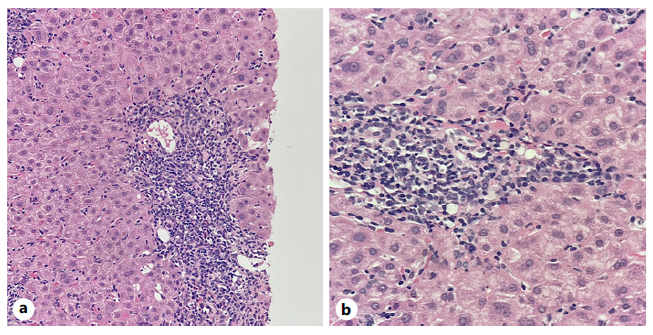

Around 6 months later, the patient was readmitted due to persistent abdominal discomfort. At this time, she presented AST 323, ALT 331 U/L, and IgG 3,101 mg/dL. After Hepatology consultation, a liver biopsy was performed, showing intense lymphoplasmocytic infiltrates, interface hepatitis, emperipolesis, and no cytopathic viral effect, as shown in Figure 1a, b. These findings were compatible with autoimmune hepatitis with mild fibrosis (Ishak fibrosis score 1/6).

Fig. 1 Portal tracts showing intense inflammatory infiltrates with lymphocytic predominance, rich in plasmocytes and with rare eosinophils, with interface hepatitis and hepatocyte ballooning. a H&E ×200. b H&E ×400.

