Introduction

Gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors (NET) arise from diffuse neuroendocrine system and account for only 0.5% of all malignancies and 2% of gastrointestinal malignancies. Gastric NETs (GNETs) are the most frequent of all digestive NETs, representing up to 23% of the cases ENT#91;1, 2ENT#93;. The incidence and prevalence have been increasing, probably due to the wide spread use of endoscopic and radiological examinations and increased recognition by pathologists. Thus, GNETs are now often found by chance during endoscopy that was done for another reason.

In 2019, the World Health Organization (WHO) categorized these neoplasms as grade 1-3NET,neuro-endocrine carcinoma (NEC), and mixed neuroendocrine-nonneuroendocrine neoplasm based on histological classification, Ki-67 index, and mitotic activity ENT#91;3ENT#93;. Formal TNM staging classifications have been introduced for gastrointestinal NETs by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC), and the European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society (ENETS). In addition to grade and TNM, GNETs should be further subclassified into 4 subtypes according to clinicopathological characteristics since this classification has management implications. GNETs arising in the context of hypergastrinemia are classified into type I if associated with corpus atrophic gastritis/autoimmune gastritis and type II if associated with non-compensatory hypergastrinemia (produced by a gastrinoma) and Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. Types III and IV are considered sporadic, not being associated with hypergastrinemia nor any back-ground pathology. They are distinguished by histological grade, with type IV being grade 3 (mitotic index >20% and Ki-67% >20%) ENT#91;4ENT#93;. This classification is useful in predicting prognosis as well as in therapeutic decision-making.

Despite the increasing incidence of these types of lesions, it is not yet certain which factors are predictors of worse prognosis and whether these should alter the therapeutic strategy. Moreover, with the current use of advanced endoscopic techniques, these now play a role in the treatment of these patients, particularly in patients with type I GNET. However, evidence regarding the different therapeutic strategies in these patients is limited and optimal management is still not well established. The strategy adopted depends on the preference and experience of the endoscopist, while others propose a size threshold for endoscopic resection.

The aim of the study was to analyze the clinical and pathological characteristics of GNETs, identify prognostic factors associated with overall survival and metastasis, specifically in type I NETs, and evaluate the impact of serial measurements of chromogranin A (CgA) in these patients. We also assessed the clinical outcomes of patients with type I GNET treated with different strategies (polypectomy/surveillance, mucosectomy ENT#91;EMRENT#93;, endoscopic submucosal dissection ENT#91;ESDENT#93;, surgery, and somatostatin analogues).

Materials and Methods

Patients and Methods

A retrospective cohort study was performed. The Pathological database of the Portuguese Oncology Institute of Porto was searched for GNETs diagnosed between January 2010 and December 2019 and consecutive patients were included. Patients with less than 12 months of follow-up and patients submitted to surgery for gastric adenocarcinoma were excluded.

Data collection was performed through analysis of electronic medical records and patient charts. Patient demographic characteristics were collected along with the following clinical, surgical, and pathological characteristics: sex, age, presence of symptoms at diagnosis, chronic use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) (>2 years), hemoglobin, vitamin B12, gastrin and CgA levels at diagnosis, presence of antiparietal cell and anti-intrinsic factor antibody, number and size of lesions, histological characteristics of the biopsy or the specimen (Ki-67 index and mitotic activity, sub-mucosal invasion, lymphovascular infiltration and perineural permeation, resection margins), presence of gastric premalignant conditions (atrophy and intestinal metaplasia ENT#91;IMENT#93;) in the antrum and body of the stomach, NET type, treatment, local and meta-static recurrence, metastasis, and overall survival.

At our center, there is a multidisciplinary meeting where the most complex patients are discussed. Endoscopies were performed by 6 experienced endoscopists who perform >500 endoscopies/year.

This study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Portuguese Oncology Institute of Porto in 2020 (CES 44/021). Patients signed informed consent for the endoscopic procedures.

Definitions

En bloc resection was defined as the removal of a lesion in a single piece regardless of the depth of invasion and lymphovascular invasion. Complete resection (R0) was defined as end bloc resection with no involvement of the lateral and vertical margins, and no lymphovascular invasion.

Local recurrence referred to the recurrence of tumor at the previous endoscopic resection site, and synchronous lesions was defined as the recurrence of tumor at a different site in the stomach within 1 year of the initial endoscopic resection. Metachronous recurrence was defined as tumor detected more than 1 year later, distant from the site of initial resection. The follow-up period was defined as the interval from the initial diagnosis of gastric NETs to the last outpatient clinic visit.

The Ki-67 proliferation index is a scoring system that measures proliferation and growth of cells. A Ki-67 index of 3% or lower means that fewer than 3 in every 100 cells (3%) are dividing - grade 1 NET (NET G1). Ki-67 index of more than 20% corresponds to a grade 3 ENT#91;3ENT#93;. Serial measurements of CgA (at least 3 measurements during the follow-up) were performed and an elevation of 200 ng/mL above a baseline value was considered as increased.

Management on Type I GNETs

The endoscopic characteristics were examined during esophagogastroduodenoscopy, focusing on the size, number, morphology, and location of the lesions. A simultaneous assessment of the gastric mucosa was performed and biopsies of antrum and corpus were regularly taken according to the modified Sydney-Houston protocol. Depending on the characteristics found and factors such as the presence of metastases, different strategies were carried out and patients were divided into 5 groups: surveillance/polypectomy, endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR), ESD, surgery, and somatostatin analogues.

The surveillance/polypectomy group included patients diagnosed through biopsy who had no lesions removed during endoscopic follow-up and patients who had one or more polyps removed by polypectomy with biopsy forceps or cold snare (lesions <5-10 mm) and no other strategy was performed.

Beyond this size, the definitive choice for selecting the type of endoscopic resection was made mainly by the endoscopist (EMR vs. ESD) taking into account lesion size, morphology, and endosonographic/radiological findings. The surgery group includes patients undergoing atypical gastrectomy, subtotal gastrectomy, or antrectomy. Subtotal/atypical gastrectomy was per-formed in patients with larger lesions (not amenable to endoscopic resection) or with the presence of concomitant lymph node metastasis. Antrectomy was selected only in 1 patient with type I GNET who had multiple lesions as a way to reduce the acid-producing stimulus. Somatostatin analogues were the therapy of choice for patients with type I GNET with multiple lesions (>10) or in the presence of metastases.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS version 26. Data are presented as the number and percentages for categorical variables. Continuous variables are presented as mean and standard deviation or as median and interquartile range (IQR)

(Q25-Q75). Univariable analysis was performed using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test, while continuous variables were compared using Student’s t test or Mann-Whitney test if nonparametric data.

Multivariable model included variables with p < 0.2 in the uni-variable analysis. A p value <0.005 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patients

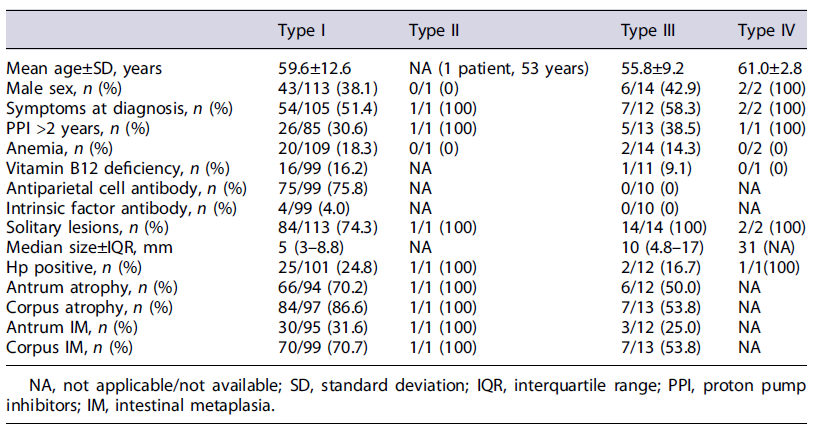

A total of 137 patients with GNET were identified in the Pathological database, of which 4 patients submitted to surgery due to carcinoma with the presence of GNET on the surgical specimen and 1 patient with less than 1 year of follow-up were excluded. We included 132 patients with GNET (type I, 113 patients; type II, 1 patient; type III, 14 patients; type IV, 2 patients; not classifiable, 2 patients), with 61% being female (n = 80) and a mean age at the diagnosis of 65.5 years (±12.2) (Table 1). Two patients were not classified since no data were available in these patients on serum gastrin, anti-parietal cell, or intrinsic factor antibodies or histology of the gastric mucosa.