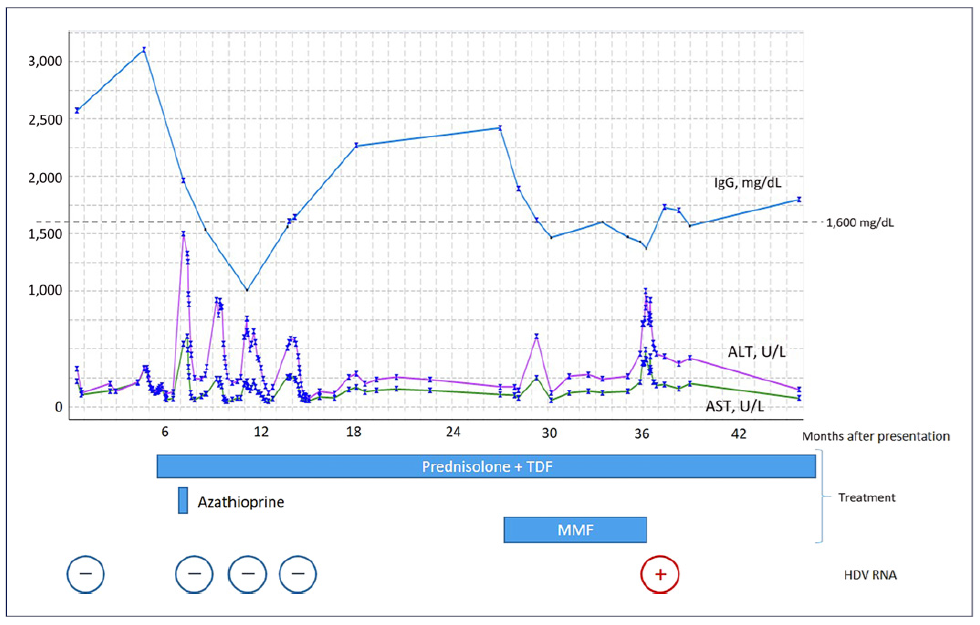

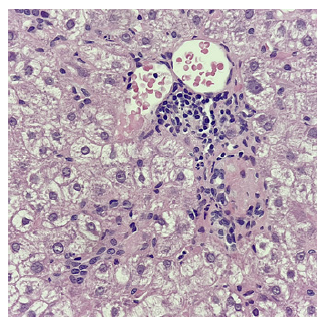

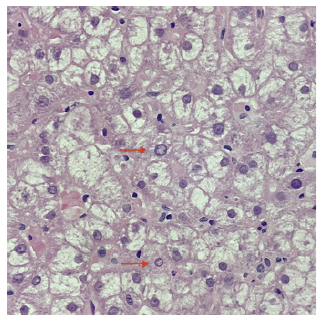

When applying the revised original AIH diagnostic score, the diagnosis was classified as probable (13 points, pretreatment) [10]. Therefore, the patient was started on prednisolone 1 mg/kg/day while commencing prophylactic tenofovir disoproxil fumarate. Transaminases had spontaneously decreased in the previous 4 weeks (AST 152, ALT 181 U/L) and had a further reduction after 7 days of therapy (AST 59, ALT 108 U/L). Upon azathioprine (AZT) 50 mg introduction 2 weeks later, however, there was again a steep rise in transaminases (AST 544 and ALT 1496 U/L), with IgG reduction to 1,962 mg/dL (Fig. 2). AZT was stopped due to presumed toxicity, and PDN was increased to 1 mg/kg/day. A second liver biopsy showed less pronounced inflammatory infiltrates and features suggesting possible viral superinfection (shown in Fig. 3, 4). An extensive viral search was again conducted, including negative HBV and HDV viral loads, positive Epstein-Barr virus DNA in serum (556 copies/mL) but negative in liver tissue, and positive herpes simplex IgM. After discussing with the Infectious Diseases team, the patient was treated with acyclovir for 21 days, and steroids were tapered, resulting in a decrease in transaminases.

Fig. 2 Graphic showing the evolution of transaminases and immunoglobulin G (IgG) throughout time and the moment of introduction of different treatments. Broadly speaking, there is an inverse correlation between transaminases and IgG levels. ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; HDV, hepatitis delta virus; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; TDF, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate.

Fig. 3 Portal tract with mild-to-moderate inflammatory infiltrates with lymphocytic predominance and rare plasmocytes (H&E ×400).

Fig. 4 Hepatocytes showing nuclei with peripheral condensation of chromatin (arrows) and hyaline and amorphous cytoplasm suggesting viral cytopathic effect, in a background of intralobular inflammatory activity (H&E ×400).

She was kept on low-dose PDN (7.5 mg) for several months, maintaining a normal IgG and transaminases around 2-3 times the upper limit of normal. However, there was a new disease flare (AST 166, ALT 286 U/L, IgG 2,417 mg/dL), with repeated negative viral screening and histology revealing only features of AIH. Therefore, PDN was increased to 20 mg and mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) 1.5 g/day was added, with no response in transaminases.

About 6 months later, despite normalization of IgG, transaminases peaked again (AST 490, ALT 1,000 U/L). HBV DNA and HDV IgM remained negative. Serum hepatitis E RNA was also negative. Histology showed active AIH, including moderate lymphoplasmocytic infiltrates, interface hepatitis, and emperipolesis, with no cytopathic viral effect. Surprisingly, HDV viral load, which had been repeatedly undetectable in the past, now came back positive at 103,100 UI/mL. Further testing in an external laboratory classified the virus as genotype 5 (GT5).

Having diagnosed chronic hepatitis delta, MMF was stopped. Therapy with pegylated interferon was contraindicated due to the autoimmune disease. More recently, almost 1 year later, bulevirtide became available in our country. However, the patient refused this treatment for personal reasons because she is currently spending most of her time in her home country, Guinea-Bissau, where she has both her family and her job. She is being kept on steroid monotherapy (prednisolone 20 mg), with persisting hepatitis (AST 127 and ALT 350 U/L). There were concerns about progression of fibrosis, as platelet count has progressively dropped to 78,000 × 109/L. However, her liver stiffness (FibroScan®) value is currently at 9.0 kPa.

Discussion

This is a complex and challenging case of chronic hepatitis delta presenting with autoimmune features. It is our belief that HDV acted as a trigger for autoimmunity in our patient. In fact, viral infections have long been described as possible triggers of autoimmune liver diseases in genetically predisposed individuals. One of the few known autoantigens in AIH, specifically AIH type 2, is CYP2D6, which shares an amino acid sequence with HCV proteins and is the target of anti-LKM1 autoantibodies, suggesting molecular mimicry [11]. In fact, 10% of patients infected with HCV present detectable anti-LKM1 antibodies [12]. Auto-antibodies associated with AIH are also common in HBV infection, particularly in HBV/HDV patients [7] (with up to two-thirds of patients presenting ANA, anti-smooth muscle, or anti-LKM3) [13]. Although these are generally considered part of the course of the viral infection [14], cases of concurrent HBV and AIH have been described, with viral infection preceding AIH by many years and possibly having worked as a trigger [8]. Furthermore, occult HBV infection has been described in higher proportions of AIH patients when compared to the general population [15-17], suggesting an etiologic role for HBV in AIH. Regarding HDV specifically, very few cases have been described in associ-ation with AIH, most of them being during or after treat-ment with interferon-alpha-based regimens [8, 9].