At diagnosis, 52% of patients had symptoms (36 patients had dyspeptic symptoms, 18 abdominal pain, 14 symptoms related to gastroesophageal reflux and 1 diarrhea), 18% anemia, and 15% vitamin B12 deficiency. The median gastrin value was 689 pg/mL (IQR 184-1,141) and CgA 186 ng/mL (100-288). One-third of the patients (33/99) had used PPIs for more than 2 years. Antiparietal cell antibody and intrinsic factor assays were performed in 109 patients and were positive in 75 and 4 patients, respectively.

Most lesions were solitary (79%, n = 104), with a median size of 5 mm (IQR 3-10). Thirty-five patients had a lesion larger than 10 mm. In the evaluation of gastric mucosa, 68.5% and 83.0% had atrophy of the antrum and atrophy of the body, respectively. IM of the antrum and body was present in 32.1% and 69.3%, respectively. Hp was present in 29 patients (25%).

Prognostic Factors

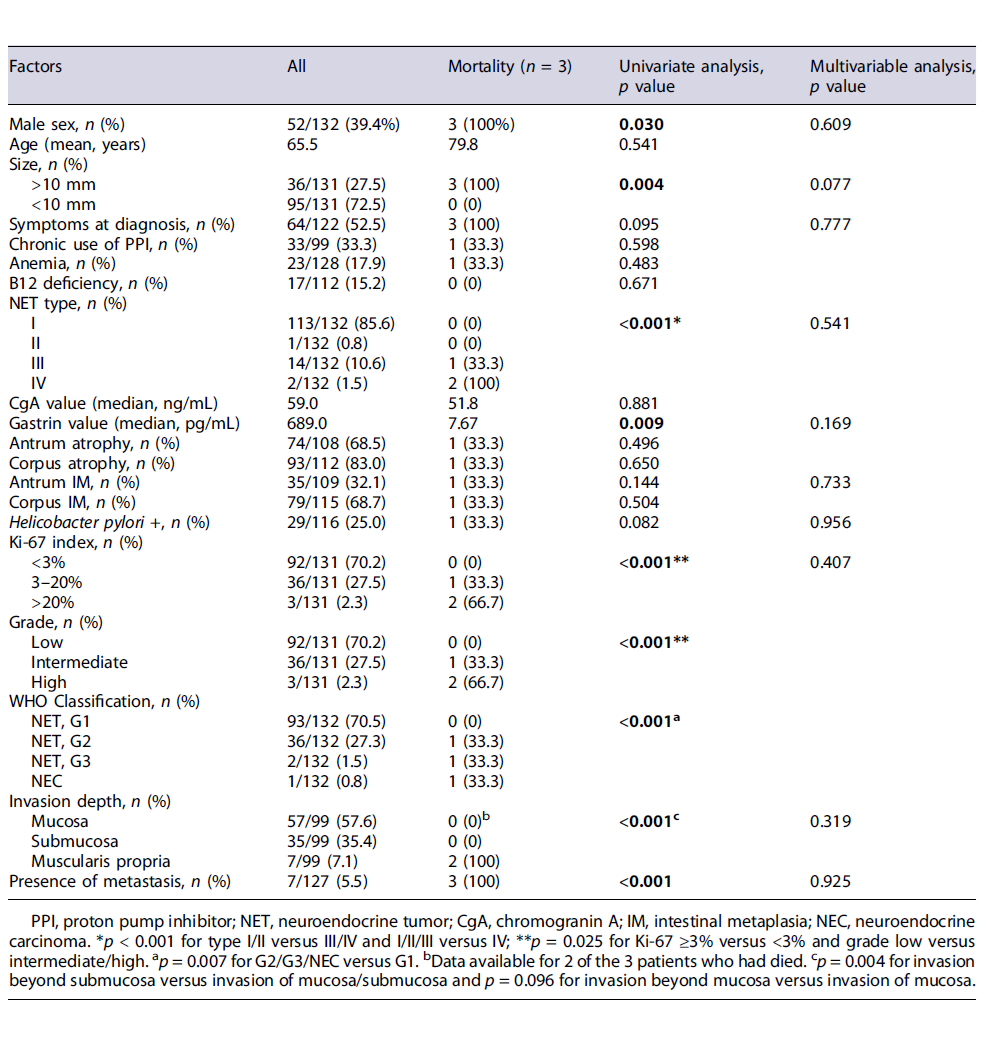

During the follow-up period (median 66 months), 3 patients died due to metastatic disease (1 patient with type III GNET and 2 patients with type IV GNET) and there were no deaths due to other causes. Overall, disease-specific survival was 100% for type I and type II gastric NETs, 92.9% for type III, and 0% for type IV (mean follow-up 69 months).

Male gender (p = 0.030), lesion size >10 mm (p = 0.004), type III/IV versus I/II (p < 0.001), Ki-67 ≥3%versus <3% (p = 0.025), intermediate/high grade versus low grade (p = 0.025), WHO Classification G2 or more versus G1 (p = 0.007), invasion beyond the submucosa (p < 0.001), and presence of metastases (p < 0.001) were identified as risk factors for mortality (Table 2). Age, anemia, vitamin B12 deficit, chronic use of PPIs, and presence of gastric premalignant conditions were not related to mortality. Multivariate analysis did not identify any independent factors for mortality.

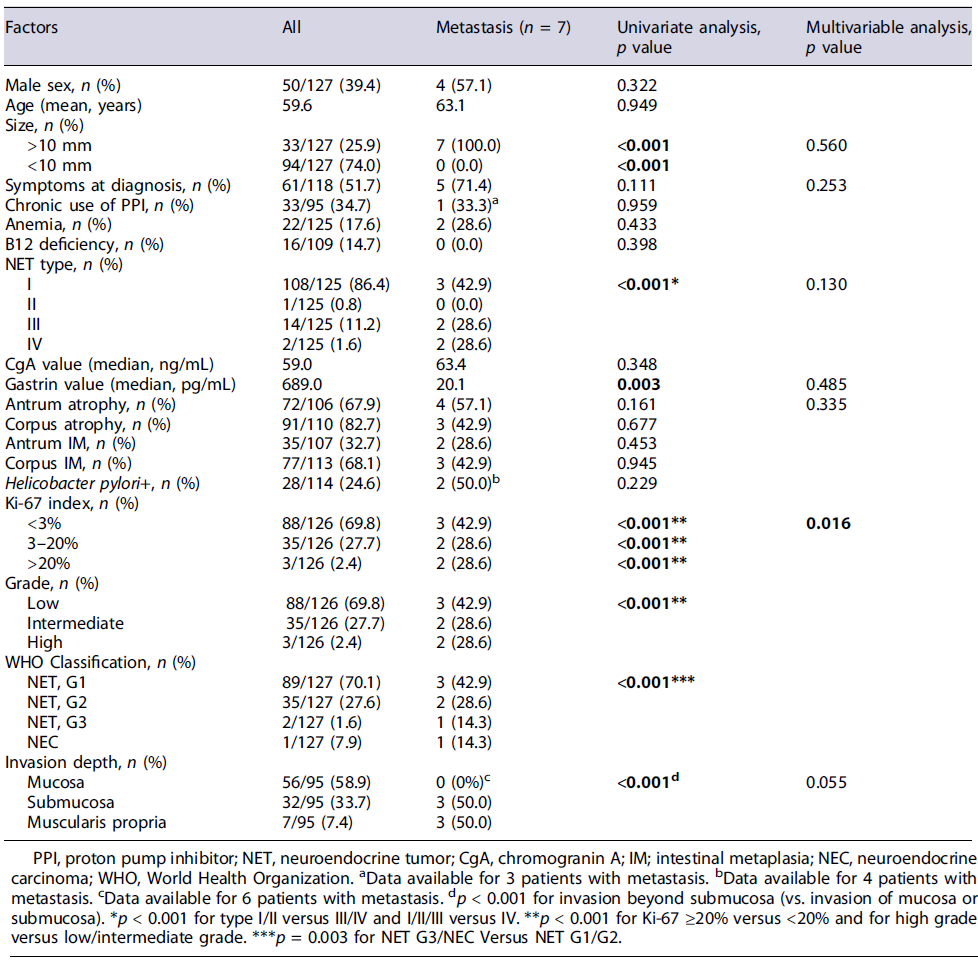

Seven patients presented metastatic disease, 4 at diagnosis and 3 during follow-up (5.3%, 3 patients with type I GNET, 2 patients type III, and 2 with type IV), diagnosed with Gallium-68-Dota-NOC-PET. Four patients presented distant metastases and 3 lymphatic metastases. The most common distant metastatic site was the liver (n = 4), followed by bone (n = 2) and peritoneum (n = 1).