Establishing the diagnosis of AIH in the context of concomitant viral hepatitis is challenging and controversial. In fact, diagnostic scoring systems deduct points when there is evidence of viral hepatitis [10, 18] and are therefore not adequate in this setting [8]. In the case of our patient, all the classical hallmarks of autoimmune hepatitis were in fact present. It could be argued, though, that if HDV cure led to reversal of autoimmunity, then the disease would not be self-perpetuating and would therefore be fundamentally distinct from classical, or “idiopathic,” AIH. A similar rationale has recently been used to propose the designation of “drug-induced autoimmune-like hepatitis” to liver disease with laboratory and histological features that may be indistiguishable from AIH but that resolve upon removal of the trigger (in this case, a drug), therefore not requiring long-term immunosuppression [19]. Similarly, in our patient, “autoimmune-like hepatitis” could potentially be used to describe the autoimmune liver features. Very recently, a case report was published where bulevirtide was used to treat chronic hepatitis delta in a patient with autoimmune hepatitis. Differently from our patient, this patient had cirrhosis with portal hypertension and was negative for ANA. Following viral suppression, IgG normalized, and there was regression of autoimmune features on histology [20].

In the case of our patient, the diagnosis of HDV required a very high index of suspicion. This was driven by factors such as the dissociation between transaminases and IgG, a somehow erratic response to immunosuppressive treatment and ALT being always above AST (Fig. 2), as well as the patient’s origin (Western Africa, endemic for HBV/HDV) [21].

It is not clear though why the HDV viral load was only positive at the fourth determination. The method for extraction (MagNA Pure®, Roche) and amplification (RealStar® HDV RT-PCR, Altona Diagnostics) did not change throughout time. Automated extraction methods, including the one used in this case, were shown to underestimate HDV RNA by about 10-fold when compared to a manual method [22]. As an alternative to serum HDV RNA, HDV antigen search in liver biopsy by immunohistochemistry could have been performed. In fact, this request was placed but then canceled, as serum HDV RNA came back positive in the meantime.

It is possible that the RNA PCR test that was used could only detect the virus when it reached a certain threshold. This leads to the question of whether immunosuppression could have unveiled a chronic HDV infection. It is possible that the peak in transaminases that followed AZT’s introduction was actually an undetected HDV flare rather than hepatotoxicity. In addition, it was only months after the introduction of MMF, with IgG being in the normal range and probably the patient being most immunosuppressed, that HDV was finally detected (Fig. 2). Differently from HBV monoinfection, there is a paucity of data regarding reactivation of HDV in the context of immunosuppression, with only case reports mentioning HDV flairs in patients treated with sunitinib [23] and chemotherapy for lymphoma [24].

Another key aspect of this case is the fact that the patient was infected with HDV GT5, which probably hindered the diagnosis. In fact, most laboratories underestimate or fail to detect GT5 and other African genotypes [5]. Furthermore, when compared to GT1, patients infected with GT5 were shown to less frequently express IgM antibodies [25] (such was the case of our patient, who was persistently negative for anti-HDV IgM). The issue of HDV genotype is of crucial importance in our center since the majority of our HDV patients come from Guinea-Bissau and are infected with GT5 [26]. This subject has become increasingly relevant in Europe in recent years as domestic infection, mostly related to intravenous drug use, are being replaced by cases introduced by immigration from endemic areas [3]. Also, the difficulties that we faced in bringing our patient to clinic and starting treatment are in line with reports from the French cohort, where migrant populations were shown to have suboptimal adherence and commit-ment to care, driven by socioeconomic insecurity [27].

In conclusion, we present a challenging case of auto-immune or “autoimmune-like” hepatitis, probably induced by chronic HDV infection. High suspicion of HDV was essential because, had the case been interpreted as refractory AIH, with escalation of immunosuppres-sion, a more severe course of the viral infection might have ensued. Recently, HDV suppression with bulevirtide was shown to reverse autoimmune liver disease. We hypothesize that the same could have happened to our patient, had she accepted this treatment.