Lesion size >10 mm (p = 0.001), Ki-67 > 20% (p < 0.001), high grade (p < 0.001), NET G3/NEC (p = 0.003), invasion beyond submucosa (p < 0.001), and lower gastrin value (p = 0.003) were associated with metastasis on univariate analysis. Multivariable analysis revealed that Ki-67 >20% (p = 0.016) was an independent risk factor for metastasis (Table 3). In our cohort, patients with type I and III GNETs, <10 mm, and confined to the mucosa did not develop metastasis or died due to GNET.

Evaluation of Chromogranin A

Serial measurements of CgA were performed in 73 patients. Overall, CgA showed a sensitivity for detection of recurrence (recurrence of disease requiring a change in therapeutic strategy) of 20% and a specificity of 79%. In type I GNET patients, CgA demonstrated a sensitivity of 8% and a specificity of 71%.

Management of Patients with Type I GNET Overall, 113 patients with type I GNET were included, 62% were women, with a mean age of 60 years. At diagnosis, 18% of patients had anemia and 16% vitamin B12 deficiency.

In the evaluation of gastric mucosa, 70% and 87% had atrophy of the antrum and atrophy of the body, respectively. IM of the antrum and body was present in 32% and 71%, respectively. Hp was present in 25 patients (24.8%). Antiparietal cell and intrinsic factor antibodies were present in 76% and 4% of patients with autoimmune gastritis, respectively.

At diagnosis, the surveillance/polypectomy strategy was adopted in 77 patients. Twenty-four patients under-went EMR, 6 underwent ESD, 3 underwent surgery (2 for evidence of lymph node metastases), and 3 started somatostatin analogues.

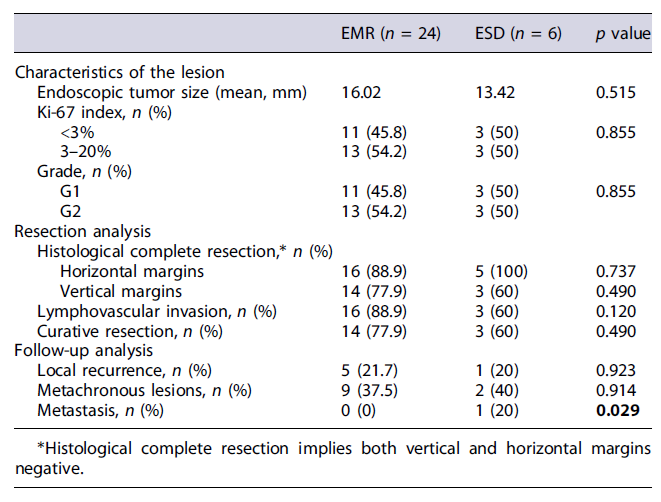

Patients undergoing EMR and ESD had no statistically significant differences in maximum lesion diameter (16 vs. 13 mm, p =0.515),Ki-67index (p = 0.745), and grade (p = 0.855). The rate of complete histological resection (78 vs. 60%, p = 0.255) and the presence of negative horizontal and vertical margins (89 vs. 100%, p = 0.597; 77 vs. 60%, p =0.470, respectively) were similar in both groups. The presence of positive horizontal or vertical margins had no impact on the development of metastases during the follow-up (p = 0.917 and p = 0.790, respectively) (Table 4).

Lesions removed by ESD had more frequently lymphovascular invasion, without significant difference (40 vs. 6%, p = 0.120). All patients had at least one surveillance endoscopy. The development of metachronous lesions and local recurrence was similar in EMR and ESD groups (38 vs. 40%, p = 0.914 and 22 vs. 20%, p = 0.932, respectively). In the ESD group, 1 patient developed lymph node metastasis (p = 0.029) during surveillance - a patient with a type I GNET, with 12 mm (Ki-67 3-20%, G2) with vertical and lympho-vascular invasion on the endoscopic dissection specimen.

Three patients were submitted to surgery. One of the patients had multiple lesions and underwent antrectomy in 2010 to reduce hypergastrinemia. The other 2 patients underwent subtotal gastrectomy since at diagnosis they presented lesions 16 and 26 mm in size with lymph node metastasis on preoperative CT. Three patients started somatostatin analogues since they had multiple gastric lesions that were considered not amenable to surveillance/endoscopic resection.

Management of Patients with Type III/IV Gastric NETs Overall, 14 patients were treated for type III GNET in our center: 5 underwent polypectomy at diagnostic endoscopy (lesions <10 mm), 5 underwent EMR, 1 under-went ESD, and 3 underwent surgery. In the group of patients submitted to polypectomy, there was no local recurrence or evidence of metastases during the follow-up. The complete resection rate after EMR was 40% and 1 patient developed lymph node metastasis (20% of the patients submitted to EMR). In 1 patient, ESD was curative and without local or distant recurrence during a follow-up of 10.6 years. Also, surgery was curative for the 3 patients, but 1 patient developed liver metastasis and died during follow-up. Of the 2 patients with type IV GNET, 1 underwent surgery and chemotherapy after the diagnosis of metastatic disease and the other started chemotherapy at diagnosis.

Discussion

The incidence of GNETs has increased over the past few decades and type I GNETs represent 70-80% ENT#91;5ENT#93;. In our study, type I GNETs accounted for 86% of the patients, type III, 11%, type IV, 2%, and only 1 patient had type II. The lack of a standard staging system for GNETs substantially hinders the prediction of the risk of recurrence and prognosis of patients suffering from GNETs. The AJCC, ENETS, and WHO staging classifications provide a better stratification of gastric NETs and they are routinely employed ENT#91;3, 6ENT#93;. Our retrospective cohort with a long follow-up confirms that type I GNETs have an excellent prognosis, and that endoscopic resection is effective and safe for the treatment of type I and small type III gastric NETs (selected lesions in the latter). We also identified risk factors for metastasis and mortality that should dictate a more intensive surveillance in these cases. Our findings of low sensitivity and specificity of sequential CgA for tumor recurrence show that it is not useful neither as diagnostic nor as tumor biomarker for surveillance of these patients.

Most GNETs are diagnosed incidentally during screening endoscopy and classifying them is crucial in deciding the proper treatment as they can be either indolent or aggressive. In our study, as expected, we found type of GNET as a prognostic factor, with no deaths in the group of patients with type I GNET, even though 3 patients presented lymph node metastasis. Type III and IV GNETs have a more malignant biological behavior with a metastasis rate in our study of 8.7 and 100%, which was different to that reported in the literature (40%), probably due to the low number of patients ENT#91;7, 8ENT#93;.

In our cohort, we found male sex as a mortality predictor, which is in line with previous studies ENT#91;9, 10ENT#93;. The protective effect of female gender observed in various studies is still unclear.

All patients with metastases or who died during the follow-up period had lesions larger than 10 mm in size. In a Korean study, a tumor size was significantly associated with survival and a tumor size of ≥2 cm was a risk factor for metastasis ENT#91;11ENT#93;. We also demonstrated that patients with Ki-67 >20%, an intermediate/high grade (vs. low), and invasion beyond submucosa had a poor prognosis, with a high risk of metastasis and mortality. According to Nadler et al. ENT#91;12ENT#93;, Ki-67 is a very reliable marker for NETs when used to stage tumors with ENETS and WHO staging methods. GNETs with poor differentiation (G3) are more aggressive tumors and have poorer prognosis than well-differentiated (G1-G2) ENT#91;13ENT#93;. Tian et al.ENT#91;14ENT#93; found a 5-year survival of patients with well-differentiated tumors of 80.4%, which was nearly 4 times the overall survival of patients with G3 tumors. In our study, there was only 1 patient with NEC and two with G3 lesions, and the mortality was 100 and 50%, respectively. In multivariate analysis, we did not identify any independent factor for mortality probably due to the low number of deaths (n = 3). For metastasis, Ki-67 was identified as an independent risk factor. According to our results, patients with prognostic factors such as lesions >10 mm, Ki-67 >20%, intermediate/high grade, and invasion beyond the submucosa should be monitored with PET-DOTANOC initially every 6 months and after 2 years annually.

According to ENETS guidelines, published in 2016, GNETs should be treated according to their classification and size. Type I and II small tumors should be monitored or treated with minimal endoscopic or laparoscopic surgery and type III tumors require radical gastrectomy.

However, some studies showed that endoscopic resection is possible for larger lesions (>10 mm) and even for smaller type III GNETs ENT#91;15-17ENT#93;.

In our cohort, we had 113 patients with type I GNET. The strategy adopted depended on the characteristics of the lesions (morphology and size), but also on endoscopist experience and preferences. In a recent study by Chin et al. ENT#91;18ENT#93;, the rate of disease progression during surveillance was 29.5%, suggesting that simple surveillance may not be safe in these patients. However, Esposito et al. ENT#91;15ENT#93; demonstrated that a noninterventional approach might be justified for small lesions (<5 mm), since none of the patients underwent disease progression after a median follow-up of almost 4 years. Also, the authors agree that endoscopic resection remains the preferred approach for larger tumors, owing the risk of disease progression, although low, as suggested by European guidelines ENT#91;19ENT#93;. There are a few studies with a limited number of patients comparing endoscopic resection by EMR and ESD for type I GNETs. A retrospective study (n = 87) has compared both techniques for <10 mm lesions and ESD showed a trend to a better pathologically complete resection rate (95% vs. 83%, p = 0.17) and a trend to a higher adverse event rate (perforation 2.6% vs. 0%, delayed bleeding 5.1% vs. 4.2%), but with no statistically significant differences ENT#91;20ENT#93;. Sato et al. ENT#91;16ENT#93; analyzed 13 patients and showed a better complete resection with ESD versus conventional EMR. In our study, the characteristics of the lesions submitted to ESD and EMR were comparable and the rate of complete histological resection was similar in both groups (78 vs. 60%), but lympho-vascular invasion was more frequent in the ESD group (40 vs. 6%). Besides, the recurrence rate was also similar in both groups. Of note, the presence of positive vertical or horizontal margins after EMR or ESD had no impact on prognosis. There is no evidence of clear superiority of one technique over another, and the choice of technique should take into account not only size but also morphology and lifting, and the technique with a high likelihood of en bloc/R0 resection should be chosen. For type III GNETs, ENETs recommend surgery and endoscopic resection is still not debated ENT#91;6ENT#93;. However, there is now evidence to support endoscopic resection. Kwon et al. ENT#91;17ENT#93; analyzed 50 patients with type III GNETs treated with endoscopic resection (EMR in 41 and ESD in 9 cases). Pathological incomplete resection was observed in 10 cases (no differences between the two techniques), and during the follow-up period (43 months), there was no evidence of tumor recurrence). In our cohort, polypectomy was performed in 5 patients at diagnosis because these lesions were small (5-10 mm) and were not suspected to be NETs. Endoscopic resection was performed in 6 patients (5 EMR and 1 ESD). A complete resection rate after EMR was 40% and 100% after ESD. In the authors opinion, in selected patients with lesions <15-20 mm, Ki-67 <3% (consider up to 3-20%), without evidence of lymph node metastasis, endoscopic resection should be attempted (with ESD being the preferred technique for lesions >10 mm). CgA level has been shown to be elevated in various diseases, including benign and malignant diseases and associated with acid-suppressive medications ENT#91;21, 22ENT#93;. The specificity of CgA for the diagnosis or prognosis of NETs is compromised by the non oncological and non-NET oncological situations, but is the most common circulating biomarker used for the follow-up of NETs. Tsai et al. ENT#91;23ENT#93; suggested that baseline CgA level is associated with overall survival of gastroenteropancreatic NET (GEP-NET) patients (HR = 13.52, p = 0.045). A 40%or greater increase of change of CgA level may predict tumor progression or recurrence during treatment or surveillance of gastroenteropancreatic NETs. In our study, CgA showed a low sensitivity for detection of recurrence (20%) but a specificity of 79%. The sensitivity was even lower in type I GNET patients (8%). Routine determination of serum CgA in all patients with GNET does not seem to be beneficial. However, it may be helpful in patients with distant disease to assess response to therapy.

This study has some potential limitations. The retrospective nature of our cohort presented limitations mainly in the selection of patients for each therapeutic group and in the collection of patients’ data. Also, this unicenter design can limit the generalizability of findings. Furthermore, an important limitation in our work was that, although a significant number of patients were included, due to the reduced rate of recurrence and mortality of most GNETs, only 3 patients died and 7 patients had metastasis making it difficult to identify prognostic factors.

In conclusion, type I GNET is the most frequent in our series. Identification of risk factors for the presence of metastases and for mortality in these groups of patients can help in individualizing the therapeutic strategy and possibly reducing the burdensome surveillance for patients and hospital endoscopy resources as, even after endoscopic resection, lifelong endoscopic surveillance is required due to the multifocal nature of this tumor. Regardless of disease stage, the overall survival of our patients with type I GNET is excellent. ESD and EMR achieved similar short- and long-term results in this group of patients.